The Oral Implications of MS

Effectively providing dental care to patients who have multiple sclerosis.

This course was published in the January 2010 issue and expires January 2013. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Describe how multiple sclerosis (MS) affects the nervous system.

- Recognize systemic and oral manifestations of MS.

- Identify and manage oral side effects of common MS medications.

A progressive, neurological, and degenerative disorder, multiple sclerosis (MS) affects approximately 400,000 people in the United States. More women than men are diagnosed with MS and the age of diagnosis is usually between 20 years and 40 years of age.1-4 Although the exact etiology of MS is unknown, it is generally considered an autoimmune disorder that can be influenced by environment, genetics, climate, and geography.1-2,4

MS affects the central nervous system by damaging the myelin sheathing that surrounds the nerves. The damaged areas are called plaques, which negatively affect sensory and motor nerve transmissions.1,4

There are four types of MS: benign, relapsing/remitting, secondary progressive, and primary progressive. Benign MS affects approximately 20% of individuals diagnosed with MS4 and manifests with mild initial symptoms that disappear. Benign MS is only diagnosed 10 years to 15 years after the initial onset of the disease and patients do not experience permanent disability.1,4 Relapsing/remitting MS accounts for 25% of cases and is characterized by new or previous symptoms spontaneously recurring and then relapsing for varied amounts of time. Patients with this type of MS are usually symptom free during early remissions, however, as time passes and the demyelination progresses, their condition worsens.1 Secondary progressive MS affects approximately 40% of MS patients and begins as the relapsing/remitting type. Over time the remission periods stop and the MS becomes progressive, which usually takes 15 years to 20 years.1 Primary progressive MS is the most severe form of MS and accounts for 15% of cases. Remission does not occur and symptoms steadily worsen, increasing the patient’s disability.1 Primary progressive MS can be very aggressive and is physically devastating to patients.

SYMPTOMS OF MS

MS causes a variety of symptoms that vary depending on the severity of the disease and the nerves that are affected. MS can initially present as numbness or weakness of the limbs (usually unilaterally or limited to the lower half of the body), tingling or pain in certain parts of the body, blurring of vision, double vision or partial loss of vision and/or optic neuritis (an inflammation of the optic nerve associated with MS and autoimmune disorders), tremors, fatigue, dizziness, and trigeminal neuralgia (painful swelling of the trigeminal nerve, which delivers feeling to the face and surface of the eye).1-2,4

Besides trigeminal neuralgia, oral manifestations commonly include paresthesia and facial palsy.5 Facial palsy caused by MS usually lacks the pain behind the ear and the loss of taste that are associated with Bell’s palsy.6 Dental professionals should take note of patients who present with trigeminal neuralgia if they have a past history of neurological problems, the pain lasts for extended periods of time (minutes or hours), or the pain is bilateral.6 Trigeminal neuralgia can be triggered by routine actions such as toothbrushing, chewing, or touching. Patients may be disinclined to continue good self-care practices if they trigger painful attacks.6 Medical management of the patients’ systemic conditions may be necessary before they are able to achieve good dental health and oral hygiene practices, thus, a referral to a physician for a consultation or follow-up is indicated.

Muscle spasticity is an uncontrolled increase in muscle activity that can result in loss of coordination, weakness, decrease or loss of mobility, stiffness, loss of range of motion in joints, pain, loss of sleep, reduced quality of life, and social isolation.7 Spasticity is caused by the brain or spinal cord lesions that result from myelin destruction. When spasticity is related to MS, it is more difficult to control because, in most cases, the disease progressively worsens. Treatment of spasticity depends on the intensity, frequency, and impact on lifestyle.7

Table 1 includes the common medications used to treat spasticity, as well as other classes of drugs used for MS management. Drug therapy is intended to manage the symptoms and improve the patient’s quality of life with the goals of preventing relapse, reducing the disease’s severity and intensity, and slowing the progression of MS.5

CASE REPORT

A 54-year-old Caucasian man presented for a routine dental hygiene prophylaxis. His medical history was unremarkable until the age of 19 when he began experiencing the common symptoms of MS: weakness, ataxia (lack of coordination of muscle movements), heat sensitivity, and optic neuritis (inflammation of the optic nerve causing sudden, reduced vision in the affected eye).4,10 The patient was diagnosed with MS through a lumbar puncture and confirmed by an MRI.

