SCYTHER5/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

SCYTHER5/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Vaccination Recommendations

Dental hygienists need to be familiar with vaccination recommendations in order to protect themselves from exposure to infectious diseases and educate patients about the importance of immunizations.

This course was published in the July 2018 issue and July 31, 2021. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify vaccination recommendations for health care professionals.

- Discuss the role of the dental hygienist in ensuring the dental team is appropriately vaccinated.

- Provide resources to patients on ensuring they receive appropriate vaccinations to maintain health.

HEPATITIS B VIRUS

Infection with the hepatitis B virus can lead to lifelong chronic infection and serious liver damage.1 Health care professionals are in frequent contact with blood, saliva, and other bodily fluids that increase their risk of hepatitis B virus exposure either through percutaneous (puncture through the skin) or mucosal exposure (direct contact with mucous membranes). The hepatitis B vaccination is the most effective measure of prevention.2–4As part of standard precautions and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA) Bloodborne Pathogens Standard, employers are required to make hepatitis B vaccination available to all employees who may come in contact with blood or other potentially infectious material.5

The hepatitis B vaccination is recommended for all health care professionals.3,5,6 For unvaccinated individuals, or if no proof of vaccination is available, a three-dose series (0-, 1-, and 6-month schedule) of hepatitis B vaccines is administered. Testing for antibodies against hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg) is recommended 1 month to 2 months after the third dose to evaluate the response to the vaccination. The three-dose vaccine series produces a protective antibody response in more than 90% of healthy adults younger than 40. Completely vaccinated health care professionals with anti-HBsAg less than 10 mIU/mL should receive an additional dose of hepatitis B vaccine, followed by additional HBsAg testing 1 month to 2 months later. This additional dose is referred to as a challenge dose or booster to provide rapid protective immunity against infection. The challenge dose may be used to determine the presence of vaccine-induced immunologic memory through the generation of an anamnestic response (renewed rapid production of an antibody on the second or subsequent encounter with the same antigen). Health care professionals whose anti-HBsAg levels remain less than 10 mIU/mL should complete the second series (usually six doses total), and anti-HBsAg testing should be done 1 month to 2 months after the final dose.

If no antibody response occurs after six doses of the vaccination, testing for HBsAg is strongly recommended. If HBsAg-negative, health care professionals will be counseled about precautions to prevent hepatitis B virus infection and the need to obtain hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) prophylaxis for any known or probable parenteral exposure to HBsAg-positive blood. HBIG can increase protection until a response to vaccination is obtained. HBIG administered alone is the primary means of protection after a hepatitis B virus exposure. HBIG provides passively acquired anti-HBs and temporary protection for 3 months to 6 months. Passively acquired anti-HBs can be detected for 4 months to 6 months after administration of HBIG. If HBsAg-positive, health care professionals will be referred for post-exposure evaluation/follow-up and counseled about the need for work restrictions to prevent the transmission of hepatitis B to others.

For vaccinated health care professionals with documented anti-HBs ≥10 mIU/mL, there is no need for hepatitis B prophylaxis regardless of the source patient hepatitis B surface antigen status.

If health care professionals decline the hepatitis B vaccination, they should sign a copy of a hepatitis B vaccination declination form and it should be filed in their personnel records.

In November 2017, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the HepB-CpG vaccine for the prevention of hepatitis B in individuals age 18 and older. It offers a two-dose schedule (0, 1 month).7

MEASLES, MUMPS, RUBELLA

Measles is one of the most transmissible vaccine-preventable diseases. Measles does not even require personal contact for transmission. The measles virus causes symptoms that can include fever, cough, runny nose, and red, watery eyes, commonly followed by a rash that covers the whole body. It can lead to ear infections, diarrhea, and pneumonia; however, it rarely causes brain damage or death.8

Herd immunity, in which unimmunized individuals are protected because a large enough percentage of individuals have been vaccinated, can be achieved by 92% to 95% vaccination coverage.9 Suboptimal vaccination rates can lead to regular outbreaks. In recent years, measles outbreaks have occurred in New York, New Jersey, Europe, Africa, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Japan. In 2015, a large multistate outbreak was linked to Disneyland in Anaheim, California, and started from a traveler who became infected overseas and then visited the park. Scientists at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed this measles outbreak was the identical virus strain genotype that caused the largest measles outbreak in the Philippines in 2014. The majority of those infected with the virus were unvaccinated at the time.10,11

