MONKEY BUSINESS IMAGES LTD / MONKEY BUSINESS / THINKSTOCK

MONKEY BUSINESS IMAGES LTD / MONKEY BUSINESS / THINKSTOCK

Screening for Suicide May Save a Life

Oral health professionals are well positioned to screen for this preventable cause of death during the dental hygiene process of care.

This course was published in the April 2016 issue and expires April 20, 2019. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss who is at greatest risk of suicide.

- Identify the risk factors associated with suicide.

- Explain the strategies that can be implemented when the risk of suicide is noted in a patient.

- List additional resources for training in suicide screening.

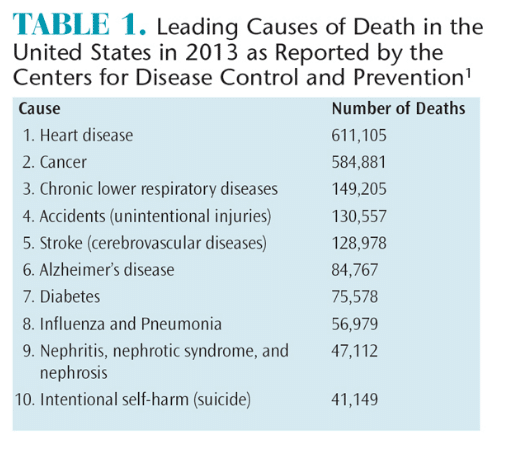

An estimated 804,000 deaths were caused by suicide across the globe in 2012, and in 2013 suicide was the tenth leading cause of death in the United States.1,4 The US Surgeon General’s National Strategy for Suicide Prevention specifies that for each individual whose life is claimed by suicide, 30 others make suicide attempts.5

In the US, suicide death rates for men and boys are roughly four times higher than those for women and girls, with men and boys representing 77.9% of all suicides.1 Over the past decade (2005-2014), suicide has been the second leading cause of death for all men and boys between the ages of 10 and 44. Among men and boys between the ages of 10 and 34, suicide accounts for more deaths than cancer and heart disease combined.1 Women and girls, however, experience suicidal thoughts more often than men and boys. Men and boys most often use firearms to commit suicide, while women and girls are more likely to ingest poison.1

Young adults are at increased risk of suicide. Adults age 18 to 25 were most likely to have serious thoughts about suicide (7.4%) compared with those age 26 to 49 (1.35%) and those age 50 and older (0.6%).1 In 2015, among adolescents in grades 9 to 12, approximately 17% contemplated suicide; 13.6% made plans for ending their lives; and 8% attempted suicide at least once.1

Race and ethnicity are tied to suicide risk. American Indians/Alaskan Natives have the highest rates of suicide compared with any other ethnic group. Suicide is the second leading cause of death among American Indians/Alaskan Natives age 10 to 34. Hispanics are also at increased risk of suicide. Among Hispanic students age 14 to 18, the rates of seriously considering a suicide attempt, making plans to attempt suicide, and attempting suicide were higher than both whites and blacks.6

Suicide has a tremendous impact on society and survivors. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, medical and work-loss costs related to suicide are estimated at $44.6 billion per year.7 When an individual attempts or achieves suicide, his or her friends, family, acquaintances, and coworkers are also affected. Survivors are at increased risk of suicide themselves.7,8 They may also experience feelings of guilt, anger, abandonment, denial, helplessness, and shock.7,9,10

Many risk factors are associated with suicide, but there is no single cause. As such, there is no one prevention intervention that will prevent suicide.5 The risk factors associated with suicide, however, can be identified in the dental setting, as well as in clinicians’ personal and professional circles.

IDENTIFICATION OF RISK FACTORS

Dental hygienists often have a rapport with patients, providing opportunities to screen for risk factors associated with suicide. Clinicians can look for unexplained cuts, scratches, bruises, or burns on the body—particularly on the wrist and forearms; traumatic gingival lesions not consistent with dental health/occlusion; unexplained loss of teeth; and signs of pulling hair or removing eyelashes. These may be signs that a patient is purposely harming him or herself.11 A previous suicide attempt is a major risk factor.4

During the health history review, risk factors such as alcohol abuse, mental health disorders, and chronic pain can be identified.4 Depression, which is a significant risk factor for suicide, may also be discovered from the health interview. However, patients may not have received a diagnosis or list depression on their health history forms.

