MONKEYBUSINESSIMAGES / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

MONKEYBUSINESSIMAGES / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Interest in Teledentistry Continues to Grow

The COVID-19 pandemic thrust teledentistry into the spotlight, illuminating its many advantages in increasing access to care.

This course was published in the May 2022 issue and expires May 2025. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the role of teledentistry in accomplishing public health initiatives.

- Discuss the evolution of teledentistry.

- Note the impact of COVID-19 on the adoption of teledentistry.

- List the requirements and benefits of teledentistry.

Teledentistry is gaining ground in many states as a strategy to reach patients who would otherwise not receive care—especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Through the use of school nurses, registered nurses, dental hygienists, dental therapists, and other trained allied healthcare professionals, teledentistry enables traditionally underserved populations to receive oral healthcare services.1,2 Many states have implemented teledentistry through the use of oral health professionals, increasing access to care for the most vulnerable populations and enabling reimbursement via Current Dental Terminology (CDT) codes.

Supporting Public Health Initiatives

Many Americans struggle to access professional dental care for myriad reasons. Public health initiatives are designed to address these issues. Several such initiatives, including the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), and Institute of Oral Medicine (IOM), impact the implementation of teledentistry as their purpose is to improve the equity and efficiency of medical and dental care through the improvement and expansion of informatics.

Concerns have been raised regarding the delivery of telehealth and how it meets HIPAA criteria. In 1996, the HIPAA established rules to ensure privacy protection when sharing information between providers.3 In order to comply with HIPAA regulations, a secure system to store patient information is necessary. This may present barriers for some practices, as federal regulations for ensuring the confidentiality, security, and back-up of patient records must be followed. Practices that are already using electronic health record systems should not have difficulty meeting these standards.4 With the goal of reducing the cost of care, improving oral health, and preventing oral diseases, teledentistry remains an important public health tool so while adhering to HIPAA regulations may present an extra step, it can be efficiently addressed.

In 2006, the IHI released the “Triple Aim“ framework to improve health system outcomes, and the use of teledentistry is key in supporting this mission. The three goals are:

- Maximize patients’ experiences in healthcare settings

- Improve the health of all Americans

- Decrease the cost of healthcare

The IHI focuses on the use of innovative ideas, such as patient-centered medical homes, payment restructuring, and integration of technology, to achieve these goals.5 The use of teledentistry during the COVID-19 pandemic and the resultant positive patient satisfaction surveys demonstrate that this remote model is an important component to meeting the Triple Aim goals.6,7

Teledentistry—as an integrated part of on-site dentistry—also supports the IOM’s charge to improve the oral health of the most vulnerable populations in the United States. The IOM advocates for the use of appropriate technology; supervision and collaboration of remote oral health professionals; monitoring of off-site patients; and enabling oral health professionals to practice at the fullest extent of their education and training. The IOM aims to minimize or eliminate oral health disparities related to age, gender, race, ethnicity, creed, socioeconomic status, insurance status, and ability to pay.8

Evolution of Teledentistry

The advent of teledentistry began with the US military nearly 30 years ago. In 1994, a dentist at the Fort McPherson Army Base in Atlanta sent color images to a periodontist in Fort Gordon, Georgia—120 miles away. Through this sharing of images, 15 patients were referred to the periodontist for periodontal surgery. Post-operative care was provided at the Fort McPherson Army Base with images consistently shared with the periodontist to ensure successful follow up. This experience led to the implementation of additional military-based teledentistry projects across the globe.9,10

In 2003, Apple Tree Dental—a nonprofit organization based in Minnesota that focuses on overcoming barriers to dental care and integrating oral health with overall health—began using teledentistry to increase access to care in underserved communities, especially among children and seniors. Under one of Apple Tree Dental’s models, a dental hygienist visits multiple group homes and a day center for adults with special needs to provide preventive services and help patients maintain their oral health. Then, the dental hygienist forwards the digital images, radiographs, and patient charts to the off-site collaborative dentist who completes the examination remotely and develops a treatment plan. Most patients receive all of their recommended preventive and restorative care on-site in their home community, and only patients needing more advanced treatment need to travel to a dental clinic. Prior to contracting with Apple Tree Dental, the residents received oral healthcare services in a hospital setting, which often involved long wait times and high cost. When these patients with special needs are treated in their own settings, their oral health is more likely to be stabilized, reducing the need for high-cost interventions. Minnesota’s state law also allows for advanced dental therapists to provide care directly to patients, further supporting the teledentistry model of care.11

