Baby Boomers and the Rise of STDs

Educate your older adult patients about the risks of contracting sexually transmitted diseases.

This course was published in the October 2011 issue and expires October 2014. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the oral implications of sexually transmitted diseases among baby boomers.

- Explain the oral symptoms of gonorrhea, syphilis, human papillomavirus, and herpes simplex virus.

- Detail the role of dental professionals in the education of patients at risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases.

For sexually active baby boomers, the fear of pregnancy has faded, but the risk of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) is real. Baby boomers were adolescents and young adults during the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s where sexual inhibitions were relaxed and experimentation was widespread.1 Today, many traditional social/moral barriers have disappeared and casual liaisons have become more accepted. As a result, a growing percentage of the nation’s 76 million baby boomers,2 especially those without partners, are engaging in risky sexual behavior.

STDs are the most common communicable diseases in the United States, yet STD data collection efforts are focused on people younger than 35. This needs to change. Older adults are engaging in sexual activity. For example, a study by the National Council on Aging revealed that 48% of 60-year-olds were sexually active and engaging in high-risk sexual activities, often assisted by erectile dysfunction medications.3

AGE IS JUST A NUMBER

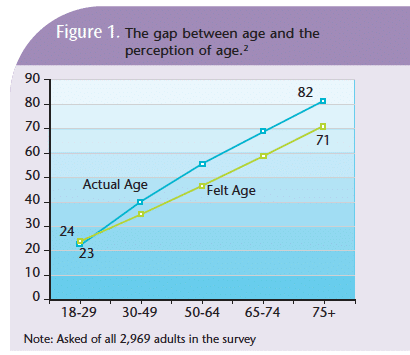

Older adults today typically feel better and have more energy than generations past. They are working longer, living longer, and remaining sexually active longer. According to a Pew Research Center report, nearly half of those surveyed who were 50 years or older said they felt at least 10 years younger than their chronological age. Among respondents age 65 to 74, one-third noted they felt 10 years to 19 years younger than their age, and one out of six reported feeling at least 20 years younger than their actual age (Figure 1).2

Changes in age perception, increased divorce rates, and improved erectile dysfunction treatments have increased the vulnerability of older adults to STDs. As the number of sexual partners increases, so does the risk of contracting STDs, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), gonorrhea, syphilis, human papillomavirus (HPV), and herpes simplex virus (HSV).4 The contraction of one STD also increases the risk of subsequent HIV infection.5

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS INFECTION

Baby boomers are at greater risk of contracting HIV than they may realize.6 Chiao, Ries, and Sande found that sexual contact is HIV’s most likely transmission route among older adults.7 The use of condoms among older adults, once the accepted means of protection for boomers, is decreasing. Recent data reveal that 83% of sexually active older adults never use condoms, and health professionals seldom counsel boomers about STD risks and prevention strategies.3 As a result, the numbers of late or missed diagnoses of HIV in people older than 50 is rising, and treatment outcomes are poor.7

ORAL IMPLICATIONS

STDs are most commonly transmitted to the oral cavity through oral sex, which is increasingly popular because many view it as a safer option than intercourse.8 Dental hygienists should routinely perform thorough intraoral and extraoral examinations, including the head and neck with lymph node palpation. Patients who present with symptoms of disease in the head, neck, or oropharyngeal regions should be referred to a specialist for immediate medical follow-up.

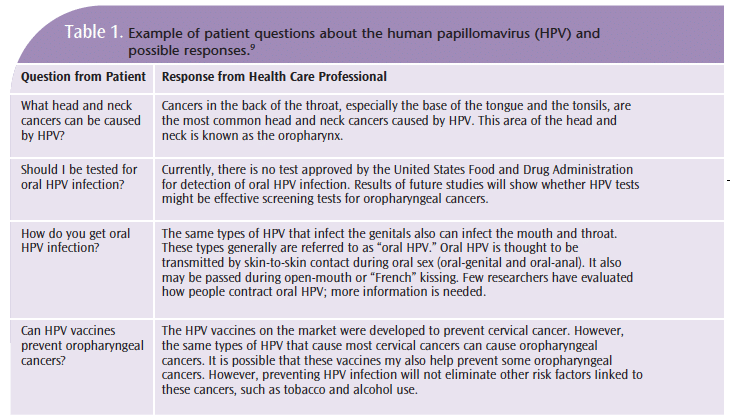

According to a meta-analysis recently published by the American Dental Association, traditional visual and tactile screening examinations are less effective in identifying oropharyngeal cancers because the area is not easily viewed.9 Consequently, oropharyngeal cancers are more likely to be detected at later stages.9 Although dental hygienists may not think of STD education as part of their skill set, as prevention specialists, they are well suited to advise patients about these risks (Table 1).

