KLUBOVY/VETTA/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

KLUBOVY/VETTA/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Guide to Treating Adolescent Patients with Major Depressive Disorder

Oral health professionals can play a key role in serving this patient population.

This course was published in the February 2021 issue and expires February 2024. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define major depressive disorder (MDD) and its effects on daily activities.

- Discuss a comprehensive oral care plan for adolescent patients with MDD.

- Explain cognitive behavior therapy techniques to support adolescent patients with MDD.

Adolescence is shaped by biological, cognitive, and social processes. Healthy adolescent development is characterized by an increased self-awareness, satisfaction, growth, and resilience. Adolescence represents a critical phase in exploration and risk-taking behaviors, formation of peer relationships, changes in family relationships, and development of identity and self-direction. Stress, hormones, unlearned resilience, and other challenges are why adolescents are more vulnerable to depression and anxiety.1

Depression is one of the leading causes of illness and disability among adolescents worldwide. In 2017, the National Institute of Mental Health reported that 3.2 million adolescents between the ages of 12 and 17 had experienced at least one major depressive episode.2 Girls were more likely to experience such an episode (20%) compared with boys (6.8%); rates were also higher among those of mixed race/ethnicity (16.9%). Major depressive disorder (MDD) affects all aspects of an adolescent’s life including diet, exercise, and oral hygiene habits.3–6

Well-trained and empathetic oral health professionals are able to provide high-quality dental care to this population. A trusting patient-provider relationship is necessary for patient compliance with self-care and adherence to regular dental visits.6 The purpose of this article is to understand the complexity of adolescent depression, its effect on oral health, and the key role oral health professionals can play in serving this patient population.

WHAT IS MAJOR DEPRESSIVE DISORDER?

MDD is the presence of five or more of the following symptoms during a 2-week period along with either a depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure:7

- Significant weight loss or weight gain

- Insomnia or hypersomnia

- Psychomotor agitation or retardation

- Feelings of worthlessness or guilt

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Inability to think or concentrate, indecisiveness

- Thoughts of death or suicide ideation

Common symptoms of MDD significantly impact school, family, and social relationships, making daily activities difficult.8 MDD is associated with difficulties in processing negative information, leading to the rumination of negative mood states.9 Inhibitory processes and deficits of MDD include the inability of patients to control and stabilize negative moods with positive and rewarding stimuli.9,10 Adolescents with MDD also experience feelings of hopelessness, boredom, and changes in sleeping patterns.11

Common risk factors for MDD include a family history of depression, trauma, abuse, or neglect; parental conflict, inadequate peer relationships; poor academic performance; substance use/abuse; negative thinking; and deficit in coping skills.8,11 No specific gene has been identified in relation to MDD; however, research has shown that genomic biomarkers can help identify patients more susceptible to depression. Additionally, low levels of three major neurotransmitters:—dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin—have all been linked to MDD diagnosis.12

SCREENING FOR DEPRESSION IN THE OPERATORY

Although there is limited research on the effectiveness of depression screening by oral health professionals, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that primary care physicians screen for depression among adolescents ages 12 to 18.8 Oral health professionals are in a unique position to screen adolescents for depression because preventive dental visits often occur twice a year, and even more frequently when the patient is undergoing orthodontic treatment.

Dental hygienists spend the most one-on-one time with patients; this opportunity can create a genuine and empathetic patient-provider relationship. Additionally, developing an ongoing interprofessional relationship with the patient’s pediatrician and mental health provider is extremely important when caring for patients with MDD.5,8 Evidence suggests depressive symptoms and social functioning improve after screened adolescents receive treatment.8

Depression screening tools in the adolescent population can be used effectively in the dental office.8 The USPSTF recommends depression screenings for all adolescents but those at higher risk for MDD can be identified through common risk factors. A comprehensive patient history allows the dental team to identify risk factors such as sociodemographic factors (age, gender, race/ethnicity, low socioeconomic status, public insurance coverage).8,11 Depression is more likely to be a comorbid condition when a patient has other chronic medical conditions. As such, the initial health history interview is critical in providing quality care and treating the whole patient.5–7

Multiple depression screenings are available. The two most commonly used for adolescents are the Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents (PHQ-A) and the primary care version of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).8 The PHQ-A provides a scoring system and the BDI is self-scored. Research supports the use of oral responses as opposed to written ones when using these assessments.13

The PHQ-A is an adolescent modified version of the PHQ-9, a nine-question depression scale.14 The PHQ-A is free, quick, self-administered, and easy to use.15,16 The inclusion of a question about suicidal thoughts or ideations is a powerful instrument to assess for feelings of hopelessness, a generally recognized symptom of MDD.17 Johnson et al15 reported that adolescents with a PHQ-A diagnosis expressed significantly impaired mental functioning, more physical pain and poorer overall health compared to those without an MDD diagnosis.

