Promote Oral Hygiene During Orthodontic Treatment

In order to prevent decalcification, caries, and gingivitis—common occurrences during appliance therapy—patients must improve their self-care regimens.

This course was published in the July 2014 issue and expires July 31, 2017. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Describe the prevalence of decalcification, caries, and gingivitis among adolescent orthodontic patients.

- Identify the critical oral hygiene issues faced by this patient population.

- Discuss strategies for improving oral hygiene among adolescent orthodontic patients.

The development of dental decalcification (Figure 1) or frank caries is a significant risk during the course of orthodontic treatment.1 Motivating young patients to maintain optimal oral health and hygiene practices, however, is a common challenge in orthodontics. The exhilaration of correcting a malocclusion can quickly be dampened by the presence of white spot lesions, dental caries, and gingivitis, which can progress to periodontitis. Orthodontic practitioners must live by the adage of “Do no harm,” being concerned first with patients’ overall oral health and second with the correction of malocclusions.

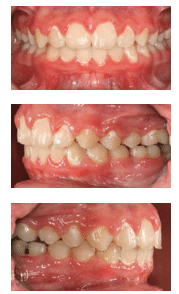

During the course of orthodontic treatment, decalcification, caries, and gingivitis occur in 2% to 96% of all patients—depending on which complication or combination of complications is evaluated.2 In a number of studies, decalcification and gingivitis (Figure 2A through Figure 2C). have been shown to present in as little as 1 month of bracket placement, while clinical dental decay can occur within the first 6 months of appliance placement.3

In the United States, orthodontic treatment is commonly accomplished with fixed appliances. Studies show that the introduction of fixed orthodontic appliances induces a rapid increase in the volume of dental plaque, which has a lower pH than the plaque found in nonorthodontic patients.4 There is also a rapid shift in the composition of the bacterial flora in plaque following the placement of appliances, with a significant increase in the levels of acidogenic bacteria, such as Streptococcus mutans and lactobacilli.5 Although some lesions resolve without intervention after appliance removal, most remain, causing esthetic concerns after treatment is completed.6,7

Gingivitis among children between the ages of 6 and 19 is estimated to range from 50% to 100%.8 Childhood gingivitis appears to reach a peak of approximately 80% among 11- to 13-year-olds, which also coincides with the age when traditional orthodontic treatment begins.9–11 The transition from gingivitis to periodontitis may also begin during the adolescent years.12–15

FACING CRITICAL ORAL HEALTH ISSUES

Some of the critical issues faced in orthodontic treatment among children age 6 to 19 are discussed below.

- Demineralization and gingival/periodontal issues are a direct result of the presence of orthodontic appliances and lack of proper oral hygiene during treatment. This association is well researched and documented.16–18

- Demineralization and gingivitis cause some of the most serious adverse effects experienced during orthodontic treatment, including hypomineralized enamel, dental caries, and periodontal diseases.19

- Encouraging patient cooperation to combat these problems with appropriate oral hygiene measures is one of the most challenging issues that dental health care providers face in the delivery of orthodontic treatment.20

Effective oral hygiene measures should include at least several of the following techniques and use of hygiene auxiliaries:

- Mechanical plaque removal—toothbrushing (manual or power); flossing, including the use of flossing aids and tools designed specifically for use with orthodontic appliances; oral irrigation; disclosing tablets for assistance in locating plaque; and regular prophylaxis

- Pharmacotherapeutic measures—fluoride therapy, including in-office topical application and prescription products for at-home use; fluoride dentifrices and mouthrinses; and chlorhexidine mouthrinse to decrease bacterial flora

- Mechanical protection of tooth surfaces—sealants and placement of glass ionomer cements under bands

- Diet—reduction in consumption of foods that cause acidity in the oral environment, (eg, fermentable carbohydrates) and increasing ingestion of cariostatic foods, such as dairy products

- Motivational communication—discussion of proper oral hygiene tactics before, during, and at the end of treatment, with an emphasis on oral health and esthetic benefits

MOTIVATING PATIENTS TO MAINTAIN ORAL HYGIENE

Motivating orthodontic patients to maintain optimal oral health remains challenging. The solution must be personalized for individual patients, who should be coached by their oral health professionals to incorporate adequate oral health behaviors into their daily lives. Oral hygiene regimens must be thorough enough to sufficiently control plaque and prevent formation of white spot lesions, decalcification, caries, and periodontal problems. Various strategies for such improvement are supported by scientific research, while others are based on clinician experience.

