PIKSEL / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

PIKSEL / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

The Hallmarks of Alzheimer Disease

By better understanding the risk factors and brain changes associated with this disease, clinicians will be well-prepared to provide dental care.

Part 1 of a two-part series: Part two will discuss oral care assistance for individuals with Alzheimer disease as well as necessary modifications to dental appointments and will appear in a future issue.

This course was published in the September 2022 issue and expires September 2025. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 750

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the risk factors and signs associated with Alzheimer disease (AD).

- Discuss the connection between periodontal infection and the brain infection seen in patients with AD.

- Consider the lost and retained abilities related to brain changes among individuals with AD.

Dental professionals routinely provide care for individuals with dementia. Characterized by abnormal brain changes severe enough to interfere with daily life, dementia often causes memory loss, inability to use language, and challenges with problem-solving.1 Alzheimer disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia, accounting for 60% to 80% of all types.1 In 2019, dementia affected 9.8% of Americans ages 70 and older.2 In 2022, approximately 6.5 million Americans ages 65 and older live with AD.3

Changes in the brain are responsible for AD. Amyloid beta-peptide plaques form in neuron synapses, interfering with impulse transmission.4,5 Within the neurons, tangles of tau protein develop.4 Accumulation of plaques between neurons coupled with the tau found inside the neurons interfere with the neurons’ ability to communicate. As a result, the neurons degenerate and the brain shrinks.6 This affects the individual’s ability to think, remember, make decisions, and function independently.6 Plaques and tangles form through inflammation and exposure to inflammatory mediators, such as TNF-a, IL-1B, and IL-6.7 These accompany any inflammatory disease, including periodontitis. Inadequate biofilm removal is the precursor to this process. As such, patients must be educated on the harms of oral biofilm and the importance of removing it.

Risk Factors for Alzheimer disease

Several factors contribute to the risk of developing AD, including advanced age, genetics, and environmental exposures.8 The gene with the strongest impact on AD risk is APOE-e4. Between 40% and 65% of people with AD have the APOE-e4 gene.8 Environmental exposures may include air pollution, pesticides, and vitamin D deficiency; however, these require further research to validate their connections to AD. Previous damage to the brain (eg, traumatic brain injuries) also increases AD risk.8 The risk of AD also increases when the blood vessels that supply the brain are damaged, such as in hypertension, stroke, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, and high cholesterol.8

Level of education poses a risk for AD. Individuals who completed more years of formal education are at reduced risk of AD than those with fewer years of formal education.4 This connection is not well understood but may be linked to the development of neuronal connections in the brain from continued education compared to those who have less education. Inadequate sleep or poor sleep quality, excessive alcohol use, depression, and hearing impairment are also possible risk factors currently under investigation.4

Periodontitis and infection with the Gram-negative bacteria Porphyromonas gingivalis were identified as risk factors for AD as far back as 2006.5,9 The National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research states that 42% of adults ages 30 and older have periodontitis.10 This puts a large percentage of the population at risk for AD. P. gingivalis can be found in the brain decades before cognitive decline is observed.9 AD-related brain changes are thought to begin 20 years or more before symptoms present.4 A 2017 study of 9,291 individuals with periodontitis determined that the presence of periodontitis for 10 years or more led to a 70% higher risk of developing AD compared to not having periodontitis.7 This finding emphasizes the importance of stabilizing periodontal diseases in adults, especially those at increased risk for AD. The invasion of brain tissue by P. gingivalis is not a result of poor oral care after AD is diagnosed.9 Poor oral care is the precursor to and sustainer of periodontitis.

