Expand Your Risk Assessment Protocol

Evaluate patients’ risk of oral cancer and other health problems by incorporating alcohol screening into your practice.

This course was published in the December 2011 issue and expires December 2014. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the relationship between alcohol use and oral cancer and other health problems.

- Discuss the dental hygienist’s role in the risk assessment of hazardous drinking.

- Detail the different types of alcohol screening tests available for use in clinical practice.

As prevention specialists, dental hygienists play a vital role in health screening and risk assessment.1 The American Dental Hygienists’ Association asserts in its Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice that dental hygienists are ethically obligated to: apply problem-solving in decision-making; take action to promote patient safety and well-being; consult with other health care professionals when appropriate; thoroughly examine the head, neck, and oral cavity; and assess risk factors for tobacco exposure and alcohol use.2 Tobacco cessation and intervention are responsibilities familiar to dental hygienists, but alcohol screening may be a new addition to the dental hygienist’s risk assessment armamentarium.

Risk Assessment

Dental hygienists perform risk assessments every day with patients for a variety of health problems, such as caries, periodontal diseases, and diabetes.3 But alcohol risk assessment is not commonly performed by medical or dental professionals. A variety of factors, including lack of training, disregarding alcohol as a risk factor, questioning its relevance to practice, and fear of offending patients, may hinder health care workers from incorporating alcohol risk assessment into practice.4-6

Medical and dental professionals are well positioned, however, to effectively screen for alcohol problems. Two studies by Miller et al reported positive results when health care workers performed routine alcohol risk assessments in daily practice. In a study of dental patients, more than 75% had positive opinions about alcohol screening by their dentist, and 25% scored positive on an alcohol screening test, indicating hazardous drinking.6 In the medical study, more than 90% of patients in a primary care clinic had positive opinions about alcohol screening by their physician.5 Patients in both studies believed it was important for dental and medical professionals to ask questions about alcohol use, and they were not offended by such screening.5,6

Dental hygienists are often the first line of defense in the early detection of oral cancer. By adding a few questions about alcohol use to the patient health history form and interview, dental hygienists can improve screenings in their practice, which may decrease patients’ risks for developing other long-term health complications.

Alcohol as a Risk Factor for Oral Cancer

Alcohol is a risk factor for oral cancer, which affects approximately 34,000 people in the United States every year, resulting in approximately 6,900 deaths.7,8 Men are twice as likely to be diagnosed with oral cancer than women, and the average age of diagnosis is 62 years. More than 50% of oral cancers are diagnosed in later stages, resulting in poor survival rates.9 Only 50% of individuals with oral cancer survive longer than 5 years.7 Dental professionals need to be diligent in educating the public about risk factors for oral cancer and in screening efforts, so that oral cancer can be diagnosed at an early, more easily treated stage.1,9–11 Detected lesions measuring less than 2 cm are linked to much higher cure and survival rates.12

Common risk factors associated with oral cancers include age, tobacco use, alcohol use, sun exposure, poor nutrition, and human papillomavirus (HPV).7,8 Tobacco and alcohol use remain the strongest risk factors, although people with oral and oropharyngeal cancer linked with HPV infection are less likely to be smokers or drinkers. Approximately eight out of 10 people with oral cancer use tobacco, and approximately seven out of 10 patients with oral cancer are heavy drinkers.7 The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines “heavy” drinking as more than two drinks per day for men, and more than one drink per day for women.13 “Moderate” drinking is defined as less than that per day. “Binge” drinking is defined as five or more drinks on a single occasion for men and four or more drinks on a single occasion for women.13 The CDC defines one drink as 12 oz of beer, 8 oz of malt liquor, 5 oz of wine, or 1.5 oz of 80-proof liquor.13 Alcohol in combination with smoking substantially increases the risk of oral cancer.14,15

|

Dental hygienists routinely perform oral cancer examinations and provide education and follow-up for patients exhibiting signs of oral cancer. Adding the consideration of alcohol use as a risk factor might enhance early detection and outcomes.

