Caring for Patients with Oral Cancer

With the rising incidence of human papillomavirus-related oral cancer, dental hygienists must be prepared to help these patients maintain their oral health before, during,

and after radiotherapy treatment.

This course was published in the September 2012 issue and expires September 2015. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the growing incidence of humanpapilloma virus-related oral cancers.

- Identify treatments for head and neck cancers.

- Explain the dental treatment protocols for patients before, during, and after radiotherapy for head and neck cancer.

- Detail palliative care that may help alleviate oral side effects of head and neck cancer treatment.

The next patient on the schedule is Mr. Jones, a 42-year-old white man who has been diagnosed with active human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. Does this fact require special attention during treatment? Yes, because he is at a significantly increased risk of oropharyngeal cancer. The dental hygienist must inquire about any swallowing problems, sore throat, or nodules on his tongue. HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer is typically found at the base of the tongue, in the tonsillar region, soft palate, pharyngeal walls, and in other oropharynx areas.1

Early detection is key to successful treatment. The threat of HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer, which is not related to alcohol or tobacco use, is growing—particularly among white men over the age of 40.2 It is four times more prevalent in men than women.2 With approximately 53,000 new cases diagnosed in 2012,3 HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer can be effectively treated with a variety of therapies, including head and neck radiation. As this cancer becomes more common, many patients who are undergoing head and neck radiation will seek treatment in the traditional private dental practice so dental hygienists need to be well versed in the resultant oral complications.

TREATMENT FOR HEAD AND NECK CANCERS

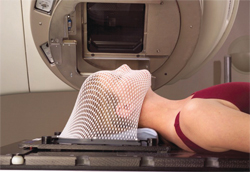

Treatment for head and neck cancer can involve radiation, surgery, chemotherapy, or a combination of these treatments. The purpose of radiotherapy is to shrink tumors or kill cancer cells by damaging their DNA. Internal radiotherapy and external radiotherapy are both used to treat these cancers. Internal radiation therapy, or brachytherapy, disseminates radiation through pins, wires, or other material placed inside the body near the tumor, and is often used in conjunction with external beam radiotherapy. External-beam radiotherapy uses a machine outside of the body to direct localized radiation to the tumor. Radiation doses are measured in grays (Gy). Typically, patients receive external-beam radiation treatments five times a week for 5 weeks to 8 weeks.4 The regimen is individualized to the patient’s disease and treatment needs. External-beam radiation uses different types of radiation systems, such as three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy (3D-CRT) and intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT).4 With these systems, a patient is placed in a machine called a linear accelerator and stabilized by a plastic, mesh type mask to improve target accuracy (Figure 1). IMRT typically spares the major salivary glands from damage.5,6

Radiotherapy, or radiation therapy, though an effective cancer fighter, poses numerous dental challenges during and after treatment.7–9 Because normal cells are also destroyed during the process, nearly all patients suffer from treatment-related oral side effects that may be acute, long-lasting, or develop years after the cancer therapy has been completed.10,11

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE DENTAL TEAM

Prior to the start of radiation treatment, patients should receive professional dental care to improve their oral health because problems, such as inadequate oral hygiene, chipped or broken teeth, failing restorations, and periodontal diseases, can all increase the risk of complications.6,12–15 These patients are also at increased risk of osteoradionecrosis. The dental team can help minimize oral side effects, provide patient education, administer palliative care during treatment, and help patients maintain a healthy oral cavity after treatment is complete. Because few cancer treatment centers include an onsite dental clinic, the private practice dental team must remain up to date on appropriate treatment protocols for this patient population.15

PRIOR TO RADIOTHERAPY

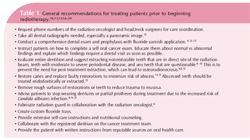

Patients should schedule a dental visit at least 4 weeks prior to beginning radiotherapy. 6,16 Prophylaxis, a head and neck exam, patient-specific oral hygiene instruction, and radiographs should be completed. Dental care is the most important factor in minimizing oral side effects.6,15 Treatment plans should be shared with the patient’s radiation oncologist and head and neck surgeons during all phases of dental care. Table 1 (page 55) lists the steps to follow in treating patients who are scheduled to begin radiotherapy.10,13,14,16–20

CONSIDERATIONS DURING AND AFTER TREATMENT

The intensity and incidence of radiotherapy’s oral effects vary from patient to patient. Some may experience mild xerostomia while others may develop severe xerostomia, dysphagia, dysgeusia, and pain. Because mucositis is almost inevitable in this patient population, palliative recommendations should be provided. Patients should be advised to call their cancer team if they notice an increase in soreness, swelling, or bleeding, or a sticky white film appears in their mouth.17

Dental hygienists are critical during the radiotherapy process because poor dental hygiene and lack of self-care motivation are significant risk factors for oral side effects.15 Poor self-care can cause delays in radiation treatment intervals or stall treatment altogether. Dental hygienists can make a difference in the ultimate outcomes of cancer therapy by educating patients about the possible oral side effects and how to prevent or treat symptoms (Table 2).4,10,11,13–16,18–20 In order to minimize prolonged oral side effects, patients should be scheduled more frequently for recare appointments and should continue performing monthly self oral cancer exams.9,11,14 Frequent recare intervals will ensure that xerostomia can be effectively addressed to prevent dental caries and to discover any infections once treatment is over.

