STEPHANIE STEELE, DDS

STEPHANIE STEELE, DDS

Oral Health Effects of Antiresorptive Medications

Oral health professionals need to be familiar with bisphosphonates and other antiresorptive medications due to their impact on dental health.

This course was published in the August 2018 issue and expires August 31, 2021. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the prevalence of osteoporosis, and the types and properties of antiresorptive drugs used to manage medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw.

- Describe when medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw was first reported, the estimated incidence rate, and factors that contribute to this condition.

- Explain the oral anatomy most commonly affected, as well as clinical strategies for managing patients with medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw.

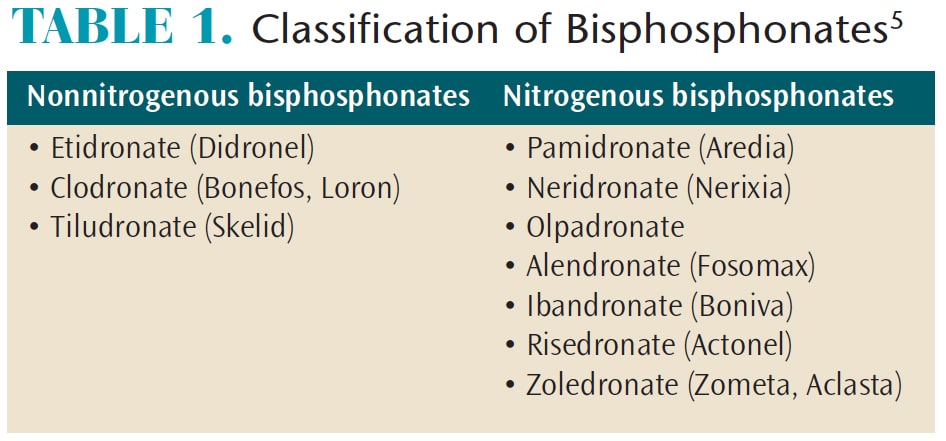

Bisphosphonates are analogs of pyrophosphates that bind selectively to bone minerals.4Clinically, they reduce bone pain and delay pathological skeletal events, including fractures.5 Differentiated by chemical structure, nonnitrogenous and nitrogenous bisphosphonates (Table 1, page 39) are deposited into the mineralized structures and lead to osteoclast death during resorption. Potency depends on the composition, with nitrogenous bisphosphonates being 10-fold to 100-fold more potent, and with a broader therapeutic window than nonnitrogenous bisphosphonates.6 Delivery can be oral or intravenous, although adverse effects on renal function have been reported when higher doses are infused intravenously.7

MECHANISM OF ACTION

Bisphosphonates inhibit osteoclastic bone resorption in a different fashion than other antiresorptive agents.8–10 They attach to hydroxyapatite binding sites on bony surfaces undergoing active resorption, where they impair the ability of the osteoclasts to form the ruffled border, adhere to the bony surface, and produce the protons necessary for continued bone resorption.8,9,11 They also reduce osteoclast activity by decreasing osteoclast progenitor development and recruitment, and by promoting osteoclast apoptosis.

The mechanism of RANKL inhibitors is to inhibit the osteoclastogenesis by interfering the binding of RANK on osteoclast precursors and RANKL from osteoblasts. Without activated osteoclasts, the metabolism of bone is affected.2

TERMINOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Of concern to the dental community are reports of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. However, it becomes confusing when multiple terms are used to refer to the same condition. Early reports mentioned a condition called “phossy jaw.”12Subsequently, the terms osteonecrosis of the jaw, bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw, antiresorptive drug-related osteonecrosis of the jaw, and medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw were introduced; medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw replaced bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in 2014 due to the growing number of osteonecrosis cases associated with other antiresorptive medications (Figure 1, page 37, and Figure 2).

