Strategies for Managing Patients With Special Needs and Disabilities

Through behavioral techniques and treatment modifications, this population can successfully receive much-needed dental care.

This course was published in the November/December 2023 issue and expires December 2026. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 750

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define the challenges faced by individuals with special healthcare needs and disabilities (SHCND).

- DIdentify behavioral modification techniques that can be used when patients with SHCND seek dental care.

- D Note treatment modifications that oral health professionals can employ when treating patients with SHCND.

People with special healthcare needs and disabilities (SHCND) often face greater challenges to accessing healthcare and significant health inequities than those without disabilities.1 According to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a disability is an impairment of the body or mind that makes it more difficult to engage in activities and participate in day-to-day life.2 Individuals with SHCND experience long-term physical, behavioral, developmental, and emotional conditions, such as Down syndrome, autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, cerebral palsy, and epilepsy, that require special attention and medical care.3,4

Approximately 1.3 billion people, or nearly 16% of the world’s population, have a disability.5 For about 190 million individuals, the disability is severe such as quadriplegia, blindness, or severe depression.6 Additionally, one in four Americans has a disability.7 The 2005-2006 National Health Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs found that 13.9% of US children have special healthcare needs and 21.8% of households with children included at least one child with a special healthcare need.8 The presence of any of these types of special needs and/or disabilities limits the ability of individuals to access preventive dental and medical services.

Numerous epidemiological host and environmental factors influence the dental disparities often faced by those with SHCND. Access to care and high costs hinder the goal of improving the oral health of the SHCND population.9 In an Australian study that investigated the association between dental attendance and disability status, irregular dental attendance was 1.4 times greater among those with a disability than those without a disability.10

With irregular dental attendance comes greater risks of dental caries and periodontal diseases.10 Additionally, healthcare costs are three times higher for children with SHCND than typical children.8 High costs inhibit accessibility, leading to negative health effects. For example, children with Down syndrome often have open bite and dysphagia, increasing the risk for caries and plaque and calculus formation.4 Treatable dental conditions are often neglected in this population, resulting in further debilitation and decreased overall health.11

Managing patients with SHCND in the dental setting can be challenging. Research has shown that dentists feel they lack the knowledge or tools necessary to successfully treat this population, limiting the number of dental providers willing to care for patients with SHCND.12,13

People with SHCND may need extra help to maintain good oral health. Multiple health challenges and neuromuscular problems may interfere with proper oral self-care. Individuals with physical and mental disabilities may have difficulty brushing their teeth and may not grasp the importance of oral hygiene.14 Those with uncontrolled body movements can make it difficult to provide dental care. Furthermore, patients with SHCND are sometimes unable to communicate their oral health needs.14 Thus, ensuring that this population maintains good oral and systemic health requires collaboration among caregivers, family members, and dental/healthcare professionals.

Behavioral Modification Techniques

Implementing behavioral models, such as the health belief model, to manage patients with SHCND can help improve this population’s oral health. The health belief model is a social cognitive approach to elicit behavioral changes and predict behaviors related to health. The model consists of six components:15

- Risk susceptibility

- Risk severity

- Benefits to action

- Barriers to action

- Self-efficacy

- Cues to action

The health belief model suggests that a health behavior is influenced by an individual’s susceptibility to the disease, how the severity of the disease is perceived, how barriers to the behavior change are viewed, and how the benefits to the behavior change are seen. For the implementation of a specific behavior to be successful, the perceived threat of the disease and benefits of a health behavior must prevail over the perceived barriers.16

Use of the health belief model has proven to be effective in reducing caries among adolescents and those with SHCND.17,18 For patients with SHCND, parents/caregivers and the patients themselves must perceive dental caries and other oral diseases as severe enough to adopt behaviors that can aid in disease prevention. This can be done through effective oral health education interventions at an early age.

