Oral Pathology of Tots and Teens

The identification, etiology, and treatment of common oral lesions in infants, children, and adolescents.

This course was published in the February 2010 issue and expires February 2013. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Review the soft tissue lesions often found in pediatric patients

- Discuss the etiologies and treatment modalities for pediatric soft tissue lesions.

- Understand the potential that laser dentistry offers the treatment of this patient population.

Many common oral lesions are seen in infant, toddler, and adolescent patients that are easily identified. Mouth ulcers are more frequently seen in young children, most often due to viral infection, such as herpes gingivostomatitis or hand, foot, and mouth disease. Recurrent ulcers are more commonly seen in older children and are typically caused by canker sores or aphthous stomatitis. The side effects of chemotherapy, radiation, and certain medications can also cause oral lesions in pediatric patients. Different foods and the ingredients in toothpastes and mouthrinses are known triggers of oral lesions. When the etiology of an oral lesion is not known, a record of what the child has eaten and been exposed to should be kept in order to determine the most likely cause.

COMMON SOFT TISSUE LESIONS

Dental professionals, with their knowledge of the size, shape, color, and texture of normal oral structures, should be able to identify the following types of lesions and manage their treatment.

Aphthous ulcers. These ulcers affect the nonkeratinized mucosa and present with a yellowish-white base surrounded by an erythematous halo. They usually heal within 10 days to 14 days without evidence of scarring. Patients generally present with one to three lesions. Precipitating factors include stress, trauma, and certain foods.1 Tetracycline suspension is often used for treatment. Aphthous ulcers may be associated with certain diseases such as Crohn’s disease, Reiter syndrome, Behcet’s syndrome, lupus, celiac sprue, and ulcerative colitis. In children, celiac and Crohn’s disease are especially important to diagnose early because diet may be a crucial part of the occurrence. Lauryl sulfate, an ingredient in many toothpastes, may precipitate the onset of these lesions as well (Figure 1).

Bohn’s nodules. These are smooth whitish cysts or fibrous nodules that are sometimes found in the mouths of newborns. They are located at the junction of the hard and soft palate and along lingual and buccal parts of the dental ridges, away from the midline. These nodules are 1 mm to 3 mm in size, and filled with keratin. They undergo spontaneous resolution within a few months after birth.

Candidiasis. Bright red shiny areas are evidence of acute atrophic candidiasis, and the smaller whitish plaques are typical of acute pseudo-membranous lesions (thrush). White plaques may occur anywhere in the mouth and can easily be stripped (wiped) off of the mucosa.

Congenital epulis. This benign lesion appears at birth as a pedunculated firm mass attached to the gingival mucosa of the anterior alveolar ridge. It should be excised. Recurrence is uncommon.

Epstein’s pearls. Inclusion cysts that appear as small white-yellow nodules on the palatal midline, they disappear spontaneously in a few months.1

Eruption hematoma or eruption cyst. These are bluish lesions on the labial or occlusal aspect of the gingival tissue over the site of an erupting primary or permanent tooth. Treatment is not required (Figure 2).

Fibroma. This is a smooth surface, well-circumscribed, elevated nodule that is normal in color. It is usually firm and may occur anywhere on the oral mucosa but most commonly appears on the buccal mucosa, lips, tongue, and palate. Excision is the preferred treatment and recurrence is rare (Figure 3).1

|

|

|

Acute herpetic gingivostomatitis. Caused by the herpes simplex I virus, these lesions are characterized by extreme gingival redness and swelling. Multiple superficial ulcers that have a bright red halo on the mucosa are also common. This condition should be treated symptomatically and often lasts 7 days to 10 days and is self-limiting. It is commonly associated with lethargy and a febrile condition in young children (Figure 4).

Recurrent herpes labialis. Herpes simplex I is the etiology of this red lesion, which is often surrounded by a white halo. This fluid filled vesicle(s) is often accompanied by pain, elevated body temperature, and generalized malaise.

Chronic dentoalveolar abscess (parulis). This is a localized swelling of the attached gingiva on the buccal or lingual of an abscessed primary or permanent nonvital tooth (Figure 5).

Localized aggressive periodontitis. This condition usually occurs with adolescents rather than young children. Gross destruction of the alveolar bone around the teeth is a characteristic finding.

Cheekbite (self-inflicted). A bite can be treated symptomatically with topical anesthetic gels. The practitioner should determine if this is a chronic condition or acute. Also, the patient should be made aware that he or she is chewing on the lip and/or cheek (Figure 6).

|

|

|

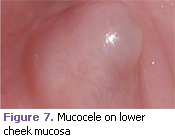

Mucocele. This is also called a mucous extravasation or retention cyst. History of lip trauma is frequently the etiology (Figure 7).

