HEDGEHOG94/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

HEDGEHOG94/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

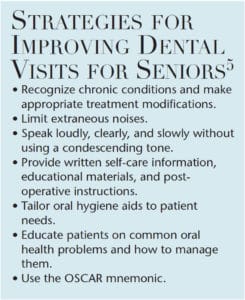

Strategies for Treating Seniors

Identifying common oral health problems, chronic conditions, and physical/ motor disorders is key to ensuring successful dental appointments for mature patients.

This course was published in the August 2018 issue and expires August 31, 2021. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the number of seniors in the United States.

- Discuss common oral health problems experienced by mature adults.

- Explain other mitigating factors, such as cognitive and physical decline, that impact oral health in mature patients.

- List strategies or improving dental appointments for seniors.

ORAL HEALTH ISSUES

Some of the most common conditions affecting mature patients occur with normal aging; however, some are due to medication use or pre-existing health conditions. Xerostomia is the most frequently seen condition in mature adults, affecting 30% of those age 65 and older and 40% of those age 80 and older.4–7 Xerostomia is most often caused by medication use, such as anticholinergics; sympathomimetics; tricyclic antidepressants; sedatives; tranquilizers; antihistamines; cytotoxic agents; anti-Parkinson, anti-epilepsy, and antidiarrheal medications; and expectorants.4–7 Additionally, Sjögren syndrome, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, Alzheimer’s disease, hepatitis C, thyroid gland diseases, adrenal conditions, and psychogenic states are all commonly associated with an increased prevalence of xerostomia.5,7

Xerostomia typically leads to other oral problems such as caries, periodontal diseases, angular cheilitis, dysphagia, and oral cancer.4–7 Mature adults may not realize they are experiencing xerostomia and may have lifestyle habits that further exacerbate the condition, such as drinking sugary, acidic beverages.5,7 Dental hygienists can educate patients about xerostomia and treat the problem through local and systemic salivary stimulation.4–7 Local measures to treat xerostomia include drinking water frequently; avoiding alcohol and caffeine; using products with fluoride, calcium phosphate, xylitol, and arginine; chewing sugarless gum; consuming vitamin C; and placing an adhesive disc near the salivary gland.5–7 Sialagogues may also be prescribed by a physician to help improve salivary flow after a medical consultation.7

Root caries is common among mature patients due to changes in the oral cavity and lifestyle and behavioral factors.5,8–10 Seniors are at risk for developing caries on the coronal surface of the tooth. Due to the natural wear on the teeth, recession of the gingival tissue, and risk of periodontal involvement, however, these patients are twice as likely to have a carious lesion on the root surface.5,8–10 As patients age, the enamel tends to thin, darken in color, and produce wear facets, increasing the risk of fracturing due to the brittle consistency.5,11 Weakened enamel, in addition to factors such as xerostomia, high sugar intake, poor oral hygiene, and systemic diseases, increases the caries rate in seniors.5,8–10 With high rates of xerostomia, which causes the pH levels in the mouth to be more acidic, mature patients are at risk of increased bacteria and plaque buildup along the coronal margin of teeth.5,8–10In addition, researchers have found many mature adults consume high amounts of sugar due to diminishing taste buds, diet restriction, or through their medications.10 Other diseases, such as dementia, may increase the risk for root caries because they interfere with patients’ abilities to maintain oral hygiene.5,8–10

Risk assessment is key to caries prevention. Oral health professionals should also recommend prescription fluoride and educate patients on smart dietary choices to limit caries risk. Dental hygienists should also determine whether the mature patient is capable of regular, routine self-care. Accommodations with oral hygiene aids and recare appointments should be adjusted if a more tailored oral hygiene regimen is needed.

