SCIEPRO/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

SCIEPRO/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Caring for the Patient with a Spinal Cord Injury

Understanding the clinical implications and the barriers to care faced by patients with this type of disability is key to helping them maintain their oral health.

This course was published in the February 2022 issue and expires February 2025. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the types of spinal cord injuries (SCIs).

- Discuss the barriers faced by individuals with SCIs when trying to access professional oral healthcare services.

- Describe the clinical implications of treating patients with this type of injury.

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke defines spinal cord injury (SCI) as damage to the cells and nerves that send and receive information from the brain to and from the body.1 The National Spinal Cord Injury Statistics Center reports that approximately 296,000 people in the United States are living with a SCI.2 While roughly 38.2% of injuries occur as a result of trauma in a motor vehicle accident, some are caused by falls, acts of violence, and sports injuries.2,3 Some individuals experience a SCI with little or no cell death and achieve a full recovery, while others experience more serious complications that can result in paralysis.1

Complete SCI, which occurs in approximately 50% of all cases, is defined as a total loss of all motor and sensory function below the level of where the injury occurred (eg, paraplegia and quadriplegia). Incomplete SCI indicates there is still some function below the level of injury.1,2 SCI can lead to long-lasting and challenging disability including temporary and permanent functional impairment. Individuals with SCI confront diverse types of impairments and limitations of activities. Secondary complications include respiratory and cardiovascular problems, pressure sores, spasticity, depression, osteoporosis and bone fractures, central pain, obesity, and urinary and bowel complications.

Types of Spinal Cord Injury

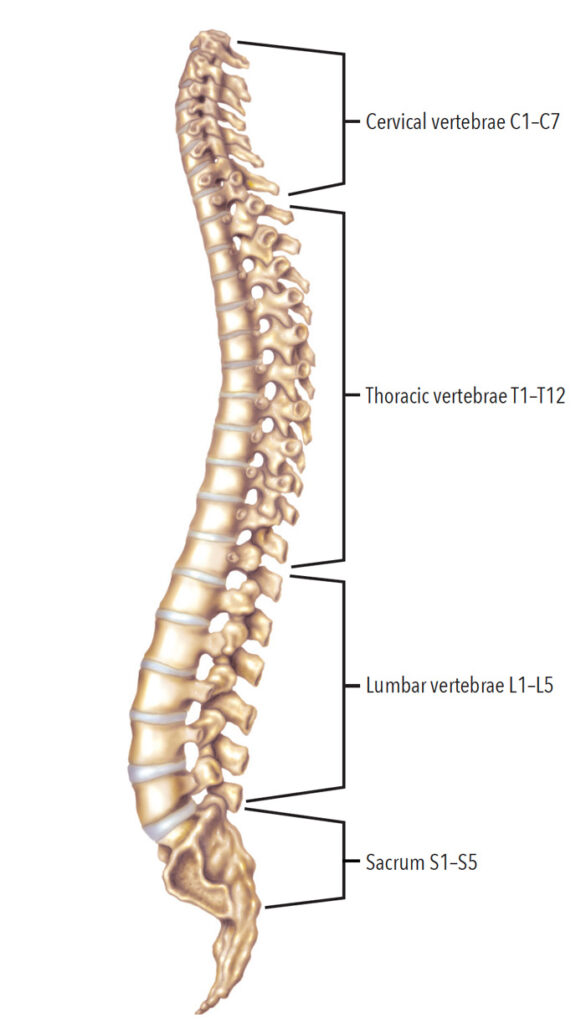

Each of the four sections of the spine—cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral—protect different groups of nerves. The type and severity of the injury depend on what section of the spinal cord is injured (Figure 1).4 Cervical spinal injuries affect the head and neck region above the shoulders; they are the most severe. Most individuals will require 24-hour care in spinal injury units.5 Individuals with cervical SCIs may have trouble breathing on their own, speaking, and controlling their bladder or bowel movements; these patients will rely on specialists in spinal injury units for oral healthcare.4,5

Thoracic SCIs include vertebrae in the middle and upper part of the back. Injuries at the thoracic level will affect the upper chest, mid-back, and abdominal area, with arm and hand function usually remaining the same. Lumbar, or lower back injuries, also affect the leg and hip area, but an individual may be able to walk with the help of leg braces. Lastly, injury at the sacral area, or base of the lumbar region, affects leg and hip function. Individuals with a sacral injury will most likely be able to walk without assistance.