In 2010, Paul Glassman, DDS, MA, MBA, and his colleagues at the University of the Pacific in San Francisco, developed the first virtual dental home (VDH). Using telehealth technology, the VDH aids in the delivery of oral healthcare to schools and long-term care facilities. Designed to link allied dental personnel with community-based programs and facilities, the VDH enables patients to seek care closer to their own neighborhoods, reducing the cost and barriers presented by travel. Care is provided by dental team members under the remote supervision of a dentist. These community sites also provide education and social services that lead to early intervention and prevention of oral diseases. Taking a cue from California, other states—including Alaska, Arizona, Hawaii, Ohio, and Oregon—have used the VDH model to create similar programs in their respective areas.12,13

The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic

While teledentistry is not new, its implementation certainly grew during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many states attempted to reduce direct contact exposures through strict regulations and social distancing policies. Personal protective equipment also became scarce, impeding the ability of oral health professionals to provide dental care.14,15

When dental practices were advised to stop treating patients, with the exception of emergency cases, some practices began incorporating some facets of teledentistry in order to stay in touch with their patients. Applications such as Apple FaceTime, Skype, Facebook Messenger video chat, Google Hangouts video, and Zoom were determined to be “safe” modes of mobile dentistry delivery.16 Practitioners, especially those who do not use electronic health record platforms, were finally able to reach out to community members living in rural and urban areas via teleconferencing, video chat, and cell phone or computer pictures.

The systematic deferral of nonurgent treatment required by the pandemic has created a wave of patients who previously had minor active oral disease who now need immediate intervention to prevent further loss of oral structures. Particularly in the older adult population, the preservation of oral health and early intervention of disease states are crucial to maintaining oral and systemic health. Teledentistry can play an important role in preventing oral diseases from worsening due to nonintervention.

