Update on Monkeypox

Understanding the origins of this viral disease and how it spreads will help oral health professionals advise their patients and prevent its transmission.

This course was published in the October 2022 issue and expires October 2025. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 148

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Describe the etiology and presentation of monkeypox.

- Identify the vaccines available to prevent monkeypox.

- Explain appropriate infection control protocols for the dental setting.

Monkeypox is a viral transmissible disease caused by the monkeypox virus, occurring mostly in Central and Western Africa.1 Endemic to animals in these regions, monkeypox is a member of the Orthopoxvirus genus in the Poxviridae family. The other members include the variola virus, which causes smallpox, the vaccina virus used to help make the smallpox vaccine, and the cowpox virus.2

Monkeypox was first discovered in 1958 with two pox-like disease outbreaks in colonies of monkeys used for research.3 While called “monkeypox,” the exact animal of origin is unknown. African rodents and nonhuman primates, however, may carry the virus and infect people.3 There are two types of monkeypox virus: West African and Central African. The 2022 outbreak is from the West African type and is rarely fatal; more than 99% of people who contract the West African type will survive.4 However, people with weakened immune systems, children younger than 8, people with a history of eczema, and pregnant and nursing women may be more likely to become seriously ill or die.4

The first reported human case of monkeypox was in August 1970 in Bokenda, a remote village in the Democratic Republic of Congo in a 9-month-old child with a suspected case of smallpox.2 Further testing revealed the child had contracted the monkeypox virus. The baby’s parents reported occasionally eating monkeys as a delicacy but could not recall if monkey was eaten prior to the outbreak or if the infant had encountered monkeys. The child was the only one in the family not vaccinated with the smallpox vaccine.

The first known monkeypox virus infection in the United States occurred during the summer of 2003 in the Midwest in prairie dogs infected by rodents imported from Ghana in Western Africa. The rodents consisted of two giant pouched rats, nine dormice, and three rope squirrels. Forty-seven cases were reported in six states: Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Ohio, and Wisconsin. All those infected with the virus came in direct contact with the prairie dogs.5 In 2021, two cases were reported, one case in July and one in November. Both involved Americans who traveled from Nigeria to the US.5

Prior to 2022, all diagnosed cases of monkeypox outside of Africa were related to travel. As of August 12, 2022, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 11,177 confirmed cases in the US.6 The states with the highest number of reported cases are New York, California, and Florida. It is not clear how these individuals were infected, but early data suggest that men who have sex with men are making up a high number of the cases.6 There is no clear link between the cases reported and travel from endemic countries and no link with infected animals.7

Transmission

The monkeypox virus is transmitted to humans during the handling of infected animals or by direct contact with the infected animal’s body fluids or lesions.1 The virus is spread person-to-person through direct contact with the infectious rash, scab, or body fluids. Monkeypox can spread through respiratory droplets during prolonged face-to-face contact, such as those passed during kissing, cuddling, or sex. It is also spread by touching items such as clothes and bed linens that previously touched the infectious rash or bodily fluids of an infected individual. Monkeypox can also be spread from a pregnant woman to her fetus. An individual can contract the disease by being scratched or bitten by an infected animal, as well as by preparing, using products, or eating meat of an infected animal.8

Signs and Symptoms

Infection with monkeypox virus causes swollen lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy). This typically occurs with fever onset, 1 day or 2 days before rash onset, or, rarely, with rash onset. Swelling of the lymph nodes may be in the neck (submandibular and cervical), armpits (axillary), or groin (inguinal) and occur on both sides of the body or just one.9

After infection, an incubation period begins lasting on average 7 days to 14 days but can range from 5 days to 21 days. Infected individuals do not have symptoms and are not contagious during this period.

The development of an early set of symptoms (prodrome) includes fever, malaise, headache, sometimes sore throat and cough, lymphadenopathy, and weakness. The infected individual may sometimes be contagious during this period.

