DESIGN CELLS/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

DESIGN CELLS/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

The Rise of Measles

With the recent rise in incidence, oral health professionals should be able to recognize measles and understand the related oral health considerations.

This course was published in the May 2019 issue and expires May 2022. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define measles.

- Identify reasons for the resurgence of measles.

- Discuss prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

- List the role of oral health professionals in curbing the rise in measles cases.

In 1954, John F. Enders, PhD, and Thomas C. Peebles, MD, used blood samples from ill children in Boston to isolate the virus in order to develop a vaccine. The initial vaccine was developed in 1963 and further refined in 1968.1

The current vaccination includes measles and mumps, and is known as measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccination. The recommendations for vaccination against measles include two doses of MMR beginning at 12 months to 15 months. The initial dose provides individuals with a 90% to 95% immunity.2 A secondary dose of MMR is given typically between the ages of 4 and 6.3 With the second dose of MMR, immunity increases to 99.7%.2 With the advent of the measles vaccination, the incidence of the disease decreased such that in 2000, measles was declared eliminated from the US. There were no occurrences of measles for greater than 12 months.1

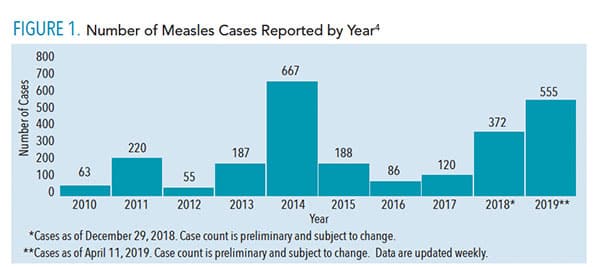

Today, however, this preventable disease is on the rise again. As of April 11, 2019, 555 new cases of measles have been reported (Figure 1).4 States with active cases are California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Texas, and Washington. Outbreaks have been linked with travel to areas where the disease is still endemic such as Europe, Asia/Pacific, and Africa.5,6 Other reasons for the increase include vaccination hesitancy and vaccine refusal.

Oral health professionals may not be familiar with the signs and symptoms of active measles. With the recent rise in incidence, they should be able to recognize measles and understand the related oral health considerations.

Measles virus is transmitted through the respiratory route via coughing and sneezing or direct contact with secretions. Once an individual is infected, clinical signs will appear within 9 days and 19 days.7 Measles can affect individuals of all ages.8 Risk factors for measles virus include children with immunodeficiency such as human immunodeficiency virus, leukemia, or taking corticosteroid’s, travel to areas where measles is endemic, children whose parents declined immunization, and infants who lose passive antibody before the age of routine immunization.8,9 Malnutrition, pregnancy, and vitamin A deficiency are also risk factors for measles.8

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Measles typically begin with a high fever as high as 104°F or more that lasts for 4 day to 7 days. The prodromal phase is also characterized by the classic triad of cough, coryza (head cold, fever, sneezing), and conjunctivitis (red eyes), known as the “3C’s.” Other symptoms may include malaise, anorexia, photophobia, periorbital edema, myalgias, and diarrhea. Adults may experience a transient hepatitis.9

Clinical measles begins with small Koplik’s spots on the buccal mucosa, considered to be pathognomonic for the disease (Figure 2). The lesions can be numerous small, blue-white macules, also referred to as “grains of salt,” surrounded by erythema.9,10 Koplik’s spots occur 1 day to 2 days prior to the characteristic maculopapular skin rash; they may occur on the labial mucosa and soft palate in addition to the buccal mucosa, and in some cases, do not occur at all.10,11 Other oral manifestations associated with measles include candidiasis, necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis, and necrotizing stomatitis if the individual is suffering from severe malnutrition. Pitted enamel hypoplasia of developing permanent teeth may occur in severe cases of measles in early childhood. Enlargement of lingual and pharyngeal tonsils may be found during the course of illness.10