A 54-year-old Caucasian man presented for a routine dental hygiene prophylaxis. His medical history was unremarkable until the age of 19 when he began experiencing the common symptoms of MS: weakness, ataxia (lack of coordination of muscle movements), heat sensitivity, and optic neuritis (inflammation of the optic nerve causing sudden, reduced vision in the affected eye).4,10 The patient was diagnosed with MS through a lumbar puncture and confirmed by an MRI.

The patient was treated with drugs for 12 years, during which time he was able to continue working part-time. After 17 years, the patient’s symptoms progressed to the point where he required a walker and then the use of a motorized scooter. From 1998 to 2007 the patient was treated with biweekly betainterferon injections. In late 2007 the patient had a baclofen pump placed.

The patient has received regular medical and dental treatment and is managed by a neurologist who specializes in MS research. His medications are adjusted as needed and bone scans are performed every 3 years to monitor bone density. At the time of dental treatment the patient was on several prescription medications for hypercholemia, hypertension, hypothyroidism, sleep apnea, and depression. Dental considerations for these drugs include xerostomia and spasticity, which can lead to opportunistic infections such as candidiasis or those caused by bruxism. He was also taking the following medications to address his MS symptoms: alendronate to prevent bone loss, baclofen, tizanidine, hyoscyamine for spasticity, and weekly doses of steroids to decrease inflammation. The patient was receiving 40 mg of dexamethasone per week and had recently discontinued 1 g per week of intravenous methylprednisolone in order to decrease the inflammation from the plaques and lesions in his brain. Due to the large dose of the steroids, a medical clearance request form was sent to the patient’s neurologist prior to dental treatment; the patient was unconditionally cleared for treatment.

The patient’s social history included a bachelor’s degree and a career in retail pharmacy. The patient was widowed with no children. Since 2007 the patient has lived in a senior retirement community because he can no longer care for himself. He uses a motorized scooter in order to maintain mobility and independence.

CLINICAL FINDINGS

The 2-hour appointment was scheduled to include intraoral photography; dental, periodontal, and plaque charting; treatment planning; patient education; and scaling as necessary. Prior to the appointment, a list of medications and brief medical history was requested by the clinician, followed by a 45- minute phone interview in order to maximize the appointment time.

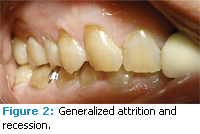

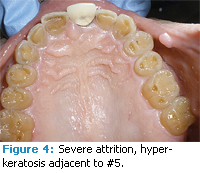

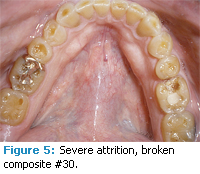

The patient presented with generally healthy periodontal tissues. There was a slight to moderate reduction in salivary flow, evidenced by the mirror sticking to the patient’s cheek and the patient reporting frequent dry mouth. There was slight bleeding on probing with a total of 10 bleeding points or 6%. The majority of bleeding points were found on the left side of the mouth. Probing depths ranged from 1 mm to 3 mm throughout the mouth. He had bilateral maxillary recession of 1 mm to 2 mm on the buccal surfaces of the posterior teeth with generalized abrasion. Severe generalized attrition was present on both arches (Figures 1-5). There were two sites of hyperkeratinized tissue on the labial and buccal mucosa adjacent to #2 and #5 (Figure 4). Clinical impression was frictional keratosis from bruxism, which may be a result of muscle spasticity. There were few prior restorations. However, the class II composite on #30 was broken and partially missing (Figure 5).

TREATMENT

Modifications to the operatory were unnecessary with the exception of selecting a dental unit with space for patient transfer from a motorized scooter. The patient was able to use his arms to move his upper body and the clinician lifted the patient’s legs from the scooter into the dental chair. A steep semisupine position was used for maximum patient comfort with the clinician working from a standing position.

The patient’s health-related knowledge was very high and he was meticulous about maintaining his health. The patient’s dental knowledge was moderate and dental health was a priority. He received regular dental care, brushed twice daily with a sonic toothbrush, and flossed at least once per day without the use of a flossing aid. Despite his good self-care practices, the patient had a plaque score of 57%, with the majority of the plaque found interproximally.