P. gingivalis produces a virulence factor known as gingipain. When secreted, gingipains play a critical role in host colonization, inactivate the host’s inflammatory response, and destroy tissues.9 P. gingivalis travels from the mouth to the brain through a variety of pathways. The organism may enter the blood stream during a bacteremia, which is frequently caused by toothbrushing, flossing, chewing, and dental procedures.9,11 During a bacteremia, the organism travels to other body systems, including the coronary arteries, placenta, liver, brain, and cerebrospinal fluid.9 P. gingivalis can also infect monocytes that are recruited to the brain, directly infecting and damaging endothelial cells that protect the blood-brain barrier and spreading through cranial nerves. After entry into the brain, the spread of the organism from neuron to neuron is slow. The presence of P. gingivalis in the brain increases the production of amyloid beta, a component of the plaques that contribute to AD. Both P. gingivalis and gingipains are found in the brain tissue of those with AD. P. gingivalis is also found in the cerebrospinal fluid of living individuals with AD.9

Saliva tests have been designed to detect the oral microorganisms capable of causing periodontal diseases, as well as other systemic conditions. Saliva testing may be an excellent pathway to early identification for those with AD risk factors.

Signs of Alzheimer Disease

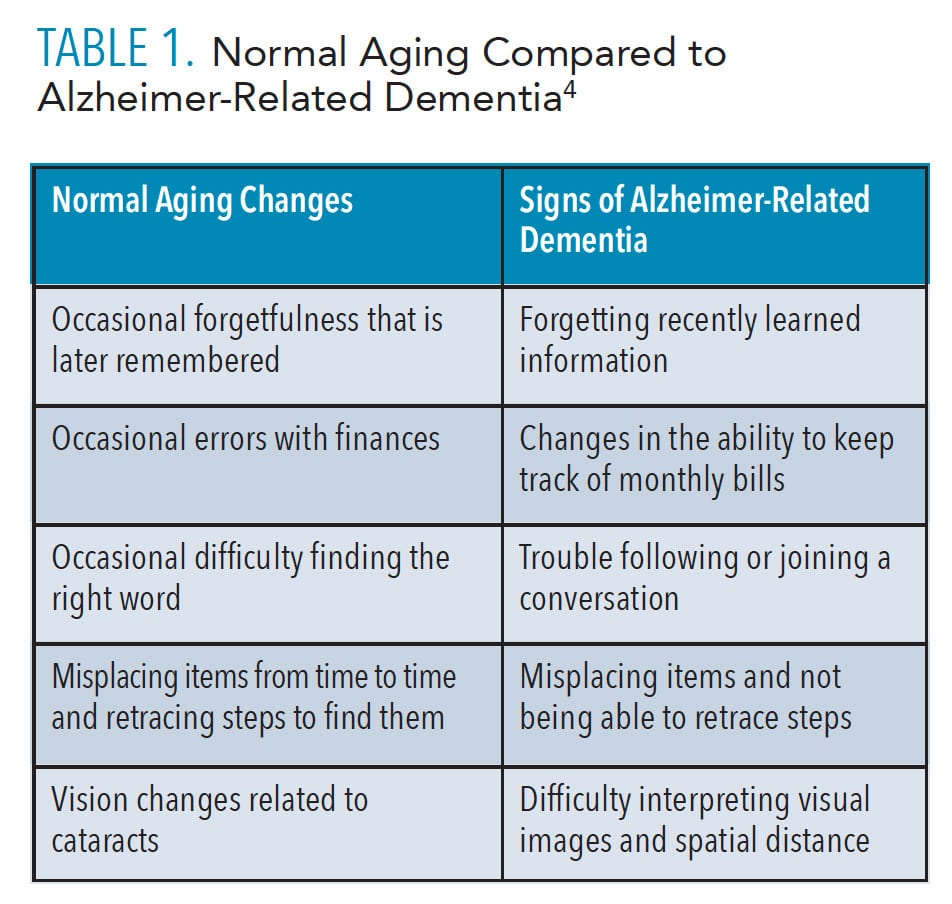

Aging brings cognitive changes that may be unrelated to AD. Table 1 compares normal aging changes to signs of Alzheimer-related dementia.4 For those experiencing normal aging changes, it may be a relief to find these cognitive changes are typical of the aging process. It is also important for dental professionals to know the difference between normal aging and the signs of AD.

