LINA MOISEIENKO/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

LINA MOISEIENKO/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

A Guide to Water Fluoridation

Examining fluoride intake at an individual patient level is necessary to develop effective caries management plans.

This course was published in the July 2018 issue and July 31, 2021. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the optimal level of fluoride in community water fluoridation.

- Describe fluoride’s mechanism of action.

- Discuss the history of community water fluoridation.

- Explain the role of oral health professionals in caries risk prevention.

Water fluoridation is the adjustment of the naturally occurring fluoride found in water to a level known to prevent tooth decay.1 Exposure to small amounts of fluoride over time reduces the incidence of tooth decay by enhancing remineralization and inhibiting demineralization of tooth enamel.2–4 Fluoride’s action in preventing tooth decay results in fewer restorations and dental extractions, as well as in reduced pain and suffering often associated with tooth decay.

Many public health agencies and professional health organizations have advocated for the addition of a small amount of fluoride to drinking water to prevent dental caries. Although the practice of adjusting the level of fluoride in the water has been controversial, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), American Medical Association, American Dental Association, American Academy of Pediatrics, and many others have recommended water fluoridation as an effective means to promote oral health.2

While the unproven allegations surrounding water fluoridation, such as cancer risk, lower IQ, bone fractures, and Alzheimer’s disease, have remained constant, the approaches to generating controversy have varied.2 These include the distribution of fluoride misinformation via the internet, local newspapers, or other settings, including health food stores, chiropractic offices, and places of worship. Systematic reviews of the world literature, however, support the use of optimally fluoridated water at 1 ppm as safe with no adverse health effects.1–5 The totality of the scientific evidence gathered thus far does not support a direct link between the currently recommended levels of fluoride intake and any of the health conditions listed above. Further research is recommended and is likely to focus on fluoride metabolism, fluoride as it relates to human genetics, and refinement of the optimal range of total fluoride intake.4Therefore, oral health professionals should continue to monitor dental research regarding fluoride and water fluoridation as it relates to caries management.

HOW FLUORIDE WORKS

Drinking fluoridated water provides both a systemic and topical application of fluoride.5,6 After drinking a glass of fluoridated water, most of the fluoride is absorbed from the stomach and the small intestine into the blood.2 The fluoride blood levels reach a peak concentration within 20 minutes to 60 minutes and decline over the next 3 hours to 6 hours, as fluoride is absorbed by calcified tissues and removed from the body by the kidneys.2

Current research indicates that caries prevention from fluoridated water is primarily the result of the topical contact of fluoride with teeth.4 Fluoridated water surrounds teeth with a constant supply of low levels of fluoride and provides a reservoir of fluoride available for tooth surface remineralization. Individuals consuming 1 L of fluoridated water at 0.7 mg/L receive 0.7 mg of fluoride.2 Drinking optimally fluoridated water reduces tooth decay by approximately 25%.2–4,6–8

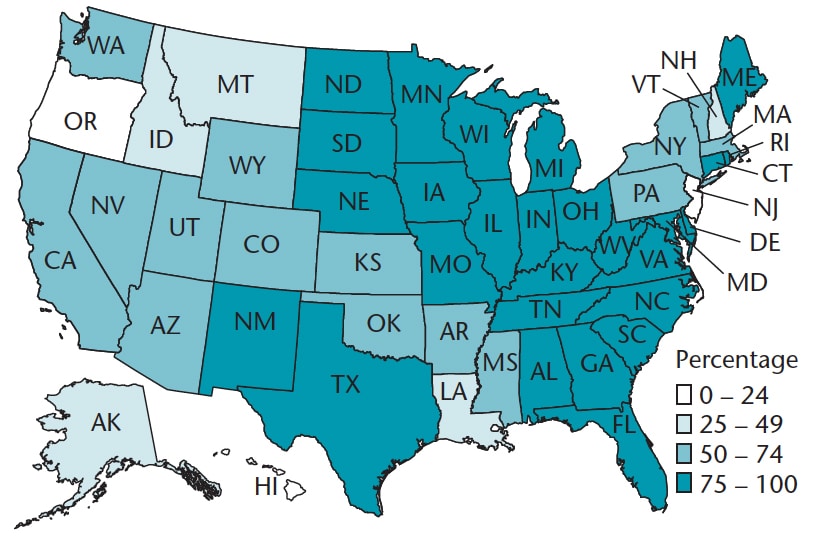

Currently, more than 211 million Americans are served by water systems that provide optimally fluoridated water.1,3 In 2014, approximately 74% of the US population was served by community fluoridated water (Figure 1). Hawaii (11.3%), New Jersey (14.6%), and Oregon (22.6%) have the lowest percentage of people receiving optimally fluoridated water.3 Regions with the highest percentage of people receiving fluoridated water (75% or more) are primarily located in the Southeast, Mid-Atlantic, and Upper Midwest.