One of the consistent themes in the research is that patients should hear oral hygiene discussions early and hear them often. Marini et al21 investigated the effects of motivation and oral hygiene instruction provided by dental hygienists and the type of toothbrush used. The study included four groups of 15 participants each. Group one and group two received oral hygiene instructions from a dental hygienist at the initiation of treatment and at weeks 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20. Group one used power toothbrushes and group two used manual toothbrushes. Group three used power toothbrushes and group 4 used manual toothbrushes, but members of these groups did not receive any oral hygiene instruction. The groups with the lowest plaque index scores were those that received the oral hygiene instruction, regardless of which type of toothbrush was used.

Silva et al22 also demonstrated a significant improvement in oral hygiene levels among orthodontic patients who received periodic instruction and evaluation of oral hygiene levels during the course of orthodontic treatment, compared to patients who only received oral hygiene instructions at the initiation of treatment. Ongoing research validates the need for repetitious instructions provided by oral health professionals to improve oral health outcomes among orthodontic patients.

Research has also investigated whether the source of oral hygiene instruction has an effect on the outcome of oral hygiene levels during active orthodontic treatment. Lees et al23 compared oral hygiene instructions delivered verbally vs written vs videotape among 65 orthodontic patients. The study showed no significant difference in the effectiveness of delivery methods in correlation to the incidence of decalcification and gingivitis.23

In a study of 150 orthodontic patients who were given oral hygiene instruction by a clinician, a comparison was made of verbal information only; verbal instruction with a model demonstration; verbal information with demonstration on a model and self-application by the patient with clinician supervision; verbal information using two-dimensional illustrations; and verbal information using illustrations and self-application with clinician supervision. The two groups that showed the best oral hygiene during treatment were those that received oral hygiene information with either illustrations or models under the supervision of clinicians.24

The use of motivation in oral hygiene instruction has also demonstrated positive results in improving oral hygiene during treatment. In a study of 62 adolescent patients undergoing orthodontic treatment, three different motivational techniques were compared. One group of patients received traditional chairside motivational instruction with plaque disclosure, a discussion of plaque and its effects on oral health, and toothbrushing techniques. The second group had pH tests conducted on their saliva samples, a discussion of microorganisms and acid demineralization, and demonstration of toothbrushing techniques. The third group examined their bacterial flora under a phase contrast microscope, had plaque disclosure done chairside, and were instructed on toothbrushing techniques. Researchers concluded that the group that used the phase contrast microscopy and received the conventional method of plaque disclosure and demonstration of the horizontal scrubbing method of brushing had the greatest impact on patients, positively influencing their oral hygiene status.25

A review of these studies yields a common theme—oral hygiene instructions provided by dental hygienists (at the onset of and during treatment) and the use of adjunctive educational devices (eg, models, illustrations, and even phase contrast microscopy) may be helpful in keeping patients motivated to maintain oral hygiene during the course of orthodontic treatment.

PRACTICAL APPROACHES TO IMPROVING HYGIENE

Many methods are available to encourage orthodontic patients to improve their oral hygiene and oral health outcomes. Before patients are prompted to change their habits, however, oral health professionals must initiate change within the practice setting by altering their view of oral hygiene treatment. In a busy orthodontic practice, it is not uncommon to schedule 15-minute appointments for an archwire check or change. This schedule leaves little room for discussion or oral hygiene instruction. With only small segments of time scheduled for patient-provider interaction, many practitioners rely solely on their assistants to engage in meaningful conversations with patients about oral hygiene problems. The orthodontist can support the significance of these conversations by discussing the importance of oral hygiene and identifying the negative effects of neglecting daily self-care with patients.

Scheduling longer intervals between visits—in part due to the efficiency of self-ligating brackets—is becoming more common. This inhibits the ability to provide consistent oral hygiene instruction. Intervals ranging from 8 weeks to 12 weeks between archwire changes are not uncommon. This is economically advantageous for the orthodontic practice because treatment requires fewer visits and on the surface appears to be convenient for patients. In many cases, this practice is ill advised—especially when hygiene and other orthodontic compliance issues are of note. It is difficult to monitor hygiene and reinforce hygiene instruction if patients are seen only five times or six times per year. Rather, it is advised that some visits be less focused on orthodontics and center more on ensuring oral hygiene is being properly maintained. There is a need for more scientific research on the relationship between increased treatment visit intervals and treatment outcomes related to oral hygiene.

Clinicians must also consider the psychological development of orthodontic patients. Erickson26 reports that adolescent orthodontic patients typically fall into one of these two groups: industry vs inferiority (age 7 to 11) and identity vs role confusion (age 12 to 17). In the younger group, children are more interested in competition and may value a reward system—which makes contests highly appropriate. The downside to oral hygiene contests is the feeling of inferiority should they not experience success in achieving the “prize.” Specific instructions on how to achieve proper hygiene levels that are not overwhelming are appropriate for this group. Parental influence is decreasing and peer group influence is increasing. Showing images of patients in their age group (with identities masked) who display good oral hygiene vs poor oral hygiene could be an effective motivational tool among this patient population.

