VADIMGUZHVA/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

VADIMGUZHVA/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Treating Patients with Anorexia Nervosa

Dental hygienists should be prepared to recognize the disorder, provide prompt referral for medical care, and educate patients on protecting their oral health.

This course was published in the May 2019 issue and expires May 2022. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Differentiate the types of eating disorders.

- Identify comorbid mental disorders associated with anorexia nervosa.

- Recognize systemic and oral findings associated with anorexia nervosa.

- List referral sources for eating disorder treatment.

Eating disorders are categorized as any psychological disorder that impairs psychosocial functioning and physiological health.1 Eating disorders have the highest mortality rate among mental illnesses and are complicated, multifactorial diseases controlled by social, familial, and biologic factors.2,3 Research indicates that biological factors, such as genetics, may increase the risk of eating disorders.4–6 A pattern of genetic inheritance has been found in mental illnesses, such as anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorders, all of which are commonly found in those with anorexia nervosa.4–7 Symptoms associated with generalized anxiety have been identified as risk factors for developing eating disorders.8 Environmental risk factors that trigger the onset of eating disorders are: bullying, low self-esteem, stress, pressure to achieve, cultural preference for body shape, and media-driven thin body images.2,5,6 Individuals with an eating disorder have different triggers, thus some eating disorders may manifest differently than others.5,6

Anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorders are common.2 This article will focus on anorexia nervosa, as it is the most frequently diagnosed eating disorder in the United States.

TYPES OF EATING DISORDERS

Those with bulimia nervosa engage in frequent periods of binge eating followed by purging of the food through laxatives, enemas, and/or self-induced vomiting. A nonpurging form occurs when individuals binge eat followed by compensation such as fasting or excessive exercise.2,9 In 2013, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)—the manual used by US health professionals that serves as the gold standard in the diagnosis of mental disorders—recognized binge-eating disorder. It differs from bulimia nervosa in that the individual consumes a large amount of food in a short time, but does not partake in compensatory behaviors to prevent weight gain.9

Other types of eating disorders include pica, rumination, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, and diabulimia.9 Pica, found in patients older than age 2, is characterized by the consumption of nonnutritive food for more than a month. Clay, starch, dirt, soap, or paper products are examples of what individuals with pica may consume.9

Rumination is a disorder in which individuals eat food, regurgitate the partially digested product, and then rechew or swallow the regurgitated material. This problem must take place for at least 1 month before an official diagnosis can be made.2,9

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder is defined as the avoidance or restriction of food intake due to the dislike of food taste without the emotional factors such as fear of being fat or gaining weight.9

Diabulimia is a deliberate insulin underuse in people with type 1 diabetes for controlling weight.3,10 About 38% of those with type 1 diabetes are believed to have an eating disorder.10

ANOREXIA NERVOSA

A mental illness, anorexia nervosa is characterized by a distorted body image and a fear of being overweight.11,12 Individuals typically present below 15% of their optimal body mass index (BMI); however, a person may have the disorder without looking emaciated.4,11,12 Studies have found that large-bodied individuals also experience the disorder.12 The disease is characterized by individuals starving themselves through exercise, laxatives, or vomiting.2,4,11–13

Anorexia nervosa has two clinical subtypes: food restricting and purging.13 The food-restricting category makes up 50% of all anorexia cases.13 These individuals will consume between 300 calories and 500 calories a day with a focus on zero to few grams of fat.13 Patients under the purging subtype follow rigorous dieting coupled with cycles of purging unwanted calories through self-induced vomiting, diuretics, laxatives, and/or exercise.3,13 Between 40% and 80% of patients with anorexia use excessive exercise to avoid weight gain.10

Those with anorexia usually experience low self-esteem, intense desire to fit in, or fear of social acceptance.13,14 Rituals over food preparation, ways to eat their food, and excessive talk about food are common among these patients. 4,11,12,15 The onset of the disorder is normally between the ages of 13 and 20, and it affects women more than men.4,16 Approximately 0.9% of American women and 0.3% of American men have the disorder.3,6 However, a new study indicated 13% of women older than 50 show signs of the disease.17 Childhood obsessive-compulsive traits and anxiety symptoms—such as strong-willed affects, competitive natures, strict rule following, and perfectionism—often precede the disorder.8,10,14 These characteristics fuel the disorder because the individual is capable of starving his or herself while ignoring and persevering through the physical symptoms of malnourishment.9,11,12,16

