Unlocking the Forensic Power of Dental Records

Comprehensive dental recordkeeping not only enhances patient care but also plays a pivotal role in forensic odontology, aiding in the identification of deceased individuals and supporting medicolegal investigations.

This course was published in the October 2023 issue and expires October 2026. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 145

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Explain the importance of accurate antemortem dental records.

- Summarize pertinent contents of a complete dental record.

- Discuss the procedures and benefits of conducting dental record audits.

Dental records include information on a patient’s diagnosis, status, treatment plan, and any communication made between the dental practice and the patient.1 Dental recordkeeping is a daily task for oral health professionals and should comprehensively reflect every decision, finding, diagnosis, occurrence, and rendering of services for each patient encounter.2,3

Effective recordkeeping serves the patient throughout the lifespan as the basis for continuity of care, medicolegal concerns, and forensic investigations.1,4-6 Minimum legal requirements and specifications regarding proper management for dental recordkeeping are established by individual states and should continually be consulted by oral health professionals.1,7 However, additional guidelines and recommendations from organizations, such as the American Dental Association (ADA), American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA), American Board of Forensic Odontology (ABFO), and International Criminal Police Organization (Interpol), should also be used as criteria to evaluate the quality of dental records.

Applying Forensics to Dental Records

A sound understanding of how dental records are used and the role they serve as a communication tool or as evidence can help prevent errors and the creation of incomplete records.1,8,9 While thorough dental recordkeeping practices are the best defense in accusations of malpractice, quality dental records are also used in human identification of unknown deceased persons and physical abuse cases.6,10-12

Documentation of patient data collected over time becomes part of a patient’s antemortem (AM) before-death dental record and is used by forensic odontologists when identifying human remains. Because the record can demonstrate that individual’s uniqueness, it may be requested by law enforcement in the event that the person becomes missing and is then found or presumed deceased.13,14 Such circumstances may present as isolated occurrences or could be part of a mass fatality incident involving tens, hundreds, or thousands of deceased individuals who are otherwise not recognizable due to trauma or decomposition, or not able to be distinguished from others due to commingling. In these cases, the dental record may be one of the only viable sources to provide information for the purpose of human identification.

Following explosions or fires, incinerated human remains may yield very little biometric information regarding the individual’s identity beyond postmortem (PM), or after-death dental evidence. Retrieved forensic dental evidence is compiled into a PM forensic software with search capabilities compatible with missing persons databases.6,13 However, for software search commands and reconciliation efforts to yield results, information from an accurate and complete AM dental record is critical.6,15 Therefore, the knowledge and commitment for sound AM dental recordkeeping is an ethical responsibility for oral health professionals.

If fingerprints and DNA retrieval are not feasible, then a forensic odontological investigation becomes crucial for reconciling human remains. During an investigation, law enforcement may contact the decedent’s dental home for record retrieval. This administrative request does not require a warrant, court order, or subpoena and the dentist of record is protected under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act 45CFR 164.512 to release the information without the patient’s authorization, or consent from next of kin or a guardian.1,7,16