The older group is experiencing some of the biggest changes in regard to personal identification, somatic and sexual changes to their bodies and behaviors, and a diminished role of parents in decision making. They often have a sense of omnipotence and “bad things don’t happen to me.” Orthodontics—and subsequently oral hygiene—may be of low importance. Helping this age group understand that good oral hygiene during treatment will have a lasting impact on “looking good” for the rest of their lives can be a motivator. One strategy might be working with the patient primarily and demonstrating trust in him or her as a “young, responsible adult,” thereby placing less responsibility on the parent to enforce oral hygiene standards.

Another technique to improve oral hygiene during orthodontic treatment is to document poor oral hygiene with photographs—which may then be used as a teaching aid for both patients and parents. This strategy is useful in educating patients on the importance of oral hygiene and it provides some type of legal defense should litigation arise over the compromised oral health resulting from poor hygiene during treatment.

Building a team outside of the orthodontic practice to emphasize the need for good oral hygiene during treatment is another powerful technique. The school environment is an excellent place to begin. Orthodontic practice members can provide seminars to faculty, school nurses, and students on the importance of oral hygiene and the ill effects if it is not maintained during treatment. Orthodontic team members can provide patients with formal letters for teachers and school administrators that explain the need for students to brush following lunch. If patients partake in a summer camp, the leadership should be made aware of the importance of campers maintaining their oral hygiene.

An excellent system of communication between the general dentist, pediatric dentist, and dental hygienist is crucial to reinforcing oral hygiene. The communication should be between the professionals involved and not dependent on the patient and parent to serve as the conduit for the exchange of information. If there is some type of motivational contest at the orthodontic practice for good oral hygiene, the dentist and dental hygienist should also be included as “judges” for evaluating hygiene and may report findings to the orthodontic practice.

TOOLS OF THE TRADE

Ensuring that patients use the appropriate hygiene accessories to maintain their oral health during treatment is not easy. Some offices give patients either a power toothbrush or an oral irrigating device at the onset of treatment. The practitioner must make the decision as to whether this is economically feasible. Some practices make the adjuncts available for purchase at the office. The retail sale of these tools, however, can create additional accounting requirements, including collecting and reporting sales tax on these items. It may behoove orthodontic practices to provide a meaningful discount coupon for purchase of the recommended items at the onset of treatment and inquire at the next visit as to whether the adjunct was purchased and in use.

While research shows that power toothbrushes are highly effective in plaque removal,27 manual toothbrushes—when used with the correct technique, frequency, and duration—can be equally effective.28 Providing 2-minute timers for patients who prefer manual toothbrushes may encourage them to brush for the recommended amount of time.

Less expensive oral hygiene aids, such as toothbrushes, floss, floss threaders, and other flossing aids designed for use during orthodontic treatment, should be dispensed during every orthodontic visit. Flossers and floss tools that feature age-appropriate designs and colors/characters may improve compliance.

An additional strategy is to have the practice purchase prescription-strength fluoride toothpaste and dispense it free-of-charge to patients who are in danger of significant decalcification. It is a minimal expense that can boost clinicians’ confidence that they have done all they can to assist the patient and family in reducing decalcification and caries risk.

Oral irrigating devices elicit the greatest response from child and adolescent orthodontic patients.29,30 The novelty of a “squirt gun” type of irrigating appliance appeals to these patients. Due to the “cool factor,” patients may be more cooperative in utilizing these devices. Sharma et al31 also found that oral irrigators were more effective at cleaning—not only interproximally but also around the brackets vs manual brushing and flossing, regardless of the flossing aid utilized. The downside to irrigating devices is the high cost (typically $100), which may prove problematic for some families.

CONCLUSION

The impact of poor oral hygiene during orthodontic treatment can have long-lasting effects on oral health and smile esthetics. Significant decalcification and periodontal problems arising from treatment generally do not go away. There is no perfect strategy in place to combat these ill effects. Practitioners have to develop, implement, and periodically evaluate the efficacy of their strategies for keeping this “collateral damage” of orthodontic treatment to a minimum.

REFERENCES

- Derks A, Katsaros C, Frencken JE, van’t Hof MA, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM. Caries-inhibiting effect of preventive measures during orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. A systematic review. Caries Res. 2004;38:413–420.

- Gontijo L, Cruz Rde A, Brandao PR. Dental enamel around fixed orthodontic appliances after fluoride varnish application. Braz Dent J. 2007;18:49–53.

- Ogaard B. White spot lesions during orthodontic treatment: mechanisms and fluoride preventive aspects. Seminars in Orthodontics. 2008;14(3):183–193.