The first community in the world to fluoridate its public water system was Grand Rapids, Michigan in 1945.1,3 The study of the Grand Rapids fluoridation experience analyzed the rate of dental caries among approximately 30,000 school children. Results showed that among children born after fluoride was added to the water, there was a 60% reduction in tooth decay.9 This breakthrough in caries prevention was viewed as a watershed moment for dentistry because, for the first-time ever, caries was viewed as a truly preventable disease.

Since that time, community water fluoridation has been recognized as one of the top 10 public health achievements of the 20th century because of its contribution to disease prevention.3 Research clearly demonstrates that adults have benefited from community water fluoridation. The average number of caries-infected teeth has decreased from 18 per person in the 1960s to 10 per person in 1999 to 2004.1 Water fluoridation also benefits children, as evidenced by the decrease of caries in at least one permanent tooth per child from 90% of those age 12 to 17 in the 1960s to 60% of those age 12 to 17 in 1999 to 2004.1 Nevertheless, dental caries remains a significant disease, especially for underserved and low-income populations. Approximately 25% of children age 5 to 19 from low-income families have untreated caries.10 Untreated tooth decay continues to increase in adulthood, with 47% of low-income adults age 20 to 44 having untreated caries.10 Moreover, approximately 2 million people in the US annually turn to the hospital emergency department (ED) for their dental needs.11 The primary diagnosis for 42% of all dental-related ED visits in the US is untreated caries.12

ORAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

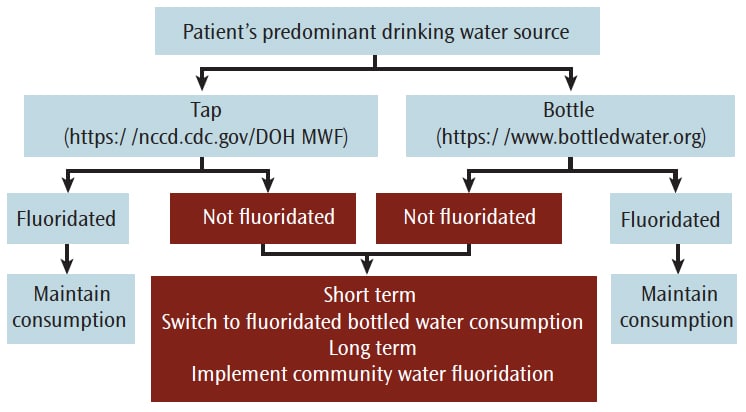

Oral health professionals can play a significant role in caries management by simply determining if patients are drinking fluoridated water and identifying the role fluoridated water can play in caries management. Research indicates the percentage of dental patients who receive information from their oral health professional regarding water fluoridation is only 20%.13 This lack of promotion of such an important disease prevention measure is often due to a lack of awareness.13 Many oral health professionals note that patients do not ask about water fluoridation, so they do not discuss it. Others suggest they are not knowledgeable enough about fluoridation or comfortable in responding to patients who may present anti-fluoride arguments.13 The drinking water flow chart (Figure 2) provides a framework to determine the primary source of a patient’s drinking water. Once the source of a patient’s drinking water is determined, additional dialogue regarding appropriate fluoride exposure and caries management can occur.

