Recognize Prader-Willi Syndrome

While this complicated genetic disorder may not be seen frequently in private dental practice, clinicians should be knowledgeable about its negative effects on the oral cavity.

This course was published in the November 2014 issue and expires November 30, 2017. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Describe the clinical signs and symptoms of Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS).

- Identify the incidence and prevalence of PWS in the United States.

- List the treatment considerations for patients with PWS.

- Discuss how dental hygienists can assist patients with PWS and their caregivers by providing an effective self-care regimen.

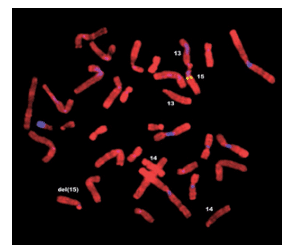

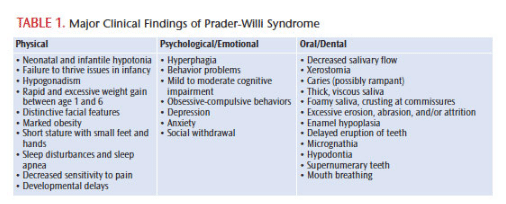

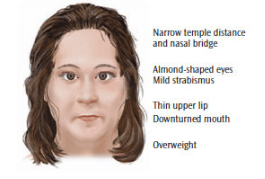

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is a rare genetic disorder. While its prevalence is low, PWS is the most common genetic human obesity syndrome. PWS is a multisystemic disorder that affects growth, eating patterns, metabolism, sexual development, cognitive function, and behavior. In the United States, the incidence of PWS is approximately one in 10,000 to 29,000 live births, and the prevalence is estimated at one in 52,000.1 PWS is found in all races and both sexes.1,2 The disorder is caused by a defect in specific regions of chromosome 15 (Figure 1). PWS causes neonatal and infantile hypotonia (poor muscle tone), feeding and weight gain concerns during infancy, rapid weight gain as toddlers, hyperphagia (food foraging and obsession with food), hypogonadism (low testosterone), developmental delays, intellectual disability, distinctive facial features, and certain oral and dental abnormalities (Table 1).1,3

PWS is caused by a spontaneous genetic error in which certain regions of chromosome 15q11 to 15q13 are deleted at the time of conception.1,2 In the majority of cases, crucial genes are simply lost or deleted from chromosome 15. In the remaining cases, the entire chromosome from the father does not present, and, as a result, the individual has two copies of chromosome 15 from the mother.2 Due to the missing genetic material, individuals with PWS have an improperly functioning hypothalamus, which controls feelings of hunger and fullness, growth and sexual development, motor function, and endocrine function, among others. The disruption in the normal function of the hypothalamus causes a continuous, uncontrollable urge to eat, sexual underdevelopment, and short stature. Morbid obesity due to hyperphagia (abnormally increased appetite) is the most life threatening of PWS’ major effects.2 The resulting obesity can lead to severe complications, including type 2 diabetes, heart disease, stroke, sleep disturbances, liver disease, and joint pain. Ironically, patients with PWS exhibit a lower than average muscle mass, and, therefore, need fewer calories than the average individual.3 Individuals with PWS require constant intervention to regulate their diet and activities. Counseling, behavior therapy, and support groups for patients with PWS, as well as their families are often recommended.

Individuals with PWS are prone to behavior problems, including hyperphagia; obsessive-compulsive behaviors, such as skin picking; stubbornness; temper tantrums; disobedience; stealing food or stealing money to buy food; social withdrawal; and anxiety.4

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

If an individual presents with clinical signs of PWS, genetic testing should be done to confirm the diagnosis, and family members should receive genetic counseling. There is no cure for PWS; however, early diagnosis and careful management can result in increased longevity and improved quality of life.2 From birth to adulthood, patients with PWS require medical intervention and meticulous supervision. Infants and young children necessitate special attention. At birth, the sucking reflex is weak and infants may not act hungry or show any interest in feeding. Physicians may recommend a naso-gastric feeding tube or special infant formulas and nipples due to hypotonia.5 Feeding problems and poor weight gain, often termed failure to thrive, are common in babies with PWS.