Marx13 initially reported on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in 2003, and this research was followed by other clinical case reports that showed similar clinical patterns in patients who took bisphosphonates.12,14,15 These reports brought attention to the clinical outcome of atypical avascular jawbone necrosis. Initially, medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw was thought to be associated with the intravenous (IV) forms of nitrogen bisphosphonates; however, reports have since shown medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw is also associated with less potent oral bisphosphonates, though the incidence is reported to be low.6 The clinical presentation of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw is similar to osteoradionecrosis of the jaw and osteomyelitis of the jaw.12,14,15 Retrospective studies and case reports have indicated the incidence rate of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw ranges from 0.8%% to 12.0%. It has mostly been found in the mandible, with fewer reports of occurrence in the maxilla or both jaws.5In addition, research of various malignancies, such as multiple myeloma, breast cancer, or prostate cancer, showed that subjects who were taking, or had taken, bisphosphonates had a higher incidence of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw.16 A multicenter retrospective study showed that medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw had 2% to 11% incidence in patients with multiple myeloma, 1% to 7% incidence in those with breast cancer, and 6% to 15% incidence in patients with prostate cancer.12

Mashiba et al17 proposed that through its antiresorptive properties, bisphosphonates inhibit natural bone remodeling, which eventually damages and reduces the mechanical properties of the bone. Marx et al6indicated that local osteoporosis might lead to osteonecrosis of the jaw. Based on the literature, the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) described risk factors that can lead to the development of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (Table 2, page 39).18 Other factors that may play a role include diabetes, smoking, alcohol use, poor oral hygiene, and chemotherapeutic drugs.

STAGING AND TREATMENT

In defining the staging and treatment of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw, the AAOMS task force classified patients into five categories,18 ranging from a patient presenting with no symptoms and needing no treatment to individuals in stages 0, 1, 2, and 3. Various stages require different treatment strategies. For example, pain management and infection control are necessary for each stage, while surgical treatment is indicated for stages 2 and 3. Stage 3 will likely require surgical debridement, with possible resection of sites. However, studies have indicated that surgical procedures in stages 1 and 2 may help achieve optimal results.19,20

In addition, in 2014 Franco et al20 evaluated the outcomes of 266 medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw lesions using a new dimensional stage classification. Clinicians can also use this staging system to make treatment recommendations.

DISCONTINUATION OF BISPHOSPHONATES

The role of a “drug holiday” remains controversial. In 2009, the AAOMS recommended withholding oral bisphosphonates for up to 3 months before and after a surgical procedure.18 However, a recent study by Hasegawa et al21 did not support the effectiveness of a drug holiday on the outcome of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients taking oral bisphosphonates. For patient on IV bisphosphonates, short-term discontinuation might not allow for better outcomes, while long-term discontinuation might be beneficial in stabilizing established sites of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw, reducing the risk of new site development and clinical symptoms.22 Based on the recommendation of McClung et al,23 the decision to discontinue antiresorptive medication relies on the patient’s fracture risk, T score, and history of hip

or spine fracture. Discussion with the patient’s physician regarding cessation of bisphosphonates is mandatory in medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw treatment.

MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

For patients taking these drugs, good oral hygiene and regular dental visits are essential. Prior to starting bisphosphonate therapy, addressing existing dental issues is a best-practice strategy. Based on a study of 731 patients, Salgarello et al24 made the following recommendations:

- Finish all necessary dental procedures, such as tooth extractions, prior to bisphosphonate treatment, as extraction was the most frequent procedure associated with the development of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw.25

- Reevaluate oral and periodontal health every 3 months to 6 months.

- For patients already under bisphosphonate treatment, careful follow-up exams should be scheduled every 3 months to 6 months.

- If dental surgery is performed, consider a drug holiday based on physician recommendations.

In order to minimize surgical trauma:

- When possible, consider root canal treatment to save the tooth or teeth.

- Reduce the level of inflammation in the surgical sites by completing anti-inflammatory treatment prior to dentoalveolar surgery.

- If appropriate, consider atraumatic extraction using orthodontic elastics26 or careful elevation of the tooth.

- Consider referring patients to surgical specialists with greater additional experience.

- Prescribe an antibacterial rinse (eg, chlorhexidine) prior to the procedure and during the post-operative phase.