As the disease progresses, the cutaneous rash generally erupts approximately 14 days after exposure to the virus. Erythematous macules and papules begin on the face, head, and neck. Within 48 hours, the lesions coalesce to patches that spread to the trunk and extremities. During this period, patients are most ill. The rash tends to disappear at the location where it first appeared, and fades after 5 days to 7 days.8,9

Individuals who were vaccinated for measles between 1963 and 1967 using the original killed-virus measles vaccine, may have incomplete immunity and are at risk for atypical measles.8,9 During this time, the vaccine was administered to US children who were approximately 1 year. Atypical measles presents with milder symptoms that include prodromal signs and symptoms of fever, headache, abdominal pain, and myalgias, which precedes a rash. The rash begins on the hands and feet and spreads centripetally (moving toward the center). Fortunately, the live-attenuated vaccine replaced the killed vaccine in 1967, and is not associated with atypical measles.8,9

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

The diagnosis of measles is often made through the classic clinical presentation. However, laboratory confirmation can be made through serologic testing using measles specific IgM or IgG titers or viral culture using throat or nasal swabs.8 Prior to the presentation of the rash, measles can mimic other diseases and conditions including influenza, croup, other viral illnesses, and pneumonia. Once the rash develops, other differential diagnoses may include: allergic drug reactions, Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV), infectious mononucleosis, Kawasaki disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, toxic shock syndrome, scarlet fever, fifth disease, rubella (German measles), and varicella (chickenpox).8,9

Because measles is caused by a virus, there is no known cure. Treatment mainly consists of good hydration with fluids, rest, antipyretics, and vitamin A supplementation. In some cases when an individual is markedly febrile, dehydration occurs and intravenous rehydration is required.

Most cases of measles are uncomplicated and resolve in 7 days to 10 days after the onset of illness. Secondary bacterial infections, such as otitis media or pneumonia, will need to be treated with antibiotics. On rare occasions, the virus infects the central nervous system causing encephalitis-related complications. One of the neurologic complications is acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). This disease is characterized by demyelination resulting in ataxia, motor and sensory loss, and mental status changes, and can be fatal.12 Measles inclusion body encephalitis (MIBE) is another neurologic complication. MIBE typically occurs in young infants or immunocompromised individuals who cannot clear the infection. Symptoms include mental status changes, focal seizures, visual or hearing loss 1 year after immunization or acute measles infection, followed by rapid disease progression, coma, and death in many patients.12–14 The third, and more rare type of neurologic complication is subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE). This disease occurs several years after a normal episode of measles and begins with a change of behavior and intellectual decline, progresses to myoclonic seizures, ataxia, and death within 1 year to 3 years. SSPE has been exclusively associated with measles infection and not the vaccine. How it spreads throughout the central nervous system remains unknown.7,15,16

PREVENTION STRATEGIES

In cases where the vaccine cannot be safely administered, such as in pregnant women or immunocompromised patients, travel or exposure to areas where the virus is active should be limited.6 To prevent measles from becoming endemic in the US, the herd immunity threshold must be maintained. Herd immunity threshold refers to the minimum percentage of a community which is immunized against a particular disease in order to prevent an epidemic.17 For measles, the minimum herd immunity threshold must be between 93% and 95% of the population vaccinated.18 In 2015, the National Immunization Survey found that only 72.2% of children between the ages of 19 months and 35 months were fully vaccinated.19 This gap in protection enables the virus to have periodic outbreaks.