Rapid and excessive weight gain generally occurs between ages 1 and 6. Close monitoring of eating habits, weight gain, and other behaviors, such as hyperphagia, is critical during this developmental stage. Because fewer calories are needed in children with PWS, dietary restrictions are important to maintain appropriate weight. As patients with PWS develop, human growth hormone treatment may help stimulate growth and improve muscle tone. In addition, sex hormone replacement therapy may help children with PWS replace their low levels of hormones as they reach puberty.5 A healthy diet and frequent physical activity are encouraged to help maintain a normal weight, as well as locking cupboards and refrigerators to help patients avoid binge eating.2 Occupational, physical, and speech therapy may also be beneficial. Developmental therapy to improve social and interpersonal skills and mental health counseling might be suggested, as well.

Rapid and excessive weight gain generally occurs between ages 1 and 6. Close monitoring of eating habits, weight gain, and other behaviors, such as hyperphagia, is critical during this developmental stage. Because fewer calories are needed in children with PWS, dietary restrictions are important to maintain appropriate weight. As patients with PWS develop, human growth hormone treatment may help stimulate growth and improve muscle tone. In addition, sex hormone replacement therapy may help children with PWS replace their low levels of hormones as they reach puberty.5 A healthy diet and frequent physical activity are encouraged to help maintain a normal weight, as well as locking cupboards and refrigerators to help patients avoid binge eating.2 Occupational, physical, and speech therapy may also be beneficial. Developmental therapy to improve social and interpersonal skills and mental health counseling might be suggested, as well.

As patients with PWS move into adulthood, they will continue to need constant supervision. Patients with PWS never achieve the ability to control their own food intake. In many cases, adults with PWS live in group homes or residential care facilities that provide structure to support healthy eating, exercising, working, and socializing.

DENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

PWS can negatively impact oral health, including decreased salivary flow with thick, viscous saliva, enamel hypoplasia, high caries rates, and excessive tooth wear.6,7 A Norwegian study comparing the average salivary flow rate of patients with PWS to healthy patients found that individuals with PWS had much less salivary flow than controls.8 The low salivary flow and altered consistency of the saliva likely contribute to the high caries rate typically seen in this patient population. Other studies, however, have noted low caries rates among patients with PWS.6,8 This may be the result of intervention and education at an early age, the use of fluoride, and adoption of a low carbohydrate diet. One study found that the calcium and fluoride levels in the saliva of patients with PWS were notably higher than in the control group.6

Many patients with PWS take psychotropic drugs for depression, obsessive-compulsive behaviors, and mood swings. These medications can cause xerostomia.9 Patients/caregivers need to be educated about healthy nutrition, reducing sugar intake, and proper self-care. Dental hygienists should also provide product recommendations to help patients alleviate the symptoms of xerostomia.

Enamel hypoplasia is common among patients with PWS and, in combination with decreased salivary flow, creates a high-risk situation for the dentition. Unbalanced infant feeding is a possible cause of enamel hypoplasia.6 As more patients with PWS are diagnosed at birth, the risk of feeding and failure to thrive is reduced.6 Extensive tooth wear is another frequent manifestation of PWS, and may be caused by excessive erosion, attrition, abrasion, or a mixture of these conditions. One study suggested dental erosion may be associated with decreased salivary flow and the highly acidic diet sodas often consumed by patients with PWS on reduced carbohydrate diets.6 Another study noted that tooth wear, in the form of attrition and abrasion, was a serious problem for this patient population. The exact etiology of the tooth wear was difficult to determine because it has many possible causes.7 This same study also found an association between PWS, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and tooth erosion. Patients with PWS are commonly diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea and exhibit an increased body mass index. Both of these conditions are risk factors for GERD. No participants of this study reported symptoms of GERD, but some were medicated for severe reflux. In addition, patients with PWS generally have a high tolerance for pain, and symptoms of GERD may go unnoticed.

