Caring for Patients With Psoriasis

Providing education on oral health modifications as well as anticipating complications and modifying treatment to ensure safe and effective dental hygiene care can help patients with psoriasis maintain their oral health.

This course was published in the December 2022 issue and expires December 2025. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 149

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define psoriasis.

- Explain the characteristics of psoriasis.

- Identify the oral manifestations of psoriasis.

- Discuss dental hygiene strategies to manage patients with psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a common, chronic, immune-mediated, systemic inflammatory skin disease that primarily affects the skin and joints. While the exact etiology of this multisystem disease is unknown, it is likely a combination of genetic, environmental, and immunologic factors.1–3 Psoriasis is also associated with a variety of systemic comorbidities, oral manifestations, and an overall greater risk of mortality. Due to the systemic inflammatory nature of psoriasis, a multidisciplinary, collaborative approach is necessary to effectively manage patient outcomes.2,3 Dental hygienists who are well versed in psoriasis will be more effective in making treatment decisions and in optimizing oral care for patients with psoriasis.

Approximately 125 million people, or 2% to 3% of the world’s population is affected by psoriasis.4,5 Approximately 3% of Americans older than age 20 are affected by psoriasis, making it one of the most widespread systemic immune-mediated diseases among adults.6 Men and women are affected equally, and the incidence of psoriasis among older adults is higher.6 While psoriasis alone is not life-threatening, research suggests patients with severe psoriasis are at 50% greater risk of mortality compared to patients with milder psoriasis; this may be attributed to an association with systemic diseases.3,4

This papulosquamous disease has highly variable morphology, distribution, severity, and course that varies by phenotype. Once diagnosed, the disease is characterized by chronic progression with spontaneous remission in some patients.7 Typically, mild psoriasis affects less than 5% of body surface area (BSA); moderate affects less than 5% to 10% of BSA; and severe impacts greater than 10% of BSA, and/or lesions are present on the hands, feet, face, scalp, or genitals.2

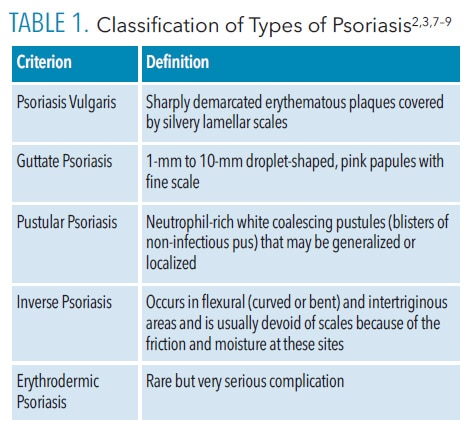

Psoriasis has several clinical phenotypes (Table 1).2–4 Plaque psoriasis, or psoriasis vulgaris, is the most common type, accounting for 90% of cases and is characterized by well-demarcated, erythematous, symmetric plaques with an overlying silvery-white scale that may manifest on the scalp, trunk, buttocks, skin folds, nails, or palmoplantar regions.2,3,7,8 Inverse psoriasis is site-specific and causes inflamed deep-red smooth skin in flexural and intertriginous areas such as the underarms, buttocks, and genitals, and may not have scales due to friction and moisture at these sites.2

Acute and rare, guttate psoriasis is characterized by 1 mm to 10 mm droplet-shaped pink papules with a fine scale, and is primarily seen in patients younger than 30. The guttate variety often appears following a ß-hemolytic or group-α streptococcal infection, tonsillitis, pharyngitis, or viral infection.2,7,8

Relatively rare, pustular psoriasis is characterized by neutrophil-rich, white coalescing pustules that may be generalized or localized to the palms and soles of feet, nails, and tips of fingers and toes, or both. Any form of psoriasis may become erythrodermic, causing intense redness and shedding of the skin in layers—a rare but potentially life-threatening complication.2,8,9

Psoriatic arthritis (PSA) is a chronic inflammatory disease defined by peripheral joint inflammation associated with psoriasis. Approximately 10% to 40% of patients with cutaneous psoriasis will develop PSA within 5 years to 10 years of cutaneous onset.7,10 PSA is characterized by joint erosion, joint space narrowing, bony proliferation, pencil-in-cup-deformity, ankylosis, pain, and swelling. PSA may impact physical function and daily activities and may lead to significant morbidity.2,7,8,10,11

Inflammation is essential in the development of psoriasis and may be a shared characteristic underlying the association between psoriasis and comorbidities.8 Patients with psoriasis may be at increased risk for stroke, adverse cardiovascular events, and related mortality compared to patients who do not have psoriasis.12–14 There may also be a greater prevalence of obesity, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and Type 2 diabetes among individuals with psoriasis compared to the general public.8,15–17 Chronic exposure to smoking and alcohol may also influence the development of psoriasis, affect clinical expression, and increase mortality by interfering with cell-mediated immunity. Research suggests both current and ex-smokers are at an increased risk of psoriasis compared to people who have never smoked; heavy drinkers tend to have more severe psoriatic disease. The relationship between stress, depression, and psoriasis is also complex as psoriatic lesions may be precipitated or exacerbated by stress, and lesions may negatively affect quality of life, leading to significant psychological problems. Self-esteem and body image can be negatively affected by psoriasis.18,19