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis of anorexia nervosa is based on patients’ weight for their age, denial of having a low weight, refusal to maintain normal body weight, amenorrhea, and use of psychological self-report screening tools.4,9,11,16 Commonly used screening tests are: Eating Attitudes Test, Eating Disorder Inventory, Eating Disorder Screen for Primary Care, and the SCOFF questionnaire (Do you make yourself Sick because you feel uncomfortably full? Do you worry that you have lost Control over how much you eat? Have you recently lost more than One stone, or 14 lbs in a 3-month period? Do you think you are too Fat, even though others say you are too thin? Would you say that Food dominates your life?16

Some individuals with anorexia can see themselves as thin, and the thinner they perceive themselves, often the stronger the disease. However, others can be unaware of their physical thinness, and have a perpetual fear of becoming overweight.11–13 Those with anorexia believe that their body weight, shape, and size are directly related to their self-worth and self-esteem.11 Feelings of isolation, depression, and distorted thoughts are common.7,12–14

Health history and risk factors can aid in the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa. In the past, research focused on parenting styles and family dynamics as the contributing factors. Although the interaction between parent and child can contribute to these individuals seeking control, parenting is no longer the sole risk factor.5

Often environmental factors initiate the onset of the disorder.5,18 The socialization of thinness is the best known environmental contributing factor.10,14 Research demonstrates that 40% to 60% of girls ages 6 to 12 are concerned with their weight and have a fear of being fat.10 Social media has led to an increase in the perception of thinness as the accepted body image. The increased amount of time that adolescents spend on social media has given way to unrealistic messages, negative comments on body images, and false portrayal of happiness, while promoting conformity to social scenes.10 Also, weight bullying and weight stigma during school contribute to low self-esteem and body dissatisfaction.10

In anorexia nervosa, genetics has a 50% to 80% chance of playing a contributing role.2–4,16 Additionally, studies now show more than half of individuals with anorexia nervosa have co-occurring disorders, including anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder, depression, social phobia, and post-traumatic stress syndrome.3,8,10 Two-thirds of people with anorexia nervosa show signs of anxiety before the onset of the eating disorder.8,10 Individuals with anorexia have irrational thoughts about their health, appearance, and loved ones, and often become controlled by their thoughts, causing them to become secretive, withdrawn, over-sensitive, irritable, and defensive.2,4,12,13

Isolation among those with anorexia is common due to avoidance of social events that may include food and competitive feelings about weight and dietary habits.12,13,16

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Oral health professionals should be able to recognize the signs of the anorexia nervosa in order to help patients seek help (Table 1). The medical history provides a great deal of relevant information. A BMI score ≤ 17 is considered mild, 16 to 16.99 is moderate, 15 to 15.99 is severe, and < 15 is extreme.11 As cardiovascular damage is relatively common among this patient population, hypotension with marked orthostatic changes, bradycardia, and cardiac arrhythmias are common signs of the disorder.1,4,13,18 Further findings on the medical history could be fatigue, light-headedness, cold intolerance, sleep apnea, constipation, irregular periods, or amenorrhea.1,12,16

Slowed digestion leads to stomach pain, vomiting, fluctuations in blood sugar, feeling full after eating small amounts of food, and bacterial infections.13,16,18 Additionally, the brain will begin showing signs of caloric deprivation, such as difficulty concentrating and obsessive thoughts, commonly around food.1,13,16,19 Peripheral nerve damage, including numbness and tingling in hands, feet, and other extremities, is a sign.13,19 Patients have an increased risk for seizures and muscle cramps due to electrolyte imbalance.13 Individuals may experience syncope and vertigo upon standing because the blood vessels are unable to push enough blood to the brain.13

Signs of anorexia may be visible during extra- and intraoral exams. The skin often appears thin, dry, blotchy, or yellow.4,15,16 Fine hair, known as lanugo, may be growing throughout the body. Thinning of the hair and brittle nails may be evident.4,16,19–21 The eyes appear sunken in with dark shadows and the appearance of dehydration is evident.4,15,16,19,20