Periodontal disease is common among patients with PWS, but little information is available regarding this relationship. A case study done in Japan by Yanagita et al10 describes a 20-year-old Japanese man diagnosed with PWS at birth. The patient presented with severe crowding, anterior open bite, attrition of the first molars, generalized plaque, marginal redness, swelling, and food impaction. Localized areas of bone loss, mobility, and 4 mm to 8 mm pocketing were revealed upon further examination. The patient was diagnosed with localized periodontal disease and given oral hygiene instructions. As the patient became more familiar with dental treatment, a professional prophylaxis was also performed with an ultrasonic scaler. Root planing and periodontal surgery were contraindicated because of the patient’s poor oral hygiene. Yanagita et al suggested that the periodontal disease observed in this patient may be the result of poor oral hygiene, severe crowding, occlusal trauma, and positioning of the teeth—not necessarily a direct result of the genetic disorder. Nevertheless, the authors cite a 2010 report that revealed patients with PWS had an overactivation of the immune system and chronic low-grade inflammation.11 The study authors speculate that the compromised host immune response in patients with PWS may play a role in periodontal breakdown. Further studies are needed to shed light on the relationship between periodontal diseases and PWS.

Patients with PWS generally exhibit certain facial features, such as thin upper lips and small triangular mouths, that can complicate dental treatment (Figure 2).2 Micrognathia—especially of the mandible—hypodontia, and supernumerary teeth have been observed in patients with PWS.12 These conditions require that practitioners pay special attention to dental charting, treatment planning, and orthodontic issues. Patients with PWS have an unusually high pain tolerance due to hypothalamic dysfunction.1 The absence of normal response to pain stimulus could potentially interfere with the diagnosis of dental infection, disease, or injury. This condition emphasizes the need for dental team members to note any signs or symptoms of problems, including the identification of risk factors or slight changes in the oral condition, to prevent further damage to oral health.

BEHAVIORAL ISSUES

Patient behavior should be considered when treating PWS. Individuals with PWS tend to function best in highly structured environments with rules and limits in place to manage their behavior. Transitions and unanticipated changes can cause patients with PWS a great deal of stress. Employing some of the methods used to treat patients with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) may be helpful.9 For instance, providing a quiet, predictable environment can make treatment go more smoothly. Avoiding loud music, noisy dental equipment, and unnecessary chatter with caregivers or other dental team members can promote a calm atmosphere for the patient. Patients with PWS can be very sensitive to loud noise, touching, bright lights, and peculiar smells. Circumventing these distractions prior to treatment is ideal. Utilizing the “tell, show, do” approach to treatment can be very helpful.

Behavioral interventions are available for patients who may refuse treatment. The D-TERMINED Dental Program of Repetitive Tasking and Familiarization in Dentistry, used with patients with ASD, may provide dental team members with an option for effectively managing patients with PWS. The D-TERMINED program first involves a pretreatment assessment of the patient so the office can be prepared. Next, the patient will make many familiarization visits to the office so he or she can become comfortable with the office staff and environment before treatment is rendered. Finally, a dental team member helps the patient practice cooperation skills, which may include sitting in the dental chair correctly, making eye contact, listening to instructions, opening the mouth and keeping it open as instructed, and allowing instrumentation to be performed.13,14 The five “D” steps for learning cooperation skills include the following:13,14

- Divide the skill into smaller accomplishable parts. Take each step of a dental appointment and master it before moving onto the next step.

- Demonstrate the skill using the “tell, show, do” approach when introducing any new concept.

- “Drill the skill” by replicating the action until it becomes second nature.

- Delight the learner by using positive reinforcement to reward the patient when any small part of the appointment is conquered.

- Delegate the repetition by involving other dental team members in reinforcing skills and encouraging parents/caregivers to practice skills at home.

ORAL HYGIENE FACTORS

Thoughtful consideration also needs to be given regarding dexterity in patients with PWS. Gross motor skills are generally delayed 1 year to 2 years during childhood. Hypotonia usually improves with age; however, deficits in balance, strength, and coordination may linger.2 It is common for patients to undergo long-term physical and/or occupational therapy to promote strength and skill development.

Dental hygienists need to recommend the appropriate style of toothbrushes, floss, and other preventive aids according to patient symptoms. Wide-handle toothbrushes may make toothbrushing easier. Inserting the toothbrush into a bicycle handle grip or other device can be useful. Consulting an occupational therapist for additional information may be beneficial.

Patients with PWS often have strong visual-perceptual skills and may benefit from a pictorial display and written instructions vs spoken word alone.2,9 Dental hygienists must also emphasize to caregivers that patients with PWS should not have access to any dental products that could be consumed inappropriately, such as toothpastes or mouthrinses. While it is important to use flavorful toothpastes and rinses that patients find palatable, close supervision is necessary to prevent the patient from ingesting them.15

To best manage patients with PWS, dental professionals need to obtain a thorough medical/dental history from parents/caregivers regarding diagnosis, development, and any other medical concerns. Patients with PWS are generally treated by a team of health care professionals, which may include pediatricians, primary care physicians, endocrinologists, dietitians, physical and occupational therapists, speech-language pathologists, and psychologists. Appropriate members of this team should be contacted when necessary.