The etiology of psoriasis is largely unknown, although it is thought to involve a combination of genetic, immunological, and environmental factors.4,5 Psoriasis has a strong genetic predisposition and is thought to be a T-cell-mediated immune dermatosis in which T-cells and dendritic cells are inappropriately activated, causing the release of inflammatory cytokines.20 Infectious pathogens that may provoke or exacerbate psoriasis include Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Malassezia, Candida albicans, papillomaviruses, retroviruses, and endogenous retroviruses. Drugs—including lithium, beta blockers, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and antimalarial agents—may also be associated with the initiation or aggravation of psoriatic disease.2,21

No cure for psoriasis exists, however, patient-centered treatment options are available. Psoriasis is a chronically relapsing disease that often requires long-term therapy. Treatment should consider severity, presence of psoriatic arthritis and other medical conditions, patient preference, clinical needs, benefits, risks, and cost effectiveness.7–9

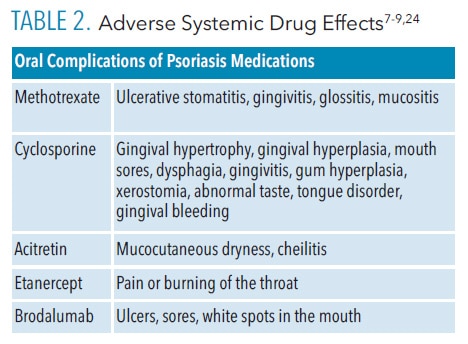

Corticosteroid topical treatment is often used for mild to moderate cases. Systemic treatments—including phototherapy and immunosuppressives such as methotrexate, cyclosporin, and biologics—are often used to treat moderate to severe psoriasis or when topical therapy is ineffective.22 Table 2 lists adverse reactions of systemic medications commonly used to treat mild to severe psoriasis.

Characteristics of Oral Psoriasis

Data regarding oral manifestations of psoriasis are limited, however, oral complications of psoriasis can occur. The clinical appearance of oral psoriasis may be misleading, as it may resemble more common lesions including atrophic candidiasis, stomatitis, diffuse oral erythema, geographic tongue, fissured tongue, erythema migraine, angular cheilitis, Reiter syndrome, erythema circinate, lichen planus, pemphigoid, or leukoplakia.3,23,24 Oral psoriasis lesions are typically asymptomatic, thus, biopsies are rarely done so lesions are often not reported.25 If an oral lesion is detected and treated, an inadequate response to topical or systemic treatments or a biopsy may lead to a differential diagnosis of oral psoriasis.3,23

Oral psoriatic lesions may affect different areas of the oral cavity including the lips, tongue, palate, buccal mucosa, and gingiva.24,25 The buccal mucosa is most frequently involved; lesions affecting the vermillion border, gingiva, and palate are less common.3,24 Oral manifestations may vary in duration or location in conjunction with clinical fluctuations of the cutaneous disease.

Oral psoriasis may be classified into four categories: well-defined gray to yellowish-white round to oval lesions on the mucosa or tongue that are independent of cutaneous lesions; lacy, circinate, white elevated lesions that parallel cutaneous lesions; intense erythema of the entire oral mucosa; and benign migratory glossitis. Fissured tongue and geographic tongue may be the most common oral findings in patients with psoriasis, occurring in 33%, and 10% to 14% of cases, respectively.3,23–25

Dental Hygiene Management

Dental hygienists should be cognizant of management techniques to identify and treat oral manifestations of psoriasis. A thorough patient interview using open-ended questioning to allow the patient to divulge pertinent medical information is necessary. Consultation with the patient’s primary care physician may also be useful to clarify medical issues that could require modifications in dental management.5

Blood pressure should be documented at each appointment due to increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events among patients with psoriasis.16 A thorough medical history should be obtained and updated at each recare appointment as medications frequently change that can trigger or aggravate psoriasis. Patients should be educated about medication interactions and their potential effect on cutaneous lesions.7,21

Several systemic drugs approved to treat psoriasis may have side effects that affect oral tissues (Table 2).22,25 Drug-induced xerostomia should be treated by recommending increased water intake, incorporation of adjuncts that stimulate saliva production or salivary replacements, and avoidance of products containing alcohol, which may further dry oral mucosa. Patients with psoriasis who experience stomatitis, mucositis, and glossitis should be advised to avoid irritants—including hot or spicy foods, alcohol, and tobacco—and use palliative treatments including mucosal protectants or topical anesthetic agents.25