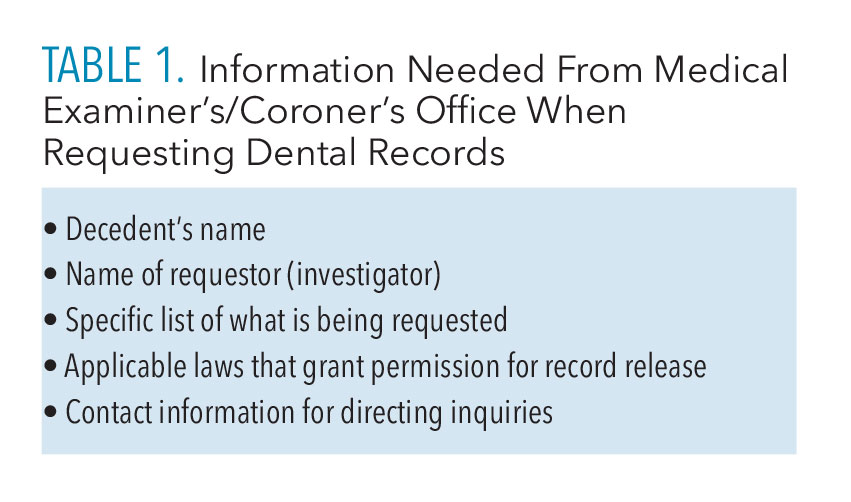

Table 1 lists the typical information included within a notice of records request from a medical examiner’s/coroner’s office. Upon release, copies of the dental record should be made and retained by the dental provider while original dental records should be released to authorities. The dental office should obtain and keep a receipt to show that the record was released to authorities.1

Table 1 lists the typical information included within a notice of records request from a medical examiner’s/coroner’s office. Upon release, copies of the dental record should be made and retained by the dental provider while original dental records should be released to authorities. The dental office should obtain and keep a receipt to show that the record was released to authorities.1

Record retention timelines required for dental records are set by state laws and can vary. Currently, several states do not have record retention standards. The ADA’s guidelines stipulate the retention of records for 7 years from the date of last entry.1,17

Proper disposal of dental records at the end of the required retention timeline is acceptable, however, if unable to retrieve a record due to disposal, then a decades-old cold case would not be able to rely on forensic odontology. Therefore, the American Society of Forensic Odontology recommends that dental records should be preserved by the dental office for an extended duration, surpassing the state’s mandated retention period whenever feasible.18

Once retrieved by authorities, the dental record should provide detailed information regarding unique identifying characteristics to facilitate comparison against PM data so that identity reconciliation is feasible. Dental records should be able to be clearly understood by any healthcare professional, including forensic odontologists.1 Dental records can determine a person’s identity efficiently and cost-effectively.

Contents of a Complete Dental Record

Forensic odontology investigations hinge on three elements. First, there must be quality AM data to retrieve.14,19 Second, there must be dental data from the unidentified person. Third, these two types of data must allow for scientific comparisons against one another so that an opinion report of the person’s identity can be made by a forensic odontologist, and the identity can be legally established with the state’s vital records office by a medical examiner or coroner.6,9,19 From there, a death certificate can be issued and the body released to the family for final arrangements and management of affairs.

According to Stow and Higgins,5 a lack of dental data may be due to incomplete charting, missing or inadequate images, or limited information on unique and distinguishing features. Guidelines and standards of the ADA, ADHA, ABFO, and Interpol provide a wealth of information regarding best practices for dental recordkeeping and are readily available online for easy access by dental offices.1,2,6,20

