PLYUSHKIN / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

PLYUSHKIN / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Maintain Visual Acuity

Strategies to reduce vision-related risks and improve ocular health.

Eye performance is intimately related to balance, perception, ability to perform activities of daily living, and quality of life. It directly impacts how oral health professionals engage with their patients and provide treatment. Specifically, eye performance is essential to the ability to provide effective, efficient, and quality patient care.

The importance of occupational eye health is emphasized in the Healthy People 2020 Vision Objectives, which are designed to decrease occupational eye injuries and reduce visual impairment.1 Although dental hygienists and dentists rely heavily on their visual acuity when working, some literature suggests that, when it comes to eye health, prevention strategies are not being routinely implemented.2–4 As dental hygienists focus on preventive treatment and rely on visual acuity, they should strive to prevent ocular risks and hazards and employ strategies to maintain and improve their ocular health.

Ocular Risk Factors

Eye health is multifactorial and risk factors are shared between eye health and overall health. As such, oral health professionals should examine their health history to ascertain their risk level for eye diseases. Health problems that may increase the risk for some eye diseases include:5–7

- Hypertension

- Diabetes mellitus

- Measles

- Lyme disease

- Shingles

- Sjögren syndrome

- Rosacea

- Liver disease

- Vitamin deficiencies

- Graves’ disease

- Sickle cell disease

Additionally, examining family history of eye diseases and systemic conditions is critical as there are more than 350 hereditary eye diseases.8

While well-controlled health problems will, most likely, have little effect on eye disease risk, factors such as sedentary lifestyle, poor nutrition, and smoking/vaping tobacco and marijuana may significantly increase the risk for eye diseases.5

Age is another risk factor for eye diseases. As people age, the cellular integrity, lens function, and pupil performance all diminish.9 These biological eye changes can affect visual acuity including areas of peripheral vision, close-up vision, and color detection; all of which are vital to dental hygienists during clinical care.9,10

Ocular Occupational Hazards

In addition to health conditions and controllable and uncontrollable risk factors, dental hygienists are exposed to numerous ocular risks due to the nature of clinical practice. The frequent and repetitive procedures performed by dental hygienists put them at high risk for ocular damage.4,11 Additionally, potential exposure to chemicals, aerosols, bloodborne pathogens, foreign materials, other potentially infectious materials (eg, saliva or biofilm), dental materials (eg, etch or sealant materials), blue light, and lasers are daily occupational hazards.9,12 Exposure to occupational hazards may cause eye injuries if proper precautions are not followed during every procedure, regardless of the perceived risk level.12

A 2017 literature review found two main categories of eye damage in dentistry: infection-related and trauma-related.12 The potential effects of infection-related injury included bacterial and viral conjunctivitis, bacterial and viral keratitis, human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. The impact of trauma-related injuries included corneal abrasion, hemorrhage, torn iris, lacerations, and chemical injuries.12,13 One study also found dental personnel reported a 42.3% rate of foreign-body ocular injury.14 Injuries occurred most commonly while using handpieces and ultrasonic devices. On the other hand, another study concluded that most eye injuries among oral health professionals were not severe and most symptoms were mild.15

Other trauma-related injuries are caused by lasers or blue light from curing devices. These injuries are usually painless and may go untreated. Exposure to low- and medium-intensity lasers can injure the eye due to the centered effects on the cornea and lens of the eye.16 Blue light devices used for curing resin materials may emit 430 nanometers (nm) to 480 nm of possible retina-damaging radiation. Damage to the retina can occur in the 435 nm to 440 nm range.17 Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) used in most headlamps and operatory lights may also contribute to injuries when used for extended periods (> 20 minutes of constant use and > 5 hours accumulative time).17

Strategies for Ocular Health

Dental hygienists can minimize ocular risks by incorporating specific strategies into their daily practices. Safe practices start with identifying and controlling any underlying health-related risk factors. Eye health is also affected by overall health; therefore, dental hygienists may consider adding dark leafy greens and foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids to their diet to support eye health. Smoking and/or vaping tobacco or marijuana can damage the optic nerve and contribute to macular degeneration and cataracts (Figure 1).5 Prioritizing an annual eye exam is crucial in identifying eye changes early before they interfere with functionality.

