CYANO66 / ISTOCK / THINKSTOCK

CYANO66 / ISTOCK / THINKSTOCK

The Impact of Diet and Nutrition On Oral Health

Dental hygienists can help patients improve their oral health by identifying dietary contributors to oral disease, assessing patients for nutrition-related risks, and providing dietary counseling.

This course was published in the April 2016 issue and expires April 20, 2019. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define the impact of diet on oral health.

- Discuss how to perform nutritional assessment and provide dietary counseling in the dental setting.

- Identify strategies to help patients understand how dietary changes may improve their oral health.

Dental hygienists serve as health care educators in the dental setting. Oral hygiene instruction includes diet and nutrition counseling for the prevention and/or treatment of oral diseases. Diet—defined as the combination of foods consumed—may impact caries risk, soft tissue health, and responses to injury and infection. Nutrients contained within foods are essential for growth, maintaining tissue health, repairing injured tissue, and providing energy for daily activities. Oral health professionals need to be prepared to identify dietary contributors to disease, assess patients for nutrition-related risks, and provide dietary counseling to mitigate these risks.

NUTRITION AND DENTAL CARIES

Dental caries is a disease in which the acid produced by oral bacteria dissolves enamel or dentin in a specific location. Acid is produced by bacterial fermentation of dietary carbohydrates. Oral bacteria cannot ferment proteins, fats, or non-nutritive sweeteners such as aspartame and sucralose.1 As such, carbohydrates are considered cariogenic, while proteins, fats, and non-nutritive sweeteners are noted as noncariogenic. Dietary carbohydrates at risk for fermentation include sugars, starches, and hydrolyzed starch products.2,3 Common dietary sugars are glucose, fructose, sucrose, and lactose. Sugars are commonly added to sweeten beverages, candies, baked goods, and other foods. Starches are long saccharide chains that are made from sugars. They are found in grains, vegetables, and baked goods. Intermediary carbohydrates produced by the hydrolysis of starches are also fermentable by oral bacteria. Hydrolysis—the splitting of large carbohydrates into small carbohydrates through the addition of water—slowly severs the bonds of starch molecules. This results in fewer saccharide units per molecule. Hydrolyzed sugars are called modified starches, oligosaccharides, and maltodexrins on food labels.

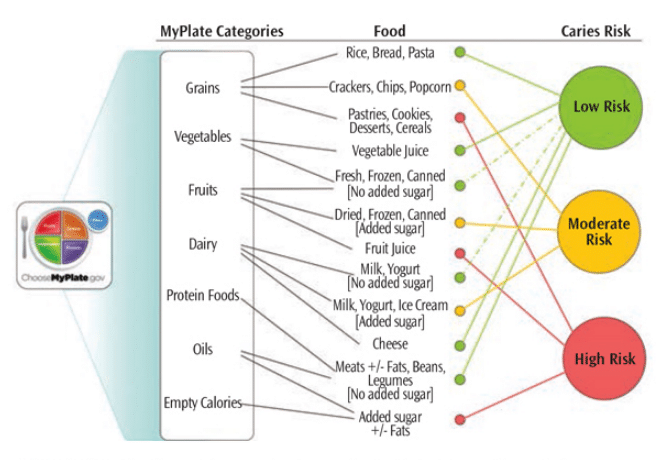

The caries risk associated with foods depends on their carbohydrate composition and manner of consumption (Figure 1). Typically, unsweetened grains, vegetables, fruits, and dairy products present low caries risk. However, foods containing added sugars and/or hydrolyzed starch products are associated with increased caries risk.3 While potato chips, crackers, and cereals may not contain sugars, they do have oligosaccharides (saccharide polymers composed of three to 10 simple sugars) and maltodextrins (polysaccharides used as food additives) that can, in time, can be easily fermented by bacteria in the mouth. Beverages made with natural sugars or added sugars are associated with higher caries risk than solid foods containing sugars.4–6

Consumption behaviors can also modify caries risk.5,7 Behaviors that limit exposure to cariogenic foods/beverages decrease caries risk, while behaviors that increase exposure raise caries risk. Structured meals and snacks with no more than five to six eating events per day tend to decrease risk, while unstructured eating events, grazing, and sipping sugar-sweetened beverages increase caries risk. Oral habits such as swishing beverages, holding foods and beverages in the mouth, and pocketing foods in the cheek are associated with increased caries risk.

