Quelling Dental Anxiety

A variety of techniques is available to help fearful patients experience successful dental appointments.

This course was published in the November 2014 issue and expires November 30, 2017. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss different types of anxiety.

- Recognize the signs and symptoms of fearful patients.

- Identify the causes of dental anxiety and the results of untreated dental fear.

- Describe the various methods of management for fearful dental patients.

Dental anxiety is prevalent among the general population, and is linked to the avoidance of dental care and poor oral health. As such, addressing dental anxiety should be a priority for oral health professionals. Dental hygienists are in a unique position to help reduce the anxiety of patients in order to support their oral and systemic health.

Occasional anxiety is a normal part of life. People with anxiety disorders, however, experience intense fear about everyday situations. There are several types of anxiety disorders that affect a variety of populations (Table 1).

In Western societies, 16% to 40% of the adult population report fear of dental treatment, known as dental anxiety. Within this group, 3% to 5% exert signs of dental phobia.1 Among individuals with dental phobia, the thought of a dental visit causes severe panic. Dental phobia is described as an intense, unreasonable fear that often causes avoidance of dental care for years. Signs and symptoms of dental phobia include, but are not limited to: sweating, difficulty breathing, rapid heart rate, feelings of panic, intense anxiety, and avoidance.

Despite modern oral health treatment techniques, dental anxiety disorders remain one of the most widespread health-related problems.2 This article will focus on dental anxiety, as dental phobias affect a small percentage of the population and the literature base on this topic is limited.

ETIOLOGY OF DENTAL ANXIETY AND FEARS![]()

People develop dental fears for many reasons. The development of anxiety or phobia may be due to direct or indirect learning from negative experiences. Individuals may have experienced pain during treatment, witnessed a traumatic dental experience, or heard about someone else’s traumatic dental experience.3–8 For example, parents discussing their dental fears with their children may lead them to develop anxiety about oral health care.9 Some individuals with dental anxiety, however, cannot recount a traumatic story that would explain their dental fear.10 The anxiety may be a result of subjective perceptions of the behavior of dental professionals or the patient feeling a lack of control during dental procedures.11–14

NEGATIVE EFFECTS OF DENTAL ANXIETY AND FEARS

Severe dental anxiety may significantly impact individuals’ quality of life. Those with dental anxiety are more likely to have poor oral health, with pain caused by the prolonged avoidance of dental care. The anxiety may also impair their health-related quality of life, and lead to general anxiety or avoidance of social contact.15

Individuals with dental anxiety tend to have poor oral hygiene—likely because of an association between negative feelings and oral hygiene practices, as well as the fact that they don’t receive professional oral health education due to their avoidance of dental care.16 Patients with dental anxiety tend to avoid seeking professional dental care unless they develop severe oral pain.

A high number of decayed and missing teeth has been reported among individuals with dental anxiety.17 The lack of routine dental care may result in conditions that can no longer be treated with routine restorative or periodontal treatment, leaving extraction as the sole option. Patients with missing teeth are more likely to consume a poor diet, and experience reduced social interaction and communication due to their appearance.18

ROLE OF THE DENTAL PROFESSIONAL

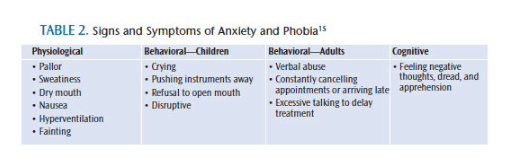

Recognizing anxiety and fear in dental patients is an important part of overall patient management. Careful observation by the dental professional allows for proper identification of these conditions. The simplest way to monitor anxiety is through self-report. Ask patients if they are experiencing feelings of anxiety. A questionnaire may also be provided to elicit this information. Table 2 provides a list of signs and symptoms of anxiety and phobia.15

It is important to match anxiety management practices to individual patient needs. The majority of patients will exhibit mild to moderate feelings of fear. Approaches to treat this level of anxiety without other complications are relatively simple. The dental hygienist may play a direct or indirect role in the management of fear. A variety of methods are available to manage dental anxiety or phobias that are used alone or in combination. These methods include pharmacological, behavioral, and psychological approaches.15 Reducing dental fear must come from the mutual efforts of both the patient and the dental practitioner to make the treatment proceed smoothly.

