NATALIE KARPENKO / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

NATALIE KARPENKO / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Support the Health of Patients With Type 2 Diabetes

Oral health professionals should be knowledgeable about this metabolic disorder’s pathophysiology, characteristics, systemic and oral health manifestations, and oral care considerations.

This course was published in the December 2022 issue and expires December 2025. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 149

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the prevalence and risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

- Explain the treatment for T2DM.

- Identify oral manifestations of this metabolic disorder in addition to patient management strategies.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a chronic metabolic disorder and leading health concern in the United States due to its growing prevalence and associated health complications.1 Diabetes can cause complications throughout the body, including the oral cavity.2–4 To provide optimal care, oral health professionals should be knowledgeable about T2DM’s pathophysiology, characteristics, systemic and oral health manifestations, and oral care considerations.

In health, beta cells in the pancreas produce insulin, which allows glucose uptake by the cells. T2DM is characterized by the inability to appropriately use insulin (insulin resistance), and the compromised ability of pancreatic beta cells to secrete enough insulin, leading to elevated blood glucose (hyperglycemia).5 The hormone insulin is responsible for using glucose to produce energy in cells and glucose conversion into glycogen for storage.5,6 Adipose tissue, or fat cells, also contribute to insulin resistance.3,5

T2DM accounts for 90% to 95% of all diabetes cases and is influenced by age, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status (SES), diet, and physical activity level.5–7 In the United States 34.1 million or 13% of adults ages 18 and older have diabetes with approximately 7.3 million, or 2.8% remaining undiagnosed.7 The prevalence of diabetes increases with age. An additional 88 million adults are prediabetic, a risk factor for developing T2DM.7

Genetic factors—such as ethnicity, family history, and genetic predispositions—may influence the likelihood of developing T2DM; however, studies show a strong correlation between improvements of modifiable risk factors and disease prevention.5 Environmental factors such as sedentary lifestyle, reduced sleep, obstructive sleep apnea, endocrine disruptors, and the gut microbiota are also related to diabetes risk.6 Risk factors for developing T2DM include: low amounts of physical activity, increased body mass index, smoking, history of gestational diabetes or other metabolic disorders, hypertension, systemic inflammation, and older age.8

Diagnosis and cCharacteristics

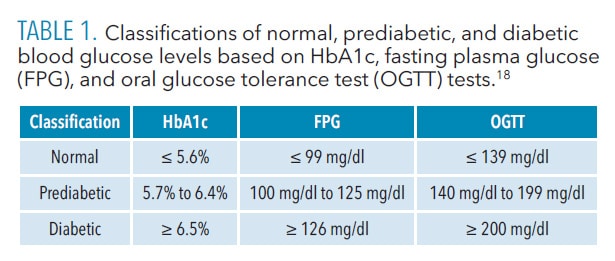

The diagnosis of T2DM requires a blood test (Table 1). The HbA1c test measures the average blood glucose level over the past 2 months to 3 months; a result of 6.5% or higher indicates diabetes. The fasting plasma glucose test requires 8 hours of fasting; a result of 126 mg/dl or higher indicates diabetes.

Hyperglycemia causes narrowing of blood vessels, impeding blood flow and damaging organs such as the eyes and kidneys, as well as the integumentary, nervous, circulatory, and immune systems.2,5 Chronic high blood glucose can lead to an impaired immune system. Common symptoms of T2DM include polyuria (increased urination), polyphagia (increased hunger), and polydipsia (excessive thirst). Other symptoms include weight loss, fatigue, recurrent infections, and dark patches on the skin of the neck, under arms, and groin.9

People with T2DM are at higher risk for developing cardiovascular disease (CVD).1,5,10 Furthermore, individuals with T2DM are more likely to experience a stroke, hypertension, atherosclerosis, and kidney disease than people without diabetes. 1–3,5,10,11

Patients with T2DM are more likely to experience hearing impairment and diabetic retinopathy.11-13 Hearing impairment may be caused by hyperglycemia, which weakens the nerves and blood vessels in the inner ear. Diabetic retinopathy is the most common complication of diabetes13 and occurs when hyperglycemia causes blood vessels in the retina to expand and discharge fluid into the eye. Eventually, the retina can detach from the underlying tissue, causing blindness.