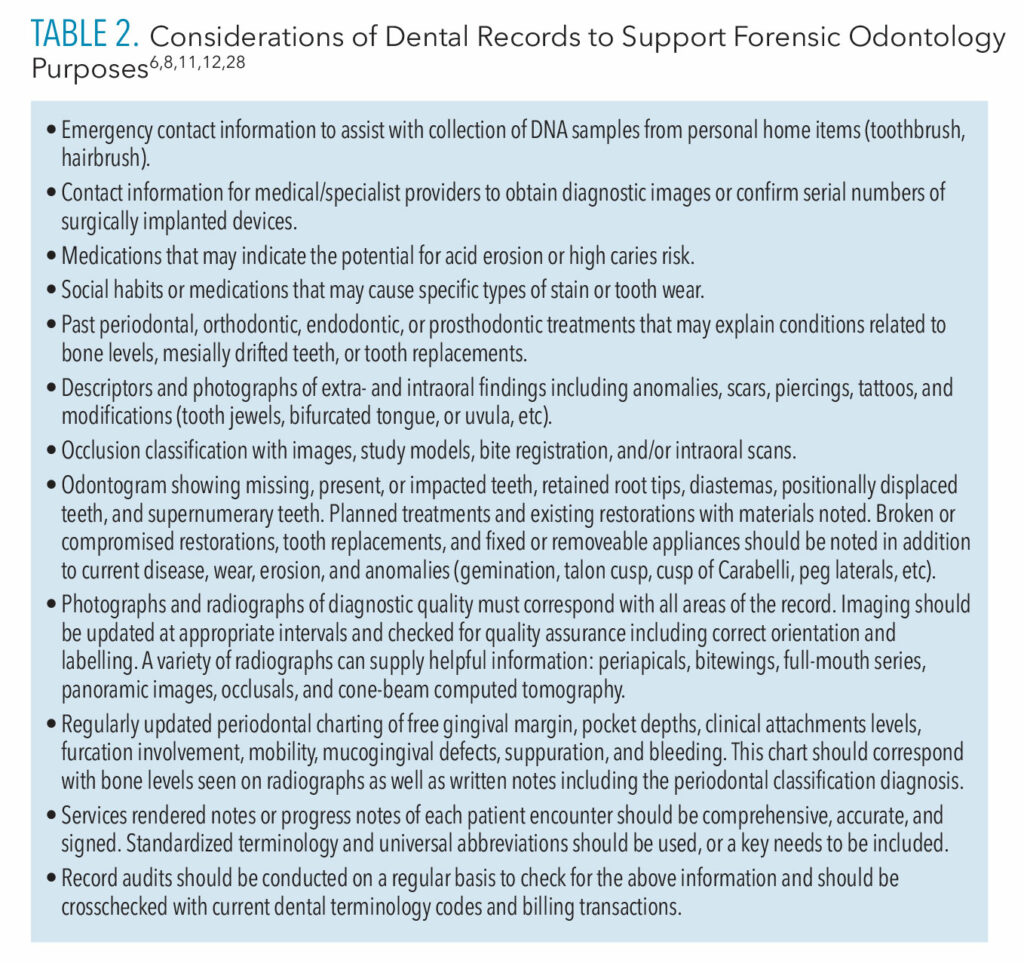

The contents of a comprehensive record include data related to the medical/dental histories, social history, assessments of extra- and intraoral structures, occlusion, dental charting (odontogram), periodontal charting, services rendered/progress notes, and correspondences. Table 2 lists several items related to the parts of a dental record along with some special considerations for characteristics that might not always be part of a record but could be useful.

The contents of a comprehensive record include data related to the medical/dental histories, social history, assessments of extra- and intraoral structures, occlusion, dental charting (odontogram), periodontal charting, services rendered/progress notes, and correspondences. Table 2 lists several items related to the parts of a dental record along with some special considerations for characteristics that might not always be part of a record but could be useful.

The overall quality of dental recordkeeping tends to be inadequate.8,11,21,19,22-27 For example, studies of dental record audits or quality assurance have reported the following: inability to locate or retrieve requested records, incomplete or insufficient information for certain criteria, poor quality radiographs or no radiographs, not up-to-date, and incomplete or no dental odontogram.8,22–27

In a survey of American and Canadian forensic odontologists, 69% reported suspected fraud or negligence among reviewed dental records during their careers, which could negatively impact forensic investigations.14,28 Additionally, surveyed oral health providers have been found to overestimate their recordkeeping skills when compared to ADA guidelines or criteria regarded as valuable for forensic odontology.23,28

Dental Record Audits

Conducting a systematic audit of records is key to ensuring best practices.29,30 An audit will help determine whether practiced clinical activities meet the minimum requirements for state laws and are aligned with industry standards.1,2,6,7,20 An internal audit system can also help support quality assurance, safety, and patient outcomes by revealing deficiencies.

On a monthly, quarterly, or annual basis, randomly chosen patient records representative of the care provided by each clinician in the practice from a certain time period should be selected for inclusion in the audit.29–31 All clinicians should be trained on the audit process, then assigned to participate as reviewers. Team members, however, should not be assigned to review a patient record that they completed.

Reviewers should use a checklist of industry criteria to assess the accuracy and completeness of each selected record to help answer the following questions:

- Are contents of the record up-to-date?

- Do the dental and periodontal charts match what is seen on the radiographs and intraoral images?

