Autism and the Dental Operatory

Successfully treating patients who have autism spectrum disorders.

This course was published in the February 2010 issue and expires February 2013. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Recognize the behaviors of autism.

- Evaluate the cognitive and emotional abilities of patients who have autism.

- Analyze oral health needs of patients who have autism.

- Formulate dental management ideas for patients who have autism.

When first told that their children have autism, many parents experience a wave of disbelief that sometimes overshadows other feelings. This is often followed by vigorous research into the disorder by checking every website, placing phone calls, and signing up for classes about autism. They want to cure their child as quickly as possible. However, parents often find that the process of accepting, understanding, and helping the child with autism is not a sprint but rather a marathon.

WHAT IS AUTISM?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines autism as one of a group of disorders known as autism spectrum disorders (ASDs). ASDs are developmental disabilities that cause substantial impairments in social interaction and communication, and include the presence of unusual behaviors and interests. Many people who have ASDs also have unusual ways of learning, paying attention, and reacting to different sensations. The thinking and learning abilities of people who have ASDs can vary from gifted to severely challenged. ASDs begin before the age of 3 years and continue throughout a person’s life.1 ASDs include autistic disorder, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (including atypical autism), and Asperger syndrome. These conditions all have some of the same symptoms, but they differ in terms of when the symptoms start, how severe they are, and the exact nature of the symptoms. The three conditions, along with Rett syndrome and childhood disintegrative disorder, make up the broad diagnosis category of pervasive developmental disorders.2

WHAT CAUSES AUTISM?

Autism is a disorder in which the various parts of the brain have difficulty working together to accomplish complex tasks.2 Scientists agree that both genetics and environment play a role. Researchers have identified a number of genes associated with the disorder and have found irregularities in several regions of the brain, especially the limbic system and cerebellum. These abnormalities suggest autism may result from the disruption of normal brain growth and the interruption of communicating neurons.3 Imaging studies of people who have autism during the first 2 years of life show an abnormal overgrowth of the brain with selective elimination (pruning) of synapses and axonal process, which impair the neural systems.4-7 People who have autism have abnormal structure and or function of the limbic system (amygdala, cingulate gyrus, and hippocampus).8

While controversy continues to exist surrounding the relationship between vaccines and autism, research shows no correlation.4,9-11 The National Institutes of Health states: “To date there is no definite, scientific proof that any vaccine or combination of vaccines can cause autism.”12

Fragile X syndrome, mental retardation, tuberous sclerosis, and seizure disorders are all associated with the diagnosis of autism.13-15 Autism runs in families and is often associated with abnormalities on chromosomes 2, 7, 15, 16, and 19.4 Studies conducted on families have helped researchers understand how genes contribute to autism. Studies show that between identical twins, if one child has autism, then the other will be affected approximately 75% of the time.10,11 In fraternal twins, if one child has autism, then the other is affected approximately 3% of the time.10,11 Also, parents who have a child with an ASD have a 2% to 8% chance of having a second child who is also affected.10,11 In families with a child who has an ASD, other family members often exhibit autism-like symptoms such as obsessive compulsive tendencies, impulsiveness, irritability, and anxiety disorders.4

CHARACTERISTICS

Children who have autism do not participate in group play but rather appear to be in their own world with the inability to share in another child’s interest in an activity. These young children do not seem to recognize that other people have intentions, desires, feelings, and beliefs, and that these thoughts may differ from their own (theory of mind). This leads to the inability to interpret or predict the behavior of others as well as the failure to use body language to interact with others (social conflict).4 Functional MRIs show that many people who have autism also lack the ability to activate areas in the cerebellum traditionally associated with motor integration.4 They often have difficulty in areas of balance, movement, memory, and visual perception skills.