Skin complications may be the first sign of diabetes, including diabetic dermopathy (small lesions and spots on bony parts of the body), necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (skin rashes that mostly affect the shin area in women), diabetic blisters, eruptive xanthomatosis (small yellow-red raised lesions anywhere on the body), and bacterial and fungal infections.14

Nerve damage, or neuropathy, is another complication of T2DM; it can occur anywhere in the body but frequently impacts the feet.11,15,16 Neuropathy, in addition to poor circulation, in the feet may raise the risk of infection and ulcerations, and, in severe cases, may lead to amputation.15,16

Treatment

Treatment of T2DM involves managing blood glucose levels typically through medication use, routine blood glucose monitoring, and changes in diet and physical activity.17 Patients should self-monitor blood glucose regularly and have their HbA1c levels checked every 3 months to 6 months. For patients taking insulin, self-monitoring of blood glucose may be needed several times a day. Additionally, people with diabetes should aim for an HbA1c of less than 7%.18

Patient education can help with medication and treatment compliance. In general, patients with T2DM should practice good oral and skin hygiene, use stress management strategies, eat a balanced diet, exercise regularly, avoid smoking, monitor blood glucose regularly, and keep routine visits with an endocrinologist. Although there is currently no cure for T2DM, pharmacological therapies can effectively help manage the disease.17

Metformin is the primary medication used to manage T2DM. It works by reducing the amount of glucose the body produces and helping move glucose from the blood into cells.17 For more advanced T2DM, an insulin pump may be necessary. While insulin pumps were first introduced to treat Type 1 diabetes, they are also used for T2DM. Insulin pumps can deliver continuous amounts of insulin throughout the day to better regulate blood glucose levels.19 Additionally, bariatric surgeries may be recommended for patients with T2DM if they have a body mass index of 35 or more.20,21

Oral Manifestations

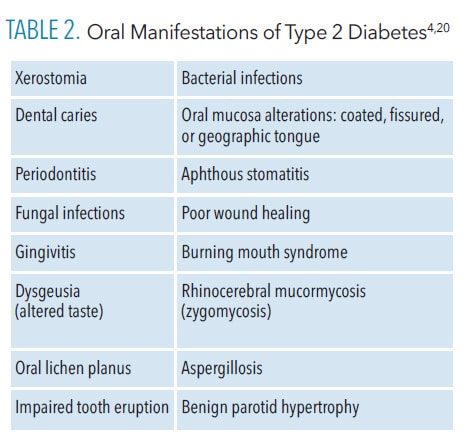

T2DM often causes oral manifestations, which can be challenging to manage (Table 2). Routine, preventive oral hygiene services are particularly important for patients with T2DM. Xerostomia is a common oral complication of T2DM.4 This association may be related to polyuria (changes in the salivary glands leading to decreased salivary flow) or a side effect of medication prescribed for diabetes. Studies show that 4% to 51% of individuals with diabetes report xerostomia.22–27

Dental caries is also increased among patients with T2DM.22,28,29 One study found people with diabetes had lower mean salivary pH compared to people without diabetes (4.83 vs 5.90) and lower mean salivary calcium levels than people without diabetes (0.74 mmol/L vs 5.58 mmol/L). These lower levels create a more conducive environment for demineralization and caries formation.29

Fungal infections, such as oral candidiasis, are another common oral manifestation of T2DM due to reduced saliva, hyperglycemia, and impaired immune function. Other risk factors for fungal infections include smoking, wearing dentures, and HbA1c levels more than 12%.30 Studies show between 2% and 24.3% of patients with T2DM experience oral candidiasis.26,27,31

