Oral Health Risks Among College Students

Tailoring preventive education to address this population’s needs may help improve both oral and systemic health.

This course was published in the July 2014 issue and expires July 31, 2017. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss college students’ lifestyle factors that may affect their oral health.

- Identify ways to mitigate oral health risks in this population.

- Outline strategies for improving prevention efforts with college-age adults.

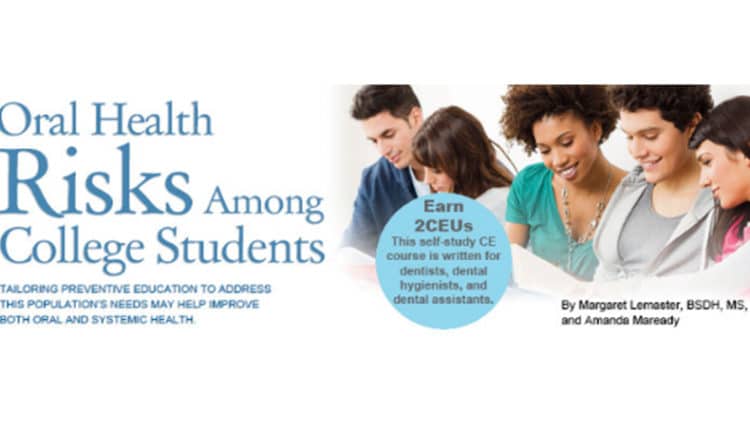

ALCOHOL ABUSE

The oral health risk factor that is perhaps most often associated with college students is excessive alcohol consumption. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) reports that four out of five college students regularly consume alcohol, and that half of these students binge drink.2 Binge drinking is defined by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as a pattern of drinking that brings a person’s blood alcohol level to 0.08 or higher (Figure 1). These levels are reached after a man has consumed five drinks and a woman has had four drinks within a span of 2 hours.

A blood alcohol content card is a helpful resource that can be given to college students—many of whom are unaware of how quickly alcohol affects them. This informative card can fit into a wallet and helps individuals determine how much alcohol is in their bloodstream based on type of drink, body weight, and gender. In a study by Hingson et al3 that included more than 3,000 participants, 68% of those age 18 to 25 went over the NIAAA’s daily or weekly drinking guidelines, but only 34% were asked about their drinking habits by a medical professional.

Identifying risky drinking behaviors and providing education are key to preventing future alcohol-related illnesses. Young adults do not often confide in health care providers concerning alcohol use for fear of parental notification. In order for patients to accurately report their alcohol use, dental hygienists should emphasize that health information is confidential—including social behaviors. Information discussed during the appointment is never shared with an adult, unless the patient specifically signs a release of health information.

Once the risk level is determined, the dental hygienist needs to educate the patient about the increased risk for dental caries due to alcohol-induced xerostomia—for which patients are advised to chew xylitol gum three times daily. Chewing gum that includes xylitol, a nonfermentable sugar alcohol, is an easy-to-use oral hygiene aid that creates an unfavorable environment for cariogenic bacteria, such as Streptococcus mutans.

The combination of alcohol and sugar consumption is especially prevalent among college students due to a popular alcoholic beverage called “jungle juice”—a sugary fruit punch laced with rum, gin, vodka, or a combination of the three.4 Late-night college party drinking, during which the likelihood of brushing one’s teeth is low, creates a hospitable environment for biofilm growth. For those with additional caries risk factors, recommending a fluoride mouthrinse in addition to daily brushing with fluoride toothpaste and the professional application of topical fluoride varnish or gel may be appropriate.

TOBACCO

Tobacco use is a major risk factor for caries, xerostomia, and periodontal diseases among college-age adults. Tobacco use on college campuses has evolved to include cigarettes, cigars, smokeless tobacco, and hookah pipe smoking. In addition, social smoking is on the rise among US college students.5 A social smoker uses tobacco with peers in social situations, discounting the notion of nicotine dependence. Many college-age adults may not equate social smoking with “being a smoker;” therefore, it is important for oral health professionals to discuss social smoking with patients while reviewing their health history forms.