Oral squamous papilloma. This presents as a pedunculated lesion with finger-like processes. In children, sexual abuse should be considered a possible etiology.2

Migratory glossitis (geographic tongue). Multiple areas of denuded filiform papillae cause depapillated areas of atrophy. These reddened areas are usually irregular and surrounded by a thin keratotic white zone. Patients may complain of loss of taste sensation or a burning sensation, especially when eating citrus fruit or drinks and/or eating spicy foods. This condition may also be associated with Reiter’s syndrome.1

Gingival hyperplasia. This condition is a multinodular diffuse overgrowth of the gingival fibrous tissue with normal color. It is often associated with multiple syndromes and disorders. It may be hereditary or caused by various medications; anti-transplant and anti-seizure medications are the most common etiologies (Figure 8).1

Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (previously called Trench Mouth/Vincent’s Disease). Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis is an infectious disease of acute onset characterized by ulceration and necrosis predominately of the gingival papilla. Etiology is usually fusospirochetal. Pre dis posing factors include: smoking, poor oral hy – giene, and anxiety. It is usually found in adolescents and young adults. Clinically, there is destruction and necrosis of the interdental papillae. Pain, malodor, and febrile conditions are common. Treatment includes rinsing with warm water and 3% hydrogen peroxide following a gentle prophylaxis. Antibiotic therapy is sometimes indicated (Figure 9).1

|

|

|

Herpangina. This viral disease is caused by the coxsackie virus (specifically A-16) and is manifested by small, multiple vesicular lesions involving the uvula, the tonsillar fauces, and soft palate. The vesicles rupture leaving small punctuate ulcerations surrounded by reddish borders. Dysphagia, malaise, and fever may be present. Resolution occurs within 7 days to 14 days, and no treatment is indicated. Adequate hydration should be recommended.1

Lipoma. This lesion is a well-circumscribed, submucosal mass that is soft and freely movable. It has a slight yellowish color due to adipose cells. The buccal mucosa is the most common site of occurrence.2

Ranula. A ranula is a unilateral bluish translucent lesion that occurs on the floor of the mouth. This mucous extravasation phenomenon or mucous retention cyst (mucocele) should be excised (Figure 10).

Pyogenic granuloma. This lesion usually appears as a sessile, erythematous nodule most commonly on the gingiva. It is usually less than 1 cm in diameter and soft on palpation. In pregnant women, this is commonly referred to as pregnancy tumor gingivitis (Figure 11).1

|

|

USING LASERS IN THE TREATMENT OF COMMON ORAL LESIONS

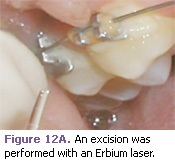

The use of Erbium lasers can be very effective in the treatment of oral lesions in pediatric patients. They have been proven safe and effective for the removal of tooth decay, cavity preparation, and many soft tissue and hard tissue surgical procedures.3,4 The Food and Drug Administration approved the Erbium laser for use in the United States in 1997.

An Erbium laser searches for the water that is found in enamel, dentin, and carious dentin, in addition to the water in soft tissue. The laser then explodes (ablates) the molecules of enamel, dentin, and carious dentin in the path of the invisible laser beam. This micro-explosion is not seen, felt, or heard by the patient. In soft tissue, the laser vaporizes the molecules of water within the tissue.

When laser therapy is used, surgery can often be performed without anesthesia because the Erbium laser, which is the only type of laser used for cavity preparations, is able to block the sensory innervation from the tooth to the brain. The dental laser often eliminates the unpleasant after-effects associated with many dental procedures, such as soreness, bleeding, inflammation, sutures, and numbness, because of the minimal depth of penetration of the Erbium laser versus a scalpel. Therefore, faster healing occurs. It also creates no known side effects. Other advantages of laser surgery include the minimization of intra-operative hemorrhage and a decrease in post-operative pain, which are due to the coagulating effect of the laser and the minimal depth of penetration of the tissue.5 Table 1 provides a list of the advantages of using laser therapy in pediatric dentistry.6-8

|

|

|

CASE STUDIES

The following cases demonstrate the use of the Erbium laser in the treatment of a variety of soft tissue lesions in pediatric patients. In this case, a 12-year-old patient presented with a fibroma most likely caused by her orthodontic brackets irritating the mucosa (Figure 3). The laser excision was performed with only a topical anesthetic (Figures 12A-12C).

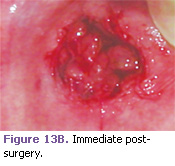

This 7-year-old boy presented with a mucocele that was located on the labial mucosa of the lower lip (Figure 7). This lesion was removed with an Erbium laser with the use of local anesthetic. One absorbable suture was placed for hemostasis (Figures 13A-13C).

|

|

|

REFERENCES

- Budnick SD. Handbook of Pediatric Oral Pathology. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers Inc; 1981:39,97,131- 133,209,119,210,225.

- Rapp R, Winter GB. Color Atlas of Clinical Conditions in Pedodontics. London: Wolfe Medical Publications Ltd; 1979:78-121.

- Kotlow L. Lasers and pediatric dental care. Gen Dent. 2008;56:618-627.

- Olivi G, Genovese MD, Caprioglio C. Evidence-based dentistry on laser paediatric dentistry: review and outlook. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2009;10:29-40.

- Margolis FS. The erbium laser: the Star Wars of dentistry. Private Dentistry. 2009;14(5):14-22.

- Margolis FS, Olivi G. Lasers in Lasers in Pediatric Dentistry: A Practical User’s Guide and Atlas. Chicago: Quintessence; 2010. In press.

- Bello-Silva MS, de Freitas PM, Aranha AC, Lage-Marques JL, Simões A, de Paula Eduardo C. Low- and high-intensity lasers in the treatment of herpes simplex virus 1 infection. Photomed Laser Surg. 2009 Aug 27:Epub.

- Burns AJ, Navarro JA. Role of laser therapy in pediatric patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(1 Suppl):82e-92e.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. February 2010; 8(2): 58-61.