Intraorally, the findings may be salivary gland enlargement known as sialdenosis, particularly the parotid gland; dry/cracked lips; burning tongue syndrome; atrophic mucosa; and dental enamel erosion.4,16,20–22 Temporomandibular disorder symptoms, such as dizziness, headache, facial pain, jaw tiredness, tongue thrusting, and a lump feeling in the throat, have been reported.21,23 Vitamin C deficiency may contribute to gingivitis and poor wound healing.12,21 Oral mucosa in patients with anorexia nervosa show signs of both local and systemic factors, such as petechia on the palate, an orange-yellow palate discoloration, and excoriations from cheek and lip biting, and labial erythema.20,21 Labial erythema in a red linear pattern can be found on the vermillion border of the lips and often occurs with exfoliative cheilitis.20 The thinner mucosa allows the visualization of connective tissue, hence the orange-yellow coloration.20 The discoloration is due to carotenemia in increased level of serum carotene. Figure 1 and Figure 2 illustrate some of the oral signs of anorexia nervosa.4,20

exfoliative cheilitis (B); and orange-yellow pigmentation on the soft palate (C). Reprinted from: Panico R, Piemonte E, Lazos J, Gilligan G, Zampini A, Lanfranchi H. Oral mucosal lesions in anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and EDNOS. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;96:178–182. Copyright 2019, with permission from Elsevier.

ORAL HEALTH INDICATIONS

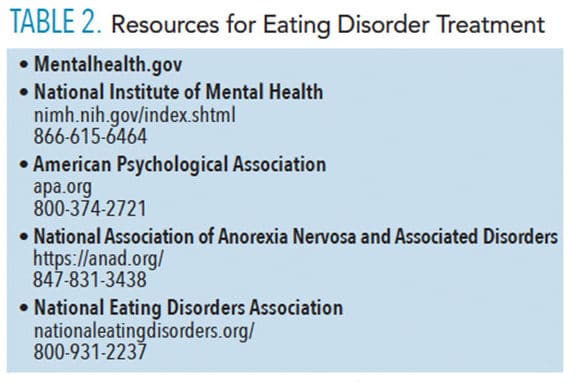

If an eating disorder is suspected, referral to an eating disorder specialist is recommended. Patients who demonstrate physiologic concerns should be immediately referred to a medical provider. 2,4,19–21 Table 2 features resources for eating disorder treatment.

Patients who disclose eating disorders should be educated on how to care for their teeth to prevent dental caries. The depleted serum calcium levels can cause reduced buffering capacity of the saliva, increasing caries risk.22 Patients who use vomiting as their purging method should use products to reduce the effects of acid erosion. In addition, power toothbrushes and mouthrinse can help reduce gingivitis. Patients with anorexia may be taking medications, such as cyproheptadine, clozapine, risperidone, amitriptyline, fluoxetine, clonazepam, and topiramate.4 Many of these cause xerostomia, orthostatic hypotension, gingival soreness, and abnormal taste, so oral health professionals should be aware of these side effects. If extraoral symptoms, such as orthostatic hypertension, are present, the patient should sit up slowly and wait 3 minutes to 5 minutes before standing.

TREATMENT

Treatment of any eating disorder is complex and multifaceted.4 Typically, individuals will have a team of professionals to treat the eating disorder that may include a nutritionist, psychiatrist, psychotherapist, and behavior therapist.15 Pharmacotherapy may be used as an adjunct to cognitive behavior therapies.1 The first step is to persuade the patient and family members that treatment is necessary.2,4 Varying levels of care are available, such as inpatient hospitalization, residential care, partial hospitalization, intensive outpatient, or outpatient treatment. Patients with physical symptoms such as depressed vital signs, laboratory findings presenting acute risk, weight that falls below 25% of an ideal body weight, or suicidal thoughts need inpatient hospitalization.2,24

In residential treatment, patients receive 24-hour care, but their medical treatment is less intense and they are given more autonomy with less psychiatric monitoring.2,24 Medically stable patients who need weight restoration with daily assessment of physiologic and mental status, engage daily with purging behaviors, and consistently limit caloric intake require partial hospitalization.4,24 Outpatient treatment is recommended for patients who are medically and psychiatrically stable and do not need daily medical monitoring, but still require weight restoration and behavioral management support.2,4,24

Treatment can be successful; however, only about one-third of people receive treatment.6 Approximately 45% of patients who receive treatment for anorexia have positive outcomes.4 Between 5% and 10% of patients die of complications associated with the eating disorder, such as starvation, electrolyte imbalance, and cardiac arrest.1,2,4,6

CONCLUSIONS

Oral health professionals may encounter individuals who exhibit extra- and intraoral signs and symptoms of anorexia nervosa. Dental hygienists should be prepared to recognize the disorder, provide prompt referral to medical care, and educate patients on protecting their oral health. All of these actions can improve the overall health of the patient and potentially save his or her life.