![]() PHARMACOLOGICAL APPROACH

PHARMACOLOGICAL APPROACH

Pharmacological support may consist of conscious sedation, inhalation sedation, intravenous sedation, or general anesthesia.15 Pre- and post-medication can facilitate care and patient comfort, but behavioral and psychological techniques are preferred to provide patients with a means of control that can be applied not only in the dental office, but in other settings, as well.

BEHAVIORAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL APPROACHES

A variety of behavioral and psychological approaches is available to help build trust and rapport in patients with the goal of relieving dental fear.15,19 First, communication is crucial. Verbal communication by the dental practitioner should include a reassuring tone of voice and greeting the patient by name. The patient should be asked about feelings of anxiety in a caring and friendly manner. Patient concerns should be genuinely acknowledged. Oral health professionals need to be attuned to nonverbal cues, listen closely to the patient, and accurately reflect what the patient says—all while demonstrating empathy.

Communicating with patients about their scheduling preferences is also recommended. Morning appointments are often best to prevent anxious patients from worrying about the appointment all day long and to prevent any unforeseen delays, which may agitate these individuals. Thoroughly explaining the procedure to the patient gives him or her a sense of predictability during the treatment.

Nonverbal communication is just as important as verbal communication in facilitating rapport and trust. This includes facial expressions, such as smiling, and positive body language and gestures. Encouraging patients to communicate nonverbally during treatment, such as signaling, provides them with a sense of control and engenders trust.

Using a motivational interviewing technique is also helpful. This approach focuses on exploring and resolving ambivalence and centers on motivational processes within the individual to facilitate change. It is a collaborative conversation to strengthen an individual’s motivation for and commitment to change to healthier behaviors—such as coming in for regular dental appointments and adhering to appropriate daily oral hygiene regimens. Motivational interviewing is based on the following principles: creating a rapport, discussing ambivalence, listening with reflection, evaluating readiness, accepting resistance or reinforcing positive choices, and enabling patient autonomy in decision making.20,21 For more information on this technique, visit motivationalinterviewing.org.

The tell-show-do method was originally developed to reduce fear in children, but it has also been applied to adults with dental anxiety. With this technique, dental professionals explain what they are going to do, show what is involved, and then perform the procedure. It is an interactive and communicative approach.

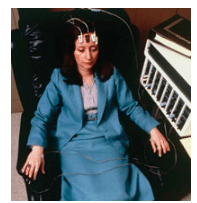

FIGURE 1. A woman undergoes biofeedback to reduce anxiety. ROBERT GOLDSTEIN/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Rest breaks can be helpful by allowing fearful patients to calm down enough to continue and complete treatments. The patient should not be rushed. Positive reinforcements can also create a more pleasant experience, whether physical, such as a sticker or toy for a child, or verbal praise.

The use of distractions, such as movies or music, can help redirect a patient’s focus from dental sounds, which may initiate anxiety. Encourage patients to bring their favorite movie or music to the appointment to give them a sense of control.

Breathing exercises appear to lower anxiety and perceived pain. Biofeedback, a method in which users learn to control their body’s responses, gives anxious individuals the opportunity to view their physiological responses to stress (Figure 1).22 Patients are fitted with electrical sensors that help provide feedback about their body, such as relaxing specific muscles, in order to implement changes that will reduce anxiety or pain.23 Biofeedback can help patients gain more control over normal involuntary functions, such as heart rate, breathing, skin temperature, muscle tension, and blood pressure. More research is needed to understand why biofeedback is effective. Several different relaxation exercises are used in biofeedback therapy, including: deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery, and mindfulness meditation.

Hypnosis is a state of consciousness involving focused attention and reduced peripheral awareness characterized by an enhanced capacity for response to suggestion. The patient is able to concentrate intensely on a specific thought or memory, while blocking out sources of anxiety.

Aromatherapy is a form of alternative medicine that uses plant materials and aromatic plant oils—including essential oils and other aromatic compounds—for the purpose of altering an individual’s mood or cognitive, psychological, or physical well-being (Figure 2). The oils can be diffused in the atmosphere to produce a calming effect for patients.

Acupuncture involves insertion of thin needles along specific points on the skin to stimulate nerves, muscles, and connective tissue. This technique is used to alleviate pain and treat various physical, mental, and emotional conditions.

Modeling is a technique that involves teaching patients about the situation by having them observe someone else. This technique is most frequently used for children, so they know what to expect in a dental visit.