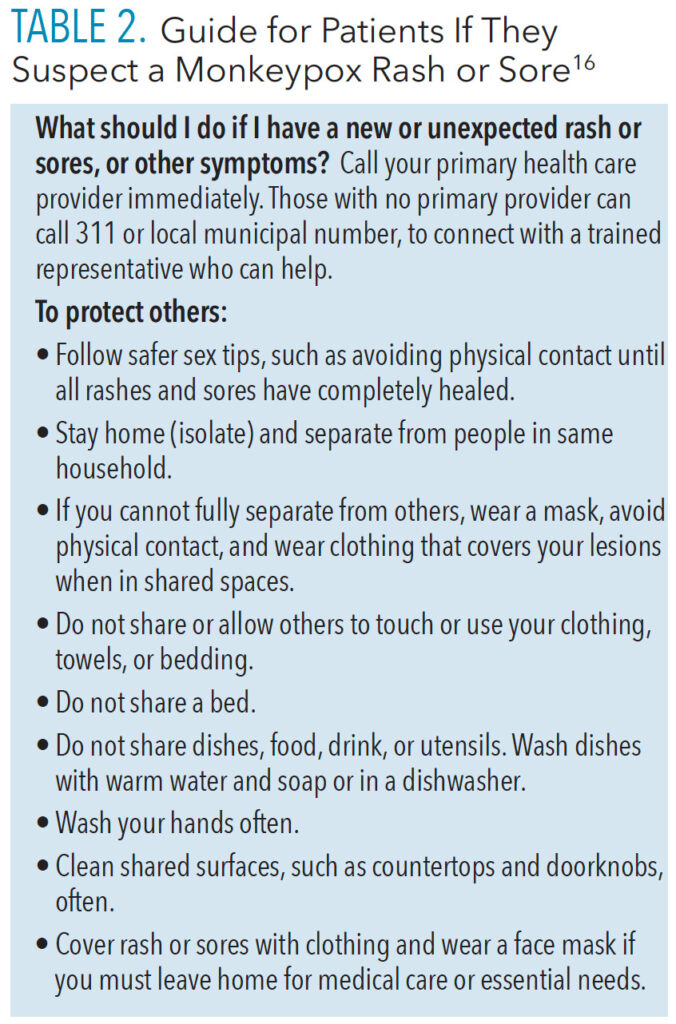

Shortly after the prodrome, a rash appears. Lesions will first develop on the tongue and in the mouth (enanthem stage), and then on the body. They typically develop simultaneously and evolve together on any given part of the body. The evolution of lesions progresses through four stages—macular, papular, vesicular, to pustular—before scabbing over and resolving. This process happens over a period of 2 weeks to 3 weeks. The infected individual is contagious from the onset of the enanthem through the scabbing stage. Pitted scars and/or areas of lighter or darker skin may remain after scabs have fallen off. Once all scabs have fallen off, an individual is no longer contagious.9

Monkeypox lesions are typically well circumscribed, deep seated, and often develop umbilication (Figure 1 [page 28] to Figure 4). They are relatively the same size and same stage of development on a single site of the body. They most commonly present on the face, palms, and soles of the feet. Lesions are often painful until the healing phase—by the end of the second week—when they become itchy and form crusts.9 Table 1 describes the stages of monkeypox in more detail.

