Common Eye Disorders Encountered in the Dental Office

How dental hygienists can reduce the incidence of these diseases by recognizing symptoms that lead to earlier detection and treatment.

This course was published in the March 2010 issue and expires March 2013. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify four common eye disorders encountered by dental hygienists.

- Discuss the importance of early intervention in eye disorders.

- Identify the different types of eye injuries that can occur in the dental setting.

- Discuss appropriate eye protection for both patients and dental team members.

Healthy vision and good eye sight are important to everyone from infancy onward. Diseases, accidents, infections, and age endanger our vision and can sometimes lead to blindness. Many ocular ailments have symptoms that occur very gradually and painlessly but may result in complete loss of function. Dental hygienists and the entire dental team hold value in the function and protection of teeth; the same value should be applied to the eyes and emphasized through patient care and education. Many eye disorders are secondary to other diseases that also threaten oral health, such as diabetes mellitus. These diseases require dental hygienists to be acutely aware of early signs and symptomatic indicators. This same disease detection should be applied to common eye disorders to help prevent further disease progression and possible loss of sight.

CATARACTS

Cataracts are one of the most common, treatable causes of blindness in the world.1 By age 65, 90% of people in the United States will have experienced a cataract.1,2 Cataracts affect the lens of the eye, which is transparent and allows light to pass through and transmit images to the retina.1 The retina receives, processes, and sends the images to the brain, which produces sight. New cells are continuously being made in the lens of the eye, however, numerous aging factors cause portions of the lens to become hardened, dense, and cloudy. The lens is no longer able to transmit clear images to the retina when it is cloudy and hard. The majority of cataracts are attributed to the aging process and exhibit very few symptoms. Cataracts grow slowly and may take several years to affect vision.

The different types of cataracts are:

- Age-related cataracts. They are the most common and have a subclassification based on their location (nuclear, cortical, and post-subcapsular).

- Secondary cataracts. They are caused by medications such as corticosteroids or diseases such as diabetes. These cataracts are more prevalent among people who have diabetes.

Traumatic cataracts. These result from injury or trauma to the eye(s).

- Congenital cataracts. These are rare and detected at birth or in the first year of life.

People who have cataracts may experience the following symptoms: blurred-cloudy vision, double vision, sensitivity to light, or a constant glare in the path of vision (Figure 1).1-2 Colors may appear washed out and frequent changes may be needed to prescription eyeglasses. An optometrist or ophthalmologist diagnoses a cataract by performing a visual acuity test, looking through a slit-lamp during a dilated eye examination, or by looking through an ophthalmoscope. Once a cataract is diagnosed, it is treated if quality of life is compromised.1

Surgery is the only treatment for cataracts and includes lens removal and replacement. This is one of the most successful surgical procedures performed on the eyes and is an outpatient surgery conducted under local anesthesia. If both eyes require surgery, usually only one eye is treated at a time. The other eye may be treated a few weeks to a month after the original surgery, thus allowing adequate healing of the first eye.1

Although, there is no exact prevention method, protection from ultraviolet B (UVB) light may prevent or slow the progression of cataracts.1,3 An important preventive measure for any eye disorder is to take care of other health problems and chronic diseases.1-3 Free radicals from cigarettes increase the rate of cataract formation, therefore, smoking is discouraged especially if a cataract has been detected. Environments with second-hand smoke should also be avoided. If a cataract exists but surgery is not yet appropriate, contacts and glasses should have a current and accurate prescription. While waiting, the use of a magnifying glass and brighter lamps that accommodate halogen lights or 100-watt to 150-watt incandescent bulbs may be helpful. Night driving is discouraged for anyone who has cataracts.3

GLAUCOMA

Glaucoma is a leading cause of blindness across the world, especially among older people.4 With glaucoma, early detection and treatment are vital to preventing vision loss. Glaucoma is a group of eye disorders that cause optic nerve damage due to increased eye pressure. Delicate nerve fibers of the optic nerve transmit images to the brain, which allow for clear vision. When these fibers are damaged due to increased pressure, blind spots develop in the field of vision and tunnel vision is experienced (Figure 2). Resulting nerve damage and vision loss are permanent. Most people detect signs of glaucoma very late in the disease process after severe optic nerve damage has occurred. Blindness is experienced when the entire optic nerve has been damaged.

The etiology of glaucoma is not fully understood due to the pathophysiology of numerous different types of glaucoma.1,4 Pressure in the eye is created by mechanical compression and decreased blood flow to the optic nerve. Glaucoma may occur in high-tension or low-tension environments. It can be congenital or acquired and can be further subclassified into open-angle (most common) and angle-closure types, depending on the mechanism that reduces aqueous flow and creates pressure in the eye. In open-angle glaucoma, the open drainage angle of the eye becomes blocked by cells, tissue, or particles and leads to increased eye pressure. Optic nerve damage occurs over a slow, painless period and results in vision loss. In angle-closure glaucoma, the drainage angle becomes blocked from the iris pushing or pulling over the area. Acute symptoms, such as loss of vision in one eye, severe eye pain, blurred vision, flashes of light, and halos around light, must be treated immediately.4 Other types of glaucoma may be caused by injuries, tumors, and other eye diseases.