- Are the radiographs of diagnostic quality and correctly labeled, mounted, and located within the correct record?

- Are treatment plans correct and appropriate according to standards of care?

- Are the services rendered/progress notes correct, free of typos/misspellings, and do they use accepted abbreviations?

- Can the patient’s study models or three-dimensional images be located within the office?

Upon identification of inaccuracies or deficiencies, an agreed upon action plan for corrections should be devised and implemented.29 By answering these questions, re-occurring errors will be identified and protocols can be implemented to help avoid repeating mistakes.31

To initiate an internal audit system, a lead coordinator should be selected from the clinical staff.29 The coordinator may implement an audit based on a cyclic schedule or an identified issue related to recordkeeping practices.31 The coordinator can manage record selection and assignments, as well as distribution of the audit form and referenced industry standards/criteria for evaluation purposes. Once established deadlines for audit completion and corrections have passed, the coordinator should follow up on any that are still in progress.

Findings from all audits should be compiled and blinded so that an aggregate report can be shared with the whole practice team during a meeting. From there, the staff should discuss goals for needed changes and plan ways to implement new protocols to make improvements, as well as a future re-audit to assess the success (or lack thereof) of implemented changes to rectify deficiencies.29

Clinicians need to remember that the purpose of an audit is to support improvements, it is not intended to be punitive.29,30 If errors are found within a record, it should not be altered in a way that covers the error so that it cannot be seen. Instead, a dated follow-up note with explanation and measures taken to address the error should become part of the record.

Conducting an internal audit should not require an extensive amount of time for staff members, including the coordinator. The adopted audit form may be created by the office or adopted from online forms available for purchase. The form may be one to two pages of a checklist regarding patient care and services to indicate that the record does or does not contain the information it should.29 There should be space on the form for comments by the evaluator.

For added convenience, the form could include directions on where to find certain items within the electronic health record software interface, and/or screenshots of buttons to click for needed information, but otherwise, the audit form does not need to be overly sophisticated.

The literature is mixed regarding the efficacy of clinical audits.29 However, a systematic review found that adoption of a new audit system produced the following results: compliance with standards increased significantly for a sustained 10-year period; implementation of a one-time random audit resulted in 50% improved compliance upon follow up; and when audit systems were inactivated, a decline in record keeping accuracy ensued.4 In addition to audit systems, follow-up reminders of correct protocols and continuing education courses can be impactful when they target identified areas of weakness.3,29 Internal audit systems can help dental team members implement protocols that support best practices for patient care and recordkeeping.30

Conclusion

Ensuring all team members are on-board with a plan of how to conduct daily clinical practices and recordkeeping supports consistency in the office and reduces confusion. Even for recently hired team members, completing a couple of chart audits may help them become familiar with electronic dental record software and office protocols. Dental record audits are also useful quality checkpoints to increase the evidentiary value of records for forensic odontology purposes.28

References

- American Dental Association Council on Dental Practice Division of Legal Affairs. Dental Records. Available at: store.ada.o/g/catalog/dental-practice-dental-records-3273. Accessed September 27, 2023.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice. Available at: adha.org/wp-content/uploads/떖/著/떐-Revised-Standards-for-Clinical-Dental-Hygiene-Practice.pdf. Accessed September 27, 2023.

- Villarosa AR, Maneze D, Ramjan LM, Srinivas R, Camilleri M, George A. The effectiveness of guideline implementation strategies in the dental setting: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2019;14:1-16.

- Amos KJ, Bearman M, Palermo C. Evidence regarding teaching and assessment of record-keeping skills in training of dental studentsJ J Dent Educ. 2015;79:1222-1229.

- Stow L, Higgins D. The importance of increasing the forensic relevance of oral health records for improved human identification outcomes. Aust J Forensic Sci. 2019;51:49-56.

- American Board of Forensic Odontology. Diplomates Reference Manual. Available at : abfo.org/wp-content/uploads/떌/葔/ABFO-DRM-Section-6-Appendix-April-2020-New-page-numbers.pdf. Accessed September 28, 2023.