- Use antibiotics perioperatively.18,27

DENTAL TREATMENT

Generally speaking, if routine dental treatment—such as prophylaxis, fluoride carriers, dental restorations, or dentures—is indicated, no special precautions are required for these patients. However, if more invasive treatment is needed, such as extractions, periodontal surgery, or surgical root canal treatment, use of bisphosphonates should be delayed for a month to allow sufficient time for bone recovery and healing.6

Restorative Dentistry: Because dental disease, such as caries leading to periapical infections and periodontitis, has been associated with bisphosphonate-related bone necrosis, patients taking these drugs should have a dental examination and address any dental conditions prior to starting the medication.28 Clinicians must be careful to avoid soft tissue trauma during restorative treatment. Additionally, removable prosthesis (eg, partial or complete dentures) should be carefully inspected and adjusted to prevent soft tissue trauma.

Periodontal Treatment: The goal of periodontal therapy is to eliminate infection and to prevent the spread of infection to other areas of the oral cavity and body. Both periodontal disease and treatment pose a risk for medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw, for patient taking bisphosphonates;6 therefore, when treating periodontal disease, clinicians should handle tissues carefully to minimize tissue trauma. Marx et al6 reported 11.2% of bisphosphonate-induced bone exposure was related to periodontal surgery. Bone necrosis after periodontal surgery and other surgical procedures might be due to the exposure of bone following flap replacement and a lack of normal healing of the bone and surrounding tissue due to low cellular proliferative capacity.29 Therefore, during periodontal surgery, primary closure of wounds should be attempted (when possible) to enhance tissue healing.

Orthodontic Therapy: Research into tooth movement in animals and humans using bisphosphonate medications reported no contraindications to orthodontic therapy.29 Although treatment for patients taking bisphosphonates is not contraindicated, clinicians should be cognizant and avoid potential soft tissue damage that can be caused by brackets and archwires.

Endodontics: No evidence has been reported to show an association between endodontic treatment and medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients.30 It is recommended that nonsurgical endodontic treatment be rendered with the goal of avoiding soft tissue and periapical trauma.

Endodontics: No evidence has been reported to show an association between endodontic treatment and medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients.30 It is recommended that nonsurgical endodontic treatment be rendered with the goal of avoiding soft tissue and periapical trauma.

Extractions/Dental Implants: Extractions and implants are considered invasive osseous dental procedures that can trigger osteonecrosis of the jaw for patients taking bisphosphonates. These invasive procedures should be carefully planned; AAOMS recommendations include:2

For patients about to initiate bisphosphonate therapy:

- Only begin bisphosphonate therapy after optimum oral health is achieved.

- Nonrestorable teeth should be extracted at this time and other invasive procedures—including dental implants—should be done at this time.

- Bisphosphonate therapy can be initiated after optimum osseous healing is achieved. Maintenance of oral hygiene and follow-up are necessary.

For patients receiving bisphosphonate therapy:

- No strong evidence exists in support of, or as an alternative to, a drug holiday for patients taking bisphosphonates. The AAOMS recommends a 2-month drug-free period to reduce bisphosphonate levels for an invasive procedure. This decision is made with the prescribing physician’s consult.

- When a patient is on oral bisphosphonates for less than 4 years and the clinical risk factors are at a minimum, extractions/dental implant procedures can be carried out, provided the patient is informed of the benefits and risks associated with the procedure. Informed consent is required.

- When a patient is on bisphosphonates for less than 4 years and is taking corticosteroids or anti-angiogenic medications, the prescribing physician is contacted to consider a drug-holiday. Bisphosphonates can be restarted after optimum osseous healing is achieved. Corticosteroids or anti-angiogenic medications in combination with bisphosphonate therapy can increase the risk of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw.

- When a patient is on bisphosphonates for more than 4 years, the prescribing physician should be contacted concerning a drug holiday. Bisphosphonates can be restarted after optimum osseous healing is achieved.