Prevention

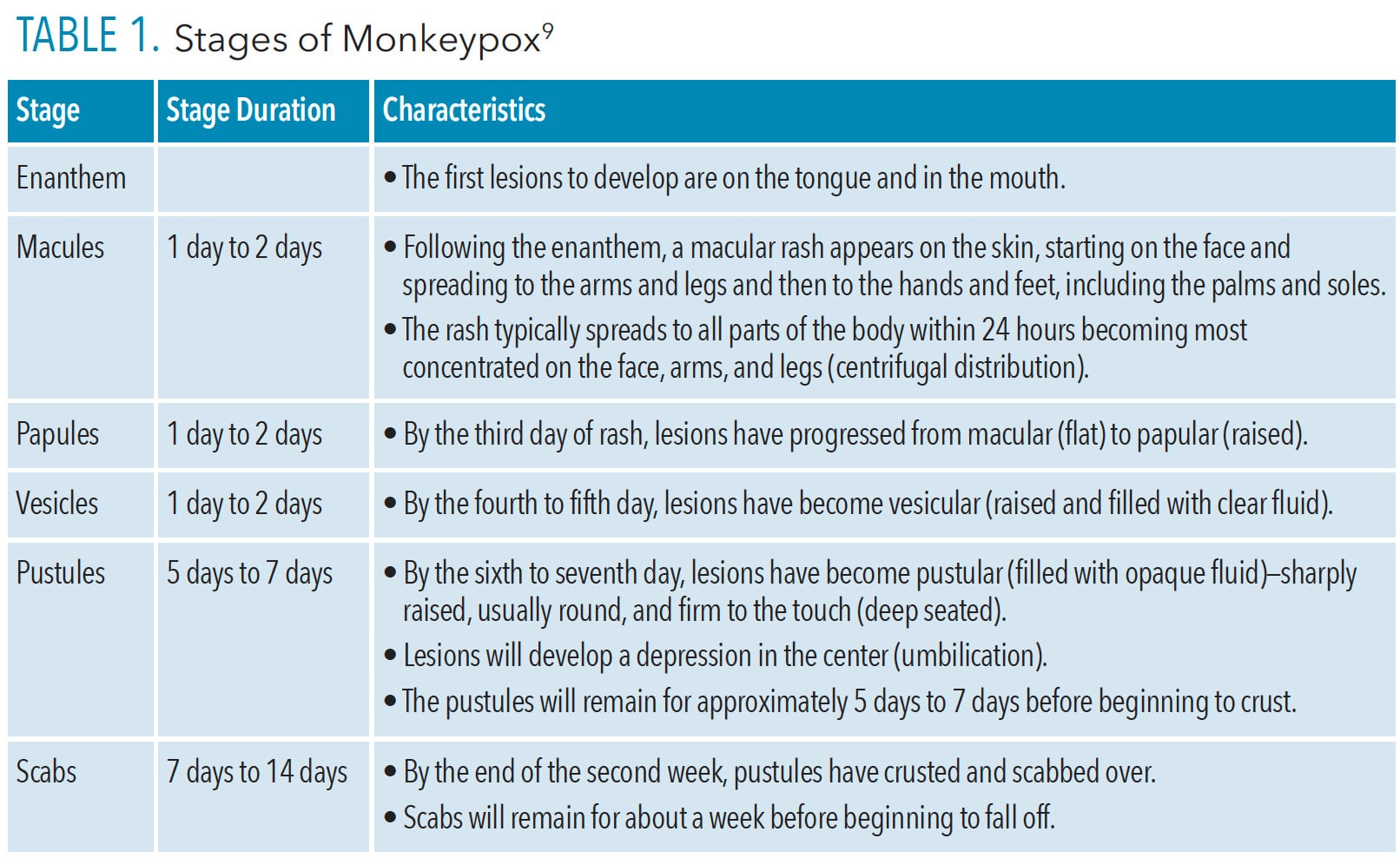

To prevent contracting monkeypox, individuals should avoid contact with an animal infected with the virus. Regularly cleaning hands with soap and water or an alcohol-based hand sanitizer, especially after encountering the individual or animal who is infected, is key. Avoid contact with clothes, bed sheets, towels and other items or surfaces touched with their rash or respiratory secretions of the infected individual. It is important to wash the clothes, towels, bedsheets, and eating utensils with warm water and detergent. Clean and disinfect any contaminated surfaces and dispose of contaminated waste appropriately.10 Healthcare professionals can isolate infected patients from others who could be at risk for infection and should use personal protective equipment (PPE) when caring for patients.11

The current spread of monkeypox is through close, personal, often skin-to-skin contact including sexual activity. The public should understand that the spread of monkeypox may occur at places such as raves, parties, clubs, and festivals. Spaces where minimal or no clothing is worn and where intimate sexual contact occurs also have a higher likelihood of spreading the monkeypox virus.12

Vaccines

Because monkeypox virus is closely related to the virus that causes smallpox, the smallpox vaccine can protect people from getting monkeypox when administered before exposure occurs. Past data from Africa suggest that the smallpox vaccine is at least 85% effective in preventing monkeypox.11

Several vaccines are available to prevent smallpox that also offer some protection against monkeypox. A newer vaccine developed for smallpox (MVA-BN, also known as Imvamune, Imvanex, or JYNNEOS™ was approved in 2019 for preventing monkeypox but is not yet widely available.13 People who have been vaccinated against smallpox in the past will have some protection against monkeypox. The original smallpox vaccines are no longer available, and people younger than 50 are unlikely to have been vaccinated. Smallpox vaccination was ceased in 1980 after smallpox was believed to have been eradicated.13