With all types of SCIs, there may be a partial or complete loss of bowel and bladder function.4 Individuals with SCI can present with a variety of complications characterized by multiple organ dysfunctions. Complications, such as neurogenic pain, anxiety and depression, respiratory infection, pulmonary failure, cardiovascular disease, liver damage, kidney dysfunction, urinary tract infection, and increased susceptibility to infection, are common in individuals with SCI.6

Access to Care Barriers

Physical, financial, psychological, and social limitations can create significant barriers to care for those with SCIs.3,7,8 Among individuals with SCIs, 87% report difficulty accessing healthcare, with dental services being among the most difficult.9 Despite the enactment of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, physical barriers, such as lack of wheelchair access, narrow doorways, inaccessible toilets, lack of ramps, and inadequate parking and public transport, still exist.7,10

Financial barriers include healthcare providers who do not accept Medicare or Medicaid and a lack of employment opportunity.10,11 For survivors of SCI, the cost of the first year alone can reach $1.1 million with the average cost being about $191,436 each year thereafter.2 Poverty due to healthcare cost and limited employment opportunities poses a significant barrier to community reintegration. If individuals with SCI can prove they are unable to work, they may apply for disability benefits through the Social Security Administration (SSA).12 Social Security Disability Insurance is based on the individual’s past work history and work earnings. This insurance can provide monthly benefits and provides access to Medicare, however, one must be disabled for 24 months and satisfy SSA guidelines to qualify.12 Medicaid is another disability government program with federal and state requirements that must be met to qualify.13

In addition to physical and financial barriers, individuals with SCI experience psychological barriers such as fear of the negative attitudes of healthcare workers toward their injury. In one study, healthcare workers did not recognize the importance of providing oral care to individuals with SCIs. Only 70.9% of surveyed healthcare workers indicated they had a role in providing oral healthcare to individuals with SCI, with only 60% of those reporting that the role was important.8 Additional psychological fear may also be associated with experiencing asphyxiation while undergoing dental procedures due to a compromised respiratory musculature.14,15

The dental office environment remains a social limitation faced by individuals with SCI.16,17 Excessive wait times often faced in dental offices pose a barrier for patients with SCI with bladder and bowel problems and pressure ulcers. Additionally, some patients with SCIs reported dental office staff as being judgmental of their disability, rude, disrespectful, and uncompassionate.9 Lastly, a lack of dental training regarding transferring individuals in wheelchairs to the dental chair may cause anxiety in this population.

Several studies reported that training on how to successfully treat patients with disabilities was deficient, with only 53% of dentists in the US receiving training in this area.3 Although most dental hygiene programs include special needs education, additional comprehensive education is warranted for meeting the needs of individuals with SCIs. Practitioners can also take an active role in providing resources for patients to help navigate these barriers.

Clinical Implications

Adults with SCIs are just as likely as the general population to visit the dentist annually, however, most access emergency dental care services vs preventive care.15 Inferior general and oral health in addition to higher rates of caries and periodontal diseases are predominant concerns.11 Moreover, smoking is prevalent among those with SCIs, which may be due to lower socioeconomic status and a decreased likelihood of receiving cessation counseling. Motor and/or sensory impairment may influence the effectiveness of cessation interventions.4,18

Dental health issues common among individuals with SCIs include caries, xerostomia, periodontal diseases, biofilm accumulation, inflammation, toothaches, and tooth mobility.11 In a study evaluating oral exams of individuals with SCIs, an average of 32% had their teeth professionally cleaned in the last year.14 The same study showed less than 40% of those with SCIs had been shown how to perform proper oral hygiene tasks with their injuries. Participants reported the presence of current oral health problems and pain within the last 12 months and 64% had periodontal diseases.14,15 Anticholinergic side effects associated with medications for spasticity, depression, and bladder control can cause xerostomia, creating difficulty in tasting, chewing, swallowing, and speaking. Xerostomia also raises the risk for dental caries, demineralization of teeth, tooth sensitivity, and/or oral infections.15,19,20