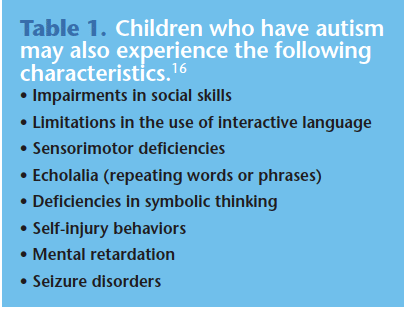

People who have autism experience difficulty with complex tasks that require coordination among brain regions working together. Abnormalities in brain circuitry provide the most likely explanation for why children who have autism have difficulty with complex tasks that require coordination among brain regions but do well with tasks that require only one region at a time.1 See Table 1 for a list of other characteristics sometimes seen in children who have autism.16

Cognitive impairment occurs in approximately 70% of people who are diagnosed with autism and 40% exhibit severe cognitive impairment.4 The majority of people who have autism function in the moderate range of mental retardation.4

WHO IS AFFECTED?

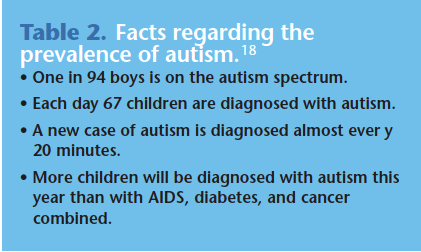

ASDs occur in all racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups and are four times more likely to occur in boys than in girls.1 In 2007 the CDC’s Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network released data in 2007 that showed approximately one in 150 8-year-old children in multiple areas of the United States has an ASD.17 The high rate of prevalence is most likely due to improved diagnosis and the widening of the definition to include spectrum disorders that may cause milder symptoms. See Table 2 for more facts on the prevalence of autism.18

CAPABILITIES

Approximately 15% of people who have autism can achieve reasonable self-sufficiency, attain a high school education, retain employment, and live on their own; 15% to 20% are able to function well with periodic family or governmental support.4 These two groups consist mainly of people with intelligent quotients in the below-normal range (79).4 The remaining 65% are usually profoundly dependent on others throughout their lives. About 30% of this population live with their families and the other 35% reside in group homes.4

FACTS AND RESEARCH

Autism is the fastest-growing serious developmental disability in the United States and costs the nation more than $90 billion per year, a figure expected to double in the next decade.18 Autism receives less than 5% of the research funding of many less prevalent childhood diseases.18 On the positive side, the CDC’s Centers for Autism and Developmental Disabilities Research and Epidemiology are working on a large, population-based study to better understand the possible risk factors for and causes of autism. Called the Study to Explore Early Development, this project will help answer the many questions needed to find the causes of autism and, if possible, develop strategies to prevent this complex disorder.18

ORAL HEALTH STATUS AND DENTAL NEEDS

Each child diagnosed with autism is unique and there is no mold that children with autism automatically fall into. Many attempts and various techniques are necessary to teach a child with autism. What works for one child will not necessarily work for another. With the right therapies, children who have autism can make friends, have conversations and play dates, and be mainstreamed into traditional school systems. Many can become good dental patients and be successfully treated in a dental office.19

The rate of caries and periodontitis among children who have autism is comparable to those in the general population.20 If the caries rate is increased, it is often due to a preference for soft and sweet food or the pouching of food in the buccal mucosa.20

Young children with autism may exhibit behaviors such as impulsivity, agitation, anger, aggressiveness, and self-injury. Adolescents may develop psychiatric illness including anxiety disorders, mood disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, and schizophrenia.4 Many of the medications used to treat these behaviors and illnesses cause systemic side effects. For example, antipsychotic agents can induce motor disturbances, which affect speech and swallowing, and selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors may cause diarrhea, nausea, or dizziness.4 Both of these medications can cause xerostomia. Central nervous system medications, such as methylphenidate, may promote anorexia and decreased weight gain in children as well as insomnia.4 Eruption patterns might be delayed due to medications such as phenytoin, which can induce gingival hyperplasia.21