Clinical depression is one of the most common mental health disorders. Its impact on society may be underestimated due to the fact that depression often accompanies other medical problems, increasing the likelihood that it will be downplayed or overlooked.12 Mental health professionals in the US use the standard classification of mental disorders from the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). The diagnostic criteria for severe depression are met when at least five of the following are present most of the day, nearly every day for a minimum of 2 weeks:12

- Sadness

- Loss of interest or pleasure in usual activities

- Changes in appetite (increased or decreased)

- Weight change

- Disturbed sleep (insomnia or hypersomnia)

- Psychomotor disturbances

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feelings of guilt or self-blame

- Decreased ability to concentrate or make decisions

- Thinking about or planning suicide or suicidal behavior

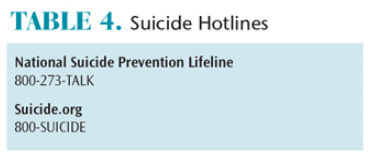

In addition to the diagnostic criteria outlined for depression in the DSM-5, other forms of depressive disorders are recognized by the National Institute of Mental Health, including major depression, persistent depressive disorder, psychotic depression, post-partum depression, seasonal affective disorder, and bipolar disorder (Table 2).13 If a patient reports symptoms related to the varying forms of depressive disorders or expresses at least five of the criteria outlined in the DSM-5 for most of the day, nearly every day for a period of at least 2 weeks, referring him or her for an evaluation by a qualified mental health professional is appropriate.

A patient’s social history may also provide clues for increased suicide risk. Individuals who have experienced discrimination, isolation, abuse, violence, conflictual relationships, financial problems, loss of a friend or family member to suicide, military service past or present, or psychological stress may be at increased risk.4 By recognizing risk factors, clinicians can encourage patients to seek treatment or support from mental health professionals, so that further suicide prevention strategies can be implemented.

CASE STUDY

A 35-year-old married man who has been receiving care in the practice for at least 10 years discloses to the dental hygienist during his recare appointment that he is going through an unwanted divorce. A police officer, he admits that after slapping his wife in an argument, his department is conducting an investigation into a possible domestic violence charge. He may lose his job. The patient seems tearful, but controls himself. At the end of the procedure he says, “Tell Dr. Smith he has been terrific to me. I’m heading up to my cabin one more time.”

Dental hygienist: “What you said concerns me, and I am worried for your safety. Given what you are going through, you sound pretty hopeless.”

Patient: “Wouldn’t you be?”

Dental hygienist: “Probably. Sometimes when people feel hopeless they also have thoughts of suicide. Have you had any of those?”

Patient: “Yes.”

Dental hygienist: “We have some excellent people on hand who could talk to you about what you’re going through. Would you like me to call one of them? I can do it right now.”

Patient: “I guess that would be OK.”

TAKING ACTION

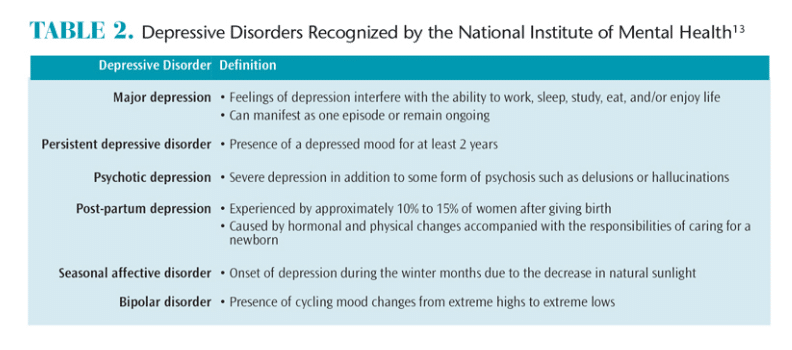

Receiving additional training on suicide prevention may be helpful for nonmental health professionals. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration supports the Suicide Prevention Resource Center (sprc.org/bpr).14 The center provides a list of evidence-based programs for suicide intervention training and/or certification. Table 3 also lists some of the education and training programs that can help dental professionals further identify, review, and disseminate information about best practices in suicide prevention. This type of training provides participants with the ability to recognize warning signs of suicide, the questions to ask to assess an individual’s status, techniques to persuade him or her to seek help, and appropriate referrals to mental health professionals.15

The warning signs of suicide should elicit a response similar to when a patient advises the clinician that he or she has a history of rheumatic heart disease, which, of course, changes the protocol for patient management immediately. The rule of thumb for suicide gatekeepers is if there is any doubt whether a patient is potentially suicidal, questions should be asked to clarify the patient’s intent. While taking this step is uncomfortable for most, oral health care professionals can effectively question the patient either directly or indirectly based on the warning signs and the nature of the conversation to better assess the patient’s risk status. See the case study for a sample conversation.

If the patient’s responses satisfy the oral health professional that he or she is not at serious risk for suicide, the intervention is complete. The clinician can simply let the patient know that he or she wanted to ensure the patient was fine. On the other hand, if the patient’s answers strengthen the concern or confirm a suicidal intent, the clinician then needs to empathetically try to persuade the individual to seek help and not give up hope. Growing evidence supports this act of showing concern, caring, and offering hope by asking, listening and encouraging individuals to seek help can be lifesaving.16 Oral health professionals should have an accessible and prescreened network of mental health providers who will promptly accept referrals of those identified to be at risk for suicide.