Angular cheilitis is an endogenous infection commonly seen in seniors. Oral candidiasis occurs when the skin has started to stretch due to a reduction in elasticity, which folds the labial commissures at the angles of the mouth. The folded labial commissures allow saliva to collect and become colonized with Candida and Staphylococcus aureus. Angular cheilitis is common among the edentulous, the immunocompromised, those with ill-fitting dentures, and patients who smack or suck on their lips due to xerostomia. Rarely, it is seen in those with nutritional deficiencies or antibiotic resistance. Signs and symptoms of angular cheilitis include edematous, inflamed, cracked labial commissure angles and irritation like a burning-sensation. Treatment includes evaluating the etiology of the condition and preventing saliva from collecting in the area. An antifungal ointment should be applied to the cracked angles to relieve pain.12

Seniors are also at risk for dysphagia, or difficulty swallowing. Oropharyngeal dysphagia is related to the initiation of the swallow, while esophageal dysphagia deals with difficulty moving the food to the stomach.13–15 A literature review found that dysphagia affects about 15% of the geriatric population.16 Symptoms include painful swallowing, inability to swallow, having the sensation of food getting caught in the throat, drooling, becoming hoarse, regurgitating food, frequent heartburn and acid reflux, and gagging on swallowing.15 Aging itself is not a direct cause of either type of dysphagia, rather it is influenced by other factors such as systemic diseases (eg, stroke) or motor or mechanical causes (eg, sphincter not closing properly).13,15 Oropharyngeal or esophageal dysphagia can cause mature adults to become malnourished and/or dehydrated, lose weight, and develop respiratory problems.13,15

If dysphagia is suspected, dental hygienists should refer patients for additional care. Oral health professionals should also ask mature patients about their eating habits to ensure they are receiving proper nutrition. Dental hygienists can recommend that patients eat more frequently, making sure food pieces are small, in addition to chewing their food several times before swallowing and always washing food down with a glass of water.15

Oral cancer is more frequently seen in seniors than other populations. The average age of oral cancer diagnosis is 62.17 By 2030, oncologists predict oral cancer cases among mature adults will increase by 60%.18 Dental hygienists should provide oral cancer screenings for all patients at every appointment and demonstrate how to perform regular oral cancer screenings at home.

In order to better accommodate seniors, dental hygienists can use the mnemonic “OSCAR.” It helps to provide the best overall assessment and diagnosis so treatment plans can be individualized. The “O” suggests looking orally and deciding on the patient’s dental status. The “S” is used to observe the patient’s systemic condition and to make sure all medical conditions are being monitored. “C” stands for capability, and helps the dental hygienist decide if the senior’s physical and motor abilities are compromised and will perhaps limit the ability to perform self-care. The “A” stands for autonomy, and the “R” stands for reality. Dental hygienists should support seniors in making their own health decisions and helping them understand their oral health status.5

![]() CHRONIC CONDITIONS

CHRONIC CONDITIONS

According to the National Council on Aging, 80% of seniors have one chronic condition and 77% have two or more chronic conditions.2 Due to the oral systemic link, dental hygienists need to educate patients on the relationship between chronic conditions and oral health.

Hypertension affects approximately 62% of men and 67% of women between the ages of 65 and 74 and prevalence increases with age.19 For patients with hypertension, blood pressure should be monitored at every visit. Treatment is contraindicated if readings reach 180/110 mm Hg and the patient should be referred to his or her physician.20 It is important to facilitate a stress-free appointment because an increase in blood pressure may trigger a stroke or cardiac arrest.20 Pain management with local anesthesia may help reduce stress during the dental appointment. When administering local anesthesia with epinephrine to hypertensive patients, the dose should not exceed 0.04 mg per appointment, or two cartridges of local anesthesia with 1:100,000 epinephrine or four cartridges of 1:200,000 epinephrine.21

Approximately 25% of Americans age 65 and older have diabetes, which raises the risk for periodontal diseases.22–24 The relationship between diabetes and periodontal disease is bidirectional; diabetes affects the periodontium and periodontal infection negatively impacts glycemic control. Dental hygienists should educate this patient population on this fact.22,23 Mature adults with diabetes may benefit from nutritional counseling to reduce dietary sugar intake and improve glycemic control. For patients with uncontrolled or poorly controlled diabetes, the patient’s physician should be consulted to determine the need for antibiotic prophylaxis prior to oral surgery.24 Dental hygienists may ask patients with diabetes to provide their most recent A1C score prior to their appointment. An A1C score is a simple blood test conducted every 3 months to evaluate blood glucose levels. It helps both the health care provider and patient grasp how well the diabetes is being managed. An A1C level of 7% or less is typically indicative of well-managed diabetes.25