- American Dental Association. State Dental Boards. Available at: ada.org/en/resources/licensure/state-dental-boards. Accessed September 28, 2023.

- Morgan R. Quality evaluation of clinical records of a group of general dental practitioners entering a quality assurance programme. Br Dent J. 2001;191:436-441.

- Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario. Guidelines: Dental Recordkeeping. Available at: az184419.vo.msecnd.net/rcdso/pdf/guidelines/RCD_O_Guidelines_Dental_Recordkeeping.pdf. Accessed September 28, 2023.

- Savic Pavicin I, Jonjic A, Maretic I, Dumancic J, Ceshko AZ. Maintenance of dental records and forensic odontology awareness: a survey of Croatian dentists with implications for dental education. Dent J. 2021;9:1-11.

- Brown L. Inadequate record keeping by dental practitioners. Aust Dent J. 2015;60:497-502.

- American Dental Association. The Dentist’s Role in Forensic Identification. Available at: store.ada.org/catalog/dentists-role-in-forensic-identification-2155. Accessed September 28, 2023.

- Riley A. The role of the dentist in identifying missing and unidentified persons. J Acad Gen Dent. 2015;63:54-57.

- Delattre V. Antemortem dental records: Attitudes and practices of forensic dentists. J Forensic Sci. 2007;52:420-422.

- Adams C, Carabott R, Evans S. Forensic Odontology: An Essential Guide. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2014.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Disclosures for Public Health Activities. Available at: hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/special/publichealth/publichealth.pdf. Accessed September 27, 2023.

- American Society of Forensic Odontology. Dental Record Retention. Available at: asfo.org/wp-content/uploads/떖-ASFO-Record-Retention.pdf. Accessed September 27, 2023.

- Senn DR, Weems RA. Manual of Forensic Odontology. 5th ed. Boca Raton, Florida: Taylor & Francis; 2013.

- Borrman H, Dahlbom U, Loyola E, Rene N. Quality evaluation of 10 years patient records in forensic odontology. Int J Legal Med. 1995;108:100-104.

- Interpol Annexure 12. Methods of Identification. Available at: interpol.int/en. Accessed September 23, 2023.

- Barbaro A. Manual of Forensic Science: An International Survey. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press; 2017.

- Hand JS, Reynolds WE. Dental record documentation in selected ambulatory care facilities. Public Health Rep. 1984;99:583-590.

- Osborn JB, Stoltenberg JL, Newell KJ, Osbron SC. Adequacy of dental records in clinical practice: a survey of dentists. J Dent Hyg. 2000;74:297-306.

- Kieser JA, Laing W, Herbison P. Lessons learned from large-scale comparative dental analysis following the South Asian Tsunami of 2004. J Forensic Sci. 2006;51: 09-112.

- McAndrew R, Ban J, Playle R. A comparison of computer- and hand-generated clinical dental notes with statutory regulations in record keeping. Eur J Dent Educ. 2012;16:e117-e121.

- Puri I, Thakrar I, Makdissi J. A clinical audit to assess the quality of dental radiographic reports [abstract only]. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2019;128:E175-E176.

- Cole A, McMichael A. Audit of dental practice record-keeping: a PCT-coordinated clinical audit by Worcestershire dentists. Prim Dent Care. 2009;16:85-93.

- Al-Azri AR, Harford J, James H. Awareness of forensic odontology among dentists in Australia: are they keeping forensically valuable dental records? Aust Dent J. 2016;1:120-108.

- Benjamin A. Audit: How to do it in practice. BMJ. 2008;336:1241–1245.

- Malleshi SN, Joshi M, Nair SK, Ashraf I. Clinical audit in dentistry: From a concept to an initiation. Dent Res J. 2012;6:665-670.

- Hook H. A guide to clinical audit for the dental team. Br Dent J Team. 2020;7:34-37.

From Dimensions in Dental Hygiene. October 2023; 21(9):28-31