Many individuals with severe upper extremity limitations can be taught to use a mouthstick, bite stick, or intraoral dental prostheses to assist with everyday tasks such as driving, signing their names, and typing. However, mouthsticks can harbor bacteria and contribute to the wear and trauma of the dentition.14,21–24 Mouthsticks should be cleaned after every use with hot soapy water and/or 70% isopropyl alcohol to prevent bacterial growth. A healthy and stable periodontium is critical for the success of a mouthpiece device.21

Autonomic dysreflexia (AD), a secondary complication of SCI, is a potentially life-threatening cardiovascular emergency especially when the injury is above T6.25,26 Although rare, AD can occur when the injury is below T6. It is defined as a sudden, significant rise in the systolic and diastolic blood pressures accompanied by bradycardia or tachycardia.25 Risk of stroke increases by 300% to 400%. AD may occur up to 40 times per day in susceptible individuals and is most often caused by a full bladder, bowel distension, or retention. Other irritants, such as tight-fitting clothing, kidney stone, urinary tract infection, ingrown toenails, hemorrhoids, or chronic pain, can also cause AD. AD should be strongly suspected in any patient with a SCI and a lesion above T6 who complains of a headache.25

In the event of a suspected AD episode, blood pressure should be monitored every 5 minutes. Sitting the patient in an upright position and loosening any tight clothing may help lower blood pressure. Activation of the emergency response system is recommended if the blood pressure does not drop when in the upright position or when the bladder or bowel are emptied.25,27 Oral health professionals who treat patients with SCI must be able to identify, evaluate, and manage AD.26

![TABLE 1. Adaptive Procedures and Recommendations]() Role of the Oral Health Care Professional

Role of the Oral Health Care Professional

A comprehensive medical history and consultation with specialists enable an interdisciplinary approach to care, including customized individualized appointment considerations as well as a record of all healthcare professionals on the patient’s team. Besides physicians, nurses, and dental hygienists, members of the interprofessional team may include occupational therapists, psychologists, dietitians, and speech-language pathologists (SLP). Identifying any barriers reported by the patient or caregiver can assist the dental team in creating an adaptive and comfortable environment. Compassion is key as individuals with SCIs often experience chronic debilitating pain during ordinary tasks such as sitting in the dental chair.28 Dental team members should show empathy, compassion, and encouragement by responding in a nonjudgmental manner and allowing individuals to exercise control of their appointment. The tell-show-do approach and introducing a stop signal when a break is needed can help reduce anxiety. Table 1 (page 40) shows additional adaptive procedures and recommendations.

Risk management as a way to avoid a medical emergency in individuals with SCIs is important. Among individuals with high thoracic and cervical injuries, 74% experience orthostatic hypotension when assuming an upright seating position.26 The dental chair should be raised slowly to avoid complications such as light-headedness, fatigue, headache, sweating, yawning, and blurred vision.22,26,29 Though an individual with an SCI may often present with low blood pressure (BP), consequences of abnormal cardiovascular control or medications can cause fluctuating BP.26,30 A baseline BP provides valuable information in the event of a medical emergency.

Pain control is important. Nitrous oxide can be used to reduce anxiety and discomfort and increase tolerance for the appointment.31 According to the American Heart Association and the American Dental Association, there is no contraindication for the use of a vasoconstrictor in local anesthetic in this patient population.32,33 However, because an individual with SCI may experience cardiac dysfunction, a maximum dose of 0.04 mg of the vasoconstrictor should be considered.34

Collaboration with an occupational therapist regarding oral care skills can improve oral health. A consultation with a psychologist is recommended to assure that the patient’s emotional and mental needs are being met due to the frequent association of anxiety and depression with SCI.35 Urinary and bowel complications, as well as pressure wounds, can be moderated with proper nutrition.36 The presence of dysphagia increases the risk of malnutrition.5 Providing a referral for a nutritionist for diet analysis and an SLP for a swallow test is vital in providing a holistic approach for overall care.

