Treatment Planning for Patients with Scleroderma

Follow these strategies to help patients with scleroderma experience successful dental visits and improve their oral self-care regimens.

This course was published in the September 2012 issue and expires September 2015. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Describe the clinical characteristics of the different types of scleroderma.

- Discuss strategies for appropriate dental hygiene management and care for patients with scleroderma.

- Identify steps to help patients with scleroderma improve their oral self-care regimens.

Scleroderma is a chronic connective tissue disorder characterized by an autoimmune rheumatic condition, excessive collagen deposition, and vascular hyperreactivity and dysfunction. Chronic hardening and thickening of the skin, caused by excessive production and accumulation of collagen, are hallmark features (Figure 1).1 Scleroderma mainly affects women between the ages of 30 and 50.2,3 Clinical characteristics, organ involvement, and rate of progression vary, making diagnosis difficult. Symptoms of scleroderma mimic other autoimmune diseases, such as osteoarthritis, bursitis, and lupus, and some patients suffer for years before an accurate diagnosis is made. While the cause is still unknown, the incidence of scleroderma is increasing. Currently, approximately 20 people out of 1 million are affected, with women outnumbering men four to one.3,4

CLASSIFICATIONS

Scleroderma is divided into two major categories: localized and systemic.4 Localized forms have a gradual onset and are more common in children. Manifestations are limited to the skin, and internal organs are not affected. Regions of the skin become thickened, hard, and discolored and hair loss is experienced in affected areas. Two subclassifications—morphea and linear—are associated with localized scleroderma.4 Of the two types, morphea is more benign and characterized by oval, thickened sclerotic skin patches sometimes accompanied by muscle and joint pain (Figure 2).4 Affected areas of the skin may be purple-brown in color, itchy but painless, and may gradually return to normal. However, the skin can remain affected for years and the discoloration can be disfiguring.

The linear type is characterized by long narrow areas of thickened and abnormally colored skin. The skin changes commonly affect the lower limbs and torso and, to a lesser extent, the arms and face. In severe cases, the tissue beneath the skin may be affected causing a contracture type of deformity that prevents normal movement of the affected area.5 The resulting hand and facial deformities often compromise quality of life.6

Systemic forms of scleroderma (SSc) mainly occur in adults and involve internal organs, blood vessels, and skin. The progressive connective tissue fibrosis that affects the internal organs with SSc is potentially lethal with interstitial lung disease being the leading cause of death.4 Subclassifications of SSc include limited and diffuse. Individuals with either subtype usually present with Raynaud’s

phenomenon—an episodic circulatory disorder—as well. Raynaud’s symptoms often occur for years before the skin tightening of SSc manifests and its onset is often the first symptom of SSc. Raynaud’s phenomenon is characterized by triphasic color change, pain, ulceration, and numbness in the hands and toes in response to cold temperatures, strong emotion, and anxiety.5

The primary clinical sign of limited SSc is thick and tight skin on the fingers caused by excess collagen deposition. This condition results in difficulty bending or straightening the fingers.3 Other manifestations include calcium deposits under the skin, thickened skin patches, edema, and changes in small blood vessels resulting in telangiectasis. Painful tightening of the skin occurs with disease progression.

The skin eventually binds with underlying structures and painful ulcerations occur at the joints. Other symptoms include severe itching related to skin dryness, digital ulcerations, and infection. While rare, organ involvement can occur. Gastrointestinal disturbances and pulmonary hypertension are the most common systemic manifestations occurring with limited SSc.4

Diffuse SSc is associated with extensive and often rapidly progressive skin indurations as well as involvement of multiple internal organ systems. Esophageal dysmotility, renal disease, cardiac dysfunction, and pulmonary disease are common systemic manifestations. The chronic hardening and sclerosis of the connective tissue within these organ systems are life threatening.6