Pre-dental visit meetings between oral health professionals and parents/caregivers to discuss potential areas of concern and identify their health beliefs can be valuable to the dental team.19 Children as young as age 6 are able to comprehend information that form their health beliefs.20 Instilling positive attitudes toward oral health behaviors at an early age can aid in the prevention of dental caries and future oral health complications.17

Another behavioral modification technique that can be used when treating patients with SHCND is modeling. This entails asking a patient to watch another patient who is undergoing treatment. The modeling can be live or filmed, and the model can be cooperative at the start of treatment or fearful at the start, learning to cope during treatment. The model can present with similar characteristics relative to the patient observing; the patient watching the model can be active or passive. Previous research has found that modeling has been effective, although further study is needed to determine its efficacy among patients with SHCND.21

The use of positive reinforcement is another tool that can be used during dental visits for patients with SHCND. This technique introduces a desirable or favorable stimulus following a specific behavior. The behavior is reinforced by the desirable stimulus, making it more likely the behavior will continue.22

The operant conditioning model includes both positive and negative reinforcement. This is in contrast to negative reinforcement where the undesirable stimulus is removed to encourage the behavior.23 For patients with SHCND who struggle with cooperation in a dental environment, tokens of appreciation and words of encouragement can help to elicit a desired behavior.18 Parents/caregivers who are present during procedures are positive reinforcers.19 Parents/caregivers can also support patient compliance, decrease negative behaviors, and facilitate successful communication between the patient and the dental team.19

The transtheoretical model (TTM) and motivational interviewing are techniques used to elicit behavioral change among patients with SHCND. Based on the premise that changing a behavior is a process and individuals are in various stages of readiness to change, the TTM has five stages:25–27

- Precontemplation

- Contemplation

- Preparation

- Action

- Maintenance

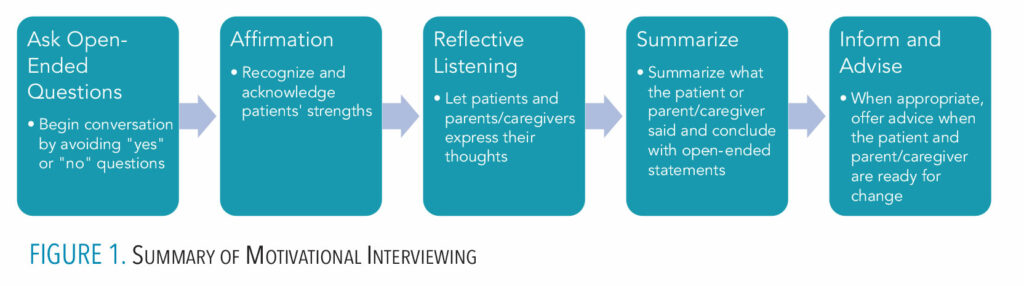

The stages of change in the TTM are fundamental to the foundation of motivational interviewing. Motivation is what drives the stages of change, and the use of motivational interviewing can assist individuals to accomplish the various tasks required to transition from the precontemplation stage through the maintenance stage (Figure 1, page 33).26

Asking open questions, affirming, reflective listening, summarizing, and informing and advising are five core skills in motivational interviewing.27 The use of motivational interviewing has shown to be effective in helping patients to reach the maintenance stage.28 Most important, the dental team can use motivational interviewing by collaborating with patients and parents/caregivers through open and consistent communication. Research has shown that motivational interviewing helped patients with SHCND and their parents/caregivers to increase their frequency of toothbrushing.24

the fear and anxiety felt by patients with special

healthcare needs and disabilities.

Modifications During Dental Care

Patients with SHCND may require modifications when undergoing dental treatment. Various techniques, such as “tell-show-do” may help ensure the necessary procedure is completed (Figure 2). Prior to initiating a dental procedure, the clinician thoroughly informs the patient about the procedure and demonstrates it.29 The goal is to reduce the fear associated with the dental procedure and ease the anxiety often felt by patients with SHCND.