![]() SUMMARY

SUMMARY

Bisphosphonates are the most commonly prescribed antiresorptive agents1,2 and are first-line drugs for treating post-menopausal osteoporosis. Clinicians should be aware of the oral health effects associated with these medications, and use special care in treating these patients. When managing patients taking bisphosphonates or those presenting with signs of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw, the need to maintain optimal oral hygiene and have regular follow-up care should be emphasized. When possible and prior to starting these medications, addressing existing dental issues is a best-practice strategy.19 Finally, from a clinical perspective, oral health professionals need to be careful to avoid soft tissue trauma when performing dental treatment on this patient population.

BONUS ONLINE CONTENT

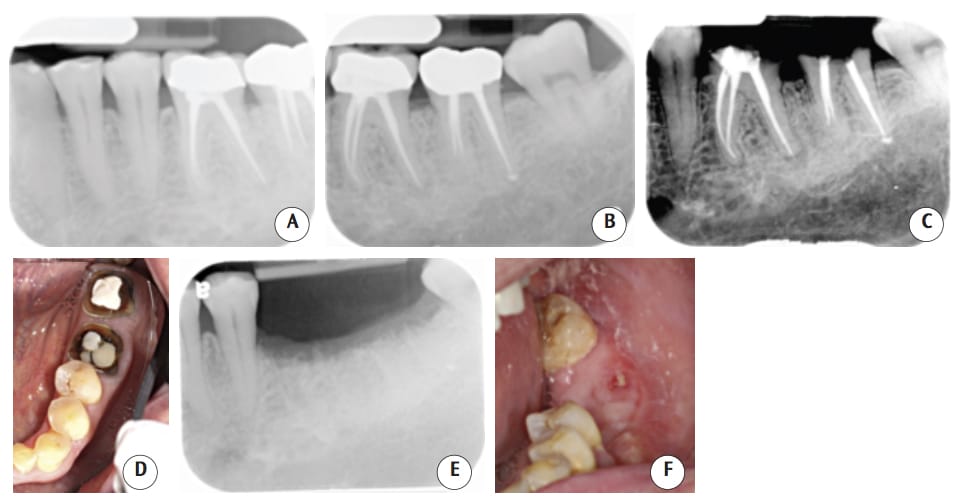

(Figures 3A through 3F): The patient was taking oral alendronate sodium (35 mg) once a week for osteoporosis. He presented to the dental clinic to replace the crowns on teeth #18 and #19. As the remaining tooth structure was inadequate, extraction and implant placement was suggested. Following surgical extraction, the socket was thoroughly debrided, grafted with freezedried bone allograft, and covered by a nonresorbable membrane and sutured. One month after surgery, the patient reported mild discomfort. Three months after surgery, the tissue healed well and without any bone exposure. The radiographic films showed bone fill on the extraction site. However, 4 months after surgery, a 4×1.5-mm asymptomatic area of exposed bone was found in the lower left quadrant. The patient was advised to stop taking the bisphosphonate for at least 3 months to allow spontaneous tissue healing, and a medical consult form was sent to his physician addressing his medication. The patient was advised to clean this area with 0.12% chlorhexidine mouthrinse, but no antibiotic was prescribed. Six months after surgery, a 2×3-mm asymptomatic lesion still presented, and with no adjacent erythematic tissue. Two sessions of ozone therapy were provided, after which, healing proceeded uneventfully

REFERENCES

- Looker AC, Sarafrazi Isfahani N, Fan B, Shepherd JA. Trends in osteoporosis and low bone mass in older US adults, 2005-2006 through 2013-2014. Osteoporo Int. 2017;28:1979–1988.

- Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Fantasia J, et al. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw—2014 update. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;72:1938–1956.

- Tanna N, Steel C, Stagnell S, Bailey E. Awareness of medication related osteonecrosis of the jaws (MRONJ) amongst general dental practitioners. Br Dent J. 2017;222:121–125.

- Gutta R, Louis PJ. Bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaws: science and rationale. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104:186–193.

- Siddiqi A, Payne AG, Zafar S. Bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of the jaw: a medical enigma? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108:e1–e8.

- Marx RE, Sawatari Y, Fortin M, Broumand V. Bisphosphonate-induced exposed bone (osteonecrosis/osteopetrosis) of the jaws: risk factors, recognition, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:1567–1575.