Modes of Delivery

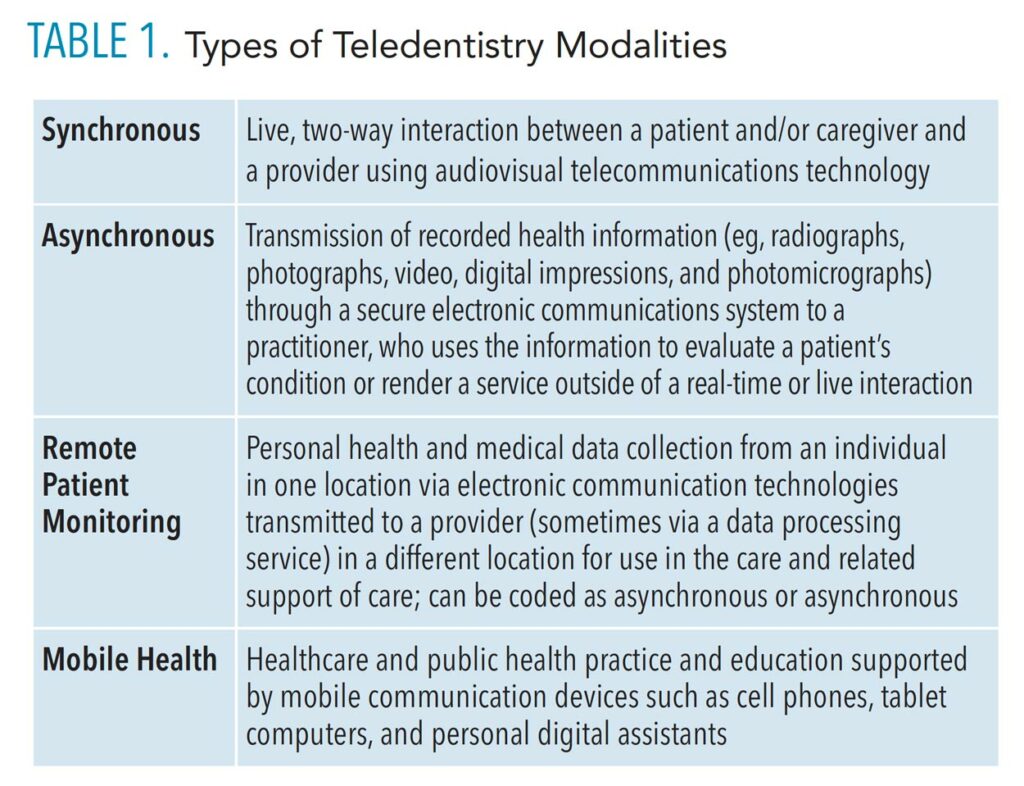

Depending on the population and community served, teledentistry is a versatile model that can be delivered in a variety of situations, populations, and sites. Some of the options include the following considerations:

- How the information is transmitted

- When and if the visit will include real time (synchronous) consultation

- Whether a store-and-forward method (asynchronous) is appropriate

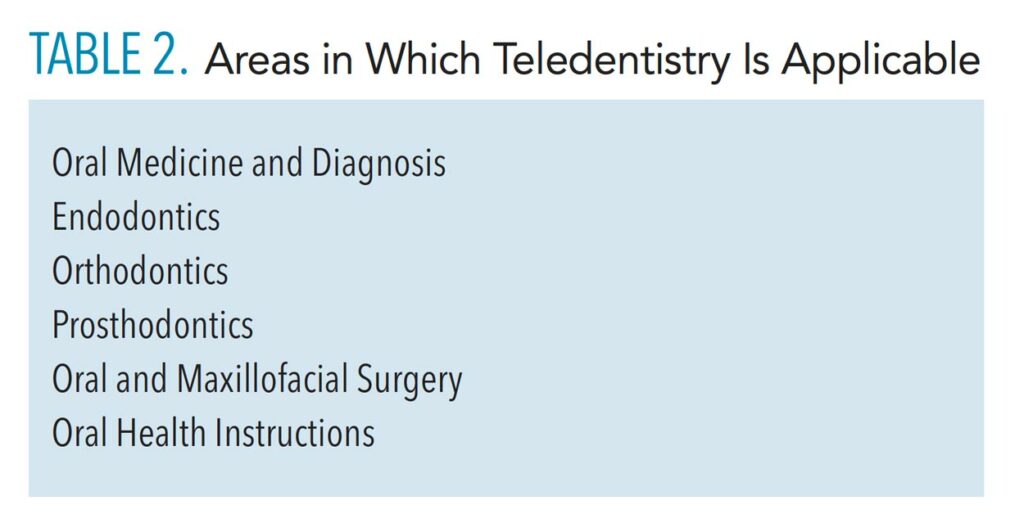

Table 1 provides more details on these options. Additionally, teledentistry can be applied to a variety of dental situations and types of care, such as telescreening, telediagnosis, teletriaging, and telereferral, reducing the number of visits required to address specific situations (Table 2).12,13

![TABLE 1. Types of Teledentistry Modalities]() Current Dental Terminology

Current Dental Terminology

In 2018, the American Dental Association’s CDT included two teledentistry codes:17,18

- D9995 for synchronous (live two-way, patient and provider interaction)

- D9996 for asynchronous (transmission of data to a provider for an offline assessment)

The oral health or general health professional, depending on state law and regulations, provides the teledentistry visit’s diagnosis and treatment plan, completes the coding, and completes any necessary documentation. Dental professionals must be licensed within the same state where the care is provided and all services rendered must be within the clinician’s scope of practice in the state where the care is received.19

Teledentistry visits are subject to state law, regulation, and licensure requirements. Each state has a Board of Dentistry website that provides more information on specific state regulations and practice acts. The American Dental Education Association also provides an at-a-glance comparison of what different states are doing in the teledentistry arena.20

Initially, only a few insurance companies reimbursed teledentistry services, but at the height of the pandemic, several began covering virtual visits.21 The reimbursement of dental services rendered through teledentistry varies widely from state to state. A patient’s insurance policy must be reviewed to determine whether it covers synchronous and/or asynchronous visits.