SYMPTOMS

Oral components of bacterial and viral sexually transmitted diseases are more difficult to diagnose and treat than genital symptoms. Often, oral STDs remain asymptomatic while the genital component is symptomatic. When oral symptoms are present, dental professionals must strongly encourage patients to seek medical attention.

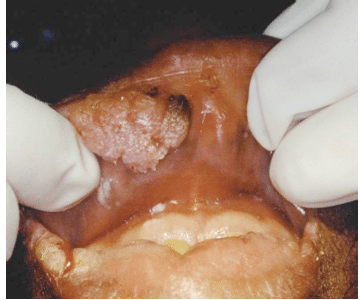

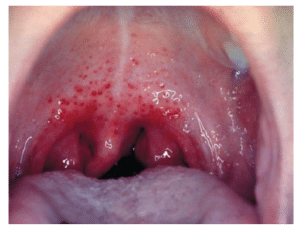

Gonorrhea and syphilis can present as oral bacterial infections. Patients with oral gonorrheal infections may experience gingival swelling, mouth sores, discharge, and bleeding, in addition to sore throat and flulike symptoms (Figure 2). Gonorrhea is often asymptomatic genitally but oral symptoms may be present.10

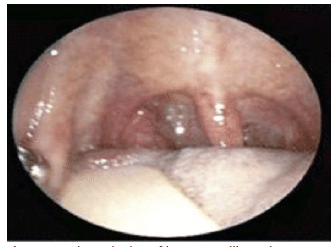

positive squamous cell carcinoma of the palatine tonsil.

Courtesy of Susan Muller, MD, DMD, Winship Cancer

Institute, Emory University, School of Medicine, Atlanta

The symptoms of oral syphilis are often indistinguishable from other diseases. The patient may present with mouth and facial sores that occur at all stages of the disease. Referral to a primary care physician or specialist is very important.

Active bacterial STDs can be transmitted from patient to practitioner, further emphasizing the need for strict adherence to established infection control protocols.

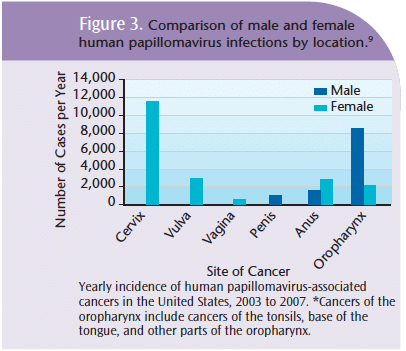

HPV and HSV are viral infections that have the greatest implications for the oral cavity. HPV, the primary cause of cervical cancer, has been implicated in oropharyngeal, throat, head, and neck cancers.11 The number of diagnosed HPVrelated cancers has significantly increased over the past 30 years (Figure 3).9 The risk of contracting HPV also increases with age.

HPV-related mucosal lesions appear in the oral cavity, nasal passages, esophagus, and larynx.12 These lesions may appear white or the same color as surrounding tissues, typically have a bumpy surface, and are usually smaller than 1 centimeter. Figure 4 through Figure 7 provide examples of HPV-related lesions. These lesions require biopsy and histologic/ pathologic examination.13-16 (For a comprehensive review of identifying HPV-related lesions, read “The Dental Hygienist’s Role in HPV Recognition” from June 2010).

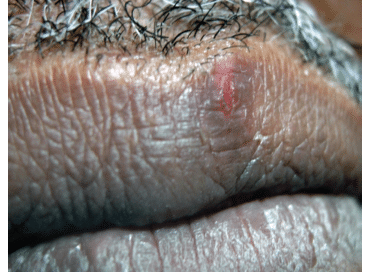

HSV-1 generally causes oral infections (Figure 8 and Figure 9) and HSV-2 causes genital infections, but they can occur in both places. These viruses are most contagious during active outbreaks, and are often spread through viral shedding when there are no recognizable symptoms. People with recurrent oral HSV-1 outbreaks shed the virus in their saliva about 5% of the time, even without symptoms.17 By the time Americans reach young adulthood, 50% have HSV antibodies, while 80% to 90% of Americans older than 50 contain HSV antibodies.17 Oral HSV-2, although rare, may go unnoticed or mistaken for oral HSV-1 because it presents with similar symptoms but fewer outbreaks.17

Because all types of HSV can be transmitted through contact during outbreaks, clinicians should take the necessary infection control precautions. Patients experiencing HSV outbreaks should be encouraged to reschedule elective appointments.