Safe infection control practices include proper and frequent hand hygiene, avoiding touching the eyes, minimizing aerosol and foreign material spatter, and donning properly fitting safety glasses. Dental hygienists should refer to guidance from the Organization for Safety Asepsis and Prevention and United States Centers for Disease Control when selecting infection control protocols and appropriate protective eyewear.18,19

The use of loupes with effective side-shields complies with eye protection guidelines and may benefit eye health. One considerable benefit is increased visual acuity, which enhances precision and performance. In a recent study investigating dental hygienists’ visual acuity while wearing loupes, some dental hygiene participants could distinguish designs that were 300% smaller than other participants.20 Furthermore, magnification use overcame natural near vision restrictions in participants ≥ 40 years of age. With magnification, their visual ability was equal to the visual performance of younger participants who did not use magnification. The authors of the study strongly encourage the early adoption of magnification among those with any visual insufficiencies and those age 40 and older.21 Research indicates loupes may improve ergonomics, provide optimal light (with headlamps), and reduce eye fatigue.9,21,22

Headlamps and overhead lights may also help protect eye health. In order to ensure the safe use of headlamps and overhead lights, optimal but minimum brightness should be implemented, glare should be reduced, and the duration of time used should be limited.17,23 Similarly, laser-specific eye protection and orange protection filters or glasses should be implemented when using light-emitting curing or laser devices in addition to avoiding direct exposure to the light-emitter.12,16,17,23

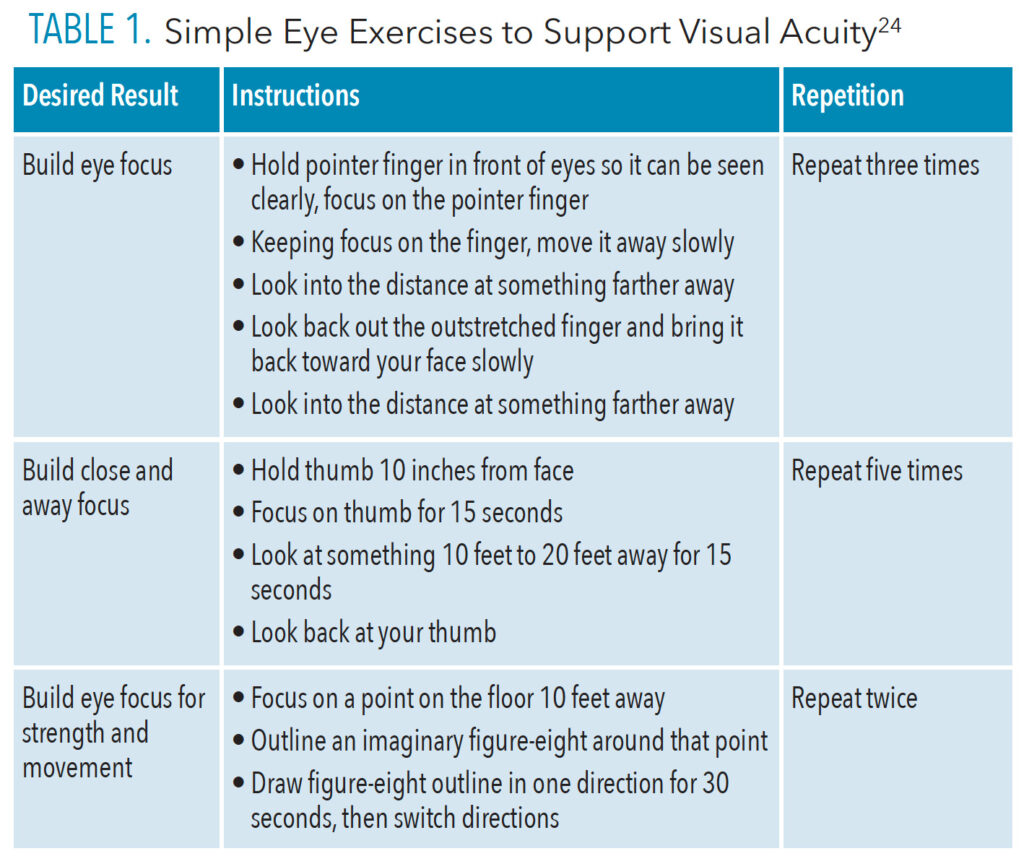

Eye exercises may also be helpful. A simple yet effective exercise is the “20-20-20 rule.”24 The rule is to look at something 20 feet away for 20 seconds every 20 minutes.24 Table 1 provides additional eye exercises designed to prevent eye strain, however, they will not improve eye sight.