Mumps is a viral disease whose main target is the parotid salivary gland, and can cause complications, such as encephalitis, meningitis, orchitis (inflammation of the testicles), oophoritis (inflammation of the ovaries), deafness, and pancreatitis, but death is rare.2,8 The mumps virus causes fever, headache, muscle aches, tiredness, loss of appetite, and swollen and tender salivary glands under the ears on one or both sides. The herd immunity threshold for mumps is about 90%. Though the disease is no longer common in the developed world, mumps outbreaks still occur in the US, especially in areas of close contact, such as schools, colleges, and camps.10

Rubella (also known as German measles) is a mild infection in children but can be serious in pregnant women due to the risk of congenital infection. The rubella virus causes fever, sore throat, rash, headache, and eye irritation. In up to half of adolescent and adult women, rubella causes arthritis. If a woman gets rubella while she is pregnant, she could have a miscarriage, or her baby could be born with serious birth defects.8 To prevent outbreaks, at least 85% of the population should be immune to rubella.

Measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) are highly contagious viral infections. Compared with the general population, health care professionals have a greater risk of acquiring measles due to its highly contagious nature and its ability to persist in aerosol suspension for at least 1 hour. Transmission from patients to unprotected health care professionals can occur via infected individuals who seek professional care before developing clinically recognizable disease. Additionally, susceptible health care professionals may expose colleagues and patients to increased risk.6

The MMR vaccine contains weakened versions of live MMR viruses. The vaccine works by triggering the immune system to produce antibodies against MMR. The MMR vaccination is recommended for all health care professionals in the US. The World Health Organization has not provided any specific recommendations or evidence of measles immunity in health care professionals. Currently accepted proof of immunity includes documented administration of two MMR vaccine doses separated by at least 28 days, laboratory evidence of immunity, and laboratory confirmation of disease.6,12 In the US, one or two doses of MMR vaccine are recommended for all unvaccinated health care professionals without laboratory-confirmed disease or immunity against MMR during nosocomial outbreaks.3

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends that all health care professionals born during or after 1957 have adequate presumptive evidence of immunity to MMR if documentation of two doses of measles and mumps vaccine and at least one dose of rubella vaccine, laboratory evidence of immunity, or laboratory confirmation of disease. Further, the ACIP recommends that health care facilities should consider vaccination of all unvaccinated health care personnel who were born before 1957 and who lack laboratory evidence of MMR immunity or laboratory confirmation of disease. In October 2017, the ACIP recommended that at-risk individuals previously vaccinated with two doses of a mumps-virus containing vaccine should receive a third dose of a mumps- virus-containing vaccine to raise protection.2

PERTUSSIS, TETANUS, DIPHTHERIA

Pertussis or whooping cough is a highly-transmissible respiratory disease. It causes severe coughing spells, which can lead to difficulty breathing, vomiting, disturbed sleep, weight loss, incontinence, and rib fractures.2 Health care professionals are at increased risk for acquiring pertussis infection if in contact with infected patients and waning protection from either childhood pertussis vaccination or prior pertussis infection. Infected health care professionals can serve as sources of infection for susceptible contacts including patients, other clinicians, and family members.

Tetanus is caused by the bacterium Clostridium tetani. Tetanus enters the body through cuts, scratches, or wounds. Contamination of wounds with tetanus spores in unimmunized persons can evoke illness with muscle spasms and sometimes death. It causes painful muscle tightening and stiffness usually all over the body. Tetanus, or lockjaw, prevents an individual from opening his or her mouth, swallowing, and sometimes from breathing due to tightening of muscles in the head and neck region.13 To maintain immunity, periodic boosters in adulthood are required. Reported tetanus cases continues to be low in the US.13

Diphtheria usually produces respiratory symptoms or it can affect other organs and can cause death. A thick coating is formed in the back of the throat leading to breathing problems, heart failure, paralysis, or death. Cases are rarely seen in the US.13

Generally, vaccination offers the best protection against pertussis infection. In 2006, the ACIP recommended that health care professionals ages 19 to 64 receive a single dose of the tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) to reduce the risk of transmission of pertussis in health care institutions. In 2010, the ACIP indicated that all health care professionals, regardless of age should receive a single dose of Tdap as soon as possible if they had not previously received Tdap.14 Another vaccine called Td protects against tetanus and diphtheria, but not pertussis. A Td booster should be given every 10 years. Tdap may be given as one of these boosters if the individual has never gotten Tdap before. Tdap may also be given after a severe cut or burn to prevent tetanus infection. The ACIP currently recommends that adults receive an initial dose of the Tdap vaccine, with a Td booster every 10 years.10,15 Protective antibody titers have been defined and validated as a correlation of protection against tetanus and diphtheria.