Approximately 22% of people between the ages of 65 and 74, and 30% of individuals age 75 and older have a type of cancer.26 For patients who have undergone head and neck radiation therapy, the following oral symptoms are common: mucositis, xerostomia, candidiasis, fibrosis, caries, osteoradionecrosis, and periodontal disease.26 Mucositis manifests as erythematous oral mucosa followed by ulcerations and pseudomembranes and is accompanied by pain. Treatment of mucositis often includes pain management with a medicated mouthrinse. Candidiasis is a fungal infection that can result in mouth pain, dysgeusia, and dysphagia. Treatment for candidiasis includes the use of topical antibiotic creams, suspensions, or lozenges. Fibrosis is excess fibrous connective tissue that can develop post-radiation on the lingual, pharynx, and masticatory muscles, which could lead to difficulty with tongue function, dysphagia, or trismus.26 Radiation can cause both acute and latent effects on the salivary glands, inducing xerostomia, both during and long after cancer treatments—raising the risk of periodontitis and caries.5,7 Osteoradionecrosis or necrosis of the bone is another possible side effect of head and neck radiation, but can also be triggered by periodontitis.26 Prior to receiving head and neck radiation, patients should have their oral health stabilized, invasive treatments such as extractions performed, and fluoride applied to reduce the disease and infection during and after radiation treatment.

PHYSICAL/MOTOR DISORDERS

Many older adults experience physical/motor disorders, such as hearing impairment, visual loss, and limited dexterity. For patients with dexterity issues or arthritis, powered toothbrushes, flossing devices, and oral irrigators may help improve self-care. Some patients may also benefit from a toothbrush, floss holder, or interdental brush that has been modified with an extended or enlarged handle.27 For example, handles modified with a Velcro strap, tennis ball, or bicycle handle bar may be easier for these patients to hold.26 Hearing impairment may affect a patient’s ability to communicate or hear oral health education information or post-operative instructions. Dental hygienists should speak loudly, clearly, and slowly without using a condescending tone.28 Removing the dental mask when talking increases communication and allows the patient to read lips. Some patients may wear hearing aids, which should not get wet; therefore, patients may want to remove them prior to treatment if a powered scaling device or air polishing device will be used.29 Repeating instructions may be necessary, along with providing written self-care information, educational materials, and post-operative instructions to reinforce important concepts. Extraneous background noise, such as music, equipment, and talking, should be minimized whenever possible.30 Visual impairment such as cataracts, glaucoma, macular generation, presbyopia, and diabetic retinopathy can reduce a patient’s ability to process information communicated nonverbally.28,30 Therefore, patients should be provided with educational materials and appointment information in large print and adequate lighting for filling out forms.

CONCLUSION

With many mature patients living longer and retaining their dentition, it is imperative that dental hygienists recognize chronic conditions, physical/motor disorders, and oral health problems to make appropriate treatment modifications and improve dental care for this population. Due to the high prevalence of chronic conditions in seniors, dental hygienists need to educate them on the oral systemic link, as well as make changes to patient care to ensure an effective appointment. When treating mature patients with limited dexterity, dental hygienists can tailor oral hygiene aids to adapt to patient’s specific needs. Dental hygienists should recognize common oral findings in patients such as angular cheilitis, xerostomia, root caries, periodontal disease, dysphagia, and oral cancer and provide appropriate oral hygiene instructions to improve patients’ oral and overall health.

REFERENCES

- Administration on Aging, Administration for Community Living, United States Department of Health and Human Services. A Profile of Older Americans: 2016. Available at: giaging.org/ documents/A_Profile_of_Older_Americans__2016.pdf. Accessed July 14, 2018.

- National Council on Aging. Healthy Aging Facts. Available at: ncoa.org/news/resources-for-reporters/get-the-facts/healthy-aging-facts/. Accessed July 16, 2018.