Symptoms that indicate a need for a thorough eye examination include: unusual trouble adjusting to dark rooms, challenges focusing on near or far objects, squinting or blinking due to unusual light, iris color change, encrusted or swollen lids, double vision, excessive tearing, dry eyes, and the appearance of ghost-like images. Diagnosis of glaucoma is determined using tonometry (measurement of the eye pressure), gonioscopy (inspects the drainage angle of the eye), opthalmolscopy (evaluates the health of the optic nerve), and perimetry (measures and tests the visual field of each eye). Like periodontal diseases and diabetes, glaucoma cannot be cured but it can be effectively managed.2,4 Treatment modalities for glaucoma help to prevent further damage to the optic nerve. Oral medications are commonly combined with eye drops to alter the circulation of eye fluid and reduce eye pressure. Laser and surgical operations are also treatment options.1,4

Risk factors for glaucoma include elevated eye pressure, age, African ethnicity, familial history, and nearsightedness. Patients who have glaucoma should understand the importance of monitoring exams to evaluate treatment and track progression of the disease. Lifestyle changes include sipping fluids slowly and carefully monitoring intense exercise routines because these both contribute to increased eye pressure.

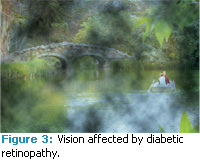

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a complication of diabetes mellitus that causes damage to the circulatory system of the retina.4 When damaged, blood vessels within the retina leak blood, grow fragile branches, and produce scar tissue. Blurred images are then created and sent to the brain from the retina (Figure 3). Bleeding vessels can lead to macular edema (retinal swelling), which is the leading cause of permanent vision loss among people who have diabetes.4,5 Blood and fluid leak from the vessels allowing fatty material to deposit in the retina, causing it to become swollen. It is possible to see the early signs of this disorder before damage occurs, vision blurs, or blindness results. DR may also cause abnormal blood vessels to grow on the retinal surface, termed proliferative retinopathy.4 This abnormal growth causes glaucoma and may pull the retina away from the back of the eye, leading to severe vision loss including blindness.

The longer someone has diabetes, the higher his or her risk becomes for developing DR.5 People who have diabetes should look for the onset of symptoms in their early stages, which include: difficulty reading, blurred vision, seeing rings around lights, dark spots or flashing lights, and loss of vision in one eye. Treatment is not required for mild cases, but close monitoring of blood sugar and blood pressure levels is crucial to prevent progression of DR.4,5 Advanced cases attempt to stop damage leading to vision loss and include: laser surgery, intraocular steroid injections, cryotherapy (freezing), and vitrectomy (operative).5

MACULAR DEGENERATION

Macular degeneration (MD) affects 1.5 million Americans and is the leading cause of visual impairment in people older than 65 years of age.4 The exact cause is unknown, but the condition develops as the eyes age. MD is characterized by a breakdown of the macula (central part of the retina) of the eye. Close work, such as threading a needle, becomes difficult because blurriness and blind spots develop in the central part of vision (Figure 4). By itself, MD does not cause blindness and is very case dependent; it develops differently in each person with varying symptoms that may include progressive loss of central vision.1,4

There are two main categories of macular degeneration: dry (most common) and wet type (more damaging).1,4 The dry type develops when the delicate macula tissue becomes thinned and does not function properly, sometimes developing into the wet type. Growth of abnormal blood vessels behind the macula that hemorrhage and form scar tissue if untreated characterize the wet type. Treatment includes medications, laser treatments, and photodynamic therapy.4 The National Eye Institute recommends a diet rich in green leafy vegetables, Omega-3 fatty acids, egg yolks, and fish. Supplements that may help prevent MD include antioxidants, zinc, and vitamins A, C, D, and E.6

EYE PROTECTION FOR PATIENTS AND DENTAL TEAM MEMBERS

Preservation of eye sight and proper eye protection are important for both patients and dental team members.7 Patients who have common eye disorders must have confidence that dental providers will protect their eyes and reduce any threat of disease progression. All patients and dental team members should wear eye protection upon entering the operatory. Modern dental instrumentation and techniques create an increased ocular threat to patients and dental team members.8

Eye injuries in the dental office occur among both patients and dental team members, including ocular contusions from sharp instruments and rubber dam clamps, conjunctivitis linked to waterline contaminants, and three cases of in-office injury that resulted in the complete loss of an eye.9-12 Ocular injuries in the dental office often go unreported due to the localized impact of trauma, low incidence of complete blindness, and the litigious status of current society.8

Dental hygienists must be aware of the various types of ocular threats in the dental setting that may result in loss of quality of life, production, and revenue. They include: mechanical trauma (most common), chemical insult, microbial infections, and electromagnetic radiation.8,11 Mechanical trauma may result from instrumentation transfer or particles projected by dental handpieces, which produce a velocity of up to 50 mph.8 Chemical insult includes injury from dental materials and medications. Microbial infections can result from contaminated bioaerosols generated by handpiece cooling mists and ultrasonic/air polishing units, which may contain bacteria, viruses, fungi, and prions.8-11