A 2004 survey of 120 US universities conducted by the Harvard School of Public Health found that 51% of all student smokers claimed to be social smokers.5 The survey concluded that although social smoking was not conducted with the same frequency or intensity as traditional smoking, the intent and attempts to quit were much lower. Dental hygienists must recognize this subtle difference in order to educate their patients that social smoking is still a risk for oral cancer and caries. By encouraging young adults to quit tobacco use during these experimental social stages,6 dental hygienists can help reduce the risk of this patient population becoming chronically dependent on this addictive substance.

With the heightened awareness of cigarettes’ harmful health effects, many individuals—specifically college-aged adults—are searching for a more socially acceptable alternative. That substitute, for many, is hookah—a water pipe through which tobacco is inhaled (Figure 2). Many college students believe tobacco use via a hookah is less potent than tobacco in cigarettes, due to the hookah tobacco being filtered through water prior to reaching the user—and is therefore “purified” tobacco.7 However, this is not true—the water is a means to convert the smoke into a form of tobacco more easily inhaled.

Because of the misconception that hookah use is safer than cigarette use, a comparison of carcinogenicity between hookah and cigarettes should be specifically addressed with college students. A 2011 study conducted with 744 students at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond found that 20.3% of those interviewed had smoked a hookah within the past month.8 Of these students, 93% were under the age of 23.8 Due the misconception that it is mostly water and not really smoking, the use of a hookah tends to attract young people who have never used tobacco in the past. The concern with this impressionable demographic of nonsmokers is that the hookah will eventually lead them to seek out other forms of tobacco, thus increasing their odds of developing chronic tobacco-related diseases. The hookah serves as a gateway to smoking marijuana as the same pipe may be utilized for both substances.9

MARIJUANA

Marijuana use has surged in popularity throughout college communities, due in part to the recent legalization of marijuana use in Washington and Colorado. Since this legislation’s passing, the University of Colorado at Boulder has had a 33% increase in out-of-state applications, although the school said this statistic is unrelated to cannabis legalization—rather, it is associated with an updated application system for new students.10

The national study Monitoring the Future, conducted from 1975 to 2012, showed that 33.2% of college students smoke marijuana every year.11 More than 20% reported using marijuana within the past month. Similar to alcohol use, many college-age patients may not fully disclose marijuana use with their oral health professionals. Motivational interviewing is a judgment-free technique that may assist in getting patients to disclose their drug habits. Explaining the oral health consequences of habitual cannabis use should be included in oral health instruction if the patient indicates regular smoking. These effects include chronic gingival enlargement and “cannabis stomatitis,” which is similar to nicotine stomatitis.

There are also risks involved in treating patients who present to dental appointments under the influence of marijuana. Titsa and Ferguson12 report that patients who are high during an appointment may experience paranoid, psychotic thoughts, dysphoria, and acute anxiety. Administering local anesthesia containing epinephrine to patients who are under the influence of marijuana is contraindicated because of the increased heart rate commonly experienced by cannabis users.12

ELECTRONIC CIGARETTES

Electronic cigarettes, or e-cigarettes, are also becoming popular with the college student set. Composed of a cartridge containing nicotine and propylene glycol, an atomizer, and a battery, e-cigarettes are smoked through an atomizer that vaporizes the liquid when it comes through the mouthpiece (Figure 3).13 E-cigarettes do not contain tobacco, but rather the vapor disperses the nicotine without smoke or carbon dioxide. The nicotine cartridges are available in different flavors, which is appealing to young people.14,15 E-cigarettes are not currently regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration, and there is little research available about the short- and long-term effects on oral or systemic health. College students should be advised that they are taking a risk by engaging in e-cigarette smoking, or vaping, as adverse health effects are possible. Also, there is concern that regular users may develop a nicotine addiction that will lead them to try traditional tobacco products.