Caregivers should be encouraged to seek early intervention for patients with PWS. Ideally, patients should be seen when the first tooth erupts. Encouraging dental visits at a young age will enable the patient to become familiar with the environment and increases the likelihood of compliance. The importance of at least twice yearly visits for a thorough exam, prophylaxis, radiographs (if possible), and fluoride treatments should be emphasized to parents/caregivers.

A comprehensive treatment plan is indicated as the patient grows. This plan should include thorough self-care instructions, special oral hygiene aids, a fluoride regimen, sealants, occlusal appliances, and orthodontics, when indicated. Dietary guidelines should be addressed according to the patient’s medical and dental condition.

Patients with PWS?may have difficulty cooperating. Patients who are unable to complete a successful dental appointment in the traditional private-practice setting should be referred to a dental team that specializes in treating patients with special needs.

CONCLUSION

PWS can create many severe dental problems. Dental hygienists and other dental team members need to understand that treating patients with PWS may require a holistic approach to treatment planning and patient care. Due to the nature of PWS, the need for early intervention and education is imperative. Preventive measures, such as an oral exam when the first primary tooth erupts, self-care supervised by parents/caregivers, regular check-ups, and topical fluoride applications, should be the foundation of a comprehensive oral hygiene program. Dental hygienists can assist patients and caregivers in managing this condition through education and administering professional preventive care.

REFERENCES

- Yearwood EL, McCulloch MR, Tucker ML, Riley JB. Care of the patient With Prader-Willi syndrome. Medsurg Nurs. 2011;20:113–122.

- Prader-Willi Syndrome Association USA. Basic Facts about PWS. Available at: pwsausa.org/ syndrome/basicfac.htm. Accessed October 13, 2014.

- Mayo Clinic. Prader-Willi Syndrome. Available at mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/prader-willi-syndrome. Accessed October 13, 2014.

- Dykens E, Shah B. Psychiatric disorders in Prader-Willi syndrome: epidemiology and management. CNS Drugs. 2003;17:167–178.

- Prader-Willi Syndrome Association USA. Healthcare Guidelines for Individuals with Prader-Willi Syndrome. Available at: pwsausa.org/position/HCGuide/HCG.htm. Accessed October 13, 2014.

- Bailleul-Forestier I, Verhaeghe V, Fryns J, Vinckier F, Declerck D, Vogels A. The oro-dental phenotype in Prader-Willi syndrome: a survey of 15 patients. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2008;18:40–47.

- Saeves R, Espelid I, Storhaug K, Sandvik L, Nordgarden H. Severe tooth wear in Prader-Willi syndrome. A case-control study. BMC Oral Health. 2012;12:12.

- Saeves R, Nordgarden H, Storhaug K, Snadvik L, Espelid I. Salivary flow rate and oral findings in Prader-Willi syndrome: a case-control study. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2012;22:27–36.

- Dougall A, Fiske J. Access to special care dentistry, part 6. Special care dentistry services for young people. Br Dent J. 2008;205:235–249.

- Yanagita M, Hirano H, Kobashi M, et al. Periodontal disease in a patient with Prader-Willi syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:329.

- Viardot A, Sze L, Purtell L, et al. Prader-Willi syndrome is associated with activation of the innate immune system independently of central adiposity and insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:3392–3399.

- Atar M, Korperich E. Systemic disorders and their influence on the development of dental hard tissues: a literature review. J Dent. 2010;38:296–306.

- Wilkins EM. Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins; 2013.

- Tesini DA. The D-TERMINED Program of Repetitive Tasking and Familiarization in Dentistry: a Behavior Management Approach. Available at: nlmfoundation.org/media/clips/dental_medium_clip1.htm. Accessed October 13, 2014.

- Prader-Willi Syndrome Association USA. Dental Tips and Tricks. Available at: pwsausa.org/medical/Dentaltips&tricks.pdf. Accessed October 13, 2014.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November 2014;12(11):66–69.