DENTAL HYGIENE CARE

Because dental hygienists are often the first clinicians encountered during routine dental visits, proficiency in intraoral and extraoral examination is a critical assessment skill. Patient education, preventive care, and clinical evaluation complete the dental hygiene process of care.

All members of the dental team should remain up-to-date about the relationship between STDs and the oral cavity, as well as the symptoms of these diseases. Risk assessment of older adults should also include STD screening.

All patients with STD symptoms should be referred for further evaluation. A multidisciplinary approach, including input from physicians, nurses, pharmacists, dietitians, health educators, social service professionals, and mental health providers, ensures that patient needs will be met. The most important member of the multidisciplinary team is the patient, and he or she should be encouraged to participate in the development of appropriate treatment strategies.

Older adults tend to have more established beliefs and may be in denial about the risk of acquiring STDs. Because some health care professionals are reluctant to discuss sexuality with their older patients, this important aspect of health may never be addressed. Fortunately, the paradigm is shifting toward a more realistic view of aging that supports sexuality among older adults.

The dental team can play an important role in increasing patients’ knowledge about STDs and sexual behavior, as well as their associated risks. This process is assisted by developing a good patient/provider relationship and an environment that supports education. Raising awareness of these issues is important, and oral health professionals can make a significant difference by taking this educational opportunity out of the dental office and into the community-at-large.

REFERENCES

- Malhotra S. Impact of the sexual revolution: consequences of risky sexual behaviors. Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons. 2008;13(3):88-90.

- Pew Research Center. Growing Old in America: Expectations vs Reality. Available at: http://pewsocialtrends.org/2009/06/29/growingold-in-america-expectations-vs-reality. Accessed September 26, 2011.

- High KP, Calvet HM. Sexually transmitted diseases other than human immunodeficiency virus infection in older adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:609-614

- Gouveia-Oliveira R, Pedersen AG. Higher variability in the number of sexual partners in males can contribute to a higher prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in females. J Theor Biol. 2009;261:100-106.

- Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect. 1999;75:3-17.

- Kearney F, Moore AR, Donegan CF, Lambert J. The ageing of HIV: implication for geriatric medicine. Age Ageing. 2010;39:536-541.

- Chiao EY, Ries KM, Sande MA. AIDS and the elderly. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:740-745.

- Edwards S, Carne C. Oral sex and the transmission of viral STIs. Sex Transm Infect. 1998;74:6-10.

- Cleveland JL, Junger ML, Saraiya M, et al. The connection between human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas in the United States Implications for dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142:915-924.

- Barlow D. The diagnosis of oropharyngeal gonorrhoea. Genitourin Med. 1997;73:16-17.

- Psyrri A, Cohen E. Oropharyngeal cancer: clinical implications of the HPV connection. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:997-999.

- Cutsem EV, Snoeck R, Van Ranst M, Fiten P, et al. Successful treatment of a squamous papilloma of the hypopharynx- esophagus b local injections of (S)-1-(3-hydroxy-2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl) cytosine. J Med Virology. 2002;45:230-235.

- Sapp PJ, Eversole, LR, Wysocki GP. In: Rudolph P, ed. Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2004:165-166,223-224.

- Eversole LR. Papillary lesions of the oral cavity: relationship to human papillomaviruses. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2000;28:922-927.

- Lukes SM, Meneses MB. The dental hygienist’s role in HPV recognition. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2010;8:72-77.

- Gillison ML, Koch WM, Shah KV. Human papillomavirus in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: are some head and neck cancers a sexually transmitted disease? Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11:19-199.

- Xu F, Sternberg MR, Kottiri BJ, et al. Trends in herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 seroprevalence in the United States. JAMA. 2006;23;296:964-973.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. October 2011; 9(10): 50-53.