In addition, research indicates that most oral health professionals focus their prevention efforts on the importance of oral hygiene. While oral hygiene is important, the effect of fluorides on reducing dental decay is at least as impactful, if not more impactful, than simply brushing.13 Brushing with a fluoride toothpaste can reduce dental decay by approximately 20% to 25%.3 Drinking optimally fluoridated water also reduces dental decay by 25%.3,14 Patients with a low risk of developing caries may not need any additional fluoride interventions except to drink optimally fluoridated water and brush with a fluoride toothpaste. Unfortunately, most patients learn about water fluoridation from the media.13 The quality of the fluoride information in the media, on the internet, and in blogs may vary considerably, and in some instances, may be misleading, or simply false.2 Oral health professionals should assist patients in identifying valid, peer-reviewed, scientific information regarding water fluoridation, such as: thecommunityguide.org/findings/dental-caries-cavities-community-water-fluoridation.15

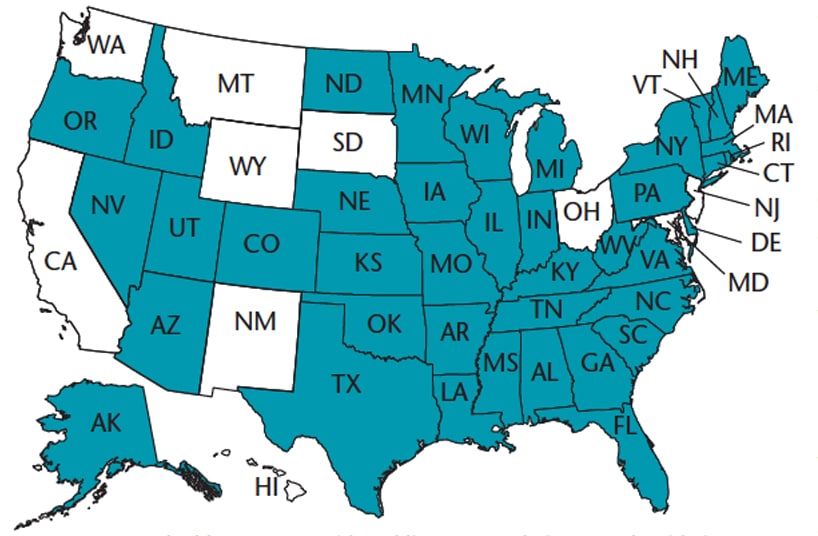

Although three out of four individuals are currently served by fluoridated water systems, research indicates that people are generally unaware of their community water status.13 The US Environmental Protection Agency is the agency responsible for monitoring water quality.2 The national Water Fluoridation Reporting System (WFRS) monitors the fluoride status of 54,000 community water systems.3 Approximately 40 states provide public access to WFRS data online (Figure 3) at: nccd.cdc.gov/doh_mwf/reports/default.aspx. WFRS tracks the communities served, water system type, and the fluoride concentration of the water.3 WFRS also provides information regarding de-fluoridation. If the naturally occurring fluoride in the water happens to be above the recommended level, the local water system operators will de-fluoridate the water to the recommended level of 0.7 ppm. The WFRS system can provide important information to better serve patient needs.

BOTTLED WATER

In 2016, Americans began drinking more bottled water than soda, according to the Beverage Marketing Corp.16 The shift has been attributed to widespread concerns regarding the negative health effects of drinking sugary beverages. Bottled water is a healthy, but expensive alternative. Drinking bottled water is 2,000 times more expensive than drinking optimally fluoridated tap water.16 The estimated per capita annual cost of providing fluoridated tap water ranges from $0.11 to $4.92 for communities with a population of at least 1,000.10

The US is the largest consumer of bottled water with approximately 13 billion gallons of bottled water sold annually, equating to each person in the US consuming 39 gallons of bottled water annually.17 Some brands of bottled water obtain their water from municipal tap water sources.17 Bottled water generally contains less than optimal levels of fluoride.

Bottled water is regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a packaged food product.2 Specific FDA standards exist for the labeling of bottled water with regard to fluoride content only if fluoride is added during processing. Oral health professionals should ask patients about their source of drinking water and discuss the level of fluoride exposure most appropriate for caries management. Individuals who primarily drink bottled water may be missing the dental caries prevention benefits provided by fluoridated water.

Bottled water is often purified by reverse osmosis, distillation, micro-filtration, or carbon filtration processes which can remove fluoride from the water.17 If patients are using a point-of-use water treatment system for their home, it is best to check with the manufacturer of the individual product to determine if it removes fluoride.2 Fluoridated bottled water is available as an alternative. A more complete list of companies that provide fluoridated bottled water is available at: bottledwater.org/health/fluoride.