A significant reduction or elimination of foods containing added sugars is a prudent dietary goal. When added sugar is consumed, behaviors that limit oral exposure time—such as brief structured eating intervals, prompt swallowing of chewed foods, and the use of straws—tend to decrease caries risk. In addition, rinsing with water, chewing sugar-free gum, and appropriate oral hygiene practices also reduce caries risk.

ACIDS AND EROSION

Erosion of enamel and/or dentin occurs when acids dissolve the tooth structure. The source of acids can be either exogenous (dietary) or endogenous (gastrointestinal). Soft drinks, 100% fruit juices, juice drinks, wine, herbal teas, and sports drinks are all highly acidic.8,9 Foods associated with increased erosion risk include fruits, particularly citrus; sour candies; and foods prepared with vinegar, wine, or acidic spices.8,10 To prevent diet-related erosion, exposure to acidic foods or beverages must be limited. Avoiding the swishing of beverages and pocketing of foods in the mouth is also important. Patients should be advised to wait to brush their teeth until at least 20 minutes following consumption of an acidic food/beverage to enable saliva to neutralize the oral cavity.

DIET AND PERIODONTITIS

Tissue inflammation and loss of the supporting bone and soft tissue structures characterize periodontitis. Although periodontitis is a bacterial plaque-related disease, nutrition can influence susceptibilities to the disease. Conversely, prevention and treatment of periodontal diseases depend on a normal functioning immune system, which, in turn, depends on appropriate nutrition. Nutrition-related diseases, including obesity and poorly controlled diabetes, increase risks for periodontal diseases.

Adequate energy (calories) and protein are necessary for the performance of daily activities and metabolic functions. Without adequate energy or protein, individuals become lethargic, growth slows, wound healing is impaired, and susceptibility to infections increases. Many nutrients have essential functions that support the immune system.11,12 While the consequences of extreme nutrient deficiencies are well known, the implications of subtle nutrient deficiencies in relation to periodontal diseases are less clear. In general, periodontal diseases are more common and severe in individuals with protein-energy malnutrition than in those without.11 Vitamin C deficiency has been associated with increased bleeding on probing, while high serum vitamin C levels have been linked to reduced risk of periodontitis in both smokers and nonsmokers.12 Similarly, low calcium and vitamin D intake may be related to periodontitis.11,12

Obesity and poorly controlled diabetes are thought to support a pro-inflammatory state and increase susceptibilities to infections like periodontitis. The size of fat cells correlates with the inflammatory markers tumor necrosis factor-? and interleukin-6 in young children.13 Excess weight and waist circumference are associated with increased risks for periodontitis in late adolescence.14 A high body mass index increases the risk of periodontitis in adults.15 The relationship between chronic periodontitis and poorly controlled diabetes is well established.11,16

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Dietary Guidelines provide general recommendations for healthy diets to reduce the rates and intensity of chronic diseases.17,18 The USDA’s ChooseMyPlate.gov provides dietary recommendations based on age, gender, and activity level.19 In general, deficient nutrient intakes should be corrected through dietary changes. Nutritional supplements, however, may be appropriate for addressing deficiencies for short intervals. For example, individuals who smoke often have low serum vitamin C levels and might benefit from vitamin C supplementation. In addition to selecting foods to meet nutrient requirements, dietary recommendations for weight management and glycemic control in patients with obesity and/or diabetes are designed to reduce inflammatory responses and the risk for the periodontal diseases.

NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT

Nutritional assessment is the first step in addressing diet with patients. Subsequent stages comprise planning and implementing interventions and evaluating their effectiveness. The depth of this process depends on the goals of the assessment, which can range from helping patients make better food choices to identifying those experiencing malnutrition. Malnutrition results from deficient intake of energy or nutrients, excessive intake of energy or nutrients, or an imbalance of nutrient consumption.20,21 Signs and symptoms of malnutrition can be overt or subclinical. Secondary causes of malnutrition are not necessarily associated with dietary intake but, rather, are problems with the absorption, utilization, or excretion of nutrients.

A nutritional assessment includes questions regarding the frequency of exposure to fermentable carbohydrates, history of sweetened beverage consumption, level of compliance with ChooseMyPlate, and history of weight loss or gain of more than 10 lbs during the preceding 6 months. Patients identified as high risk for malnutrition during the initial screening or those who have diet-related diseases should receive a more detailed nutritional assessment that includes an examination of medical, social, and medication histories; anthropometrics; physical examination; and diet assessment. The information gathered during the assessment process provides the foundation for identifying appropriate interventions.

Historical information is typically obtained during patient interviews or from medical records, and it identifies patient characteristics that influence food intake and/or nutrient requirements. Assessment of medical histories is designed to identify illnesses, treatments, or conditions that increase the risk of malnutrition. The assessment of socioeconomic history helps to detect financial and environmental factors that limit patients’ abilities to buy or prepare appropriate foods. By evaluating patients’ medication usage, clinicians can consider whether supplements, over-the-counter medications, prescription medications, and/or recreational drugs may cause nutrient-medication interactions.

Anthropometrics refer to measures of body size and proportion, which provide an indirect assessment of body composition. Weight and height are the most common measurements taken, but waist and hip circumference measurements are becoming more common. Waist circumference or the waist-to-hip ratio can identify the presence of abdominal obesity, which is strongly associated with metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.21 The relationship between weight and height (body mass index) may help to identify nutrition-related disorders.21

Physical examinations are visual evaluations of the color, shape, texture, and symmetry of tissues.20,21 Inspection of body size and shape will reveal the presence of excesses fat tissue and/or loss of muscle or fat tissue. Dry skin, brittle hair, pale eyes, and mottled nails are consistent with visible nutrient deficiencies. Changes to oral tissues including magenta tongue, cracked lips, or bleeding gums also suggest nutrient deficiencies.

In the assessment of dietary behaviors, current and past food consumption is recorded and compared to the nutritional guidelines provided by ChooseMyPlate to identify inadequate or excessive food intakes.19 The assessment of past food consumption helps clinicians detect nutrition issues that may have contributed to disease but have since been corrected. For example, a patient recognized that his or her high intake of sugar-sweetened beverages was causing recurrent caries and, thus, eliminated these beverages from his or her diet. Dietary habits such as meal patterns, location of consumption, and frequency of intake are assessed to identify factors that influence the length of carbohydrate exposures. Dietary preferences, family and/or cultural dietary restrictions, and feeding skills are also evaluated before recommendations are made.

Current dietary intake can be assessed by asking patients to recall what they have eaten over the past 24 hours or what they typically eat in a day or through the use of food records and food frequencies. Food records require patients to record their food consumption for 3 days to 7 days. While food records do not rely on memory, accuracy can be hindered by the tendency to overstate the consumption of healthy foods or omission of foods that are viewed as “bad.” Food frequencies refer to the frequency and volumes of food/beverages consumed and are based on patient memory. Most dietary assessment tools include questions about behaviors associated with food intake.

DIETARY COUNSELING

Dietary counseling includes the identification of dietary interventions to improve food choices and dietary behaviors.22 Information gathered during the nutrition assessment is used to determine what dietary factors may be contributing to current disease or raising the risk of future disease. Following identification of the risk factors, the diet and dietary behaviors are evaluated to identify strategies to modify food intakes and/or dietary behaviors to improve nutritional health.