ORAL HEALTH IMPLICATIONS OF ADOLESCENT DEPRESSION

Additional circumstances may suggest a referral to the patient’s pediatrician is needed. These include extreme fear of dental treatment; sleep bruxism and/or temporomandibular joint pain; extensive decayed, missing, or abfracted teeth; presence of chronic medical condition; unexplained dissatisfaction with the appearance of teeth; intermittent pain of unknown origin; or poor oral hygiene inconsistent with overall appearance.5 Additional symptoms include poor diet, physical inactivity, obesity, smoking, poor oral health, sleep, and vitamin D deficiency.3,4

Mental health is directly related to oral health status and outcomes; this is especially true for adolescents who are learning to assess and manage physiological, emotional, and social changes.1,4,11 Adolescents with MDD are at increased risk for oral health problems as a result of poor oral hygiene; unhealthy eating habits including the consumption of sugary drinks and a carbohydrate-rich diet; and comorbid conditions such as substance misuse (tobacco, alcohol, or psychostimulants), emotional stress, and trauma.4,5,8,11

Maida et al18 conducted a focus group of adolescent perceptions and attitudes of oral health including self-image and the effect on social relationships. The study also discussed adolescent views on self-care and their role in good oral health outcomes. Adolescent beliefs and attitudes toward oral health are viewed in terms of social interaction, friendships, personal appearance, and valued as important for their chances of getting a good job and succeeding in life. Unfortunately, adolescents with MDD are self-critical, have increased negative cognition, and difficulty changing these damaging behaviors.9,10

Gungormus and Erciyas19 found an association between bruxism and higher levels of self-reported anxiety and/or depression, especially among patients with temporomandibular disorder. While bruxism is more common in patients with depression and/or anxiety, antidepressants (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, such as fluoxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine, often cause bruxism and jaw pain.20 Patients experiencing these adverse effects from antidepressant therapy may be treated with a substitute medication, such as buspirone, or dose reduction and/or cessation of antidepressant medication may be considered with alternate psychotherapy.20 Antidepressant medications also affect salivary flow in patients, raising risk of xerostomia and caries.4,5

Additionally, adolescents with depression are at an increased risk of developing poor periodontal health. This relationship is based on biological (host immune response and inflammation) and behavioral factors (poor oral hygiene, diet, and exercise).3,5,6 Many psychosocial factors (loneliness, shame, embarrassment, isolation) are related to poor oral hygiene, which increase the risk of periodontal diseases. Ramesh et al21 concluded that depression may be a risk factor in the development and progression of aggressive periodontal diseases. Researchers suggest that stress and depression may modify the host immune response, which, in turn, can increase vulnerability to periodontal diseases.3,21 Further, individuals who experience depression and stress may have elevated inflammatory markers while treatment with antidepressants—particularly SSRIs—decrease the production of pro-inflammatory cytokine—such as tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1—potentially affecting periodontal tissues.3 A study by Okoro et al22 found that adults with depression were less likely to seek oral healthcare and more likely to experience tooth loss. Therefore, oral health professionals must work closely with adolescents who present with depression or symptoms of depression and create a plan for addressing their periodontal health.

A clinical guide for treating adolescent patients with MDD should include the following:4-6

- Know the main symptoms of MDD and the common medications used to treat it as well as side effects of these medications, including interactions with local anesthetic.

- Obtain a complete medical history including past and present mental health conditions, medications, and physician name and contact information.

- Consult with other healthcare professionals as part of a comprehensive care team to identify patients who might need special management (eg, mental health referral).

- Be empathetic, respectful, and nonjudgmental of the patient’s mental health condition. Understand that the patient may make oral hygiene improvements and then relapse because of a depressive episode and regress to poor oral health.

- Keep appointments short and be consistent and predictable, and use positive reinforcement. Be flexible and willing to adapt, allow the patient autonomy to choose how much can be accomplished at any one appointment, and attempt more each time.

- Complete the initial intake and assessment of the patients’ dental health needs; assign treatment providers; begin with simple procedures first (eg, exam, X-rays, and prophylaxis); and help the patient and family learn about good oral health habits, the side effects of antidepressant medications, and the impact diet has on oral health and overall health (nutritional counseling).

- Allow for more frequent continuing care visits can help reinforce oral health behaviors and monitor the progression of oral diseases.

- Help the patient set realistic and achievable oral health goals, and encourage and monitor improvements and challenges.