Patients presenting with gingival hyperplasia may require more frequent oral prophylaxis and more rigorous self-care including increased flossing in an effort to reduce bacterial biofilm. Full-mouth scaling and root planing followed by mouthrinsing with 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate solution for 2 minutes and subgingival irrigation of pockets with a 1% chlorhexidine gel may result in significant clinical improvements for patients experiencing drug-induced gingival overgrowth.26

During the medical history, clinicians should ask questions regarding lifestyle habits including tobacco and alcohol use, diet, and exercise. Patients should be encouraged to adopt healthy lifestyle changes including smoking cessation, which may prevent onset and alleviate psoriasis disease severity, improve quality of life, and lengthen life span.16,27 Additionally, alcohol abstinence may induce remission of psoriatic lesions.28 Patients should also be encouraged to minimize their cardiovascular risk factors to prevent incidents that may cause damage to the heart muscle.

To identify oral psoriatic lesions or changes in the oral environment, a thorough intraoral exam of oral tissues including the lips, tongue, palate, buccal mucosa, and gingiva should be completed at every appointment. Oral manifestations suggestive of psoriasis may include small whitish papules, red and whitish plaques, or bright red patches; these should be documented in the patient record and revealed to the patient if identified. Clinicians should document the size, shape, location, severity, and duration in the patient record. In the event a lesion cannot be definitively diagnosed, the dental hygienist should provide a referral for a histological assessment to rule out differentiating pathology.25

If an oral lesion is detected or if a patient reports adverse oral effects from a systemic psoriasis treatments, dental hygienists may recommend palliative treatments such as topical anesthetic agents, topical corticosteroids, emollient toothpaste as a mucosal protectant, or salivary substitutes to reduce irritation. Dental hygienists should also focus on removing irritants and biofilm, recommending restorative treatment for caries lesions, adjusting poorly fitting prosthetics, and ensuring the integrity of existing teeth to improve or maintain clinical outcomes.25

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) of patients with psoriasis should also be evaluated at each recare appointment by performing a thorough extraoral examination. This may include an evaluation of the patient’s ability to open and close; palpation of the TMJ and masticatory and cervical muscles to detect tenderness and nodularity; and asking open-ended questions about symptoms. Clinicians may also consider recommending imaging techniques including radiographs, computed tomography, scintigraphy, ultrasound, or magnetic resonance imaging to diagnose or evaluate the extent of TMJ disorder related to psoriatic arthritis.29

Patients who experience TMJ symptoms due to psoriatic arthritis may present with limited opening and jaw fatigue. A mouth prop, multiple breaks, and shorter appointments may make dental treatment more comfortable. Treatment options including biologics, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, NSAIDs, jaw rest with a soft diet, avoidance of wide mouth opening, and physiotherapy to slow or prevent the degradation of the TMJ.29 A custom nightguard or soft occlusal split may also be prescribed as a palliative treatment or to prevent further damage to the TMJ.

Dental hygienists should also be aware of the emotional toll psoriasis may take on patients and encourage them to pursue stress-relieving activities. Self-esteem and body image issues related to visible psoriatic lesions may impact both self-care habits and scheduling of dental hygiene appointments. If the clinician notes the patient is experiencing significant distress, it is important to explore the issue and decide whether referral to a mental health professional or dermatologic support group might help. Additionally, patients should be educated about the relationship between stress and cutaneous lesions.

Patients with cutaneous psoriasis may experience cracked, itching, sore, or bleeding skin, which can make oral self-care difficult.25 Moreover, patients with psoriatic arthritis may experience inflammation of the interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints of the hands or ankylosis of the wrist in late stages, which can affect dexterity and fine motor skills.30

Dental hygienists should evaluate the ability of these patients to complete self-care by asking questions about dexterity, observing oral hygiene techniques, and assessing plaque and calculus accretion levels. Clinicians should also consider recommending products or appropriate adjuncts that may assist the patient in achieving effective oral self-care. Manual toothbrush adaptations, such as a widened or elongated handle, may assist with more effective biofilm control. Self-care may also be improved for some patients with dexterity issues via a powered toothbrush or flosser, use of an interproximal oral irrigator, or a long-handled floss holder instead of string floss.

Due to the association of systemic inflammation and psoriatic disease exacerbation, reducing oral inflammation is imperative. Patients should be educated on the importance of meticulous self-care and strategies to promote effective daily biofilm removal. Methods to decrease oral inflammation with excellent self-care in addition to nonsurgical periodontal therapy should be considered an important course of care for patients with psoriasis and periodontitis.31 A thorough clinical inspection of the alveolar tissue as well as periodontal evaluation at each recare appointment will allow the dental hygienist to assess for signs of inflammation, bleeding, and disease progression, which may indicate worsening of the periodontal status. More frequent recare appointments (every 3 months to 4 months) or referral to a periodontist to address periodontal instability should be considered.