The use of social stories has been successful in producing positive results in children with autism spectrum disorder.30 Developed in 1990 by Carol Gray, a social story is a pictorial narrative used to demonstrate situations and problems and how to cope with them. The stories help children with autism spectrum disorder communicate and know what to expect during a dental visit. For patients with SHCND, social stories can be created in a comic strip format and shown prior to the procedure. The stories include basic cooperative sentences to help the patient understand how the dental team plays an important role in providing treatment.31 With each picture, the patient with SHCND can begin to recognize the reasons behind performing procedures in a simple approach.

provided with weighted blankets, is helpful in

supporting patients with special needs during

dental appointments.

Devices can be beneficial during treatment of patients with SHCND. The dental team can apply deep touch pressure, a sensory adaptation technique.32 Examples include protective stabilization immobilization devices that are specialized for each patient and weighted blankets (Figure 3).33 The use of this sensory adaptation technique can ease anxiety. Additionally, the use of disposable bite sticks can aid the dental provider with oral accessibility during examinations and treatment.32 Studies have shown the disposable bite sticks have significantly improved oral access and examination quality while also being well-tolerated by patients with SHCND.34

Public Health Implications

Treating people with SHCND is a public health problem that needs significant attention to reduce barriers to oral and medical care.8 Oral health disparities, such as those often experienced by patients with SHCND, must be addressed through research, policy, and practice. Health policies to improve access to care can be an effective means for improving oral health and overall health. The Oral Health In America: Surgeon General Summary suggests creating a national oral health plan to include an “effective health infrastructure that meets the oral health needs of all Americans and integrates oral health effectively into overall health.”35 This population often requires special consideration when receiving dental treatment because of their physical or developmental conditions.34 Dental practices must meet obligations under the Americans with Disabilities Act, and other local, state, and federal disability laws.36

Oral health professionals’ lack of competence and willingness to treat patients with SHCND profoundly impacts this population’s ability to access dental care and maintain oral health.37 Currently, the Commission on Dental Accreditation has instituted new requirements for dental schools to educate their students on treating patients with SHCND.37 The use of behavioral models and devices for patients with SHCND may increase the likelihood of successful dental treatment while boosting oral health professionals’ confidence to care for this population.

References

- Okoro CA, Hollis ND, Cyrus AC, Griffin-Blake S. Prevalence of disabilities and health care access by disability status and type among adults — United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:882-887.

- United States Centers for Disease and Prevention. Disability and Health Overview. Available at: cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/disability.html. Accessed October 19, 2023.

- Bastani P, Mohammadpour M, Ghanbarzadegan A, Rossi-Fedele G, Peres MA. Provision of dental services for vulnerable groups: a scoping review on children with special health care needs. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:1302.

- Ningrum V, Bakar A, Shieh TM, Shih YH. The oral health inequities between special needs children and normal children in asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare. 2021;9:410.

- World Health Organization. Disability and Health. Available at: who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health. Accessed October 19, 2023.

- World Health Organization. World Report on Disability 2011. Available at: ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK304067. Accessed October 19, 2023.

- Healthy People 2030. People With Disabilities. Available at: health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/people-disabilities. Accessed October 19, 2023.

- Waldman HB, Perlman SP, Rader R. Hardships of raising children with special health care needs (a commentary). Soc Work Health Care. 2010;49:618-629.

- Alamri H. Oral care for children with special healthcare needs in dentistry: a literature review.J Clin Med. 2022;11:5557.

- Lopez Silva CP, Singh A, Calache H, Derbi HA, Borromeo GL. Association between disability status and dental attendance in Australia—a population‐based study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2021;49:33-39.

- Lim MAWT, Borromeo GL. Oral health of patients with special needs requiring treatment under general anaesthesia. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability. 2018;44(3):315-320.

- Balkaran R, Esnard T, Perry M, Virtanen JI. Challenges experienced in the dental care of persons with special needs: a qualitative study among health professionals and caregivers. BMC Oral Health. 2022;22:1

- Alumran A, Almulhim L, Almolhim B, Bakodah S, Aldossary H, Alakrawi Z. Preparedness and willingness of dental care providers to treat patients with special needs. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2018;10:231-236.

- Uwayezu D, Gatarayiha A, Nzayirambaho M. Prevalence of dental caries and associated risk factors in children living with disabilities in Rwanda: a cross-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2020:36:193.