ORAL PIERCINGS

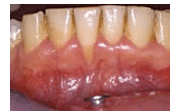

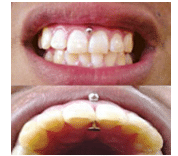

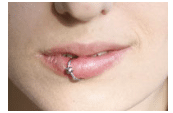

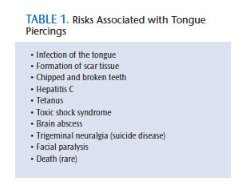

Oral piercings, which remain popular with young adults, come with a significant set of dental risk factors. Tongue and lip piercings can cause significant harm to oral structures, resulting in tooth fractures, tooth chipping, and abrasion (Table 1), as a result of continuous contact between metal and enamel surface during mastication and speech. Wear to the teeth and gingiva may also be caused by habitual movements, such as biting, rolling, or striking the piercing against the lingual surfaces of anterior teeth.16 Plaque and biofilm control on the surface of the piercing can be difficult—especially for individuals with tongue piercings. Oral health professionals should advise patients with oral piercings to remove their jewelry during meals, and to clean the metal regularly by soaking it in a hydrogen peroxide solution. Another oral condition caused by oral piercings is gingival recession (Figure 4). In 2006, Leichter and Monteith17 reported that people with lip piercings (Figure 5) were 7.5 times more likely to have recession than those without oral piercings.

In the past, oral piercings were usually seen on the lips and tongue. Recently, oral piercing placement has become more diverse to include locations such as the buccal mucosa, uvula, and the frenum attachments of the tongue and labial mucosa. The newest piercing, known as the “trans-gum” piercing (Figure 6), perforates either the interdental papillae or attached gingiva depending on the location. Regardless of location, oral piercings remain a local risk factor. To experimental college-age adults, oral piercings appear to be a harmless form of self-expression. However, their harmful effects on the teeth and periodontium far outnumber their hip factor.

NUTRITION

Poor nutrition is another caries risk factor commonly associated with college-age patients. Barriers to nutritious food choices include limited financial resources and lack of kitchen access while living in a dormitory. Budgeting may be new to some college students, who may be more concerned with spending money on tuition and textbooks vs healthy foods—which are often more expensive than less-healthy options and difficult to access. In addition to financial strain, microwaves are typically the only option for cooking while living in residence halls, which limits healthy meal options. Lack of healthy choices, especially during the freshman year of college, has led to the common phenomenon of gaining weight, known as “the freshman 15.”18 Many colleges have recognized this problem and are working to improve the health of their students by incorporating healthy eating programs into dining halls. Old Dominion University, in Norfolk, Virginia, launched a “Healthy for Life” program that has introduced vegetarian, vegan, gluten-free, low-fat, and low-sodium options for their students. The program also provides nutritional labeling, small portions, a section for fresh fruits and vegetables, and a full salad bar.

The detrimental effects that sugary soft drinks have on oral health are well known. These carbonated beverages—along with energy drinks, specialty coffees, and sports beverages—contain high levels of sugar, which may also contribute to tooth wear. Students may overlook the nutritional information of the beverages they consume. A standard 16-ounce energy drink has up to 54 g of sugar; a specialty coffee with whipped cream has anywhere from 45 g to 81 g of sugar; and a 20-ounce sports drink has 35 g of sugar and 35 g of carbohydrates. The latter is widely available on college campuses and widely consumed by students.

A large-scale study conducted by the CDC asked more than 25,000 American adults about their energy drink and sports drink consumption. Researchers found that age was the largest determinant of beverage intake—participants between the ages of 18 and 24 drank the most energy drinks and sports drinks. Of those young adults surveyed, 23.5% consumed three or more of these beverages on a weekly basis.19 Popularity of these drinks has surged, as many young adults crave the sugar and caffeine found in these beverages in order to function for academic and social activities. Such dependence is not healthy, however, and could lead to sleep disorders.

LACK OF SLEEP AND STRESS

Lack of sleep and stress are two health risk factors that affect many people today, especially college students. High expectations of performance may cause an emotional and physiological response. During times of limited sleep and high stress, young adults may neglect basic hygiene routines and increase their tobacco and alcohol use to ease anxiety.20 Dental effects include a decrease in salivary flow as part of a stress-induced sympathetic nervous system response,21 which can increase the risk for caries.

High stress levels have also been linked to gingival inflammation. A 2010 Swedish study monitored the salivary components and plaque retention of 20 dental hygiene students to see what changes occurred during times of high stress. Samples were taken during final exam week, as well as 4 weeks post-exams. Researchers discovered that elevated levels of interleukin-6, an inflammatory cytokine, within the gingival crevicular fluid were found during high-stress periods.22 This suggests that stress can negatively affect oral health by initiating the inflammation process that leads to gingivitis.