Other oral concerns of children who have ASD include a prevalence of bruxism and a reduced threshold of pain.20 Children who have autism might display damaging oral habits, such as tongue thrusting, and selfinjurious behavior, such as picking at the gingiva or biting the lips.21 Children who have autism sometimes have difficulty with balance and movement so dental professionals might see an increase in trauma to both the primary and the permanent dentition.12

PROVIDING DENTAL TREATMENT

Dental professionals will treat children who have autism at greater rates than in the past due to the increased numbers of identified cases. They need to be familiar with behavioral traits of children who have autism and consider what any child experiences when visiting a dental office. Children must voluntarily enter the operatory, position themselves in the dental chair, sit back while the dental chair goes up, keep the body positioned consistently in the dental chair with legs out straight and hands at the side or on the abdomen, and make eye contact with the dental professional as instructions are given. They also need to open their mouths and keep them open consistently, allowing dental instruments to be placed in the mouth and taken out of the mouth repetitively as required by the procedure; ask for breaks in a safe manner; respond appropriately to instructions; and sit still in the chair as it is lowered for patient release.19 All of these can be difficult for any child but for a child who has autism and lives daily by sameness and continuity, these are monumental tasks.

Dental professionals must talk with and listen to caregivers prior to the first appointment to determine the communication skills needed to effectively interact with the patient.21 Soliciting suggestions from caregivers about behavior management techniques that work best for their child is helpful. Often children who have autism are hyperactive and easily frustrated so the best approach is to desensitize the appointment by letting the patient become familiar with the office, staff, and equipment.

Caregivers should be trained to practice the skills necessary for a successful dental appointment at home.21 A parent might have the child sit in a recliner with hands on his or her abdomen. The parent could use a toothbrush or plastic mouth mirror in the child’s mouth. As the child repeats the motions used in dentistry, he or she will become more accepting of the dental visit. Subsequent appointments should be scheduled on the same day of the week in the same operatory with the same personnel.21

The key for dental professionals is to go slowly and accomplish each step before moving to the next one. The appointments should be short and positive. Instruments should be kept out of sight, lights should be low, and noise should be minimized because children who have autism often exhibit tactile and auditory hypersensitivity and may have exaggerated reactions to light, sound, and smells.16

Eye contact needs to be established with the child. If the dental professional can get the patient to respond to a request to “look at me,” it is a good indication that the clinician will be successful. It forces the patient to pay attention, and it helps to establish a relationship between the dental professional and the patient.19

Children who have autism take everything literally so words must be selected carefully and words or phrases with double meanings should be avoided. If the practitioner says, “This will be a piece of cake,”the child will be looking for the cake. The dental professional should use a quiet, nonthreatening voice, and avoid getting into the child’s space. A “tell-show-do” approach to providing care should be used.19,21 This means describing the procedure before it occurs, showing the instruments that will be used, and then doing it. Children who have autism like routines so a repetitive series of interactions should be used. Dental professionals should try to make interactions easy and successful so the child feels competent. Then more complexity can be added to future dental appointments to help shape behavior and flexibility. Just because a child who has autism conquers a skill at one appointment does not mean he or she will remember it again; repetition is the key at every appointment.21

Since children with autism are often visual learners, picture boards may be helpful to depict the dental appointment.19 Velcro pictures showing emotions such as happy or sad, holding up an arm if the child needs a break, and hands on the abdomen might help during the appointment. Pictures of a dental chair, the dental light, “the tooth counter,” and a child in the chair with the professional counting the teeth could be used by parents or dental health professionals to help communicate appointment procedures. Social stories are also available online or can be created by the dental office to help the child who has autism cope with the dental appointment.22-24

David Tesini, DMD, MS, a pediatric dentist who works with children who have autism advises, “Let’s take the challenge of working with individuals with ASDs as an opportunity to challenge our own abilities. Patients who present with special needs are not ‘problems’ but rather they offer us a challenge as professionals to better meet the needs of a ‘specific individual.'” 19

REFERENCES

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Autism Spectrum Disorders. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism. Accessed January 11, 2010.