![]() VARICELLA

VARICELLA

Varicella, or chickenpox, is caused by varicella zoster virus (VZV), which is a herpes virus. It is a highly contagious disease that is spread by contact with respiratory droplets and/or vesicle fluid. It is usually self-limited but may cause severe complications such as lower respiratory tract infection, skin and soft tissue infection, or even death.16,17 VZV is responsible for chickenpox in primary infections, which occur mostly in children, teenagers, and young adults. Infection during childhood induces long-lasting immunity. For herpes zoster, the VZV reactivates after a latent period in sensory nerve ganglia and occurs generally in older people.2 In 1996, two doses of varicella vaccine administered 4 weeks to 8 weeks apart were recommended for susceptible adults, including health care professionals. However, seroconversion to vaccination may not ideally correlate with protection, as vaccine-induced antibody titers can decline or disappear over time.18 Vaccination has greatly reduced varicella incidence, resulting in declines in varicella exposures in health care settings. Nevertheless, VZV exposures still occur particularly from herpes zoster cases. Once infected, health care professionals may transmit infection to coworkers and patients. Therefore, it is important to vaccinate health care professionals against varicella. Documentation of VZV immunoglobulin G status of all health care professionals and the vaccination of susceptible clinicians is suggested for effective prevention of nosocomial varicella.10 Until 2017, the ACIP recommended that adults receive a herpes zoster or shingles vaccination for individuals age 60 and older.15 In October 2017, the FDA approved a new recombinant, adjuvenated vaccine for the prevention of herpes zoster in adults aged 50 and older. It is a two-dose schedule (2 months to 6 months apart).19

INFLUENZA

Influenza is an infectious disease caused by an influenza virus that can affect humans, as well as birds, pigs, and chickens.2 The virus mutates quickly, and its seasonal strains cause outbreaks mostly during the winter. The virus infects the nose, throat, and sometimes the lungs, causing fever and musculoskeletal pain. It can cause mild to severe illness and may lead to death.20 Most experts believe that flu viruses are spread mainly by tiny droplets created when people with the flu cough, sneeze, or converse. These droplets can land in the mouth or nose of those who are nearby. Individuals can also get the flu by touching surfaces or inanimate objects that have the active virus on them and then touching their own mouths, nose, or possibly eyes.

Seasonal flu vaccines are designed to protect against infection and illness. How well the flu vaccine works or its ability to prevent flu illness can range widely. The vaccine’s effectiveness can also vary depending on who is being vaccinated.20 Research assessing the benefits and risks of the flu vaccine in both health care professionals and their patients support the vaccine effectiveness and efficacy; thus, the ACIP recommends that all health care professionals and those in training receive an annual vaccination.3,4,10,21Unimmunized health care professionals can act as an infection source for patients, potentially leading to nosocomial influenza outbreaks.22 Vaccination of health care professionals has been associated with reduced work absenteeism and fewer deaths among nursing home patients and elderly hospitalized patients. The ACIP also recommends that adults receive an annual seasonal influenza vaccination.15

ROLE OF THE DENTAL HYGIENIST

Dental hygienists play a key role in the immunization process at two levels. As members of the dental team, they can develop and implement office protocols regarding the appropriate vaccinations. Once an office policy is implemented, dental hygienists can assist with the ongoing monitoring and documentation process.23

Dental hygienists are also integral to patient education. As dental hygienists can practice in a variety of settings, such as schools, public health clinics, dental service organizations, correctional facilities, nursing homes, and private practice settings, they are able to educate the public on the importance of immunizations. Incorporating questions on the health history that identifies a patient’s knowledge regarding his/her vaccination status can open a dialogue between the patient and the dental hygienist. General questions can be added to the health history form regarding the patient’s vaccination status, including past history and/or exposure.

Dental hygienists can emphasize the importance of immunizations to patients. As part of the interprofessional team, the dental hygienist is responsible for identifying a patient’s risk factors based on age, health status, pregnancy status, and type of work environment, as well as individuals traveling outside of the US.21