Diabetes and periodontitis are both chronic, inflammatory diseases with a bidirectional relationship.32 Studies show between 45.3% and 58% of patients with T2DM experience periodontitis.24–26 Blood glucose levels influence the severity of periodontitis and periodontal therapies have shown short-term improvements in HbA1c levels.22,32,33 Poor glycemic control is correlated with the development and progression of periodontitis.22,32 Periodontitis and diabetes share common risk factors such as older age, male gender, minority race/ethnicity, low SES, genetic predisposition, smoking, obesity, low activity level, and poor diet.32

Patient Management

Assessment is the first step in effective management of patients with T2DM, and it begins as soon as patients enter the dental office. A patient who is limping may be experiencing neuropathy or a skin/foot complication. Alternatively, a patient wearing open footwear may display obvious signs of infection on his or her feet. Due to the millions of people with undiagnosed diabetes, it is important for oral health professionals to assess for risk factors of diabetes. Specifically, oral health professionals can perform chairside HbA1c testing to screen for T2DM and, if diabetes is suspected, refer patients to their primary care physician for a definitive diagnosis.

An interdisciplinary approach to T2DM will help clinicians create comprehensive treatment plans that meet patients’ systemic and oral health needs. Prophylactic antibiotics for routine dental procedures are not typically recommended when diabetes is the only risk factor.34 However, for patients with uncontrolled diabetes, medical clearance from the patient’s endocrinologist or primary care provider may be prudent prior to dental hygiene treatment.35

The patient’s medical history should be updated at every appointment and include documenting whether they recently ate, current blood glucose levels, latest HbA1c number, and medication usage along with their oral implications. HbA1c tests are the most accurate way to measure blood glucose control.34 Blood pressure should be documented in the medical history at every visit for patients with T2DM because of the strong association between diabetes and CVD, including hypertension.

Oral health professionals should be cognizant of extraoral and intraoral manifestations of T2DM such as dark patches of skin on the neck, oral lichen planus, fissured tongue, geographic tongue, aphthous stomatitis, oral candidiasis, and xerostomia. If the patient has oral candidiasis, antifungal medications, such as nystatin, miconazole, or oral fluconazole, may be prescribed.36 If a mucosal infection is evident, the patient’s primary care physician should be consulted to see if it is related to blood glucose levels. If the oral mucosa or tongue appear dry or the patient reports xerostomia, he or she should be advised to avoid smoking and alcohol, stay hydrated, utilize saliva substitutes, use products that contain fluoride and xylitol, and consider prescription medications.

Due to the high risk of caries for people with T2DM, education on biofilm control is imperative. Fluoride varnish should be applied every 3 months to 6 months. Prescription-strength fluoride products should also be recommended.37 Discussing how biofilm and fermentable carbohydrates contribute to caries risk is important for patient compliance. Referring patients to a registered dietitian for nutritional therapy may be beneficial for improving the patient’s HbA1c number.38 In fact, a systematic review of the literature showed people with T2DM who apply healthy behavior interventions provided by a registered dietitian improved their glycemic control.37

Uncontrolled diabetes can result in higher rates of alveolar bone destruction, soft tissue destruction, and tooth loss. Similarly, uncontrolled periodontal diseases can cause systemic inflammation and increase the difficulty of blood glucose management. In 2017, a new classification system for periodontal diseases was developed to include a system for staging a grading a patient with periodontitis. Periodontitis grading is intended to assess the rate of progression, patients’ abilities to respond appropriately to therapeutic procedures, and the potential impact on their overall health. Periodontitis grading is dependent on the amount of radiographic bone loss or clinical attachment loss, percent of bone loss divided by age, and amount of biofilm present. Grade modifiers are risk factors such as cigarette smoking and diabetes that affect the rate of progression. Grades consist of Grade A: slow rate; Grade B: moderate rate; and Grade C: rapid rate.39

All patients with T2DM and periodontitis are initially a Grade B. Patients with diabetes and a HbA1c under 7% will remain at Grade B if no factors related to Grade C are present; however,7% or higher may result in a Grade C classification.38 Patients should be educated on how their HbA1c could affect future attachment loss and response to periodontal therapy. Additionally, invasive procedures, such as periodontal scaling and root planing, should be planned carefully due to T2DM impacting the immune system and impairing wound healing. Patients with diabetes may need more frequent dental hygiene appointments especially if they have periodontitis.

