Addressing Cervical Class V Lesions

What dental hygienists need to know about the causes of these lesions and possible treatments in order to provide the most comprehensive care to their patients.

This course was published in the March 2010 issue and expires March 2013. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Understand the possible etiologic factors of carious lesions and noncarious cervical lesions occurring on the cervical third of the dentition.

- Discuss the treatment options for carious lesions and noncarious cervical lesions occurring on the cervical third of the dentition.

- Discuss combined periodontal and restorative therapy for treatment of cervical class V lesions that result in loss of the facial cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) with concomitant loss of root structure adjacent to the level of the CEJ.

Cervical class V lesions are not uncommon among adults and they can cause a loss of tooth structure in the cervical third of the facial aspect of the dentition.1 Typically crescent shaped, these lesions may be classified as carious or noncarious class V. If noncarious, the lesions have been referred to as abfractions, abrasions, or erosions,2 and they are attributed to toothbrush/toothpaste abrasion, occlusion, intrinsic and extrinsic chemical erosion, or a combination of these factors. In fact, it is likely that most noncarious cervical lesions (NCCLs) are mixed lesions. Carious cervical lesions are indicative of a patient with high caries risk. Treatment must include a customized prevention protocol including dietary and self-care counseling as well as a carefully directed fluoride regimen. These patients may also require salivary stimulants or replacements if xerostomia or reduction of the salivary flow is detected. Understanding the possible etiologic factors and treatment options for carious lesions and NCCLs that occur on the cervical third of the dentition is important for dental hygienists because of their role on the front line of prevention.

DESCRIPTION

Class V lesions may be present with soft carious dentin or a hard surface of sclerotic dentin. NCCLs may be shallow or deep, sensitive or not, and rapidly progressing or arrested. In all cases, the destruction of the tooth begins in the cervical third of the anatomical crown on an approximal surface, and extends apically onto the facial or buccal root surface. As a result, the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) on the facial or buccal aspect of the tooth is partially or completely obliterated. In some circumstances, loss of the CEJ may give the impression of significant gingival recession.

ETIOLOGY

Carious class V cervical lesions are the result of chronic plaque accumulation at the cervical third of the tooth in conjunction with a significant intake of fermentable carbohydrates. An additional risk factor is reduction in salivary flow and salivary quality due to xerostomia.3

NCCLs typically present as concavities on the facial aspects of teeth. Although they may present on an isolated tooth, NCCLs more commonly occur on several teeth in the same quadrant. These lesions are attributed to a varying combination of occlusal stress, toothbrush/toothpaste abrasion, and chemical erosion.

The term abfraction refers to an NCCL with an etiology that includes tooth flexion and occlusal stress.4 When a tooth is exposed to lateral or oblique forces, the tooth will bend slightly near the CEJ. This flexion creates micro-fractures of thin enamel and subsequent exposure of the underlying dentin, which is then susceptible to mechanical and/or chemical wear. Parafunctional habits, ie, tooth grinding and/or clenching, may be the source of these destructive occlusal forces. A correlation between wear facets on the occlusal aspects of the dentition and NCCLs has been reported.5

A recent in vitro study provides an alternative explanation for the development of abfractions.6 In the study, extracted teeth were mechanically brushed at the cervical third with and without toothpaste. Abfraction- like lesions resulted in the teeth that received the toothbrushing with toothpaste. The investigators concluded that the abrasive properties in toothpaste can wear away enamel at the cervical third and the underlying dentin. The study also evaluated the process of gingival abrasion, which resulted in the loss of synthetic periodontal tissues adjacent to the developing cavity on the extracted teeth. In time, the cavity created in this in vitro study began to extend apically onto the newly exposed root surface. Eventually, a crescent-shaped loss in tooth structure appeared with a polished hard surface. The lesion created by this process presented with an obliteration of part or the entire CEJ on the facial aspect of the test teeth.6

Improper toothbrushing technique, rough and hard toothbrush bristles, and abrasive toothpastes probably all contribute to the progression of NCCLs. Another theory suggests that brushing immediately after consuming an acidic meal may result in more cervical wear than if brushing was held off for 30 minutes.7 The worst time to brush teeth may be when the surfaces are the softest and most vulnerable to mechanical wear. Waiting 30 minutes allows normal saliva to remineralize the acid-affected teeth.