- Use caution when recommending or prescribing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or analgesics, such as hydrocodone, oxycodone, or tramadol, because of the increased risk of self-harm and the interaction with antidepressants.

COGNITIVE-BEHAVIORAL TECHNIQUES IN THE DENTAL SETTING

Besides consulting with the patient’s medical management team, oral health professionals can apply techniques to reduce MDD-associated dental anxiety. This professional guidance can help to change dysfunctional thoughts and behaviors associated with MDD.9,10 Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and motivational interviewing (MI) are appropriate techniques for use in the dental setting. CBT is a type of psychotherapy used to improve functioning and quality of life for adolescents with MDD. Oral health professionals are well versed in MI as it is often used to improve oral health habits; however, CBT, which improves self-control, perceptions of self-worth, social skills, problem-solving skills, and reduction of dysphoria, may not be as familiar.10

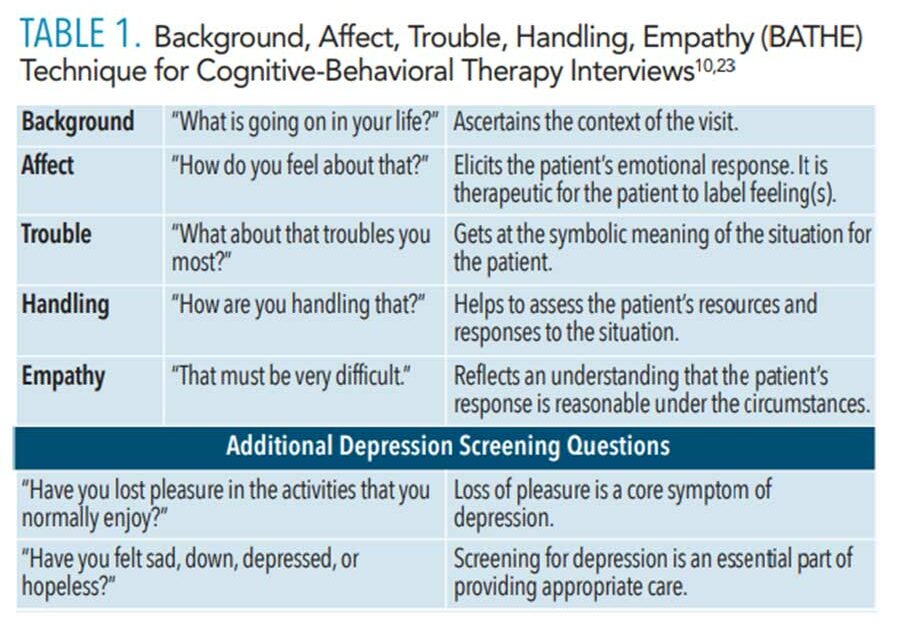

Clabby10 introduced a menu of CBT techniques for use in busy settings such as dental hygiene appointments. For example, the BATHE (background, affect, trouble, handle, empathy) technique used during the initial interview allows oral health professionals to assess adolescent patients for depression, anxiety, or stress disorders (Table 1). Similar to SOAP (subjective, objective, assessment, plan), this quick assessment guide works well for identifying illnesses and managing treatments, and is used as the standard for medical documentation.23,24 BATHE encourages adolescents to share their perceptions, feelings, concerns, and solutions for a troubled situation. Oral health professionals’ empathetic response needs to acknowledge the patient’s feelings and concerns and direct the conversation toward coping strategies, allowing the patient to enhance his or her ability to control the troubled situation. This approach is quick and effective at empowering patients to trust themselves while strengthening the patient-provider relationship.10,23,24 Lieberman24 suggests the addition of two more questions following the BATHE method to provide an effective and rapid screening for depression (Table 1). The recognition of depressive symptoms can minimize the percentage of adolescents with depression who are undiagnosed or misdiagnosed.6,25

Clabby10 introduced a menu of CBT techniques for use in busy settings such as dental hygiene appointments. For example, the BATHE (background, affect, trouble, handle, empathy) technique used during the initial interview allows oral health professionals to assess adolescent patients for depression, anxiety, or stress disorders (Table 1). Similar to SOAP (subjective, objective, assessment, plan), this quick assessment guide works well for identifying illnesses and managing treatments, and is used as the standard for medical documentation.23,24 BATHE encourages adolescents to share their perceptions, feelings, concerns, and solutions for a troubled situation. Oral health professionals’ empathetic response needs to acknowledge the patient’s feelings and concerns and direct the conversation toward coping strategies, allowing the patient to enhance his or her ability to control the troubled situation. This approach is quick and effective at empowering patients to trust themselves while strengthening the patient-provider relationship.10,23,24 Lieberman24 suggests the addition of two more questions following the BATHE method to provide an effective and rapid screening for depression (Table 1). The recognition of depressive symptoms can minimize the percentage of adolescents with depression who are undiagnosed or misdiagnosed.6,25

