Top 10 Questions About AP Answered

Follow these strategies to help determine when antibiotic prophylaxis is necessary before treating patients with cardiovascular problems.

This course was published in the December 2011 issue and expires December 2014. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the indications for antibiotic prophylaxis among patients with cardiovascular problems.

- Detail the antibiotic regimen prescribed for those patients who require antibiotic prophylaxis before receiving dental treatment.

- Discuss the role of the dental hygienist in the provision of antibiotic prophylaxis.

Determining whether antibiotic prophylaxis (AP) is necessary when providing oral health care to patients with cardiovascular problems can be a confusing process. Dental hygienists need to lead the dental team on these issues and, thus, must be well informed about the indications for AP.

What are the Indications for Antibiotic Prophylaxis in the Dental Office?

The indications for AP in patients with cardiovascular problems changed dramatically with the release of the most recent American Heart Association guidelines in 2007.1-3 Patients in the moderate risk group should no longer receive AP. The moderate risk group includes: congenital cardiac malformations other than those listed in the high-risk and negligible-risk categories; acquired valvular dysfunction (eg, rheumatic heart disease); hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; and mitral valve prolapse with valvular regurgitation and/or thickened leaflets.

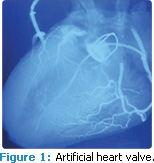

The 2007 American Heart Association guidelines (Table 1) recommend AP for higher risk groups, including:

1. Patients with prosthetic cardiac valves (Figure 1);

2. Patients with previous infective endocarditis (Figure 2);

3. Patients with certain congenital heart diseases (Figure 3);

4. Cardiac transplant recipients (Figure 4).

How are Higher Risk Groups Identified?

Identifying patients with prosthetic cardiac valves, previous infective endocarditis, certain congenital heart diseases, and cardiac transplants is accomplished by thorough review of patients’ medical history and by asking specific questions about past surgical procedures and hospitalizations. Patients who have prosthetic cardiac valves, certain congenital heart diseases, and heart transplants have all undergone cardiac surgery. Patients with previous infective endocarditis have been hospitalized for treatment of the endocarditis.

Patients who complete the medical and dental history forms quickly may not understand the relevance of these questions to dental practitioners. Whenever there is confusion regarding a patient’s heart condition, the patient’s primary care physician or cardiologist should be contacted.

What are the Possible Complications when Antibiotic Prophylaxis is Not Implemented?

Infective endocarditis is the most serious complication that can arise when AP is not implemented before dental treatment. The efficacy of AP, however, is unclear.4 Nonetheless, AP should be administered to patients in higher risk groups 30 minutes to 60 minutes before dental treatment to allow the antibiotic to reach a sufficient blood level. The American Heart Association guidelines state that if the dosage of antibiotic is not administered before the procedure, the dosage may be administered up to 2 hours after the procedure is completed.1,2

What is the Rationale for Changing the Guidelines?

The American Heart Association Writing Committee reviewed all of the studies and science concerning the issue of AP and dental treatment. The committee determined that there was no strong scientific evidence to support AP for the moderate risk group, and that the risks from AP likely outweigh the benefits. Research shows that bacteria get into the bloodstream (bacteremia) after brushing teeth, and probably with flossing and chewing food, as well.5 Therefore, poor oral hygiene and gingivitis may be far more likely to cause infective endocarditis than dental procedures.

Which Dental Procedures Require Antibiotic Prophylaxis?

Previous American Heart Association guidelines provided a list of procedures that were more likely to cause bacteremia (bacteria in the bloodstream), but the 2007 guidelines do not provide these specifics. They do note, however, that the risk of bacteremia increases during procedures that manipulate the gingival tissues, disrupt the periapical region of infected teeth, or perforate the oral mucosa. Also, any dental procedure that goes below the gingival margin can cause bacteremia. The guidelines do specifically address procedures that do not require AP (Table 2).

|

What if it’s Unclear Whether a Patient is High Risk?

If confusion exists about whether a patient needs AP, dental hygienists should refer back to the American Heart Association guidelines. If the patient is not in the higher risk group, there is no indication for AP. If it is unclear whether a patient belongs in the higher risk group, consult the patient’s physician. A patient’s recollection of what the physician ordered should not be relied upon. Dental staff should request copies of any written recommendations made by the physician so they can be included in the patient’s chart. This is important not only for treatment, but also for documentation purposes.

What is the Regimen for Antiobiotic Prophylaxis?

The 2007 AHA guidelines contain a specific regimen for AP before dental procedures, and it should be readily available to all practitioners in the office (Table 3). The drug of choice for patients without penicillin allergies is amoxicillin.

What are the Problems Associated with Patients Taking Antibiotics?

Antibiotics have been overprescribed to treat a variety of conditions for many years. The most significant problem is that, on rare occasions, patients can have serious allergic reactions to a drug. In addition, the overuse of AP may result in the development of strains of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Finally, the use of antibiotics is an expense to the health care system that is not justified when used unnecessarily.

Therefore, dental professionals should limit their use to those situations where evidence shows a benefit. Because there is no definitive study of AP use in dental practice, experts, such as those who comprise the AHA committee, must be relied upon.

What is the Dental Hygienist’s Role in Antiobiotic Prophylaxis?

Dental hygienists are responsible for understanding their patient’s medical histories, especially as they relate to medical problems that might be affected by the provision of invasive or stressful oral health care procedures. They must also remain up-to-date on professional guidelines, such as those published by the American Heart Association. Dental hygienists need to understand the medical conditions and procedures that are considered for AP, as well as the antibiotic protocols. Patient education and compliance issues must also be addressed. Dental hygienists must find the answers to the following questions:

- Does the patient know that AP is recommended?

- Did the patient fill the prescription and take it as instructed prior to the appointment?

- Has the patient’s physician provided instructions to the patient and the dental office in cases where it is unclear whether he or she requires AP?

Because dental hygienists see patients on a routine basis, they are well positioned to identify new health issues. The vast majority of medical problems that arise in the dental office are avoidable if patients are effectively screened during the medical history review.

How can Dental Hygienists Keep the Antibiotic Prophylaxis Guidelines Top of Mind?

All dental offices should have a copy of the Journal of the American Dental Association special supplement concerning AP.1 Posting the tables from this issue in the office will keep the guidelines top of mind. Also, seeking out high-quality continuing education programs on the subject is important because the antibiotic prophylaxis guidelines for cardiac and orthopaedic joint patients, for example, change over time. Dental hygienists can take the lead at staff meetings, and organize evidence-based discussions on the important issues surrounding the care of medically complex patients.

PHOTO CREDITS:

FIGURE 1: SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

FIGURE 2: DR. E. WALKER / PHOTO RESEARCHERS, INC

FIGURE 3: SIMON FRASER/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

FIGURE 4: KLAUS GULDBRANDSEN/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

REFERENCES

- Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:739–760.

- Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2007;116:1736–1754.

- Lockhart PB. Guidelines for prevention of infective endocarditis: an explanation of the changes. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139(Suppl):2S.

- Lockhart PB, Loven B, Brennan MT, Fox PC. The evidence base for the efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis in dental practice. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:458–474.

- Lockhart PB, Brennan MT, Thornhill M, et al. Poor oral hygiene is a risk factor for infective endocarditis-related bacteremia. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:1238–1244.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. December 2011; 9(12): 50-53.