FLUOROSIS CONCERNS

Dental fluorosis is the appearance of faint white lines, pitting, or chalky streaks on the teeth of young children who consume too much fluoride, generally from a variety of sources including toothpaste, gels, and mouthrinses.4–8 Ideally, fluoride intake should maximize the prevention of dental caries while minimizing the occurrence of dental fluorosis. Dental fluorosis only occurs during tooth formation when the fluoride intake is excessive.2,4 Most fluorosis is very mild with faint white lines or streaks visible only to oral health professionals under good lighting in the clinic. More noticeable fluorosis, such as rarely occurring mottling, may cause concern about the appearance of the teeth. Dental fluorosis depends on the timing, amount, and duration of the excessive fluoride exposure during early childhood.4 The major sources of fluoride exposure include fluoride toothpaste, fluoride supplements, infant formulas, and fluoridated drinking water.4,5,7 Therefore, monitoring a child’s total fluoride intake, especially during the first 6 years to 8 years (when the permanent maxillary central incisors are forming as tooth buds) is important to minimize the risk of fluorosis.2,18,19

While the methods of fluoride delivery may be intended to have a topical effect, the reality is that fluoride is inadvertently swallowed during brushing. The effect is systemic, as well as topical. Children younger than age 6 have yet to fully develop their swallowing reflex and are more likely to swallow than expectorate excess toothpaste.20 Fluoride ingestion during toothbrushing and the use of fluoride supplements are significant factors in a child’s likelihood of developing dental fluorosis.2,4,20 Fluoride supplements in the form of tablets, drops, or fluoride vitamins have been prescribed in the US for decades in nonfluoridated communities to prevent tooth decay. Supplemental fluoride prescriptions are contraindicated for children who reside in communities with optimally fluoridated water.2,20

Approximately 65% of fluorosis cases in nonfluoridated communities are the result of prescribing supplemental fluoride.2,10 For children raised in fluoridated communities, 68% of fluorosis cases are attributed to the use of toothpaste during the first year of life.10Therefore, oral health professionals need to consult with patients to document the primary source of their drinking water and assess total fluoride intake. In addition, parents should be advised to supervise young children during toothbrushing. Drinking optimally fluoridated water is a minor risk factor for developing fluorosis.20

During pregnancy, fluoride in low concentrations crosses the placenta.20 This exposure is considered minimal and not a reason to avoid fluoridated water. The recommendation of the Oral Health Care During Pregnancy Expert Workgroup is that pregnant women drink fluoridated water (via community water fluoridation), or fluoridated bottled water.21 Once the child is born, breast feeding may provide a small amount of fluoride to the infant from the mother’s milk via her plasma fluoride levels. This exposure, however, is negligible.22 Likewise, most infant formulas that must be mixed with water contain low levels of fluoride.20 Thus, to reduce the risk of mild fluorosis, parents may prefer to use nonfluoridated water or low-level fluoridated water to mix infant formula.10,20 Parents who prefer to use soy-based formulas should be advised that these products may contain higher fluoride concentrations than milk-based formulas.20 Hence, parents may also prefer to use nonfluoridated water when mixing soy-based formula. Additional information regarding infant formula and water fluoridation is available at: cdc.gov/fluoridation/faqs/infant-formula.html.

Once children are 6 months, parents can introduce them to food and drink other than breast milk and infant formula.23 Healthy eating and drinking patterns begin early in life. Toddlers need approximately 2 cups of water daily to cover their fluid needs.23

CONCLUSION

The exposure to fluoride, fluoridated water, and fluoridated dental products has evolved during the past century and will continue to evolve in the future. People may be exposed to higher levels of total fluoride than originally anticipated. Consequently, questions have emerged whether current water fluoridation practices provide the expected beneficial effects while avoiding adverse effects, such as fluorosis. Drinking optimally fluoridated water reduces dental caries in children and adults primarily because of the topical effect of fluoride, which enhances remineralization.

Clinicians should assess a patient’s caries risk status, exposure to water fluoridation, and total fluoride intake to determine the appropriate level of fluoride needed for optimal caries management. Research indicates water fluoridation is safe and effective, and in fact should serve as the cornerstone to most individual caries management plans. For patients at low-risk of caries, drinking fluoridated water and brushing with fluoride toothpaste is sufficient to achieve caries prevention.

Identify methods to help patients prevent periodontal disease.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. July 2018;16(7):38-41.