Once strategies for modifying the diet are identified, patient counseling begins. Patients should be informed of their current oral health status, their risk for oral diseases, and how their food choices and dietary behaviors influence these. Clinicians should also evaluate patients’ general dietary knowledge so that appropriate education can be provided. Patients need to understand the relationship between their oral health concerns and their diet in order to make informed decisions regarding behavior change. After sharing the health status and dietary information, clinicians should identify patients’ perceptions of any suspected dietary problems and how these may influence their willingness to modify their diets.

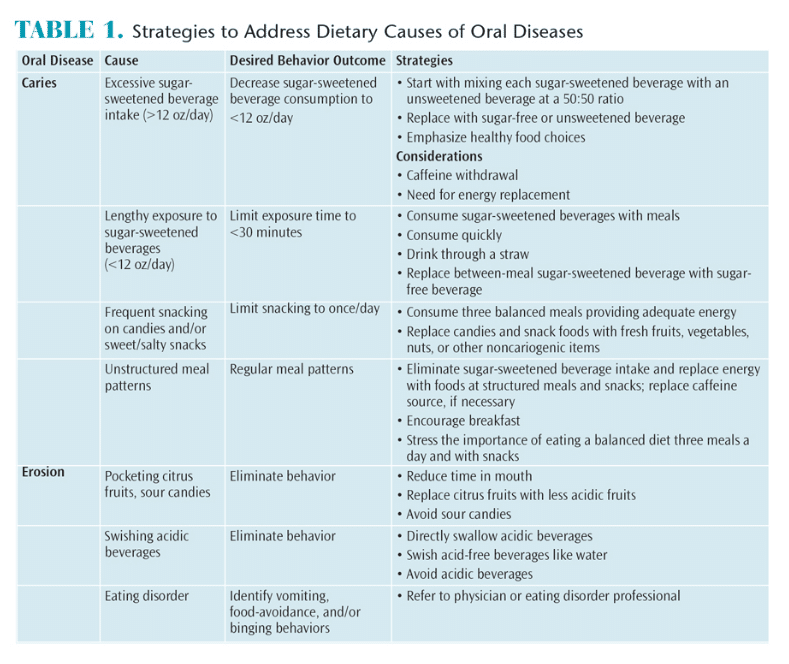

After identifying the oral health concern and the dietary contributors, nutritional strategies to address the disease and/or reduce risk of disease are presented (Table 1). Change is difficult for most individuals and multiple modifications are often required before an acceptable diet can be achieved. As such, the recommended strategies should be prioritized based on the most pressing health concerns. Patients should be provided with the desired behavior outcome and multiple strategies for achieving the outcome. Because foods are not consumed in isolation, a change in one area of the diet often impacts other areas of food and beverage consumption. Thus, additional strategies should be presented as anticipatory guidance (in advance of expected difficulties).22 Changing food choices and dietary behaviors is a gradual process and support is essential for success.

Dietary counseling is not simply telling patients what to do. In order to be effective, dietary counseling is a negotiation between the clinician and patient. Both the patient’s environment—including financial resources and food availability—and reserve capacity (ability to take on additional emotional or physical stress and make the required time commitment) will influence his or her ability to comply with the proposed dietary changes. The clinician’s responsibility is to identify the problem, educate the patient about the disease-diet relationship, and provide strategies to address the problem. Implementation of the strategies to reduce oral disease, however, is the patient’s responsibility. Both motivational interviewing and self-determination theory are appropriate counseling approaches to assist patients in achieving dietary change.23

Dental hygienists are responsible for providing dietary counseling for oral health and oral disease prevention consistent with ChooseMyPlate recommendations. However, some patients will present with systemic diseases or educational or resource limitations that hinder dental hygienists’ abilities to address these problems. In these situations, dental hygienists should refer patients to an appropriate health care provider, such as registered dietitians, state cooperative extension specialists, or local food/nutrition educators. Patients with resource limitations should be apprised of food assistance programs, local food banks, and/or free meal programs.