Another possible factor in the development of NCCLs is chemical erosion.8 The most dramatic examples of tooth erosion are found among patients who have bulimia. These patients frequently expose their tooth surfaces to concentrated digestive acids during the selfforced act of regurgitation. A more common factor is the increased consumption of soft drinks and sports drinks, which have a low pH. Sports drinks are usually sipped during exercise when the individual is dehydrated. The state of dehydration results in less salivary buffering.

RESTORATIVE TREATMENT OPTIONS

Therapy for class V carious lesions should always include both prevention strategies and the excavation of all infected dentin. Composite resin is frequently used to restore these teeth because of its impressive esthetic capabilities, its conservative preparation requirements, and its relative ease of use.9 The disadvantage to using composite resin is its disappointing record of root-surface marginal leakage and secondary caries. Its use also requires adequate isolation and contamination control. Composite resin is a good choice for abrasion and erosion lesions. An interesting option for abfraction lesions is the use of flowable or microfilled composites, which are slightly more flexible than conventional hybrid composites. The rational for using a flexible material is that the composites will bend with the tooth and lower the risk of marginal seal breakdown and/or dislodgement.

Although the use of amalgam is decreasing in general, it is still a viable restorative option for cervical caries in areas where isolation and access are difficult.10 Amalgam has some disadvantages such as poor esthetics and the need for additional preparation of the tooth structure in order to achieve undercuts for retention.

Perhaps one of the best restorative materials for restoring carious cervical lesions is glass ionomer.11 This material offers the slow release of fluoride, which creates a zone of caries inhibition around the restoration. Although it will not eliminate the possibility of secondary caries, this fluoride release makes the surrounding tooth structure less susceptible to caries formation. Glass ionomers also form a durable chemical bond to dentin and enamel. The most popular glass ionomers today are resin-modified glass ionomers, which are light curable and easier to use than conventional glass ionomers.12,13 Another option is the “sandwich technique” in which a layer of glass ionomer is placed first and then covered with a layer of harder, more esthetically pleasing composite.

PERIODONTAL THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS

The development of cervical class V lesions results in the exposure of dentin axial to the lost enamel. As the destructive process migrates apically to the obliterated CEJ, loss of gingival tissues and concomitant damage to the exposed root surface occur. The outcome is an elongated clinical crown with a gouge in the facial aspect of the tooth. The most coronal aspect of the lesion is the abrasion line. The most apical aspect of the lesion may be smooth or jagged.

One method of treating a cervical class V lesion is to cover the decontaminated and smoothed root surface with a soft tissue graft. Free gingival grafts are a predictable technique for root coverage when the interdental bone and soft tissues are intact.14 If the loss of interdental bone is not too severe, root coverage can still occur, although it is not as predictable.

The use of coronally advanced flaps for root coverage can also be successful and predictable in the presence of intact interdental tissues.15 Moreover, therapy involving a coronally advanced flap over an underlying connective tissue graft may also be successful.16 Increasing post-operative tissue thickness is the advantage of placing the flap over a connective tissue graft. Procedures involving coronally advanced flaps over barrier membranes and/or enamel matrix proteins may also be successful.17,18 These supplementary materials are used to facilitate guided tissue regeneration.