Clabby10 also described the CARL (change it, accept it, reframe it, or leave it) technique as a successful intervention for adolescents with MDD (Table 2). This technique allows adolescents to recognize and reflect on their past decisions, as well as empowers them to think about available options for difficult circumstances. CARL helps adolescents with MDD reduce feelings of helplessness by understanding the four choices they have in every situation. The foundation of these strategies is patient-provider communication and rapport. CBT is an ideal modality for adolescents with MDD because it connects coping skills to specific actions.10 The prepared oral health professional can recognize adolescent depression risk factors and symptoms, subsequently introducing family support and community resources to form a collaborative care team. Working collaboratively, oral health professionals can be part of interprofessional teams to support adolescents experiencing MDD.

![CARL Tecjnique]() CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

Oral health professionals who work with adolescents should be knowledgeable of the manifestation and appearance of depression among this population. Adolescents who exhibit depressive symptoms, behaviors, or risk factors should be screened for depression. Increased awareness of depressive symptoms and risk factors among adolescents is essential to screening, accurate diagnosis, and successful treatment. Acceptance and empathy are fundamental characteristics of oral health professionals who work with adolescents with MDD. Early intervention and treatment of MDD can lead to positive health and behavioral health outcomes including increased motivation to perform daily oral self-care tasks. Oral health professionals need to understand the complexity of adolescent depression, its effect on oral health, and the key role they can play in serving this patient population.

REFERENCES

- The Promise of Adolescence: Realizing Opportunity for All Youth. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2019.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Major Depression. Available at: nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.shtml. Accessed January 21, 2021.

- Berk M, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, et al. So depression is an inflammatory disease, but where does the inflammation come from? BMC Med. 2013;11:200

- Kisely S. No mental health without oral health. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;6:277–282.

- Hexem K, Ehlers R, Gluch J. Dental patients with major depressive disorder. Curr Oral Health Rep. 2014;1:153–160.

- Doyle PE, Longley AJ, Brown PS. Dental-mental connection. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2012;10(11):19–22.

- Desk Reference to the Diagnostic Criteria From DSM-5. Arlington, Virginia: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:94–95.

- Siu AL. Screening for depression in children and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:360–366.

- Kircanski K, Joormann J, Gotlib IH. Cognitive aspects of depression. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci. 2012;3:301–313.

- Clabby JF. Helping depressed adolescents: a menu of cognitive-behavioral procedures for primary care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;8:131–141.

- Clark MS, Jansen KL, Cloy JA. Treatment of childhood and adolescent depression. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:442–448.

- Saveanu RV, Nemeroff CB. Etiology of depression: genetic and environmental factors. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2012;35:51–71.

- Arroll B, Khin N, Kerse N. Screening for depression in primary care with two verbally asked questions: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2003;327:1144–1146.

- Maurer DM, Raymond TJ, Davis BN. Depression:screening and diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98:508–515.

- Johnson JG, Harris ES, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents: validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. J Adolescent Health. 2002;30:96–204.

- Kung S, Alarcon RD, Williams MD, et al. Comparing the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) depression measures in an integrated mood disorders practice. J Affect Disord. 2013;145:341–343.

- Parker GF. DSM-5 and psychotic and mood disorders. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2014;42:182–190.

- Maida CA, Marcus M, Hays RD, et al. Child and adolescent perceptions of oral health over the life course. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:2739–2751.

- Gungormus Z, Erciyas K. Evaluation of the relationship between anxiety and depression and bruxism. J Int Med Res. 2009;37:547–550.

- Garrett AR, Hawley JS. SSRI-associated bruxism. Neurol Clin Pract. 2018;8:135–141.

- Ramesh A, Malaiappan S, Prabhakar J. Relationship between clinical depression and the types of periodontitis—a cross-sectional study. Drug Invent Today. 2018;10:659–663.

- Okoro CA, Strine TW, Eke PI, Dhingra SS, Balluz LS. The association between depression and anxiety and use of oral health services and tooth loss. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012,40:134-144.

- Lieberman JA, Stuart MR. The BATHE method: incorporating counseling and psychotherapy into the everyday management of patients. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;1:35–38.

- Lieberman JA. Identifying depression in primary care. J Postgrad Med. 2003;114(5 Suppl):5–9.

- Saluja G, Iachan R, Scheidt PC, Overpeck MD, Sun W, Giedd JN. Prevalence of and risk factors for depressive symptoms among young adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:760–765.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. February 2021;19(2):32-35.