- Boyles S. Autism affects child’s entire brain. Available at: www.webmd.com/brain/Autism/news/20060816/autism-affects-childs-entire-brain. Accessed January 11, 2010.

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Strokes. Autism Fact Sheet. Available at: www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/autism/detail_autism.htm. Accessed January 11, 2010.

- Friedlander A, Yagiela J, Paterno V. The neuro – pathology, medical management and dental implications of autism. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006; 137:1517-1527.

- Lainhart J. Increased rate of head growth during infancy in autism. JAMA. 2003;290: 393-394.

- Bauman ML, Anderson G, Perry E, Ray M. Neuroanatomical and neurochemical studies of the autistic brain: current thought and future directions. In: Understanding Autism: From Basic Neuroscience to Treatment. London: Taylor & Francis Group LLC; 2006: 303-322.

- Courchesne E, Carper R, Akshoomoff N. Evidence of brain overgrowth in the first year of life in autism. JAMA. 2003;290:337-344.

- Schumann CM, Hamstra J, Goodlin-Jones BL, et al. The amygdala is enlarged in children but adolescents with autism: the hippocampus is enlarged at all ages. J Neurosci. 2004:24:392-401.

- Fombonne E, Zakarian R, Bennett A, Meng L, McLean-Heywood D. Pervasive developmental disorders in Montreal, Quebec, Canada: preva – lence and links with immunizations. Pediatrics. 2006;118:139-150.

- Dales L, Hammer SJ, Smith NJ. Time trends in autism in MMR immunization in California. JAMA. 2002;285:1183-1185.

- Madsen KM, Hviid A, Vestergaard M, et al. A population-based study of measles, mumps and rubella vaccination and autism. N Engl J Med. 2002:347:1477-1482.

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Autism Questions and Answers for Health Care Providers. Available at: www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/pubs/autism/QA/sub4.cfm. Accessed January 11, 2010.

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Autism Overview: What we know. Available at: www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/pubs/upload/autism_ overview_ 2005.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2010.

- Boyle C, Van Naarden Braun K, Yeargin-Allsopp M. The prevalence and the genetic epidemiology of developmental disabilities. Butler M, Meany J, eds. In: Genetics of Develop mental Disabilities. London: Informa Healthcare; 2004:716-717.

- Muhle R, Trentacoste V, Rapin I. The genetics of autism. Pediatrics. 2004;113:472-486.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2004:65-78.

- National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities. Prevalence of the Autism Spectrum Disorders in Multiple Areas of the United States, Surveillance Years 2000 and 2002. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/dd/addm prevalence.htm. Accessed January 11, 2010.

- Autism Speaks. Autism Fact Sheet. Available at: www.autismspeaks.org. Accessed January 11, 2010.

- The Nancy Lurie Marks Family Foundation. DTermined Program for repetitive tasking and familiarization in dentistry. Available at: www.nlmfoundation.org/media.htm. Accessed January 11, 2010.

- Klein U, Nowak AJ. Characteristics of patients with autistic disorder (AD) presenting for dental treatment: a survey and chart review. Spec Care in Dentist.1999:19:200-206.

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Practical Oral Care for People with Autism. Available at: www.nidcr.nih.gov/OralHealth/Topics/DevelopmentalDisabilities/PracticalOralCarePeopleAutism.htm. Accessed January 11, 2010.

- Social Stories. Available at: www.polyxo.com/socialstories/introduction.html. Accessed January 11, 2010.

- Healing Thresholds. Social Stories Therapy for Children with Autism. Available at: http://autism.healingthresholds.com/therapy/social-stories. Accessed January 11, 2010.

- Kids Can Dream Autism Website. Home and School Social Stories. Available at: www.freewebs.com/kidscandream/page13.htm. Accessed January 11, 2010.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. February 2010; 8(2): 54-57.