CONCLUSION

Little is known about fearful patients’ perceptions of dental hygienists and dental hygiene care.23 The feel and sound of dental hygiene instruments, coupled with the patient’s perception that he or she has little control are important contributors to the fear of dental hygiene treatment.23 While dental fear presents a considerable barrier to care and impacts all dental professionals, this type of anxiety can be managed through a variety of methods and techniques. Oral health professionals must regard each patient as an individual, and tailor the management methods based on his or her specific needs. The personal and confidential relationship between a trusted dental care provider and his or her patient is vital to successful communication, effective provision of oral health education, and patient satisfaction with dental care.

REFERENCES

- Hultvall MM, Lundgren J, Gabre P. Factors of importance to maintaining regular dental care after a behavioural intervention for adults with dental fear: a qualitative study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2010;68:335–343.

- Margaritis V, Koletsi-Kounari H, Mamai-Homata E. Qualitative research paradigm in dental education: an innovative qualitative approach of dental anxiety management. J Int Oral Health. 2012;4:11–22.

- Bernstain DA, Kleinknecht RA, Alexander LD. Antecedents of dental fear. J Public Health Dent. 1979;39:113–124.

- Davey GCL. Dental phobias and anxieties: evidence for conditioning processes in the acquisition and modulation of learned fear. Behav Res Ther. 1989;27:51–58.

- Locker D, Shapiro D. Psychological factors and perceptions of pain associated with dental treatment. Community Dent Health. 1996;13:86–92.

- Maggirias J, Locker D. Psychological factors and perceptions of pain associated with dental treatment. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2001;30:151–159.

- De Jongh A, Aartman IHA, Brand N. Trauma-related phenomena in anxious dental patients. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31:52–58.

- De Jongh A, Fransen JB, Oosterink-Wubbe FMD, Aartman IHA. Psychological trauma exposure and trauma symptoms among individuals with high and low levels of dental anxiety. Eur J Oral Sci. 2006;114:286–292.

- Themessl-Huber M, Freeman R, Humphris G, MacGillivray S, Tezri N. Empirical evidence of the relationship between parental and child dental fear: a structured review and meta-analysis. Int J Paediatric Dent. 2010;20:83–101.

- Armfield JM. Towards a better understanding of dental anxiety and fear: cognitions vs. experiences. Eur J Oral Sci. 2010;118:259–264.

- Johansson P, Berggren U, Hakeberg M, Hirsch JM. Measures of dental beliefs and attitudes: their relationships with measures of fear. Community Dent Health. 1992;10:31–39.

- Kvale G, Berg E, Nilsen CM, et al. Validation of the dental Fear Scale and the Dental Belief Survey in a Norwegian sample. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25:160–164.

- Abrahammson KH, Beggren U, Hakeberg M, Carlsson SG. The importance of dental beliefs for the outcome of dental fear treatment. Eur J Oral Sci. 2003;111:99–105.

- Abrahammson KH, Hakeberg M, Stenman J, Ohrn K. Dental beliefs: evaluation of the Swedish version of the revised Dental Beliefs Survey in different patient groups and in a non-clinical student sample. Eur J Oral Sci. 2006;114:209–215.

- Rafique S, Fiske J. Special care: management of the petrified dental patient. Dent Update. 2008;35:196–207.

- DeDonno MA. Dental anxiety, dental visits and oral hygiene practices. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2012;10:129–133.

- Armfield JM, Slade GD, Spencer AJ. Dental fear and adult oral health in Australia. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37:220–230.

- McGrath C, Bedi R. The association between dental anxiety and oral health-related quality of life in Britain. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32: 67–72.

- Armfield JM, Heaton LJ. Management of fear and anxiety in the dental clinic: a review. Australian Dent J. 2013;58:390–407.

- Britt E, Hudson SM, Blampied NM. Motivational interviewing in health settings: a review. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;53:147–155.

- Wagner CC, Ingersoll KS. Beyond cognition: broadening the emotional base of motivational interviewing. J Psychotherapy Integ. 2008;18:191–205.

- Mayo Clinic. Biofeedback: Using Your Mind to Improve Your Health. Available at: mayoclinic.org/ testsprocedures/biofeedback/basics/definition/prc-20020004. Accessed October 21, 2014.

- Abrahammson KH, Stenman J, Ohrn K, Hakeberg M. Attitudes to dental hygienists: evaluation of the Dental Hygienists Beliefs Survey in a Swedish population of patients and students. Int J Dent Hyg. 2007;5:95–102.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November 2014;12(11):70–73.