- Chatterjee R, Kleinberg I. Effect of orthodontic band placement on the chemical composition of human incisor tooth plaque. Arch Oral Biol. 2008;24:97–100.

- Lundstrom F, Krasse B. Streptococcus mutans and lactobacilli frequency in orthodontic patients; the effect of chlorhexidine treatments. Eur J Orthod. 1987;9:109–116.

- Artun J, Thulstrup A. A 3-year clinical and SEM study of surface changes of carious enamel lesions after inactivation. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989;95:327–333.

- Kock G, Linde J. The effect of supervised oral hygiene on the gingiva of children. The effect of tooth brushing. Odontol Revy. 1965;16:327–335.

- Bjorby A, Loe H. Gingivala och munhugieniska forhallender has skolbarn. Goteborg, STFT. 1969;61:561–572.

- Marshal-Day CD, Stephens RG, Quigley LF. Periodontal disease: prevalence and incidence. J Periodontol. 1955;26:185-203.

- Powell RN, Alexander AG. The treatment of periodontal disease. 12. Periodontal disease in childhood. Br Dent J. 1966;120:351–353.

- Wade AB. An epidemiological study of periodontal disease in British and Draqi children. Parodontopathies (Geneva). 1966;18:19.

- Ramfjord S, Emslie, R et al. Epidemiological studies of periodontal diseases. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1968;58:1713–1722.

- Stallard RE. Current concepts in periodontal disease. J Dent Child. 1967;34:204–210.

- Parfitt GJ. Periodontal diseases in children. In Finn SB, ed. Clinical Pedodontics. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co; 1963.

- Baer PN, Benjamin SD. Periodontal Disease in Children and Adolescents. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Co;1974.

- Lovrov S, Hertrich K, Hirschfelder U. Enamel demineralization during fixed orthodontic treatment—incidence and correlation to various oral-hygiene parameters. J Orofac Orthop. 2007;68:353–363.

- Travess H, Roberts-Harry D, Sandy J. Orthodontics. Part 6: Risks in orthodontic treatment. Br Dent J. 2004 Jan;196:71–77.

- Kukleva MP, Shetkova DG, Beev VH. Comparative age study of the risk of demineralization during orthodontic treatment with brackets. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 2002;44:56–59.

- Chang HS, Walsh LJ, Freer TJ. Enamel demineralization during orthodontic treatment. Aetiology and prevention. Aust Dent J. 1997;42:322–327.

- Hamdan AM, Maxfield BJ, Tüfekçi E, Shroff B, Lindauer SJ. Preventing and treating white-spot lesions associated with orthodontic treatment: a survey of general dentists and orthodontists. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012;143:777–783.

- Marini I, Bortolotti F, Parenti SI, Garro MR, Bonetti GA. Combined effects of repeated oral hygiene motivation and type of toothbrush on orthodontic patients: A blind randomized clinical trial. Angle Orthod. 2014 March 18. Epub ahead of print.

- Silva FOG, Correa AM, Terada HH, Nary Filho H, Caetano MK. Programa surevisionado de motivacae e intstro de hygiene e sioterapia buccal em crian as com aparelhos orthodonticos. Rev Odontol Univ Sao Paulo. 1990;4(1):11–19.

- Lees A, Rock WP. A comparison between written, verbal, and videotape oral hygiene instruction for patients with fixed appliances. J Orthod. 2000;27:323–328.

- Ay ZY, Sayin MO, Ozat Y, Goster T, Atilla AO, Bozkurt FY. Appropriate oral hygiene motivation method for patients with fixed appliances. Angle Orthod. 2007;77:1085–1089.

- Acharya S, Goyal A, Utreja AK, Mohanty U. Effect of three different motivational techniques on oral hygiene and gingival health of patients undergoing multibracketed orthodontics. Angle Orthod. 2011;81:884–888.

- Erickson EH. Childhood and Society. New York: Norton; 1950.

- Yaacob M, Worthington HV, Deacon SA, et al. Powered versus manual toothbrushing for oral health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Jun 17;6:CD002281. Epub ahead of print.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on infant oral health care. Pediatr Dent. 2013;35(Suppl):137–141.

- Husseini A, Slot DE, Van der Weijden GA. The efficacy of oral irrigation in addition to a toothbrush on plaque and the clinical parameters of clinical periodontal inflammation: a systtematic review. Int J Dent Hyg. 2008;6:304–314.

- Warren PR, Chater BV. An overview of established interdental cleaning methods. J Clin Dent. 1996;7:65–69.

- Sharma NC, Lyle DM, Qaqish JG, Galustians J, Schuller R. Effect of a dental water jet with orthodontic tip on plaque and bleeding in adolescent patients with fixed orthodontic appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133:565–571.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. July 2014;12(7):67–71.