Skin changes often start in the hands as a painless swelling or pitting distal in the extremities. Both sides of the body are typically affected with the hands, fingers, lower arms, and face most commonly impacted. Eventually the skin becomes indurated, smooth, atrophic, and bound to the subcutaneous tissues. 6 Telangiectasia spots also appear, caused by swelling of the small blood vessels, and tendon friction ulcerations are common. As the disease progresses, painful tightening and swelling of the skin occurs and overall range of motion is reduced. Atrophy of the underlying soft tissues and severe fibrosis of the skin, especially in the fingers and hands, result in a clawlike hand deformity.7 Severe skin dryness and itching are common and caused by excess collagen in the skin, which overwhelms the sebaceous and sweat glands in the upper dermis.6 In addition, most individuals with diffuse SSc experience joint and muscle pain.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR DENTAL PROFESSIONALS

Patients with scleroderma are more prone to oral disease, and early treatment interventions are important to prevent systemic complications caused by oral infection.7 Providing professional oral care to this patient population can be challenging. Due to the progressive and debilitating nature of scleroderma, patients may not tolerate much time in the dental chair. As the disease worsens, patients will experience more difficulty opening their mouths. In addition, pharmacological interventions for the disease are complex and often involve immunosuppressive medications and calcium channel blockers. Dental hygienists may want to consult with the patient’s physician prior to treatment to determine if there is a need for premedication and to coordinate overall care.

ORAL MANIFESTATIONS

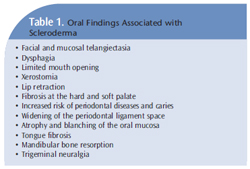

Common oral findings associated with scleroderma are listed in Table 1. The head and neck region is involved in more than 70% of patients with SSc.8–10 Common extraoral findings include narrowing of the eyes, constricted lips, a shrunken nose, and reduced mouth aperture, which causes restricted opening. In addition, radial furrowing around the lips, mottled or diffuse hyperpigmentation, and loss of skin folds around the mouth are often experienced.

Asymptomatic mandibular bone resorption is another common oral finding in patients with scleroderma. The angle of the mandible, condyles, and coronoid process may be affected. The resorption, while not well understood, is most likely linked to facial skin tightening, microvascular involvement of bone vessels, and the underlying taut musculature exerting compression on the mandible.9,10 Areas of mandibular resorption are problematic because they increase the risk of mandibular fractures.10 Regular panoramic radiographs should be taken to screen for oral bone resorption.

Trigeminal neuropathy followed by enlargement of the periodontal ligament (PDL) space are also frequently reported in patients with SSc.11-13 The neuropathy is likely associated with excess collagen accumulation in the perineurium and reduced vascularity to the nerve itself.13,14 The PDL enlargement typically affects all teeth in the dentition and the extent is related to the severity of the disease. The enlargement is often more pronounced on posterior teeth than anterior teeth. The greater masticatory forces exerted on posterior teeth probably accounts for this difference.13 An increase in collagen synthesis with fibrotic thickening of the PDL is most likely related to expansion of the PDL space. Due to salivary gland fibrosis from excess collagen deposition, most patients with SSc experience a high incidence of xerostomia. Loss of quantity and quality of saliva is significant. Denture retention, speech, swallowing, talking, and control of oral disease are all adversely impacted. Medications used to treat scleroderma also exacerbate the salivary gland dysfunction.8,9

Pharmacological options, particularly cholinergic agonist agents that escalate salivary excretion, are recommended. Both pilocarpine and cevmeline hcl are prescription medications that can significantly increase the salivary flow rate in patients experiencing hypofunction.7 Salivary substitutes containing carboxymethylcellulose, calcium, phosphorous, and fluoride can relieve the discomfort of salivary gland dysfunction by lubricating the oral mucosa. These over-the-counter products temporarily increase oral lubrication, reduce enamel solubility, and remineralize the surface. Recommending xylitol gum and mints may also help, although some patients with SSc may find gum chewing difficult. The use of a daily 1.1% sodium fluoride prescription mouthrinse or a 4% sodium fluoride brush-on gel is important to reduce caries risk. Frequent application of fluoride varnish should be considered because the small applicator brush is conducive to accessing the limited opening of the oral cavity typically seen in patients with SSc. Esophageal dysmotility caused by vascular changes and fibrosis often leads to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in SSc patients.9 The highly acidic oral environment created by GERD predisposes patients to perimylolysis erosion and caries. Patients should avoid toothbrushing for at least 30 minutes after an acid reflux experience to minimize acid damage to the enamel. Recommending calcium phosphate technologies and fluoride therapies is key to offsetting chemical damage and strengthening the enamel.