An antiviral medication developed to treat smallpox (tecovirimat) was approved by the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of monkeypox in January 2022.13 Tecovirimat (also known as TPOXX or ST-246) is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of human smallpox disease caused by the variola virus in adults and children. However, its use for other Orthopoxvirus infections, including monkeypox, is not yet FDA approved.14

ACAM200 and JYNNEOS are the two vaccines approved in the United States to prevent smallpox. In certain groups, such as individuals with serious immune system problems, complications from ACAM2000 can be severe. This vaccine has the potential for more side effects and adverse events than the newer vaccine, JYNNEOS.

ACAM2000 is administered as a live vaccinia virus preparation that is inoculated into the skin by pricking the skin surface. Following a successful inoculation, a lesion will develop at the site of the vaccination (ie, a “take”). The virus growing at the site of this inoculation lesion can be spread to other parts of the body or even to other people. Individuals who receive vaccination with ACAM2000 must take precautions to prevent the spread of the vaccine virus and are considered vaccinated within 28 days.

JYNNEOS is approved by the FDA for the prevention of monkeypox.10 It is administered as a live virus that is nonreplicating; it is administered as two subcutaneous injections 4 weeks apart. There is no visible “take” and, as a result, no risk for spread to other parts of the body or other people. Individuals who receive JYNNEOS are not considered vaccinated until 2 weeks after they receive the second dose of the vaccine.

The CDC recommends that exposed individuals receive the vaccine within 4 days from the date of exposure. If given between 4 days and 14 days after the date of exposure, vaccination may reduce the symptoms of disease, but may not prevent it. The CDC also recommends individuals exposed to monkeypox virus and who have not received the smallpox vaccine within the last 3 years should get vaccinated.11

On June 9, 2022, Germany’s Standing Committee on Vaccination recommended that anyone exposed to monkeypox should receive two doses of the smallpox vaccine Imvanex. Those who have never received a smallpox immunization should receive two doses, 28 days apart, while one dose will suffice for those who have already been vaccinated against smallpox. Due to limited supply, the smallpox vaccine Imvanex should be made available first to people who were exposed to the virus in the previous 14 days. The second priority group is composed of those at increased risk of contracting monkeypox, such as men who have sex with changing male partners as more than 130 monkeypox cases have been diagnosed in Germany among this population.15

Infection Control and Personal Protective Equipment

Infectious and communicable diseases are a continuous occupational risk for oral health professionals and can lead to illness, disability, and loss of work time. Dental practices must maintain the highest level of infection control to prevent disease transmission; standard precautions should be applied for all patient care. Any patient suspected to have monkeypox should be directed to his or her primary care provider, health department clinic, or urgent care center for evaluation. Similar to other contagious lesions, dental care should be avoided until all lesions have crusted, those crusts have separated, and a fresh layer of healthy skin has formed underneath (Table 2).16

Since COVID-19, oral health professionals are profoundly adept with infection control measures and use of PPE. The CDC’s “Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings—2003” provides comprehensive recommendations for preventing and controlling infectious diseases and managing personnel health and safety related to infection control.17 Aerosol-producing procedures or equipment may resuspend dried material from lesions and should be avoided.16 Clinicians should wear gowns, gloves, eye protection, and K95 or N95 facemasks.

As an emerging viral pathogen, high-level disinfectants are indicated for use. Monkeypox virus is in the Tier 1 emerging viral pathogen category: an enveloped virus that is easiest to inactivate. Disinfectants damage their lipid envelope, resulting in the virus being no longer infectious.18 Clinicians can visit the US Environmental Protection Agency’s website to determine which disinfectant is effective in destroying the emerging virus and follow manufacturer directions for use.19

Clinicians can use the CDC’s DentalCheck mobile application, developed directly from the Infection Prevention Checklist for Dental Settings Basic Expectations for Safe Care, to create checklists to periodically assess practices in their facility to ensure they are meeting the minimum requirements for safe care. The infection control coordinator or compliance officer can use this annually or semi-annually to assess administrative policies and procedure.18