VACCINE REFUSAL

Parents may refuse to have their child vaccinated because of medical reasons and nonmedicinal exemptions (NMEs), which encompass vaccine confidence and concern, philosophical objections, and religious barriers.20 Medical reasons for opting out of the vaccination include a severely compromised immune system, anaphylaxis reaction to a previous vaccine component, pregnancy, or a “family history of altered immunocompetence.”21

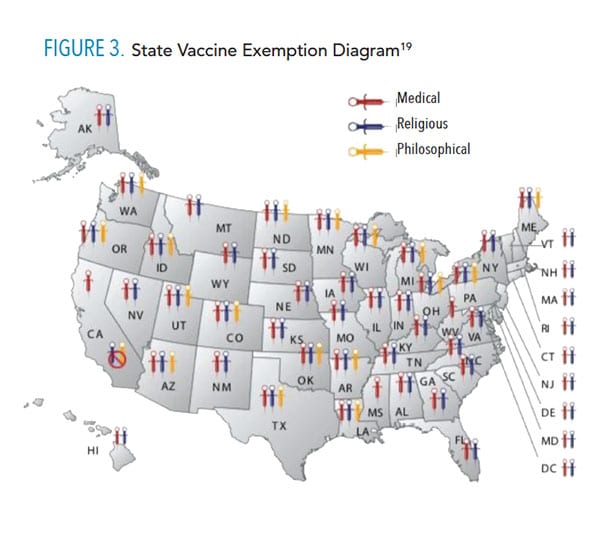

NMEs are on the rise in the US (Figure 3).22 In 2016, there were 18 states that allowed NMEs for vaccination of children prior to registering for school. Olive et al22 analyzed data from these states and discovered that since 2009, 12 of the 18 states demonstrated an upward trend in NMEs. When further examining data at the county level within each state, researchers discovered that several large metropolitan areas have significant numbers of NMEs. These data suggest that if an outbreak occurs in these densely populated areas, measles would be rapidly spread.22

Another important aspect of vaccine hesitancy is the parental beliefs regarding immunizations. Cacciatore et al20 found that a low confidence in the safety or efficacy of immunizations was associated with a greater likelihood of delay or refusal of childhood vaccinations. Social media is often used to spread unfounded beliefs in vaccine safety and efficacy.2 No scientific evidence supports any link between the MMR immunization and autism.2, 23,24 A recent study demonstrates that the MMR vaccination does not increase the risk of autism nor does it trigger autism in susceptible children.24 The study refuted the concern that the MMR vaccination is associated with clustering of autism cases after vaccination.24

A final component to NMEs is family religious or philosophical beliefs. According to Wombwell et al,5 the primary components of the rubella vaccine come from aborted fetal tissue and animal-derived gelatins. Each religious group has its own doctrine when it comes to these components; however, it should be noted that religious beliefs may be a determining factor for acceptance or refusal of vaccinations.

POST-EXPOSURE PRECAUTIONS

Oral health professionals are well suited to support primary prevention. A main line of defense against spreading infectious diseases is assessment of the patient’s medical history. As such, all patients should have a full medical history taken and reviewed at each appointment. Collecting immunization information is also important, as it provides the opportunity to encourage vaccination for prevention of infectious diseases.

For patients who enter the office displaying symptoms of illness, appropriate infection control is paramount. As previously noted, measles is spread via coughing, sneezing, and contact with infectious mucous secretions. For this reason, patient masks should be available in the reception area along with a hand sanitizer dispenser. Furthermore, one of the first presenting symptoms for measles is hyperpyrexia (high fever). Therefore, collecting and assessing vital signs, including temperature, for a symptomatic patient is a critical factor in preventing further transmission of the virus.

Most important, if a patient is displaying signs and symptoms of measles infection, precautions must be implemented. First, oral health care treatment should be deferred, and the patient should be referred immediately to his or her primary physician for diagnosis and treatment.25 Second, as measles is a nationally notifiable disease, oral health professionals need to be well versed in the procedures and protocols used to notify the state Department of Health. The dental office is required to contact the state Department of Health to document the case and to ensure notification is rendered to other potentially exposed patients as measles is a notifiable infectious disease.25 Finally, safeguard the dental team by confirming that dental staff members have updated immunizations to prevent spreading the virus to potentially unvaccinated family members and other patients.25

Once patients with measles are dismissed from the dental office and return home, they, too, need to use precautions. Family members, friends, and school contacts should be advised that measles is highly contagious and infected family members should be isolated. The recommended isolation period is 4 days before to 4 days after the rash manifests.8,9 People who have not been fully vaccinated should receive the vaccine as soon as possible.9

CONCLUSION

Measles is a highly contagious yet preventable infection, which is resurging in the US population. To prevent the spread of measles, oral health professionals need to be familiar with the systemic and oral signs and symptoms of this disease. As a primary line of defense, the dental team must be informed of appropriate prevention and post-exposure precautions. Furthermore, it is the responsibility of the clinician to support and advocate for patient vaccination in order to reduce the prevalence of measles in the US.