PATIENT MANAGEMENT

Treatment interventions will be more complicated and may take more time for patients with scleroderma. The immobility and rigidity of the skin affects patients’ hands and oral facial structures, which can interfere with their ability to perform self-care, affect movement, and increase the risk of oral disease.15,16 Many of the oral problems experienced in this population result from reduced oral access due to loss of elasticity and subsequent tightening and retraction of the lips and checks.

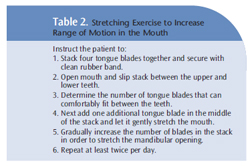

Simple stretching exercises of the mouth (Table 2), as well as the hands, can improve the lower jaw’s range of motion in patients with SSc.17,18 Specific devices designed to improve oral motion and function are also helpful. These appliances use repetitive passive motion and stretching to improve movement and flexibility of the jaw musculature and connective tissues. Some patients may also need physical and occupational rehabilitation.

Many patients with SSc will struggle to keep their mouths open long enough to receive dental hygiene care. A mild analgesic taken 1 hour before the appointment may make patients more comfortable. Air polishing and ultrasonic scaling are often contraindicated due to hard and soft palate fibrosis.7 Patients with scleroderma should be semireclined to prevent pooling of saliva, which can increase the risk of choking or aspiration.

Scheduling patients during periods of the day when they feel best can facilitate more successful dental hygiene interventions. Shorter appointment times may decrease oral stress caused by limited facial movement. Often, a dental assistant will be needed to retract the tongue and assist with high speed suction. A mouth prop will also help gain access and assist the patient in keeping his or her mouth open.7

During local anesthetic administration, clinicians may find tissues harder to penetrate, and injections may be more uncomfortable for the patient. Anesthetic agents without epinephrine should be used because epinephrine can exacerbate the microangiopathy disease commonly found in patients with SSc.8 Taking radiographs of patients with scleroderma-induced microstomia can be problematic. Size one or size zero film or sensors should be used and only a few radiographs should be exposed per visit. Because of the extreme dryness experienced by many patients with SSc, a room humidifier in the treatment area may be beneficial.7 The humidifier may keep tissues hydrated, easing skin tension as well as improving movement of tight skin. To control oral infection, frequent recare is advisable.8 Patients with SSc often consume a soft, high-carbohydrate diet because of their dysphagia. This diet combined with challenges in performing effective self-care greatly increases the risk of caries. Patients on calcium channel blockers will need to be frequently monitored for signs of gingival overgrowth. As such, recare should be scheduled for every 2 months to 3 months.

Since most patients with scleroderma also have Raynaud’s phenomenon, where the small blood vessels of the hands contract in response to cold or anxiety, dental hygienists may want to increase room temperature and keep a blanket and gloves or hand warmer available. As stress may exacerbate Raynaud’s symptoms, some patients may benefit from the use of anti-anxiety medications and other stress relievers, such as soothing music, effective pain management, and facilitative guidance, during the appointment.

ORAL SELF-CARE

Problems with self-care, altered capillary vascularization, poor diet, and salivary hypofunction contribute to increased oral disease among patients with scleroderma. Fatigue, pain, and depression also are common symptoms that may affect patients’ ability to perform oral self-care. Dental hygienists need to work with patients to find ways to improve oral self-care while also remaining realistic about expectations.7 Enlarging or extending the toothbrush handle may improve toothbrushing technique. Powered toothbrushes and flossing devices may promote optimal oral hygiene, although some patients may find fitting the device in the mouth difficult because of their restricted opening. Others may have problems holding the device due to their limited hand strength. The use of a pediatric toothbrush may improve access. Patients with scleroderma often experience lip and gingival retraction on the buccal side of the teeth, eliminating the ability to brush even with a pediatric brush, so an end tuft brush may be better.