Alcohol and Other Health Conditions

Heavy drinking is a risk factor for other health issues as well.13 Alcohol affects every system in the body. Some of the physical effects of alcoholism include pancreatic and liver disease; weakened immune system resulting in frequent infections; cardiovascular disease; hypertension; nutritional deficiencies; and an increased risk of cancer. Psychiatric effects include cognitive problems, depression, dementia, and mental confusion. The social effects of alcoholism vary widely and may include: conflicts in relationships, propensity for violence and abuse, and drunk driving. More than half of American adults have had a drink in the past 30 days, with 5% of the total population drinking heavily and 15% of the total population binge drinking.13 Alcoholism is the third leading lifestyle-related cause of death in the US and causes 79,000 deaths each year.13

Hazardous Drinking Among Older Adults

Hazardous drinking in older adults is increasing and often goes unnoticed by health care professionals because the natural aging process masks the symptoms.16,17 The physical and psychological effects of drinking may be exacerbated among older adults, and they can complicate treatment and increase the risk of additional health problems. Older adults are more prone to accidents and falling due to impaired brain cognition.16,17 Many medications interact with alcohol, causing adverse reactions.17 When planning any extensive dental treatment for older adults, careful attention must be paid to the health history.

The effects of hazardous drinking are generally heightened in older adults (Table 1). Clinicians can identify heavy drinking by recognizing the common oral symptoms and noting any decline in self-care or cognitive function.

Incorporating Alcohol Consumption into Risk Assessment Protocols

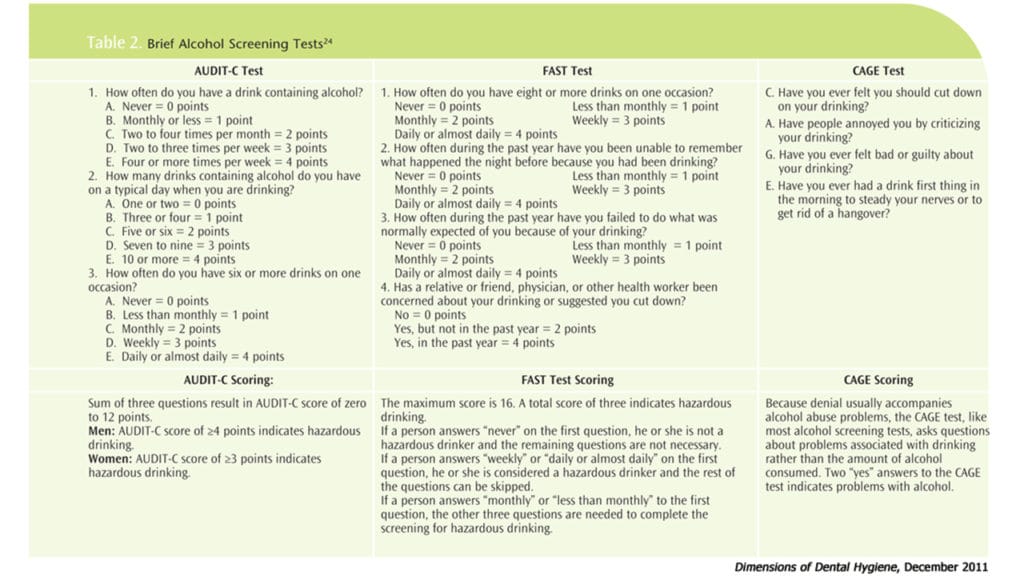

Dental hygienists use the five As of tobacco cessation support—ask, advise, assess, assist, and arrange follow-up—routinely in practice.18 Alcohol screening can be modeled after this method.11 First, a validated brief screening test, such as the AUDIT-C, FAST, or CAGE test, should be used (Table 2).

The AUDIT-Consumption or AUDIT-C is a three-item questionnaire that assesses patients’ risk of heaving drinking.19-21 These three questions can easily be added to an existing health history questionnaire.19 The AUDIT-C is a validated instrument that has been used in primary care settings for brief interventions.19-21 The AUDIT-C is a simpler, modified version of the 10-question AUDIT instrument, a gold standard test designed for brief interventions.22 Answers to each question have five choices and are allotted points. Higher scores indicate an increased likelihood of hazardous drinking.19-21 In men, a score of four, and in women, a score of three is considered positive. The AUDIT and AUDIT-C instruments were designed to screen for hazardous drinking at early stages before problem drinking turns into full addiction.22

The FAST test is another modified version of the original AUDIT alcohol-screening questionnaire that uses four key questions.23 It was designed for use in busy clinical settings. A score of three indicates hazardous drinking.

The CAGE test is an older screening test that asks about historical patterns of drinking.24 Two “yes” answers on the CAGE test indicate problematic drinking. The outcome of these brief screening tests can help open a dialogue with patients about hazardous drinking and the risk factors associated with oral cancers and other health problems. Increasing patients’ awareness may lead to behavior change, earlier diagnosis, and treatment.