Electromagnetic radiation is also a potential threat to ocular health. The adoption of laser usage in dentistry is increasing annually throughout the United States.13 As a result, eye injuries caused by lasers are likewise on the rise. Approximately 35 injuries are reported every year, yet more may occur and go unreported.14

Laser energy is scattered, reflected, absorbed, or transmitted. Therefore, eye protection is mandated for both patients and dental team members.15 Warning signs should be placed in a visible area outside of the treatment room where the laser is used, much like radiation signage. Goggles should be worn by the patient and dental team, and must be specific to the wavelength of the laser being used. The lens color and density of the eye protection depends on the laser being used because one type of protection will not cover the full range of wavelengths used in the dental setting. Additionally, eye protection surfaces should be maintained carefully to avoid scratching or wearing away of the protective coating. Extreme care should be exercised if using any optic instruments, such as magnifying glasses, loupes, microscopes, cameras, or videos, because they can magnify the image energy on the eye and transmit it. Any reflective surfaces should be used with extra caution.16

Damage to the eye can lead to headaches, excessive watering of the eyes, and floaters (distortions caused by dead cells that detach and float in the vitreous humor.) Cataracts and retinal damage can occur as well as retinal damage that results in partial loss of vision or complete blindness.17 Damage to the cornea and lens can occur along with blind spots in the fovea (scotoma). Lasers can also generate a plume containing contaminants that are irritating to the eye.

As with lasers, curing lights can be damaging as well.18 So a protective shield or eye wear should be used to filter to the emitted UV rays.

Safety protocols must be adhered to in order to avoid permanent damage to the eyes. The eyes are the most important sense to the practice of dentistry. And, since vision provides more than 75% of all sensory information, every factor that affects vision should be given ample and immediate attention. Although many hazards exist in the dental setting, fortunately, most eye injuries can be prevented through use of protective measures. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has regulations currently in place to reduce potential ocular threats among employees in the dental setting. Dental hygienists should be aware of these laws and promote compliancy among all team members.

THE FUTURE

Dental hygienists play a valuable role in reducing the rates of common eye disorders and injuries by detecting links between ocular and primary disease patterns, emphasizing the need for eye examinations, and providing optimal eye safety in the dental setting. Dental hygienists should inform their patients about numerous resources for common eye disorder support from the American Academy of Ophthalmology, American Academy of Optometry, and the National Retina Institute.

REFERENCES

- Kanski JJ. Lens: acquired cataract. In: Clinical Ophthalmology: A Systematic Approach. 6th ed. Edinburgh, UK: Elsevier Butterworth-Keinemann; 2007:337-367.

- Klein BE, Klein R, Lee KE. Diabetes, cardiovascular disease, selected cardiovascular disease risk factors, and the 5-year incidence of agerelated cataract and progression of lens opacities:The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126:782-786.

- The Mayo Clinic. Cataracts. Available at: www.mayoclinic.com/health/cataracts/DS00050. Accessed February 25, 2010.

- Yanoff M. Glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, macular degeneration. In: Ocular Pathology. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2009: 423-436, 602-618, 627-658.

- Klein R, Sharrett AR, Klein BE, et al. The association of atherosclerosis, vascular risk factors, and retinopathy in adults with diabetes: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1225-1229.

- Coleman H, Chew E. Nutritional supple mentation in age-related macular degenera tion. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2007;18:220-223.

- OSHA Standards. Eye and face protection 1910.132. Available at: www.osha.gov/SLTC/etools/eyeandface/pdf/eyeandfaceprotectionosharequirements.pdf. Accessed February 26, 2010.

- Bezan D, Bezan K. Prevention of eye injuries in the dental office. J Am Optom Assoc.1988;59: 929-934.

- Hales R. Ocular injuries sustained in the dental office. Am J Ophthalmol. 1970;70:221-223.

- Hartley JL. Eye and facial injuries resulting from dental procedures. Dent Clin North Am. 1978;22:505-515.

- Christensen RP. Maintaining infection controlduring restorative procedures. Dent Clin North Am. 1993;37:301-327.

- Barbeau J. Lawsuit against a dentist related to serious ocular infection possibly linked to water from a dental handpiece. J Can Dent Assoc. 2007;73:618-622.\

- United States Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 29 CFR Part 1910; Occupational exposure to blood-borne pathogens. Available at: www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=PREAMBLES&p_id=801. Accessed February 26, 2010.

- Sliney, D. Laser bioeffects. In: LIA Guide for the Selection of Laser Eye Protection. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2007:3-6.

- McNeil S, Powers J, Sverdrup L. Laser accident case histories. In: CLSO’S Best Practices in Laser Safety. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2008:155-172.

- Amitzia A, Chan R, Janssen B, Schoep D. Protective equipment. In: CLSO’S Best Practices in Laser Safety. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2008:23-40.

- Barat K. Laser safety management. In: Optical Science and Engineering. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 2006:2-11.

- Parker S. Laser regulation and safety in general dental practice. Br Dent J. 2007;202:523-532.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2010; 8(3): 48-51.

thank you. Is there an update on the subject of eye safety

Hisham