There are four truths about dementia that differ from normal aging: 1) at least two parts of the brain are actively dying, 2) the structure of the brain is changing, 3) the condition is chronic, and 4) dementia is terminal.12 During this process, signs of AD will surface, including changes in memory, language, vision, and sensory perception. Individuals with AD eventually lose the ability to care for themselves as initiating and fulfilling a skill, tool manipulation, and sequencing become highly challenging.13

Those with AD lose memory and details of recent events while long ago memories, emotional memories, and motor memories are retained. This explains why individuals living with AD like to retell stories from their past and can complete tasks using motor skills. Language is greatly affected due to the shrinking of the brain. Individuals living with AD find it difficult to retrieve the right word during conversations. They may accidentally mix up words or add words to their sentences. Language becomes vague instead of descriptive and is limited to short, simple phrases. Preserved language skills include singing, use of forbidden words, and automatic responses, such as greetings. Individuals living with AD struggle to understand verbal language, but may retain the ability to interpret facial expressions, tone of voice, and other nonverbal cues.13 This emphasizes the need for simple language and awareness of body language when communicating with those with AD.

While memory changes are commonly associated with AD, other changes may be overlooked or dismissed. Those with AD lose peripheral vision, leading to sight only in middle of the field of vision. Object recognition and purpose become less familiar.13 Object recognition and purpose are needed to decipher how to perform a task, such as rinsing after toothbrushing. If an individual with AD thinks the cup contains a beverage instead of mouthrinse, the individual is likely to swallow the liquid instead of swishing with it. This creates a need for direct supervision. Depth perception worsens as vision loss accelerates. As AD progresses, the field of vision narrows, leading to a small amount of vision in only one eye at a time. This is called monocular vision.

Hearing is not affected by dementia-related brain changes. Sensory changes include the loss of body and position awareness as well as the ability to locate and express pain. Sensation remains active and even heightened in some areas of the body, including the mouth, lips, tongue, hands, feet, and genitalia.13 These heightened areas can elicit either a positive or negative response when touched. Oral health professionals should be prepared for exaggerated reactions when touching the mouth, lips, and tongue of a patient with AD.

Individuals with dementia may experience changes in personality and mood. Depression is the most common mood disorder among this population.14 The onset of depression can be a warning sign of AD. If other signs of AD are present, an evaluation by a physician is prudent. A positive association between depression and caries also exists.15 The exact etiology is not well understood, but prevention strategies can be implemented if depression is diagnosed. Anxiety can be present early in the course of AD and is more commonly identified in those diagnosed before the age of 65.14

Stages of Alzheimer Disease

Early onset of AD begins before the age of 65 and late onset occurs at age 65 and older.4 Early onset AD is thought to have strong genetic connections, while late onset AD is influenced by environmental factors.5 The first stage of AD is preclinical where measurable biomarkers indicate the earliest signs of AD, but symptoms have not developed. Biomarkers of AD are found in the cerebrospinal fluid and seen on positron emission tomography (PET) scans during the preclinical stage. Mild cognitive impairment is the next stage characterized by subtle symptoms, such as problems with memory, language, and thinking. About one-third of those with mild cognitive impairment develop AD within 5 years.4

Once dementia is established, noticeable changes occur that impair an individual’s ability to function in daily life.4 Those with mild dementia can function in many areas but are likely to require assistance with some activities to maximize independence and safety. The longest stage of AD, moderate dementia causes more problems with memory and language, increases feelings of confusion, and hinders individuals’ abilities to complete multistep tasks such as bathing and dressing. The final stage of dementia greatly diminishes the ability to communicate verbally. Individuals with severe dementia may require around-the-clock care and likely are not visiting the dental office for care unless it is pain related.

GEMS Classification of Abilities

The shift in skills and cognitive abilities can be categorized by a GEM brain change model developed by Teepa Snow, MS. One of the leading educators on dementia and its care in the United States and Canada, Snow is the founder of the Positive Approach to Care, whose mission is to enhance life and the relationships of those living with brain change by fostering an inclusive global community. Each stage of dementia has unique changes that can be grouped into six gemstones with the GEMS brain change model. These gemstones correlate to the stages of AD. A clear understanding of these changes might align dental professionals with the appropriate expectations for ability and cooperation of patients with dementia.