![]() Conclusion

Conclusion

Routine screening for alcohol use needs to become an integral part of the dental health history questionnaire and interview. Brief alcohol screening tests can help identify those at risk of developing oral cancer and other significant long-term health problems. With discussion and referral to a primary care physician, alcohol screening can be effective in reducing problem drinking at earlier stages.25 Incorporating risk assessment into practice requires discussion with and education of all members of the dental health care team collaborating in the provision of oral health care. Brief risk assessment tests are intended for screening and referral—they are not intended to diagnose alcoholism.22 After referral, the appropriate health professional will perform further tests to clinically diagnose alcoholism.

REFERENCES

- Van der Waal I, De Bree R, Brakenhoff R, Coebergh JW. Early diagnosis in primary cancer: is it possible? Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2011;16:e300–305.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Standards for clinical dental hygiene practice. Access. Available at: www.adha.org/downloads/adha_standards08.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2011.

- Darby ML, Walsh MM. Dental Hygiene Theory and Practice. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:1238.

- Dyer TA, Robinson PG. General health promotion in general dental practice-the involvement of the dental team. Part 2: a qualitative and quantitative investigation of the views of practice principals in South Yorkshire. Br Dent J. 2006;201:45–51.

- Miller PM, Thomas SE, Mallin R. Patient attitudes towards self-report and biomarker alcohol screening by primary care physicians. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:306–310.

- Miller PM, Ravenel MC, Shealy AE, Thomas S. Alcohol screening in dental patients: the prevalence of hazardous drinking and patients’ attitudes about screening and advice. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:1692–1698.

- American Cancer Society. Oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer. Available at: www.cancer.org/cancer/oralcavityandoropharyngealcancer. Accessed September 22, 2011.

- National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. What you need to know about oral cancer. Available at: www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/wyntk/oral/allpages. Accessed October 5, 2011.

- Brocklehurst P, Kujan O, Oliver O, Sloan P, Odgen G, Shepherd S. Screening programmes for the early detection and prevention of oral cancer (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;11(CD004150):1–28.

- Gomez I, Seoane J, Varela-Centelles P, Diz P, Takkouche B. Is diagnostic delay related to advance-stage oral cancer? A meta-analysis. Eur J Oral Sci. 2009;117:541–546.

- McCann MF, Macpherson L, Gibson J. The role of the general dental practitioner in detection and prevention of oral cancer: A review of the literature. Dent Update. 2008;27:404–408.

- Seoane-Romero JM, Vazquez-Mahia I, Seoane J, Varela-Centellas P, Tomas I, Lopez-Cedrun JL. Factors related to late stage diagnosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2011 July 15. [Epub ahead of print].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol use. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/alcohol. Accessed October 3, 2011.

- Bagnardi V, Blangiardo M, La Vecchia C, Corrao G. Alcohol consumption and the risk of cancer. Alcohol Res Health. 2001;25:263–270.

- Petti S, Scully C. The role of the dental team in preventing and diagnosing cancer: 5. Alcohol and the role of the dentist in alcohol cessation. Dent Update. 2005;32:458–462.

- Rigler S. American Academy of Family Physicians. Alcoholism and the elderly. Available at: www.aafp.org/afp/20000315/1710.html. Accessed October 3, 2011.

- Friedlander AH, Norman DC. Geriatric alcoholism: Pathophysiology and dental implications. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137: 330–338.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Treating tobacco use and dependence. Quick reference guide for clinicians. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/tobacco/tobaqrg.htm. Accessed October 6, 2011.

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C). Arch Intern Med. 1998;158: 1789–1795.

- Bradley KA, Bush K, Epler AJ, et al. Two brief alcohol-screening tests from the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT). Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:821–829

- Frank D, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Effectiveness of the AUDIT-c as a screening test for alcohol misuse in three race/ethnic groups. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:781–787.

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De La Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804.

- Hodgson R, Alwyn T, John B, Thom B, Smith A. The FAST alcohol screening test. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37:61–66.

- Buddy T. Short alcohol tests ideal for healthcare screening. Available at: www.alcoholism.about.com/od/a/tests.htm?p=1. Accessed October 6, 2011.

- Vasilaki EI, Hosier SG, Cox WM. The efficacy of motivational interviewing as a brief intervention for excessive drinking: a meta-analytic review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:328–335.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. December 2011; 9(12): 44, 47-49.