- Slade GD, Akinkugbe AA, Sander AE. Projections of US edentulism prevalence following 5 decades of decline. J Dent Res. 2014; 93:959–965.

- American Dental Association. Aging and Dental Health. Available at: ada.org/en/member-center/oral-health-topics/aging-and-dental-health. Accessed July 14, 2018.

- Parashar P. Help older adults maintain their oral health. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2013;11(3):60–63.

- Quandt SA, Savoca MR, Leng Xiaoyan et al. Dry mouth and dietary quality among older adults in north Carolina. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:439–445.

- Ship JA, Pillemer SR, Baum, BJ. Xerostomia and the geriatric patient. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:535–543.

- Marsh L. Root caries prevention. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2013;11(3):36–38.

- Chi DL, Berg JH, Kim AS, et al. Correlates of root caries experience in middle-aged and older adults within the Northwest practice-based research collaborative in evidence-based dentistry research network. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:507–516.

- Walls AWG, Meurman JH. Approaches to caries prevention and therapy in the elderly. Sage Journals. 2012;24(2):364.

- Dahm T. Caring for older adults residing in institutions. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2016;14(1):52–55.

- American Osteopathic College of Dermatology. Angular Cheilitis. Available at: aocd.org/page/ AngularCheilitis. Accessed July 14, 2018.

- Aslam M, Vaezi MF. Dysphagia in the elderly. Gastroenterol Hepatorl (NY). 2013; 9:784–795.

- Carucci LR, Turner MA. Dysphagia revisited: common and unusual causes. Radiographics. 2015;35:105–122.

- Mayo Clinic. Dysphagia. Available at: mayoclinic.org/diseasesconditions/dysphagia/symptoms-causes/syc-20372028. Accessed July 14, 2018.

- Sura L, Madhavan A, Carnaby G, et al. Dysphagia in the elderly: management and nutritional considerations. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:287–298.

- American Dental Association. Oral Cancer. Available at: mouthhealthy.org/en/az-topics/o/oral-cancer. Accessed July 14, 2018.

- VanderWalde NA, Fleming M, Chera BS. Treatment of older patients with head and neck cancer: a review. Oncologist. 2013;18:568–578.

- Mozzafarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016.

- Popescu SM, Scrieciu M, Mercut V, Tuculina M, Dascălu IN. Hypertensive patients and their management in dentistry. ISRN Hypertension. 2013;Article ID 410740.

- Malamed SF. Handbook of Dental Anesthesia. 6th ed. St Louis: Elsevier Mosby; 2013.

- American Diabetes Association. Statistics About Diabetes. Avaliable at: .diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/statistics. Accessed July 14, 2018.

- Critchlow D. Part 3: Impact of systemic conditions and medications on oral health. Br J Community Nurs. 2017;22:181–190.

- Bagda K, Patel N, Kesharani P, Shah V, Garasia T. Diabetes and oral health. National Journal of Integrated Research In Medicine. 2016;7(6):110–113.

- Chung B. Ask the expert: A1C an important tool in controlling diabetes. Banner Health. 2015;4(1):19.

- Sroussi H, Epstein J, Zumsteg Z, et al. Common oral complications of head and neck cancer radiation therapy: mucositis, infections, saliva change, fibrosis, sensory dysfunctions, dental caries, periodontal disease, and osteoradionecrosis. Cancer Med. 2017;6:2918–2931.

- Mark AM. Oral health concerns for older adults. J Am Dent Assoc. 2016;147:156.

- Stein PS, Aalboe JA, Savage MW, Scott AM. Strategies for communicating with older dental patients. J Am Dent Assoc.2014;145:159–164.

- Harkin H, Kelleher C. Caring for older adults with hearing loss. Nurs Older People. 2011;23:22–28.

- Yellowitz JA, Schneiderman, MT. Elder’s oral health crisis. J Evid Base Dent Pract. 2014;14:191–200.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. August 2018;16(8):41-44.

CHRONIC CONDITIONS

CHRONIC CONDITIONS

Great article! It would be nice to explain “R” reality in the mnemonic “OSCAR”. Is “reality” related to mental health? or living conditions?

Nice post.