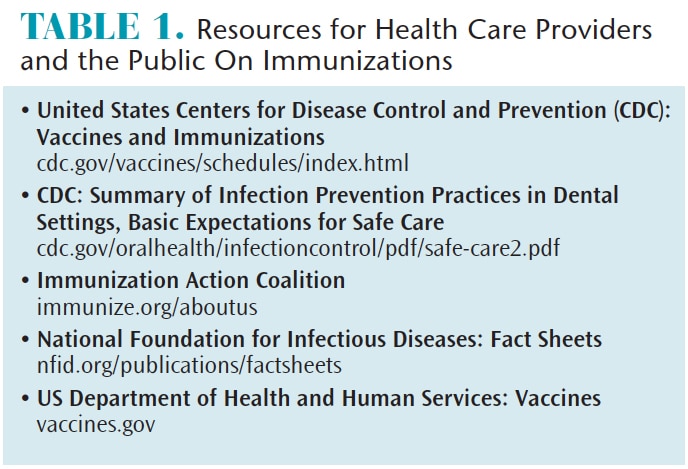

As the infection prevention coordinator, the dental hygienist should be knowledgeable on the most current vaccination protocols as outlined by the CDC, including policies and documentation of vaccinations. Table 1 lists helpful resources for health care professionals and the public regarding immunization recommendations.

SUMMARY

Vaccines are continuously being developed, monitored, evaluated, and revised through recommendations provided by the ACIP. Health care professionals need to be familiar with these ongoing changes to protect themselves from exposure to infectious diseases and educate their patients about the importance of immunizations. As health care continues to move toward an interprofessional approach, the oral health professional has the potential to be instrumental in improving public health outcomes.

REFERENCES

- Cohen C, Caballero J, Martin M, et al. Eradication of hepatitis B: A nationwide community coalition approach to improving vaccinations, screening, and linkage to care. J Community Health. 2013;38:799–804.

- Haviari S, Benet T, Saadatian-Elahi M, et al. Vaccination of healthcare workers: a review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11:2522–2537.

- Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on immunization practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(RR-1):1–31.

- Abara WE, Qaseem A, Schillie S, et al. Hepatitis B vaccination, screening, and linkage to care: Best practice advice from the American College of Physicians and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ann Int Med. 2017;167:794–804.

- Guidelines for infection control in dental healthcare settings—2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(RR17);1–61.

- New York State Department of Health. Health Advisory: Recommendations for Vaccinations of Health Care Personnel Available at: health.ny.gov/prevention/immunization/toolkits/docs/health_advisory.pdf Accessed June 19, 2018.

- Schillie S, Harris A, Link-Gelles R, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for the use of a hepatitis B vaccine with a novel adjuvant. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:455-458.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles, Mumps, and Rubella. Available at: cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/visstatements/mmr.html. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- Brever NT, Moss JL. Herd immunity and the herd severity effect. Lancer Infec Dis. 2011;15:868–869.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mumps Cases and Outbreaks. Available at: cdc.gov/mumps/outbreaks.html. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- Zipprich J, Winter K, Hacker J, et al. Measles outbreak—California, December 2017–February 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:153–154.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Routine Measles, Mumps, and Rubella Vaccination. Available at: cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/mmr/hcp/recommendations.html Accessed June 19, 2018.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tdap (Tetanus, Diphtheria, Pertussis. Available at: cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/visstatements/tdap.html. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- Lu PJ, Graitor SB, O’Halloran A, et al. Tetanus, diphtheria and acellular pertussis (tdap) vaccination among healthcare personnel—United States, 2011. Vaccine. 2014;32:572–578.

- La EM, Trantham L, Kurosky SK, et al. An analysis of factors associated with influenza, pneumococcal, tdap, and herpes zoster vaccine uptake in the US adult population and corresponding inter-state variability. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14:430–441.

- Dooling KL, Guo A, Patel M, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of herpes zoster vaccines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:103–108,

- Wu MF, Yang YW, Lin WY, et al. Varicella zoster virus infection among healthcare workers in Taiwan: seroprevalence and predictive value of history of varicella infection. J Hosp Infect. 2012;80:162–167.

- Behrman A, Lopez AS, Chaves SS, et al. Varicella immunity in vaccinated healthcare workers. J Clin Viro. 2013;57:109–114.

- Dooling KL, Guo A, Patel M, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of herpes zoster vaccines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:103–108.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccine Effectiveness—How Well Does the Flu Vaccine Work? Available at: cdc.gov/flu/about/qa/vaccineeffect.htm. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Immunization: the Basics. Available at: cdc.gov/vaccines/index.html. Accessed: June 19, 2018.

- Hagemeister MH, Stock NK, Lydwig T, et al. Self-reported influenza vaccination rates and attitudes towards vaccination among health care workers: Results of a survey in a German university hospital. Public Health. 2018;154:102–109.

- Giblin L. Exposure control: barriers for patient and clinician. In: Wilkins EM, Wyche CJ, Boyd LD, eds. Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 12th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2016.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. July 2018;16(7):32–34,37.

VARICELLA

VARICELLA