REFERENCES

- Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson J, Loscalzo J. eds. Eating disorders. Harrison’s Manual of Medicine. 19th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2016.

- Stewart Agras W. Disorders of eating: anorexia, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. In: Shader RI, ed. Manual of Psychiatric Therapeutics. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: 2003:94-102.

- National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders. Eating Disorder Statistics. Available at: https://anad.org/education-and-awareness/about-eating-disorders/eating-disorders-statistics/. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Gwirtsman HE, Mitchell JE, Ebert MH. Eating disorders. In: Ebert MH, Leckman JF, Petrakis IL. eds. Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Psychiatry. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2019.

- National Eating Disorder Association. Busting the myths about eating disorders. Available at: nationaleatingdisorders.org/busting-myths-about-eating-disorders. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Eating Disorders Coalition. Facts about eating disorders: what the research shows. Available at: http://eatingdisorderscoalition.org.s208556.gridserver.com/couch/uploads/file/fact-sheet_2016.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- National Eating Disorder Association. Anxiety, Depression, and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Available at: nationaleatingdisorders.org/anxiety-depression-obsessive-compulsive-disorder. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Schaumberg K, Zerwas S, Goodman E, Yilmaz Z, Bulik CM, Micali N. Anxiety disorder symptoms at age 10 predict eating disorder symptoms and diagnosis in adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018 Oct 24.

- Reus VI. Psychiatric disorders. In: Jameson J, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Loscalzo J, eds. In: Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 20th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2018.

- National Eating Disorder Association. Statistics and Research on Eating Disorders. Available at: nationaleatingdisorders.org/statistics-research-eating-disorders. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Bressert S. Anorexia nervosa symptoms. Available at: psychcentral.com/disorders/eating-disorders/anorexia-nervosa-symptoms/. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- National Eating Disorder Association. Anorexia nervosa. Available at: nationaleatingdisorders.org/learn/by-eating-disorder/anorexia. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, Pataki CS, Sussman N. Feeding and eating disorders. In: Kaplan & Saddock Synopsis of Psychiatry Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry. 11th ed. New York: Wolters Kluwer; 2013:509–516.

- Culbert KM, Racine SE, Klump KL. Research review: What we have learned about the causes of eating disorders- a synthesis of sociocultural, psychological, and biological research. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56:1141–1164.

- Williams PM, Goodie JL. Anorexia nervosa. In Domino F, ed. The 5-minute Clinical Consult. 2012 20th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012:78–79.

- Office on Women’s Health in the Department of Health and Human Services. Anorexia nervosa. Available at: womenshealth.gov. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Gagne DA, Von Holle A, Brownley KA, et al. Eating disorder symptoms and weight and shape concerns in a large web–based convenience sample of women ages 50 and above: results of the gender and body image (GABI) study. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:832–844.

- Franko DL, Tabri N, Keshaviah A, et al. Predictors of long-term recovery in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: Data from a 22-year longitudinal study. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;96:183–188.

- National Eating Disorder Association. Health Consequences. Available at: nationaleatingdisorders.org/health-consequences. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Panico R, Piemonte E, Lazos J, Gilligan G, Zampini A, Lanfranchi H. Oral mucosal lesions inanorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and EDNOS. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;96:178–182.

- Romanos G, Javed F, Romanos E, Williams R. Oro-facial manifestations in patients with eating disorders. Appetite. 2012;59:499–504.

- Patel N, Milward M. The Oral Implications of Mental Health Disorders Part 1: eating disorders. Dental Update. 2019;46:49–52.

- Souza SP, Antequerdds R, Aratangy EW, Siqueira SRDT, Cordás TA, Siqueira JTT. Pain and temporomandibular disorders in patients with eating disorders. Brazilian Oral Res. 2018;32: e51.

- National Eating Disorder Association. Types of Treatment. Available at: nationaleatingdisorders.org/treatment. Accessed April 17, 2019.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. May 2019;17(5):30–33.