Technology Required

Technology enhances the way care is provided and how information is shared. Advancements in technology and pandemic changes allow for practices to go far beyond the walls of a dental clinic and into rural areas where access to care is most difficult. A variety of tools can be used for various teledental care models, including internet/Wi-Fi, cellphones, personal digital assistants, laptops, tablet devices, electronic medical record platforms, portable digital radiographs, health apps, and intraoral cameras for live stream or still photos.18 HIPAA regulations, however, must be followed when sharing patient data.

The use of teledentistry does not require a significant financial investment; programs can start out simply providing oral health education or remote patient monitoring with as little as an internet connection and/or cell phone.19 Programs designed to provide direct patient care such as fluoride and sealant application, prophylaxes, scaling and root planing, interim therapeutic restorations, or other services, will cost more due to the supplies required and regulations inherent to the sharing of patient information.

Teledentistry Benefits

A silver lining of the global pandemic is that teledentistry has gained immense ground in establishing acceptance with providers and patients. Many patients who received this innovative method of care delivery felt satisfied within five domains: patient satisfaction; ease of use; effectiveness, including increasing access to clinical services; reliability of the teledentistry system; and usefulness.22 The benefits of teledentistry include more efficient appointment scheduling, decreased wait lists, fewer emergency department visits, high patient acceptance, expanded access to care, more access to specialists, reduced patient anxiety, decreased overhead and patient care costs, more effective monitoring of patients, increased dental education outreach, and the ability to offer more services such as vaccinations.18,23–26

Challenges to implementing teledentistry remain, including weak internet connectivity in rural areas, lack of devices and Wi-Fi connection among some populations, low level of knowledge and training on the use of teledentistry and how to adhere to HIPAA regulations, and the need for direct-care procedures that may be necessary to address the patient’s complaint.

To reap the benefits of teledentistry, additional training for providers and buy-in from all parties are needed.27 Curricula and continuing education courses on the following subjects would help prepare those who are interested in working in teledentistry: medical and dental emergencies for clinicians practicing remotely; appropriate referrals, state laws, and regulations regarding scope of practice; patient management; prescription writing; and interprofessional collaboration.28–31

Opportunities abound for those interested in teledentistry and how it can help patients who may otherwise struggle to receive care to not only access the system, but to benefit from it.

References

- Braun PA, Budzyn SE, Chavez C, Barnard JG. Integrating dental hygienists into medical care teams: practitioner and patient perspectives. J Dent Hyg. 2021;95:6–17.

- Nayar P, McFarland KK, Chandak A, Gupta N. Readiness for teledentistry: validation of a tool for oral health professionals. J Med Syst. 2017;41:4.

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Available at: aspe.hhs.gov/reports/health-insurance-portability-accountability-act-1996. Accessed April 26, 2022.

- Fricton J, Chen C. Using teledentistry to improve access to dental care for the underserved. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist. psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1048.6167&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Accessed April 26, 2022.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. IHI Triple Aim. Available at: ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed April 26, 2022.

- Braun PA, Budzyn SE, Chavez C, Barnard JG. Integrating dental hygienists into medical care teams: practitioner and patient perspectives. J Dent Hyg. 2021;95:6–17.

- Alabdullah JH, Daniel SJ. A systematic review on the validity of teledentistry. Telemed J E Health. 2018;24:639–648.

- Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. Improving Access to Oral Health Care for Vulnerable and Underserved Populations. Available at: hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/publichealth/clinical/oralhealth/improvingaccess.pdf. Accessed April 26, 2022.

- Rocca MA, Kudryk VL, Pajak JC, Morris T. The evolution of a teledentistry system within the Department of Defense. Proc AMIA Symp. 1999;921–924.

- Fortich-Mesa N, Hoyos-Hoyos V. Applications of teledentistry in dental practice: a systematic review. Rev Fac Odonto Univ Antioq. 2020;32:77–88.

- Center for Health Workforce Studies. Case Studies of 6 Teledentistry Programs: Strategies to Increase Access to General and Specialty Dental Services. Available at: chwsny.org/our-work/reports-briefs/case-studies-of-6-teledentistry-programs-strategies-to-increase-access-to-general-and-specialty-dental-services. Accessed April 26, 2022.