Conclusion

Ocular health recommendations and practices focus on risk identification and mitigation, including prevention and maintenance strategies. Ocular risks and hazards raise dental hygienists’ risk for occupational injury. Dental hygienists depend on optimal eye health and should prioritize ocular health to increase career longevity.

References

- Healthy People 2020. Vision. Available at: wayback.archive-it.o/g/쐾/㬾/https://www.healthypeople.gov/떔/topics-objectives/topic/vision/objectives. Accessed September 21, 2022.

- Chadwick RG. Factors influencing dental students to attend for eye examinationJ J Oral Rehabil.1999;26:72–74.

- Chadwick RG, Alatsaris M, Ranka M. Eye care habits of dentists registered in the United Kingdom. Br Dent J. 2007;203:E7.

- Azodo CC, Ezeja EB. Ocular health practices by dental surgeons in Southern Nigeria. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:115.

- National Eye Institute. Keep Your Eyes Healthy. Available at: nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/healthy-vision/keep-your-eyes-healthy. Accessed September 21, 2022.

- National Eye Institute. Eye Conditions and Diseases. Available at: nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases. Accessed September 21, 2022.

- Sjögren’s Foundation. Understanding Sjögren’s symptoms. Available at: sjogrens.org/understanding-sjogrens/symptoms. Accessed September 21, 2022.

- Research to Prevent Blindness. Hereditary Ocular Disease. Available at: rpbusa.org/rpb/resources-and-advocacy/resources/rpb-vision-resources/hereditary-ocular-disease. Accessed September 21, 2022.

- Lintag-Nguyen K, Dahm TS. Ensure career longevity with eye health. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2021;19(10):14–18.

- Heiting G. How vision changes as you age. Available at: allaboutvision.com/over60/vision-changes.htm. Accessed September 21, 2022.

- Ajayi YO, Ajayi EO. Prevalence of ocular injury and the use of protective eye wear among the dental personnel in a teaching hospital. Nig Q J Hosp Med. 2008;18:83–86.

- Ekmekcioglu M, Unur M. Eye-related trauma and infection in dentistry. Istanbul Univ Rac Dent. 2017;51:55–63.

- Al Wazzan KA, Almas K, Al Qahtani MQ, Al Shethri SE, Khan N. Prevalence of ocular injuries, conjunctivitis and use of eye protection among dental personnel in Riyardh, Saudi Arabia. Int Dent J. 2001;51:89–94.

- Farrier SL, Farrier JN, Gilmour AS. Eye safety in operative dentistry: a study in general dental practice. Br Dent J. 2006;200:218–223.

- McDonald RI, Walsh LJ, Savage NW. Analysis of workplace injuries in a dental school environment. Aust Dent J. 1997;42:109–113.

- Barkana Y, Belkin M. Laser eye injuries. Surv Ophthalmol. 2000;44:459–478.

- Price RBT, Labrie D, Bruzell EM, Sliney DH, Strassler HE. The dental curing light: a potential health risk. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2016;13:639–646.

- Arsenault P. Eye safety in dentistry updates: “the new standard in eye safety practice.” J Dent Infect Control Safety. 2021;3.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary of Infection Prevention Practices in Dental Settings: Standard Precautions. Available at: cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/summary-infection-prevention-practices/standard-precautions.html. Accessed September 21, 2022.

- Eichenberger M, Perrin P, Sieber KR, Lussi A. Near visual acuity of dental hygienists with and without magnification. Int J Dent Hyg. 2018;16:357–361.

- Aldosari MA. Dental magnification loupes: an update of the evidence. J Contemp Dent Pract. 20212;22:310–315.

- Arnett MD, Eagle I. Impact of loupes and lights on visual acuity and ergonomics. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2021;19(8):21–23.

- Mathew J, Nair M, Nair NA, James B, Syriac G. Ocular hazards from use of light-emitting diodes in dental operatory. J Indian Acad Dent Spec Res. 2017;4:28–31.

- Healthline. Eye exercises: how-to, efficacy, eye health and more. Available at: healthline.com/health/eye-health/eye-exercises. Accessed September 21, 2022.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. October 2022; 20(10)18,21-22.