The first GEM is the sapphire. At this stage, the brain is healthy and cognition is optimal. Normal aging is evident in those who are in the sapphire stage. Second, the diamond stage reflects clear and sharp cognition when happy, but behavior can be cutting when distressed. Diamonds prefer the familiar and may resist change. These individuals need repetition and time to absorb new information. The emerald GEM stage displays flaws, such as missing one of every four words in a conversation, lacking safety awareness, and irrational thoughts. Strong emotional reactions may occur in the emerald stage when feeling fearful or having unmet needs. Changes in the amber GEM stage include increased sensitivity in areas such as the mouth, hands, and feet. Intolerance to discomfort in these areas may lead to resistance in activities involving the mouth, such as eating, taking medication, and oral hygiene. Ambers may refuse care or see someone who is trying to help them as threatening. Individuals in the ruby GEM stage have lost fine motor skills and need someone to guide their movements and transitions. They need assistance starting and stopping skills. The pearl GEM stage is near the end of life. The brain is losing the ability to control and heal the body. Difficulty breathing and swallowing is common.16 More information about the GEMS brain change model is available at: teepasnow.com. Sharing this information with family members and caregivers may allow them to understand the state of the disease better and assist them in best supporting the person with AD.

Diagnostic Procedures And Treatments

Primary care physicians usually diagnose AD while related specialists may include neurologists, geriatric psychiatrists, geriatricians, and neuropsychologists. In addition to reviewing the patient’s medical history, physicians use questionnaires, clinical exams, and brief assessments to evaluate thinking and memory function. Cognitive assessment tools evaluate the ability to learn and recall new information and measure changes in reasoning, problem-solving, planning, naming, comprehension, and other cognitive skills.4 In the early stages of AD, cognitive assessment is the main method to diagnose AD; however, it is inaccurate in approximately 50% to 60% of patients.17 Blood work is also a standard procedure in the beginning stages of the diagnostic process.

In May 2022, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) cleared the first in vitro diagnostic test to aid in the detection of AD. The Lumipulse G β-Amyloid Ratio 1-42/1-40 test detects amyloid plaques among those age 55 and older who are showing cognitive decline.18 During this test, cerebrospinal fluid is collected to determine the presence of amyloid plaques, similar to results revealed during a PET scan of the brain. Amyloid PET scans have been a standard tool for AD diagnosis but this additional test provides another option to identify the presence of amyloid plaques. Other imaging techniques include magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography to rule out other conditions in the brain.

Donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine, memantine, and memantine combined with donepezil are medications available to treat the symptoms of AD.4 These medications do not alter the course of the disease. Aducanumab, the first drug aimed at treating the disease process, was approved by the FDA in June 2021. Aducanumab was studied in people with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia due to AD and demonstrated the ability to reduce plaques in the brain. Controversy over this drug exists due to its limited ability to improve cognition and its high cost. Other treatment options for AD are aimed at improving quality of life, such as cognitive stimulation, music-based therapies, and cognitive behavioral therapy. These treatments may help to reduce behavioral symptoms such as depression, apathy, wandering, sleep disturbances, agitation, and aggression.4 Mood disorders can be treated with prescription medications, which may increase risk for xerostomia.