- Glassman P. Improving oral health using telehealth connected teams and the virtual dental home system of care: program and policy considerations. Available at: utah.gov/pmn/files/圕.pdf. Accessed April 26, 2022.

- Domngues Martins M, Coelho Carrard V, Mello dos Santos C, Neves Hugo F. COVID-19—are telehealth and tele-education the answers to keep the ball rolling in dentistry? Oral Diseases. 2020;00:1–2.

- Abbas B, Wajahat M, Saleem Z, Imran E, Sajjad M, Khurshid Z. Role of teledentistry in COVID-19 pandemic: A nationwide comparative analysis among dental professionals. Eur J Dent. 2020;14:S116–S122.

- Nichols KR. Teledentistry Overview: United States of America. Available at: https://journals.ukzn.ac.za/index.php/JISfTeH/article/view/⺔/닶. Accessed April 26, 2022.

- American Dental Association. COVID-19 Coding and Billing Interim Guidance. Available at: 7dds.org/uploads/files//ADA% 20COVID%20Coding%20and%20Billing%20Guidance%2004.03.20.pdf. Accessed April 26, 2022.

- American Dental Association. D9995 and D9996—ADA Guide to Understanding and Documenting Teledentistry Events. Available at: mouthhealthy.org/~/media/ADA/Publications/Files/ADAGuidetoUnderstandingandDocumentingTeledentistryEvents_v3_떕Aug20210804t165513.pdf?la=en. Accessed April 26, 2022.

- Wilson R. Ethical issues in teledentistry: following the American Dental Association principles of ethics and code of professional conduct. J Am Dent Assoc. 2021;152:176–177.

- American Dental Association. ADA Updates Teledentistry Policy. Available at: ada.org/publications/ada-news/떔/november/ada-updates-teledentistry-policy. Accessed April 26, 2022.

- American Dental Education Association. Teledentistry State Statutes and Regulations. Available at: cqrcengage.com /adea/teledentistryregulations?0. Accessed April 26, 2022.

- Humana. Humana policy guidance for telehealth. Available at: humana.com/provider/coronavirus/telemedicine. Accessed April 26, 2022.

- Rahman N, Nathwani S, Kandiah T. Teledentistry from a patient perspective during the coronavirus pandemic. Br Dent J. 2020;1–4.

- Alabdullah JH, Daniel SJ. A systematic review on the validity of teledentistry. Telemed J E Health. 2018;24:639–648.

- Alabdullah JH, Van Lunen BL, Claiborne DM, Daniel SJ, Yen CJ, Gustin TS. Application of the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology model to predict dental students’ behavioral intention to use teledentistry. J Dent Educ. 2020;84:1262–1269.

- National Conference of State Legislatures. Increasing Access to Health Care Through Telehealth. Available at: ncsl.org/research/health/increasing-access-to-health-care-through-telehealth.aspx. Accessed April 26, 2022.

- Maqsood A, Sadiq MSK, Mirza D, et al. The teledentistry, impact, current trends, and application in dentistry: a global study. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:5437237.

- Anderson J, Singh J. A case study of using telehealth in a rural healthcare facility to expand services and protect the health and safety of patients and staff. Healthcare. 2021;9:736.

- Braun PA, Budzyn SE, Chavez C, Barnard JG. Integrating dental hygienists into medical care teams: practitioner and patient perspectives. J Dental Hyg. 2021;95:6–17.

- McLeod CD. Knowledge, attitudes, and applications of teledentistry among dental and dental hygiene students. Available at: file:///Users/kristen/Downloads/McLeod_unc_깉M__%20(2).pdf. Accessed April 26, 2022.

- Nayar P, McFarland KK, Chandak A, Gupta N. Readiness for teledentistry: validation of a tool for oral health professionals. J Med Syst. 2017;41:4.

- Gadupudi SS, Nisha S, Yarramasu S. Teledentistry: a futuristic realm of dental care. International Journal of Oral Health Sciences. 2017;7:63.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. May 2022;20(5):26-28,31.