CONCLUSION

As members of the oral health care team, dental hygienists are well positioned to identify dietary contributors to oral and systemic disease. Understanding the relationships between oral disease, nutritional intake, and dietary behaviors is the foundation for patient education. Performing nutrition assessments to identify diet-related risk factors and providing counseling or referrals to help patients address the identified risk factors are necessary to improve both oral and systemic health.

References

- Marshall TA. Preventing dental caries associated with sugar-sweetened beverages. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:1148–1152.

- Marshall TA. Nomenclature, characteristics, and dietary intakes of sugars. J Am Dent Assoc. 2015:146:61–64.

- Al-Khatib GR,Duggal MS, Toumba KJ. An evaluation of the acidogenic potential of maltodextrins in vivo. J Dent. 2001;29:409–414.

- Marshall TA, Levy SM, Broffitt B, et al. Dental caries and beverage consumption in young children. Pediatrics. 2003;112:e184–e191.

- Palmer CA, Kent R, Loo CY, Hughes CV, et al. Diet and caries-associated bacteria in severe early childhood caries. J Dent Res. 2010;89:1224–1229.

- Evans EW, Hayes C, Palmer CA, Bermudez OI, Cohen SA, Must A. Dietary intake and severe early childhood caries in low-income, young children. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113:1057–1061.

- Marshall TA, Broffitt B, Eichenberger-Gilmore J, Warren JJ, Cunningham MA, Levy SM. The roles of meal, snack, and daily total food and beverage exposures on caries experience in young children. J Public Health Dent. 2005;65:166–173.

- Mallonee LFH, Boyd LD, Stegeman C. Practice Paper of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Oral Health and Nutrition. 2014;114(6):958.

- Ehlen LA, Marshall TA, Qian F, Wefel JS, Warren JJ. Acidic beverages increase the risk of in vitro tooth erosion. Nut Res. 2008;28:299–303.

- Wagoner SN, Marshall TA, Qian F, Wefel JS. In vitro enamel erosion associated with commercially available original-flavor and sour versions of candies. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:906–913.

- Moynihan PJ. Update on nutrition and periodontal disease. Quintessence Int. 2008;39:326–330.

- Kaye EK. Nutrition, dietary guidelines and optimal periodontal health. Periodontol 2000. 2012;58:93–111.

- Maffeis C, Silvagni D, Bonadonna R, Grezzani A, Banzato C, Tato L. Fat cell size, insulin sensitivity, and inflammation in obese children. J Pediatr. 2007;151:647–652.

- Reeves AF, Rees JM, Schiff M, Hujoel P. Total body weight and waist circumference associated with chronic periodontitis among adolescents in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:894–899.

- Morita I, Okamoto Y, Yoshii S, et al. Five-year incidence of periodontal disease is related to body mass index. J Dent Res. 2011;90:199–202.

- Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Oral Health and Nutrition. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013:113:693–701.

- United States Department of Agriculture and Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7th ed. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2010.

- US Department of Agriculture and Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015-2020. Available at: health.gov/ dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines. March 9, 2016.

- US Department of Agriculture. ChooseMyPlate. Available at: choosemyplate.gov. Accessed March 9, 2016.

- Corkins KG. Nutrition-focused physical examination in pediatric patients. Nutr Clin Pract. 2015;30:203–209.

- Radler DR, Mobley C. Obesity and oral health across the lifespan. In: Touger-Decker R, Mobley C, Epstein JB, eds. Nutrition and Oral Medicine. 2nd ed. New York: Humana Press; 2014.

- Marshall TA. Chairside diet assessment of caries risk. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:670–674.

- Patrick H, Williams GC. Self-determination theory: its application to health behavior and complementarity with motivational interviewing. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;2;9–18.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2016;14(04):48–51.