COMBINED PERIODONTAL/RESTORATIVE OPTION

If a lesion is treated with a restoration alone, the result is often a long tooth. If the lesion is treated with periodontal surgery alone, the result is typically a tooth that appears short. As the tooth-colored restoration requires minimal or no tooth preparation, significant odontolplasty may be warranted in order to achieve an esthetic and adherent outcome with a soft tissue graft procedure. One solution is to combine the restorative and the soft tissue graft options, which provides a more normal tooth length, a reduced need for dentinal bonding, and the re-establishment of the hard and soft tissue structure lost during the formation of the lesion.

Either therapy can be initiated first but the estimation of where the CEJ should be is key. If restorative therapy is started first, the restorative material is placed, restoring the damaged cervical aspect of the tooth. The restoration’s occlusal or incisal margin is the abrasion line (with a prepared bevel) and the gingival margin is the estimated location of the CEJ. Subsequently, the periodontal procedure for root coverage is performed. The goal of the second procedure is to establish a new and more coronal location for the free gingival margin.

A root coverage procedure can also be done first. In this scenario, the root is decontaminated and planed via odontoplasty with a diamond bur and curets. A root coverage procedure is then used, placing gingival tissue over the previously exposed dentin. The dental professional estimates where the CEJ should be and positions the gingival flap to that level. After a healing period, a toothcolored restorative material is placed to restore the remaining cervical lesion coronal to the new gingival margin.

Typically, if the loss of tooth structure is relatively deep, an advanced flap over a connective tissue graft will provide the necessary thickness of healed tissue, which results in esthetic improvement and also serves as a tissue barrier against possible future breakdown from inflammation due to bacterial plaque or traumatic toothbrush/ toothpaste abrasion.

If odontoplasty is necessary, a concern is that the removal of additional root structure could compromise the pulp. McGuire recommends that 3 mm in depth is the upper limit for attempting root coverage on a root surface with caries or on a previously restored root that has had the restoration removed.19

CASE REPORT

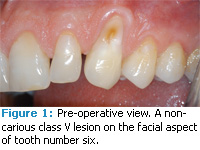

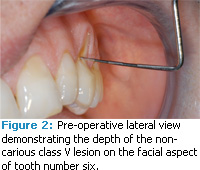

A 46-year-old man in good health presented with a noncarious class V lesion on the facial aspect of tooth number six. The patient’s chief concerns were the dentinal sensitivity associated with the exposed root structure and the esthetics of the area. Figure 1 shows a preoperative view of the lesion, which extended onto the root surface resulting in an occlusalapical length of 16 mm for the clinical crown. Normal crown length for a maxillary canine is 11 mm. Figure 2 demonstrates the 3 mm buccal-lingual depth of the lesion.

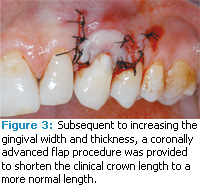

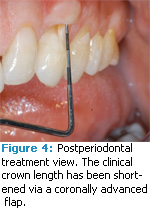

In order to increase the width and thickness of the gingival tissue, sliding pedicle flaps from the adjacent papilla were surgically positioned apical to the pre-operative mucogingival junction. Subsequent to a healing period of 3 months, an increase in thickness and width of attached gingiva was observed. In a second procedure, the increased zone of gingiva was advanced coronally 5 mm. This second procedure was performed to establish a new and more coronal level of the free gingival margin. Figure 3 shows the sutured advanced gingival flap. Figure 4 provides a post-operative view of the periodontal treatment. The free gingival margin is located at a more coronal position, resulting in a shorter clinical crown length. The new length is 11 mm and is the average length of maxillary canines. The surrounding gingival tissues probe no more than 1 mm.

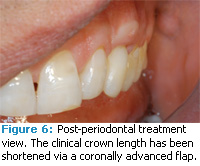

Figure 5 shows the area post-restorative therapy. A composite restoration was placed just slightly apical to the free gingival margin. Care was taken to smooth the most apical extent of the restoration and to not leave any flash of composite material. During the restorative procedure, a retraction cord was placed in order to access the subgingival area. The margin of the restoration is approximately 0.5 mm into the sulcus. Figure 6 provides a proximal view post-periodontal and post-restorative treatment. Normal contours of the periodontal tissues as well as the cervical third of the tooth have been established. The patient reported that sensitivity was eliminated and that he was satisfied with the esthetic outcome.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank Gene Petti, DDS, of West Roxbury, Mass, for the restorative therapy provided in the case report.