The dental hygiene care plan was tailored to address education about the patient’s abrasion, recession, and need for improved interproximal plaque removal. The clinician demonstrated the correct use of the power toothbrush to help curb further abrasion. The patient was also shown how to correctly angle the bristles at a 45° angle to the gingiva for greater marginal plaque removal. Flossing technique was also addressed; the patient was shown how to use a c-shape technique around the mesial and distal surfaces of each tooth. Due to the patient’s knowledge and pre-existing good hygiene practices, simple adjustments to brushing and flossing technique for better interproximal plaque removal and minimizing further tissue damage were easily understood and implemented by the patient. The clinician and patient also discussed his current manual dexterity and possible future oral hygiene needs. The patient stated that he was able to brush and floss without difficulty at this time. He was made aware of other oral hygiene options, such a dental water jet and floss holders, if his dexterity deteriorated.

Xerostomia as a result of medications was also discussed by the patient and clinician. The patient reported frequent dry mouth, which he dealt with by drinking water. The patient was made aware of overthe- counter salivary substitutes and dry mouth relief products.

Xerostomia as a result of medications was also discussed by the patient and clinician. The patient reported frequent dry mouth, which he dealt with by drinking water. The patient was made aware of overthe- counter salivary substitutes and dry mouth relief products.

The severe attrition of occlusal and incisal surfaces was also discussed. The patient was shown areas of attrition and the clinician explained the process of attrition. Additional evidence of bruxism included the hyperkeratinized patches of tissue across from #2 and #5. The patient may have been experiencing attrition as a result of clenching and grinding due to the muscle spasticity of MS. The patient had not been aware that the attrition was abnormal and that prevention options, such as an occlusal guard, were available. The patient presented to his private practice dentist for the broken composite on #30 and for continued regular preventive dental care.

The attrition, recession, and hyperkeratinized tissue were areas of concern that warrant monitoring and regular professional care. Along with xerostomia, these findings were the most significant oral complications related to MS for this patient. If this patient was less motivated to be healthy, poor oral care practices and habits could easily put him at risk for caries and periodontal diseases. His career in pharmacy was a great asset in his understanding and management of MS. He was knowledgeable about his physical and oral health and motivated to be as healthy as possible. The compliance and enthusiasm of the patient allowed education to be very individualized and effective. He was realistic about his condition and willing to share his experiences with MS in order to help educate others.

CONCLUSION

MS patients are all unique individuals with a wide variety of abilities and needs. Good oral health is extremely important, however, achieving this goal may present unique challenges. Modifications to dental care and selfcare strategies are vital to success. Depending on the oral manifestations of MS and the related medications, the clinician will have to create a treatment plan, educate, and make oral hygiene care recommendations accordingly. The mobility, dexterity, and spasticity of the patient will need to be considered when scheduling office visits and deciding on oral care routines with the patient.Marlaina J. Reich, RDH, BAS, is an assistant clinical professor at Baylor College of Dentistry in Dallas. She is currently working on her master’s degree in Dental Hygiene Education.

REFERENCES

- Fiske J, Griffiths J, Thompson S. Multiple sclerosis and oral care. Dent Update. 2002;29:273-283.

- Multiple sclerosis. Mayo Clinic. Available at: www.mayoclinic.com/health/multiplesclerosis/DS00188. Accessed December 2, 2009.

- Symons AL, Borolanza M, Godden S, Seymour G. A preliminary study into the dental health status of multiple sclerosis patients. Spec Care Dentist. 1993;13:96-101.

- Fischer DJ, Epstein JB, Klasser G. Multiple sclerosis: an update for oral health care providers. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009:108:318-327.

- Chemaly D, Lefrançois A, Pérusse R. Oral and maxilofacial manifestations of multiple sclerosis. J Can Dent Assoc. 2000;66:600-605.

- Scully Cbe C, Shotts R. The mouth in neurological disorders. Practitioner. 2001;254:539,542- 546,548-549.

- Haselkorn JK, Loomis S. Multiple sclerosis and spasticity. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2005;16:467-481.

- Mosby’s Dental Drug Reference. 8th ed. St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2008.

- Optic neuritis. Mayo Clinic. Available at: www.mayoclinic.com/health/optic-neuritis/DS00882. Accessed December 2, 2009.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2010; 8(1): 52-55.