![]() Resources For Clinicians

Resources For Clinicians

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends that individuals whose jobs may expose them to Orthopoxviruses, such as monkeypox, should receive either the ACAM2000 or JYNNEOS vaccine. This is known as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Clinical laboratory personnel who perform testing to diagnose Orthopoxviruses; research laboratory workers who directly handle cultures or animals contaminated or infected with Orthopoxviruses; certain healthcare and public health response team members designated by public health authorities; and healthcare personnel who administer ACAM2000 or anticipate caring for many patients with monkeypox should get PrEP.14 At this time, most clinicians and laboratorians in the US performing the Orthopoxvirus generic test to diagnose Orthopoxviruses, including monkeypox, are not advised to receive Orthopoxvirus PrEP.

The CDC in conjunction with the ACIP provides recommendations on who should receive smallpox vaccination in a nonemergency setting. Currently, vaccination with ACAM2000 is recommended for laboratorians working with certain Orthopoxviruses and military personnel. On November 3, 2021, the ACIP voted to recommend JYNNEOS PrEP as an alternative to ACAM2000 for individuals at risk for exposure to Orthopoxviruses.14

Summary

All healthcare personnel need to remain informed about monkeypox virus, current status and updates, and preventive measures to avoid transmission. Oral health professionals should be knowledgeable about infectious diseases and provide guidance to their patients. By maintaining the highest standard of infection control and care, in accordance with CDC guidelines, dental personnel can continue to effectively contribute to disease prevention. More information about monkeypox can be found at: cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/about.html and cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/index.html.

References

- Weinstein RA, Nalca A, Rimoin AW, Bavari S, Whitehouse CA. Reemergence of monkeypox: prevalence, diagnostics, and countermeasures. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1765–1771.

- Sklenovská N, Van Ranst M. Emergence of monkeypox as the most important orthopoxvirus infection in humans. Front Public Health. 2018;6:241.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Monkeypox. Available at: cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/about.html. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monkeypox: Frequently Asked Questions. Available at: cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/faq.html. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monkeypox: Past U.S. Cases and Outbreaks. Available at: cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/outbreak/us-outbreaks.html. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Monkeypox Outbreak 2022: Situation Summary. Available at: cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/떖/index.html. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- World Health Organization. Monkeypox. Available at: who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/monkeypox. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monkeypox: How it Spreads. Available at: cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/transmission.html. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monkeypox: Clinical Recognition. Available at: cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/clinical-recognition.html. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monkeypox: Prevention. Available at: cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/prevention.html. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monkeypox and Smallpox Vaccine Guidance. Available at: cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/smallpox-vaccine.html. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social Gatherings, Safer Sex, and Monkeypox. Available at: cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/specific-settings/social-gatherings.html. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- Worl Health Organizations. Monkeypox: Questions and Answers. Available at: who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/monkeypox. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidance for Tecovirimat Use Under Expanded Access Investigational New Drug Protocol during 2022 U.S. Monkeypox Cases. Available at: cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/Tecovirimat.html. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- AP News. German Panel Recommends Vaccines After Exposure to Monkeypox. Available at: apnews.com/article/health-germany-smallpoxaf95c70ee85d1463ef23b21f18d2 477c. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- New York City Department of Health. Monkeypox (Orthopoxvirus). Available at: www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/health/health-topics/monkeypox.page. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- Kohn WG, Collins AS, Cleveland JL, et al. Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings—2003. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(RR-17):1-61.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infection Prevention Checklist for Dental Settings Basic Expectations for Safe Care. Available at: cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/pdf/safe-care-checklist-a.pdf. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Disinfectants for Emerging Viral Pathogens: List Q. Available at: epa.gov/pesticide-registration/disinfectants-emerging-viral-pathogens-evps-list-q#search. Accessed September 26, 2022.

FIGURES 1-2. KATERYNA KON/SHUTTERSTOCK.COM

FIGURE 3. ALESSANDRO MANCUSO C/SHUTTERSTOCK.COM; FIGURE 4. BERKAY ATASEVEN/SHUTTERSTOCK.COM

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. October 2022; 20(10)28, 31-33.