Patients with diabetes should have dental appointments in the morning, after they normally eat breakfast and take their medications. However, patients may not eat prior to their dental appointment and unintentionally administer too much insulin, resulting in a hypoglycemic incident (blood glucose concentration of < 70 mg/dl) with rapid progression and little forewarning. The patient may exhibit signs and symptoms such as cold, clammy skin; nausea; irregular speech patterns; tachycardia; and confusion. If not addressed immediately, the patient’s blood pressure can drop, resulting in unconsciousness, seizures, and even death. Administration of any high-sugar containing food or beverage, such as fruit juices or candy, can help. If the patient does not improve within minutes, emergency medical services should be contacted.34,40

Conclusion

T2DM is a chronic metabolic disorder that impacts the entire body. Common oral manifestations of T2DM include xerostomia, dental caries, oral candidiasis, and periodontal diseases. Oral health professionals should be prepared to recognize oral and extraoral signs and symptoms of T2DM, patient management strategies, and oral self-care modifications. Additionally, oral health professionals should make appropriate modifications when treating patients with T2DM in order to provide optimal oral care.

References

- Schmidt A. Highlighting diabetes mellitus: the epidemic continues. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38:e1–e8.

- Leite R, Marlow N, Fernandes J. Oral health and type 2 diabetes. Am J Med Sci. 2013;345:271–273.

- Kanter JE, Bornfeldt KE. Impact of diabetes mellitus. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:1049–1053.

- Mauri-Obradors E, Estrugo-Devesa A, Jané-Salas E, Viñas M, López-López J. Oral manifestations of diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2017;1:22:e586–594.

- Galicia-Garcia U, Benito-Vicente A, Jebari S, et al. Pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:6275.

- Skyler JS, Bakris GL, Bonifacio E, Darsow T, et al. Differentiation of diabetes by pathophysiology, natural history, and prognosis. Diabetes. 2017;66:241–255.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report 2020. Available at: cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed Oral 13, 2022.

- Bellou V, Belbasis L, Tzoulaki I, Evangelou E. Risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus: an exposure-wide umbrella review of meta-analyses. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0194127.

- Ramachandran A. Know the signs and symptoms of diabetes. Indian J Med Res. 2014;140:579–581.

- Strain WD, Paldánius PM. Diabetes, cardiovascular disease and the microcirculation Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17:57.

- Forbes JM, Cooper ME. Mechanisms of diabetic complications. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:137–188.

- Samocha-Bonet D, Wu B, Ryugo DK. Diabetes mellitus and hearing loss: a review. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;71:101423.

- Simó-Servat O, Hernández C, Simó R. Diabetic retinopathy in the context of patients with diabetes. Ophthalmic Res. 2019;62:211–217.

- Sanches MM, Roda Â, Pimenta R, Filipe PL, Freitas JP. Cutaneous manifestations of diabetes mellitus and prediabetes. Acta Med Port. 2019;32:459–465.

- Dong J, Chen L, Zhang Y, et al. Mast cells in diabetes and diabetic wound healing. Adv Ther. 2020;37:4519–4537.

- Hicks CW, Selvin E. Epidemiology of peripheral neuropathy and lower extremity disease in diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19:86.

- Artasensi A, Pedretti A, Vistoli G, Fumagalli L. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: a review of multi-target drugs. Molecules. 2020;25:1987.

- American Diabetes Association. Understanding A1C. Available at: diabetes.org/diabetes/a1c. Accessed October 13, 2022.