- Markowitz GS, Appel GB, Fine PL, et al. Collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis following treatment with high-dose pamidronate. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:1164–1172.

- Rodan GA, Fleisch HA. Bisphosphonates: mechanisms of action. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2692–2696.

- Sato M, Grasser W, Endo N, et al. Bisphosphonate action. Alendronate localization in rat bone and effects on osteoclast ultrastructure. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:2095–2105.

- Fleisch H. Bisphosphonates: mechanisms of action. Endocr Rev. 1998;19:80–100.

- Colucci S, Minielli V, Zambonin G, et al. Alendronate reduces adhesion of human osteoclast-like cells to bone and bone protein-coated surfaces. Calcif Tissue Int. 1998;63:230–235.

- Abu-Id MH, Warnke PH, Gottschalk J, et al. “Bis-phossy jaws”—high and low risk factors for bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of the jaw. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2008;36:95–103.

- Marx RE. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1115–1117.

- Vieillard MH, Maes JM, Penel G, et al. Thirteen cases of jaw osteonecrosis in patients on bisphosphonate therapy. Joint Bone Spine. 2008;75:34–40.

- Ruggiero SL, Mehrotra B, Rosenberg TJ, Engroff SL. Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with the use of bisphosphonates: a review of 63 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:527–534.

- Bamias A, Kastritis E, Bamia C, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer after treatment with bisphosphonates: incidence and risk factors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8580–8587.

- Mashiba T, Hirano T, Turner CH, Forwood MR, Johnston CC, Burr DB. Suppressed bone turnover by bisphosphonates increases microdamage accumulation and reduces some biomechanical properties in dog rib. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:613–620.

- Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Assael LA, et al. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws—2009 update. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:2–12.

- Vescovi P, Manfredi M, Merigo E, Meleti M. Early surgical approach preferable to medical therapy for bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:831–832.

- Franco S, Miccoli S, Limongelli L, et al. New dimensional staging of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw allowing a guided surgical treatment protocol: long-term follow-up of 266 lesions in neoplastic and osteoporotic patients from the University of Bari Int J Dent. 2014;2014:935657.

- Hasegawa T, Kawakita A, Ueda N, et al. A multicenter retrospective study of the risk factors associated with medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw after tooth extraction in patients receiving oral bisphosphonate therapy: can primary wound closure and a drug holiday really prevent MRONJ? Osteoporo Int. 2017;28:2465–2473.

- Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Landesberg R, Mehrotra B. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:369-376.

- McClung M, Harris ST, Miller PD, et al. Bisphosphonate therapy for osteoporosis: benefits, risks, and drug holiday. Am J Med. 2013;126:13–20.

- Salgarello S, Mensi M, Cella F, Stranieri F, Di Rosario F. BRONJ prevention: 9 years of clinical practice. Ann Stomatol (Roma). 2014;5(2 Suppl):39–40.

- Aljohani S, Fliefel R, Ihbe J, Kuhnisch J, Ehrenfeld M, Otto S. What is the effect of anti-resorptive drugs (ARDs) on the development of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) in osteoporosis patients: A systematic review. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2017;45:1493–1502.

- Regev E, Lustmann J, Nashef R. Atraumatic teeth extraction in bisphosphonate-treated patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:1157–1161.

- Lodi G, Sardella A, Salis A, Demarosi F, Tarozzi M, Carrassi A. Tooth extraction in patients taking intravenous bisphosphonates: a preventive protocol and case series. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:107–110.

- Kos M. Association of dental and periodontal status with bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. A retrospective case controlled study. Arch Med Sci. 2014;10:117–123.

- Consolaro A. The use of bisphosphonates does not contraindicate orthodontic and other types of treatment! Dental Press J Orthod. 2014;19:18–26.

- Moinzadeh AT, Shemesh H, Neirynck NA, Aubert C, Wesselink PR. Bisphosphonates and their clinical implications in endodontic therapy. Int Endod J. 2013;46:391–398.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. August 2018;16(8):37-40.

SUMMARY

SUMMARY