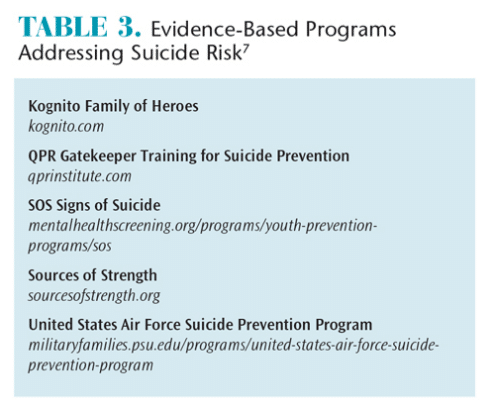

Developing a mental health support network is an essential requirement of a dental practice committed to suicide prevention. Assembling it can be challenging. A good start is to conduct a search of the mental health services and social services located in the county where the dental practice is located. Call-in hotlines such as those noted in Table 4 are not ideal referrals, but they can help to avert a crisis until face-to-face support is arranged. For at-risk dental patients who are younger than 18, clinicians must notify their parents/caregivers of suicide concerns. For adults, asking a patient’s permission to share the need for mental health referral with family members or friends is important, but if the patient does not agree, ensuring that he or she is committed to accepting such a referral is critical.

Even when oral health professionals develop a strong referral network, many at-risk individuals will still need assistance and follow-up to ensure they connect with mental health professionals. If the patient rejects the referral and suicidal intentions appear imminent, calling an emergency mental health unit for an evaluation may be justified.

The details of a suicide intervention occurring in the private-practice setting should be documented in the patient’s record. This not only provides an accurate record of care, but is also important when following up. Documentation of the intervention should include the identification of the suicide risk, referral sources recommended, and follow-up instructions. Personal follow up and continuity of care supports adherence to the suicide prevention program, which can be a powerful tool in preventing suicide attempts and deaths.17

LEARN MORE

The provision of dental hygiene services provides an opportunity to build partnerships. The patient and clinician partnership can be strengthened by the clinician’s investment in the patient’s total health including oral, physical, and mental health. Oral health practitioners can expand their interprofessional collaborations to include mental health professionals. Together, oral health professionals can join forces with mental health professionals to recognize risk factors associated with suicide, complete training for implementing strategies to prevent suicide, construct an office protocol for use when suicide risk is detected, develop a local mental health support system, and respond to the signs of suicide. These skills enable clinicians to screen for suicide risk during the dental hygiene process of care with the ultimate goal of saving lives that may have been lost to this preventable cause of death.

References

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury Prevention and Control: Data and Statistics (WISQARS). Ten Leading Causes of Death and Injury. Available at: cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/ LeadingCauses.html. Accessed March 17, 2016.

- Coombs DW, Miller HL, Alarcon R, Herlihy C, Lee JM, Morrison DP. Presuicide attempt communications between parasuicides and consulted caregivers. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1992;22:289–302.

- Robins E, Gassner S, Kayes J, Wilkinson RH, Murphy GE. The communication of suicidal intent: a study of 134 consecutive cases of successful (completed) suicides. Am J Psychiatry. 1959;115:724–733.

- World Health Organization. Preventing Suicide a Global Imperative. Available at: who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/world_report_2014/en/. Accessed March 17, 2016.

- Office of the Surgeon General. National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action, 2012. Available at: surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/national-strategy-suicide-prevention/. Accessed March 17, 2016.

- Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2013. MMWR Suppl. 2014;63:1–168.

- US Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide and Suicide Attempts Take an Enormous Toll on Society. Available at:?cdc.gov/violenceprevention/suicide/consequences.html. Accessed March 17, 2016.

- Brent D. What family studies teach us about suicidal behavior: implications for research, treatment, and prevention. Eur Psychiatry. 2010;25:260–263.

- Jordan JR. Is suicide bereavement different? A reassessment of the literature. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2001;31:91–102.

- American Association for Suicidology. Surviving After Suicide Factsheet. Available at:?suicidology.org/ Portals/14/docs/Resources/FactSheets/SurvivingAfterSuicide.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2016.

- Achal KS, Shute J, Gill DS, Collins JM. The role of the general dental practitioner in managing patients who self-harm. Br Dent J. 2014;217:503–506.

- Dobson KS, Dozois DJA. Risk Factors in Depression. Atlanta: Academic Press; 2008:17.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Depression. Available at: nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/ depression/index.shtml. Accessed March 17, 2016.

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center. Best Practices Registry. Available at: sprc.org/bpr/section-i-evidence-based-programs. Accessed March 17, 2016.

- QPR Institute. What is QPR? Available at: qprinstitute.com/about-qpr. Accessed March 17, 2016.

- Walrath C, Garraza LG, Reid H, Goldston DB, McKeon, R. Impact of the Garrett Lee Smith Youth Suicide Prevention Program on suicide mortality. Am J Public Health. 2015:105:986–993.

- American Association of Suicidology, Suicide Prevention Resource Center University of Michigan Health System. Continuity of Care for Suicide Prevention and Research. Suicide Attempts and Suicide Deaths Subsequent to Discharge from an Emergency Department or an Inpatient Psychiatric Unit. Available at: sprc.org/sites/sprc.org/files/library/continuityofcare.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2016.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2016;14(04):52–55.