Conclusion

Psoriasis is a complex immune-mediated disorder affecting the skin, nails, scalp, and joints. It is associated with several systemic comorbidities and overall increased mortality. Oral psoriasis may reveal mucosal lesions, affect the periodontium, and cause joint inflammation, which may affect the patient’s quality of life and ability to perform self-care. Moreover, medications used to treat psoriasis may also impact oral tissues. Dental hygienists should be aware of psoriatic conditions to educate patients on oral health modifications, anticipate complications, and modify treatment to ensure safe and effective dental hygiene care.

References

- Younai FS, Phelan JA. Oral mucositis with features of psoriasis: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84:61–67.

- Menter A. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis overview. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(8 Suppl):s216–224.

- Fatahzadeh M. Manifestation of psoriasis in the oral cavity. Quintessence Int. 2016;47:241–247.

- Nestle FO, Kaplan DH, Barker J. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:496–509.

- Brooks JK. Psoriasis: a review of systemic comorbidities and dental management considerations. Quintessence Int. 2018;49:209–217.

- National Psoriasis Foundation. About Psoriasis. Available at: psoriasis.org/world-psoriasis-day. Accessed October 14, 2022.

- Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, Barker JNWN. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2021;397:1301–1315.

- Rendon A, Schäkel K. Psoriasis pathogenesis and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1475.

- Kim WB, Jerome D, Yeung J. Diagnosis and management of psoriasis. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:278–285.

- Mease PJ, Armstrong AW. Managing patients with psoriatic disease: the diagnosis and pharmacologic treatment of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Drugs. 2014;74:423–441.

- Langenbruch A, Radtke MA, Krensel M, Jacobi A, Reich K, Augustin M. Nail involvement as a predictor of concomitant psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:1123–1128.

- Gelfand JM, Dommasch ED, Shin DB, et al. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2411–2418.

- Shahwan KT, Kimball AB. Psoriasis and cardiovascular disease. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99:1227–1242.

- Wu JJ, Choi YM, Bebchuk JD. Risk of myocardial infarction in psoriasis patients: a retrospective cohort study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26:230–234.

- Armesto S, Santos-Juanes J, Galache-Osuna C, Martinez-Camblor P, Coto E, Coto-Segura P. Psoriasis and type 2 diabetes risk among psoriatic patients in a Spanish population. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:128–130.

- Salihbegovic EM, Hadzigrahic N, Suljagic E, et al. Psoriasis and dyslipidemia. Mater Sociomed. 2015;27:15–17.

- Onumah N, Kircik LH. Psoriasis and its comorbidities. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(5 Suppl):s5–10.

- Herron MD, Hinckley M, Hoffman MS, et al. Impact of obesity and smoking on psoriasis presentation and management. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1527–1534.

- Naldi L, Chatenoud L, Linder D, et al. Cigarette smoking, body mass index, and stressful life events as risk factors for psoriasis: results from an Italian case-control study. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:61–67.

- Nussbaum L, Chen YL, Ogg GS. Role of regulatory T cells in psoriasis pathogenesis and treatment. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:14–24.

- Fry L, Baker BS. Triggering psoriasis: the role of infections and medications. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:606–615.

- Menter A, Gelfand JM, Connor C, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis with systemic nonbiologic therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1445–1486.

- Daneshpazhooh M, Moslehi H, Akhyani M, Etesami M. Tongue lesions in psoriasis: a controlled study. BMC Dermatol. 2004;4:16.

- Yesudian PD, Chalmers RJ, Warren RB, Griffiths CE. In search of oral psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2012;304:1–5.

- Dreyer LN, Brown GC. Oral manifestations of psoriasis. Clinical presentation and management. N Y State Dent J. 2012;78:14–18.

- Pundir AJ, Pundir S, Yeltiwar RK, Farista S, Gopinath V, Srinivas TS. Treatment of drug-induced gingival overgrowth by full-mouth disinfection: A non-surgical approach. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2014;18:311–315.

- Poikolainen K, Karvonen J, Pukkala E. Excess mortality related to alcohol and smoking among hospital-treated patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1490–1493.

- Higgins E. Alcohol, smoking and psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:107–110.

- National Psoriasis Foundation. When PSA Invades the Jaw. Available at: psoriasis.org/advance/when-psa-invades-the-jaw. Accessed October 14, 2022.

- Sankowski AJ, Lebkowska UM, Cwikła J, Walecka I, Walecki J. Psoriatic arthritis. Pol J Radiol. 2013;78:7–17.

- Ucan Yarkac F, Ogrum A, Gokturk O. Effects of non-surgical periodontal therapy on inflammatory markers of psoriasis: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2020;47:193–201.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November/December 2022;20(11)34-37.