Flossing is problematic for patients with scleroderma.7 The use of finger cots, which act as rubber thimbles, may help these patients improve their oral cleaning capability. Self-care education should be focused on alternative interproximal self-care aids and flossing devices that are handheld or powered. In addition, teflon-coated floss may be too slippery for some individuals with scleroderma. Dental tape may be easier to grasp. Consultation with an occupational therapist can help patients overcome obstacles in performing self-care and finding adaptive devices that can facilitate effective self-care.

Tobacco cessation is critical for SSc patients because tobacco use increases vascular changes and hyperkeratosis, complicating scleroderma symptoms as well as increasing periodontal disease risk.8 Patients should be reminded to avoid alcohol, excessive intake of caffeine, and secondhand smoke because they cause peripheral vasoconstriction and contribute to xerostomia. Patients with scleroderma face many challenges in achieving and maintaining oral health. Through consultation with patients and adapting treatment techniques, dental hygienists can help this population successfully receive professional dental care, in addition to facilitating strategies to improve their self-care regimens.

REFERENCES

- National Institutes of Health, US Department ofHealth and Human Services. Scleroderma. Bethesda,Md: National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletaland Skin Diseases; 2006. NIH publication 06-4271.

- Nikpour M, Stevens WM, Herrick AL, Proudman SM.Epidemiology of systemic sclerosis. Best Pract Res ClinRheumatol. 2010;24:857–869.

- Thompson AE, Pope JE. Increased prevalence ofscleroderma in southwestern Ontario: a clusteranalysis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:1867–1873.

- Atzeni F, Bardoni A, Cutolo M, et al. Localized andsystemic forms of scleroderma in adults. Clin ExpRheumatol. 2006;24:36–45.

- Scholand MB, Carr E, Frech T, Hatton N, MarkewitzB, Sawitzke A. Interstitial lung disease in systemicsclerosis: diagnosis and management. Rheumatology.2012;S1:008.

- Joachim G, Acorn S. Life with a rare chronic disease:the scleroderma experience. J Adv Nurs.2003;42:598–606.

- Tolle SL. Scleroderma: considerations for dentalhygienists. Int J Dent Hyg. 2008;6:77–83.

- Alantar A, Cabane J, Hachulla E, et al.Recommendations for the care of oral involvement inpatients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Care Res.2011,63:1126–1133.

- Albilia JB, Lam DK, Blanas N, Clokie CM, Sándor GK.Small mouths…big problems? A review ofscleroderma and its oral health implications. J CanDent Assoc. 2007;73:831–836.

- Leung WK, Chu CH, Mok MY, Yeung KW, Ng SK.Periodontal status of adults with systemic sclerosis:case-control study. J Periodontol. 2011;82:1140–1145.

- Mehra A, Kumar S. Periodontal manifestations insystemic sclerosis: a review. Dent Today. 2008;27:50–54.

- Alpoz E, Cankaya H, Guneri P. Facial subcutaneouscalcinosis and mandibular resorption in systemicsclerosis: a case report. Dentomaxillofac Radiol.2007;36:172–174.

- Auluck A. Widening of periodontal ligament spaceand mandibular resorption in patients with systemicsclerosis. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2007;36:441–442.

- Anbiaee N, Tafakhori Z. Early diagnosis ofprogressive systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) from apanoramic view: report of three cases. DentomaxillofacRadiol. 2011;40:457–462.

- Fischoff D, Sirois D. Painful trigeminal neuropathycaused by severe mandibular resorption and nervecompression in a patient with systemic sclerosis: casereport and literature review. Oral Surg Oral Med OralPathol Oral Radiol. 2000;90:456–459.

- Poole JL, Brewer C, Rossie K, Good CC, Conte C,Steen V. Factors related to oral hygiene in persons withscleroderma. Int J Dent Hyg. 2005;3:13–17.

- Pizzo G, Scardina G, Messina P. Effects of anonsurgical exercise program on the decreased mouthopening in patients with systemic scleroderma. ClinOral Investig. 2003;7:175–178.

- Mugii N, Hasegawa M, Matsushita T, et al. Theefficacy of self-administered stretching for finger jointmotion in Japanese patients with systemic sclerosis.J Rheumatol. 2006;33:1586–1592.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2012; 10(9): 50-53.