- Jones CL, Jensen JD, Scherr CL, Brown NR, Christy K, Weaver J. The Health Belief Model as an explanatory framework in communication research: exploring parallel, serial, and moderated mediation. Health Commun. 2015;30:566-576.

- Etheridge JC, Sinvard RD, Brindle, ME. Chapter 90. Implementation research. In: Eltorai AEM, Bakal JA, Newell PC, Osband AJ, eds. Translational Surgery. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Academic Press Inc; 2023:563-573.

- Sanaeinasab H, Saffari M, Taghavi H, et al. An educational intervention using the health belief model for improvement of oral health behavior in grade-schoolers: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Oral Health. 2022;22:1.

- Wilson NJ, Lin Z, Villarosa A, et al. Countering the poor oral health of people with intellectual and developmental disability: a scoping literature review. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1.

- Chandrashekhar S, Bommangoudar J. Management of autistic patients in dental office: a clinical update. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2018;11:219-227.

- Pandey R, Mishra A, Chopra H, Arora V. Oral health awareness in school-going children and its significance to parent’s education level. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2018;36:120-124.

- Kemp F. Alternatives: a review of non-pharmacologic approaches to increasing the cooperation of patients with special needs to inherently unpleasant dental procedures. The Behavior Analyst Today. 2005;6(2):88-108.

- Ackerman C. Positive reinforcement in psychology. Available at: positivepsychology.com/positive-reinforcement-psychology. Accessed October 19, 2023.

- McLeod S. What is operant conditioning and how does it work? Available at: simplypsychology.org/operant-conditioning.html. Accessed October 19, 2023.

- Bem JSP, dos-Santos DCG, de-Lima MG, et al. Effectiveness and legitimacy of the motivational interviewing with caregivers on the oral health of special patients. International Journal of Odontostomatology. 2021;15(2):466-472.

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Transtheoretical therapy: toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice. 1982;19(3):276-288.

- DiClemente C, Velasquez M. Motivational interviewing and the stages of change. In: Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2002:201-216.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2002.

- Kapoor V, Gupta A, Arya V. Behavioral changes after motivational interviewing versus traditional dental health education in parents of children with high caries risk: Results of a 1-year study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2019;37:192.

- Tyagi R, Gupta K, Khatri A, Khandelwal D, Kalra N. Control of anxiety in pediatric patients using “tell show do” method and audiovisual distraction. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2018;19:1058-1064.

- Zhou N, Wong HM, McGrath C. Efficacy of social story intervention in training toothbrushing skills among special‐care children with and without autism. Autism Res. 2020;13:666–674.

- Tobik A. Social stories for autistic children. Available at: autismparentingmagazine.com/social-stories-for-autistic-children. Accessed October 19, 2023.

- Chen HY, Yang H, Chi HJ, Chen HM. Physiologic and behavioral effects of papoose board on anxiety in dental patients with special needs. J Formos Med Assoc. 2019;118:1317-1324.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Use of protective stabilization for pediatric dental patients. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. Chicago: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2022:340–346.

- Mogenot M, Hein-Halbgewachs L, Goetz C, et al. Efficacy, tolerability, and safety of an innovative medical device for improving oral accessibility during oral examination in special-needs patients: a multicentric clinical trial. PloS One. 2020;15:e0239898.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges. Available at: cdc.gov/oralhealth/publications/federal-agency-reports/OHA2021.html. Accessed October 19, 2023.

- American Dental Association. Special Considerations for Patients. Available at: ada.org/en/resources/practice/practice-management/special-considerations. Accessed October 19, 2023.

- Commission on Dental Accreditation Accreditation. Standards for Dental Education Programs. Available at: coda.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/coda/files/predoc_standards.pdf?rev=20eabc229d4c4c24a2df5f65c5ea62c8&hash=B812B8A2FAF6D99F37703EE081B48E58. Accessed October 19, 2023.

From Dimensions in Dental Hygiene. November/December 2023; 21(10):32-35