- Landau Z, Raz I, Wainstein J, Bar-Dayan Y, Cahn A. The role of insulin pump therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2017;33:1002.

- Celio AC, Pories WJ. A history of bariatric surgery: the maturation of a medical discipline. Surg Clin North Am. 2016;96:655–667.

- Affinati AH, Esfandiari NH, Oral EA, Kraftson AT. Bariatric surgery in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19:156.

- Rohani B. Oral manifestations in patients with diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes. 2019;10:485-489.

- Lessa LS, Pires PD, Ceretta RA, et al. Meta-analysis of prevalence of xerostomia in diabetes mellitus. Int Arch Med. 2015;8:1–13.

- Choudhary A, Sharma H, Choudhary H. Prevalence of oral manifestations in diabetic patients. IJCHMR. 2019;5:89–91.

- Kathiresan TS, Masthan KMK, Sarangarajan R, Babu A, Kumar P. A study of diabetes associated oral manifestations. J Pharm Bioall Sci. 2017;9S211–9S216.

- Ghadiri-Anari A, Kheirollahi K, Hazar N, et al. Frequency of oral manifestations in diabetic patients in Yazd 2016-2017. Iranian Journal of Diabetes and Obesity. 2020;12(2):63–68.

- Bangash RY, Khan AU, Tariq KH, Yousaf A. Oral aspects and complications in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a study. Pakistan Oral & Dental Journal. 2012;32(2):296–299.

- Singh I, Singh P, Singh A, Singh T, Kour R. Diabetes an inducing factor for dental caries: a case control analysis in Jammu. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2016;6:125–129.

- Singh A, Thomas S, Dagli RJ, Kaţ R, Solanki J, Bhateja GA. To access the effects of salivary factors on dental caries among diabetic patients and non diabetic patients in Jodhpur City. J Adv Oral Res. 2014;5:10–14.30.

- Ahmad P, Akhtar U, Chaudhry A, Rahid U, Sail S, Asil JA. Repercussion of diabetes mellutis on the oral cavity. European Journal of General Dentistry. 2019;8(3):55–62.

- Moosa Y, Shahzad M, Shaikh AA, Matloob SA, Khalid AM. Influence of diabetes mellitus on oral health. Pakistan Oral & Dental Journal. 2018;38(1):67–70.

- Kocher T, König J, Borgnakke WS, Pink C, Meisel P. Periodontal complications of hyperglycemia/diabetes mellitus: Epidemiologic complexity and clinical challenge. Periodontol 2000. 2018;78:59–97.

- Sanz M, Ceriello A, Buysschaert M, et al. Scientific evidence on the links between periodontal diseases and diabetes: Consensus report and guidelines of the joint workshop on periodontal diseases and diabetes by the International diabetes Federation and the European Federation of Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45:138–149.

- Haveles, EB. Applied Pharmacology for the Dental Hygienist. 7th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier, Mosby; 2016.

- Miller A, Ouanounou A. Diagnosis, management, and dental considerations for the diabetic patient. J Can Dent Assoc. 2020;86:k8.

- Quindós G, Gil-Alonso S, Marcos-Arias C, et al. Therapeutic tools for oral candidiasis: current and new antifungal drugs. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Buccal. 2019:1;24:e172–180.

- Weyant RJ, Tracy SL, Anselmo TT, et al. Topical fluoride for caries prevention: executive summary of the updated clinical recommendations and supporting systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:1279–1291.

- Dobrow L, Estrada I, Burkholder-Cooley N, Miklavcic J. Potential effectiveness of registered dietitian nutritionists in healthy behavior interventions for managing type 2 diabetes in older adults: a systematic review. Front Nutr. 2022;8:737410.

- Tonetti MS, Greenwell H, Kornman KS. Staging and grading of periodontitis: framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S159–S172.

- Grimes, EB. Medical Emergencies: Essentials for the Dental Professional. 2nd ed. London: Pearson; 2014.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November/December 2022;20(11)38-41.