REFERENCES

- Levitch LC, Bader JD, Shugars DA, Heymann HO. Non-carious cervical lesions. J Dent. 1994; 22:195-207.

- Grippo JO. Abfractions: a new classification of hard tissue lesions of teeth. J Esthet Dent. 1991; 3:14-19.

- McComb D, Erickson RL, Maxymiw WG, Wood RE. A clinical comparison of glass ionomer, resinmodified glass ionomer and resin composite restorations in the treatment of cervical caries in xerostomic head and neck radiation patients. Oper Dent. 2002;27:430-437.

- Lee WC, Eakle WS. Possible role of tensile stress in the etiology of cervical erosive lesions of teeth. J Prosthet Dent. 1984;52:374-380.

- Pegoraro LF, Scolaro JM, Conti PC, Telles D, Pegoraro TA. Noncarious cervical lesions in adults, prevalence and occlussal aspects. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136:1694-1700.

- Dzakovich JJ, Oslak RR. In vitro reproduction of noncarious cervical lesions. J Prosthet Dent. 2008;100:1-10.

- Vieira A, Overweg E, Ruben JL, Huysmans M. Toothbrush abrasion, simulated tongue friction and attrition of eroded bovine enamel in vitro. J Dent. 2006;34:336-342.

- Smith WA, Marchan S, Rafeek RN. The prevalence and severity of non-carious cervical lesions in a group of patients attending a university hospital in Trinidad. J Oral Rehabil. 2008;35:128-134.

- Türkün LS, Celik EU. Noncarious class V lesions restored with a polyacid modified resin composite and a nanocomposite: a two-year clinical trial. J Adhes Dent. 2008;10:399-405.

- Meissner M, Beetke E. Therapy of class V cavities. Stomatol DDR. 1990;40:290-293.

- McLean JW. The clinical development of glass-ionomer cements. 1. Formulations and properties. Aust Dent J. 1977;22:190-195.

- Loguercio AD, Reis A, Barbosa AN. Five-year double-blind randomized clinical evaluation of a resin-modified glass ionomer and a polyacidmodified resin in noncarious cervical lesions. J Adhes Dent. 2003;5:323-332.

- Maneenut C, Tyas MJ. Clinical evaluation of resin modified glass-ionomer restorative cements in cervical “abrasion” lesions: One-year results. Quintessence Int. 1995;26:739-743.

- Miller PD Jr. Root coverage with the free gingival graft. Factors associated with incomplete coverage. J Periodontol. 1987;58:674-681

- Pini Prato GP, Baldi C, Nieri M, Franseschi D, Cortellini P, Clauser C, Rotundo R, Muzzi L. Coronally advanced flap: the post-surgical position of the gingival margin is an important factor for achieving complete root coverage. J Periodontol. 2005;76:713-722.

- Chambrone L, Sukekava F, Araújo MG, Pustiglioni FE, Chambrone LA, Lima LA. Root coverage procedures for the treatment of localised recession-type defects. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2:CD007161.

- Pini Prato GP, Tinti C, Vincenzi G, Magnani C, Cortellini P, Clauser C. Guided tissue regeneration versus mucogingival surgery in the treatment of human buccal recession. J Periodontol. 1992; 63: 919-928.

- Moriyama T, Matsumoto S, Makiishi T. Root coverage technique with enamel matrix deri – vative. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll. 2009;50:97-104.

- McGuire MK. Soft tissue augmentation on previously restored root surfaces. Int J Perio dontics Restorative Dent. 1996;16:570-581.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2010; 8(3): 48-51.