CONCLUSION

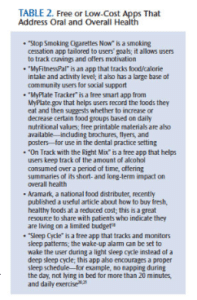

Healthy lifestyle choices support oral health. Young adults, specifically those of college age, may make poor lifestyle choices—including increased alcohol and tobacco use, oral piercings, poor diet, and lack of sleep—that may negatively affect their ability to achieve and maintain healthy periodontium. Oral health professionals, through proper patient education, guidance, and the recommendation of user-friendly apps (Table 2),18,23,24 can assist college-age students and recent college graduates shed newly acquired unhealthy habits. By educating patients about the risks associated with their lifestyle choices, clinicians can help young people maintain their oral health and prevent oral disease.

REFERENCES

- National Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics. Fast Facts: Back to School Statistics. Available at: nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=372. Accessed June 9, 2014.

- National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. College Drinking. Available at: niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol- health/special-populations-co-occurring-disorders/college-drinking. Accessed June 9, 2014.

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Edwards EM, Saitz R. Young adults at risk for excess alcohol consumption are often not asked or counseled about drinking alcohol. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:179–184.

- College Haze. The Best Jungle Juice Recipes. Available at: collegehaze.com/college-party/college-party-tips/the-best-jungle-juice-recipes. Accessed June 9, 2014.

- Moran S. Social smoking among US college students. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1028–1034.

- Jackson KM, Colby SM, Sher KJ. Daily patterns of conjoint smoking and drinking in college student smokers. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010;24:424–435.

- Morris DS, Fiala SC, Pawlak R. Opportunities for policy interventions to reduce youth hookah smoking in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:122–127.

- Cobb C, Ward K. Waterpipe tobacco smoking: an emerging health crisis in the United States. Am J Health Behav. 2010;34:275–285.

- Warnakulasuriya S. Waterpipe smoking, oral cancer and other oral health effects. Evid Based Dent. 2011;12:44–45.

- USA Today. Weed law not slowing Colorado college application rates. Available at: usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/01/15/weed-law-app-rates/4476081/. Accessed June 9, 2014.

- Monitoring the Future. 2013 Press Release. Available at: monitoringthefuture.org. Accessed June 9, 2014.

- Titsas A, Ferguson MM. Impact of opioid use on dentistry. Aust Dent J. 2002;47:94–98.

- Ayers JW, Ribisl KM, Brownstein JS. Tracking the rise in popularity of electronic nicotine delivery systems (electronic cigarettes) using search query surveillance. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:448–453.

- Food and Drug Administration. FDA warns of health risks posed by e-cigarettes. Available at: fda.gov/ downloads/forconsumers/ consumerupdates/UCM173430.pdf. Accessed April 21, 201

- Henry R, Henderson R. The rise of e-cigarettes. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2014;12(5):46–50.

- Plessas A, Pepelassi E. Dental and periodontal complications of lip and tongue piercing: prevalence and influencing factors. Aust Dent J. 2012;57:71–78.

- Leichter JW, Monteith BD. Prevalence and risk of traumatic gingival recession following elective lip piercing. Dent Traumatol. 2006;22:7–13.

- Gropper S, Lord D, Watts A, Arsiwalla D, Simmons KP. Perceived stress, eating regulation behaviors, and body mass index, body weight and percent body fat relationships over the first two years of college. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2013;113(9):A36.

- Aramark. Nutrition on a Budget. Available at: campusdish.com/NR/rdonlyres/B268EAFB-CD47-4224-AC07-04EF103F9601/0/040614_Budget.pdf. Accessed June 9, 2014.

- Park S, Onufrak S, Blanck HM, Sherry B. Characteristics associated with consumption of sports and energy drinks among US adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2010. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113:112–119.

- Reners M, Brecx M. Stress and periodontal disease. Int J Dent Hyg. 2007;5:199–204.

- Queiroz CS, Hayacibara MF, Tabchoury CP, Marcondes FK, Cury JA. Relationship between stressful situations, salivary flow rate and oral volatile sulfur-containing compounds. Eur J Oral Sci. 2002;110:337–340.

- Johannsen A, Bjurshammar N, et al. The influence of academic stress on gingival inflammation. Int J Dent Hyg. 2007;8:22–27.

- Buboltz WC, Soper B, Brown F, Jenkins S. Treatment approaches for sleep difficulties in college students. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 2002;15(3):229–237.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. July 2014;12(7):55–59.