Addressing Porphyromonas Gingivalis and Gingipain Inhibitors

As oral bacteria increase the risk for AD, controlling them should likely be part of the AD treatment protocol. Such a protocol is not currently available, but research is underway. Broad-spectrum antibiotics do not protect against P. gingivalis-induced cell death, nor do they clear P. gingivalis from the brain. P. gingivalis rapidly develops resistance to broad-spectrum antibiotics.9 Because gingipain production helps the organism thrive, directly targeting it may impact the livelihood of P. gingivalis. Orally administered gingipain inhibitors protect against brain cell death and clear P. gingivalis from the brain.9 Trials on this approach are ongoing. If this approach is successful, future research might show that treating periodontitis in the initial stages could affect the development or progression of AD.11

In patients who have a family history of AD, treating periodontitis at the earliest stages should be a priority. If a patient previously completed genetic testing for AD and is positive, periodontal treatment and maintenance should be emphasized to reduce the spread of organisms within the body. Control of biofilm growth and maturation can be established through periodontal maintenance every 90 days as well as daily oral care aimed at removing both supragingival and subgingival biofilm. Dental hygienists are charged with educating patients about the connection of these organisms and AD.

Conclusion

Dental hygienists are capable of observing behavioral signs related to AD in their patients. Patients exhibiting AD-related symptoms should be referred to their primary care physician. Additionally, the presence of periodontitis should be evaluated closely and treated early.

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. What IS Dementia? Available at: alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia. Accessed August 12, 2022.

- Freedman V, Cornman J, Kasper J. National health and aging trends study trends chart book: key trends, measures and detailed tables. Available at: micda.isr.umich.edu/wp-content/uploads/떖/葏/NHATS-Companion-Chartbook-to-Trends-Dashboards-2020.pdf. Accessed August 12, 2022.

- Rajan K, Weuve J, Barnes L, McAninch E, Wilson R, Evans D. Population estimate of people with clinical AD and mild cognitive impairment in the United States (2020-2060). Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17:1966–1975.

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2022 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Available at: alz.org/media/Documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf. Accessed August 12, 2022.

- Abbayya K, Puthanakar N, Naduwinmani S, Chidambar Y. Association between periodontitis and alzheimer’s disease. N Am J Med Sci. 2015;7:241–246.

- National Institute on Aging. How Alzheimer’s Changes the Brain. Available at: nia.nih.gov/health/video-how-alzheimers-changes-brain. Accessed August 12, 2022.

- Chen CK, Wu YT, Chang YC. Association between chronic periodontitis and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a retrospective, population-based, matched-cohort study. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017;9:56.

- Alzheimer’s Association. Causes and Risk Factors for Alzheimer’s Disease. Available at: alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers/causes-and-risk-factors. Accessed August 12, 2022.

- Dominy S, Lynch C, Ermini F, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci Adv. 2019;5:eaau3333.

- The National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Periodontal Disease in Adults (Age 30 or Older). Available at: nidcr.nih.gov/research/data-statistics/periodontal-disease/adults. Accessed August 12, 2022.

- Ryder M. Porphyromonas gingivalis and Alzheimer disease: Recent findings and potential therapies. J Periodontol. 2020;91(Suppl 1):S45-–49.

- Positive Approach to Care. About Dementia. Available at: teepasnow.com/about-dementia. Accessed August 12, 2022.

- Snow T. Workshop A: normal aging vs not normal aging. Available at: learn.teepasnow.com/trainer-post-certification-tools. Accessed August 12, 2022.

- Mendez MF. Degenerative dementias: Alterations of emotions and mood disorders. Handb Clin Neurol. 2021;183:261–281.

- Gonzalez Cademartori M, Torres Gastal M, Giacommelli Nascimento G, Fernando Demarco F, Britto Correa M. Is depression associated with oral health outcomes in adults and elders? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Invest. 2018;22:2685–2702.

- Positive Approach to Care. The GEMS: Brain Change Model. Available at: teepasnow.com/about/about-teepa-snow/the-gems-brain-change-model. Accessed August 12, 2022.

- Schneider J, Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans S, Bennet D. The neuropathology of probable alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:200–208.

- Cassels C. FDA Clears diagnostic test for early Alzheimer’s. Available at: medscape.com/viewarticle/덋#:~:text=The%20US%20Food%20and%20Drug,of%20Alzheimer’s%20disease%20(AD). Accessed August 12, 2022.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2022; 20(9)38-41.