Some side effects manifest months to years after treatment is complete, so more frequent dental visits and thorough oral cancer screenings at each visit are important. Conditions, such as radiation caries and osteoradionecrosis, typically show up within 3 months to a year after treatment—making long-term follow-up care essential.10 Dental hygienists need to emphasize the need for continued, meticulous oral self-care. A post-treatment panoramic film may also be appropriate.6

PROTECTING PATIENTS

With the incidence of HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer rapidly growing, patients undergoing radiotherapy are more likely to be part of the private dental practice’s patient population. Radiotherapy is effective against cancer, but leaves the patient vulnerable to many oral side effects that can diminish quality of life. Oral tissues directly affected by head and neck radiotherapy include the salivary glands, mucosal membranes, jaw muscles, and bone.12 If side effects are extreme, patients may not be able to continue with their treatment. The dental team plays a crucial role in preventing, minimizing, and managing the oral side effects of radiotherapy in order to preserve dental health and contribute to successful treatment.

The Dental Provider’s Oncology Pocket Guide and Oncology Pocket Guide to Oral Health from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (www.nidcr.nih.gov) are helpful resources. Two of the most important services provided by dental hygienists are thorough oral cancer screening and patient education on self oral cancer exams. Completing these two tasks at every dental appointment can save a life or eliminate the need for more aggressive treatments on already compromised patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Ann McCunniff, MD; Chris Gibson, MPH, RT(R)(T); and Sherry Strickland, BS, RT(T); for their assistance with this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4294–4301.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human Papillomavirus-Associated Cancers—United States, 2004-2008. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ mmwr/preview/ mmwrhtml/ mm6115a2.htm.Accessed August 8, 2012.

- American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO). Radiation Therapy for Head and Neck Cancers. Facts to Help Patients Make an Informed Decision. Pamphlet. Available at: www.rtanswers.com/downloads/ headneck.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2012.

- National Cancer Institute at the National Institute of Health. Radiation Therapy for Cancer. Available at: www.cancer.gov/ cancertopics/ factsheet/ Therapy/radiation. Accessed August 8, 2012.

- Hey J, Setz J, Gerlach R, et al. Parotid gland recoveryafter radiotherapy in the head and neck region–36 months follow-up of a prospective clinical study. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:125.

- Ben-David MA, Diamante M, Radawski JD, et al.Lack of osteoradionecrosis of the mandible after intensity-modulated radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: likely contributions of both dental care and improved dose distributions. In J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:396–402.

- McCaul LK. Oral and dental management for head and neck cancer patients treated by chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Dent Update. 2012;39:135–140.

- Tolentino Ede S, Centurion BS, Ferreira LH, Souza AP, Damante JH, Rubira-Bullen IR. Oral adverse effects of head and neck radiotherapy: literature review and suggestion of a clinical oral care guideline for irradiated patients. J Appl Oral Sci. 2011;19:448–454.

- Walker MP, Wichman B, Cheng A, Costar J, Williams K. Impact of Radiotherapy Dose on Dentition Breakdown in Head and Neck Cancer Patients. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2011;1:142–148.

- Jham BC, Reis PM, Miranda EL, et al. Oral health status of 207 head and neck cancer patients before, during, and after radiotherapy. Clin Oral Invest. 2008;12:19–24.

- Bhide SA, Miah AB, Harrington KJ, Newbold KL, Nutting CM. Radiation-induced Xerostomia: Pathophysiology, Prevention and Treatment. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2009;21:737–744.

- Mainali A, Sumanth KN, Ongole R, Denny C. Dental consultation in patients planned for/undergoing/post radiation for head and neck cancers: A questionnaire-based survey. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:669–672.

- Studer G, Glanzmann C, Studer SP, et al. Risk adapted dental care prior to intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT). Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed.2011;121:216–222.

- Meurman J, Gronroos L. Oral and dental health care of oral cancer patients: hyposalivation, caries and infections. Oral Oncology. 2010;46:464–467.

- Joshi V. Dental treatment planning and management for the mouth cancer patient. Oral Oncology. 2010;46:475–479.

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Oral Complications of Cancer Treatment: What the Dental Team Can Do. Available at: www.nidcr.nih.gov/ OralHealth/ Topics/ Cancer Treatment. Accessed August 8, 2012.

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Three Good Reasons to See a Dentist Before Cancer Treatment. Available at: www.nidcr.nih.gov/ OralHealth/ Topics/ CancerTreatment/ThreeGoodReasons.htm. Accessed August 8, 2012.

- Ngeow WC, Chai WL, Zain RB. Management of radiation therapy- induced mucositis in head and neck cancer patients. Part II: supportive treatments. Oncol Rev. 2008;2:164–182

- Caring 4 Cancer. Taste Changes. Available at: www.caring 4 cancer.com/ go/ cancer/ effects/ lesscommon/ taste-changes.htm. Accessed August 8, 2012.

- Caring 4 Cancer. Altered Sense of Taste and Smell. Available at: www.caring4 cancer.com/go/cancer/ nutrition/ symptom-support/ altered-senseof-taste-and-smell.htm. Accessed August 8, 2012.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2012; 10(9): 54-59.