REFERENCES

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles History. Available at: cdc.gov/measles/about/history.html. Accessed April 15, 2019.

- DiPaola F, Michael A, Mandel ED. A casualty of the immunization wars: the reemergence of measles. JAAPA. 2012;25:50–54.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles Vaccination. Available at: cdc.gov/measles/vaccination.html. Accessed April 15, 2019.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Number of Measles Cases Reported by Year. Available at: cdc.gov/measles/cases-outbreaks.html. Accessed April 15, 2019.

- Wombwell E, Fangman MT, Yoder AK, Spero DL. Religious barriers to measles vaccination. J Comm Health. 2015;40:597–604.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Traveler’s Health. Available at: cdc.gov/travel. Accessed April 15, 2019.

- Laksono BM, DeVries RD, McQuaid S, et al. Measles virus host invasion and pathogenesis. Viruses. 2016;8:210.

- Chen S, Steele RW. Measles. Available at: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/966220-overview. Accessed April 15, 2019.

- Koenig KL, Alassaf W, Burns MJ. Identify-isolate-inform: A tool for initial detection and management of measles patients in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16:212–219.

- Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Chi AC. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 4th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2016:234–236.

- Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ, Jordan RCK. Oral Pathology: Clinical Pathologic Correlations. 7th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2017:10–11.

- Griffin DE. Measles virus and the nervous system. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;123:577–590.

- Freeman AF, Jacobsohn DA, Shulman ST, et al. A new complication of stem cell transplantation: measles inclusion body encephalitis. Pediatrics. 2004;11:657–660.

- Buchanan R, Bonthius DJ. Measles virus and associated central nervous system sequelae. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2012;19:107–114.

- Rubin E, Reisner HM. Essential of Rubin’s Pathology. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lipplincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014:199–200.

- Ludlow M, McQuaid S, Milner D, et al. Pathological consequences of systemic measles virus infection. J Pathol. 2015:235:253–265.

- Glick M. Vaccine hesitancy and unfalsifiability. J Am Dent Assoc. 2015;146: 491-493.

- World Health Organization. Critical Immunity Thresholds for Measles Elimination. Available at: who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2017/october/2._target_immunity_levels_FUNK.pdf20. Accessed April 15, 2019.

- National Vaccine Information Center. State Vaccine Exemptions. Available at: nvic.org/vaccine-laws/state-vaccine-requirements.aspx. Accessed April 15, 2019.

- Cacciatore MA, Nowak GJ, Evans NJ. It’s complicated: The 2014-2015 US measles outbreak and parents’ vaccination beliefs, confidence, and intentions. Risk Analysis. 2018;38:2178–2192.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Contraindications and Precautions. Available at: cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/general-recs/contraindications.html. Accessed April 15, 2019.

- Olive JK, Hotez PJ, Damania A, Nolan M. The state of the antivaccine movement in the united states: a focused examination of nonmedical exemptions in states and counties. PLOS Medicine. 2018;15:1–10.

- Institute of Medicine. Adverse effects of vaccines: Evidence and Causality. Available at: http://vaccine-safety-training.org/tl_files/vs/pdf/13164.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2019.

- Hviid A, Vinslov Hansen J, Frisch M, Melbye M. Measles, mumps, rubella vaccination and autism: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Mar 5.

- GordonS C, Macdonald NE. Managing measles in dental practice: a forgotten foe makes a comeback. J Am Dent Assoc. 2015;146:558–560.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. May 2019;17(5):26–29.