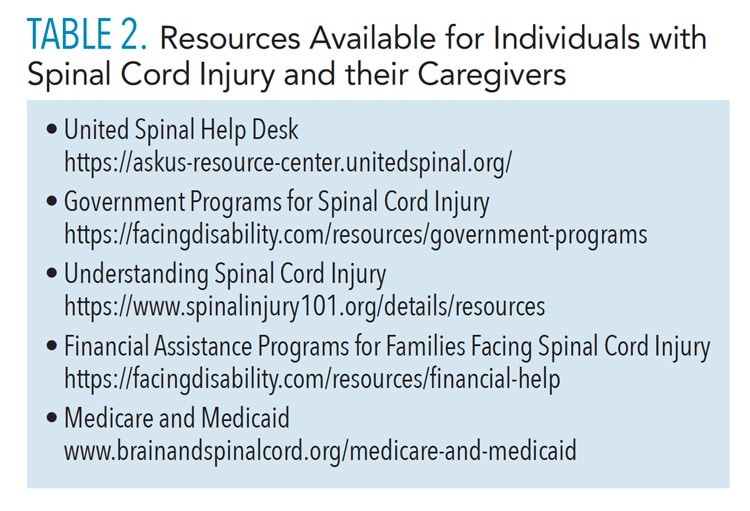

Finally, a list of community-related disability resources should be readily available in the dental office (Table 2, page 41).16 These resources provide individuals with SCI and their families financial, employment, transportation, home modification, government assistance, and caregiver support services. Addressing access to resources can help increase social reintegration into community and employment settings, provide support groups for caretakers and individuals with SCI, and decrease stressors associated with psychological and financial burdens.

![TABLE 2. Resources Available for Individuals with Spinal Cord Injury and their Caregivers]() Conclusion

Conclusion

Challenges will always be present for individuals with SCIs and their families. Oral health professionals are in a unique position to provide oral care and collaborate with interprofessional health care teams to address physical, psychological, financial, and social barriers. Dental professionals must become familiar with secondary complications to SCI to prevent emergencies and provide emotional and physical support to patients. Regular prophylaxes and dental examinations should be encouraged to mitigate the commonly occurring dental health problems among those with SCIs.

References

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Spinal Cord Injury Information. Available at: ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Spinal-Cord-Injury-Information-Page. Accessed January 26, 2022.

- National Spinal Cord Injury Statistic Center. Spinal Cord Injury Facts and Figures at a Glance. Available at: nscisc.uab.edu/Public/Facts%20and%20Figures%20-%202021.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2022.

- Sullivan AL, Morgan C, Bailey JH. Dental professionals’ knowledge about treatment of patients with spinal cord injury. Spec Care Dentist. 2009;29:117–122.

- Shepherd Center Rehabilitation. Spinal Cord Injury Levels and Types. Available at: shepherd.org/patient-programs/spinal-cord-injury/levels-and-types. Accessed January 26, 2022.

- McRae J, Smith C, Emmanuel A, Beeke S. The experiences of individuals with cervical spinal cord injury and their family during post-injury care in non-specialised and specialised units in UK. BMC Health Services Research. 2020;20:783.

- Sun X, Jones ZB, Chen XM, Zhou L, So KF, Ren Y. Multiple organ dysfunction and systemic inflammation after spinal cord injury: a complex relationship. J Neuroinflammation. 2016;13:260.

- Reis J, Breslin M, Lezzoni L. It takes more than ramps to solve the crisis of healthcare for people with disabilities. CMAJ. 2006;175:329.

- Alfaqeeh AA, Assery MK, Ingle NA. Oral health care in patients with spinal cord injury: A systematic review. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2020;10:1222–1228.

- Sullivan AL, Holder R, Dellinger T, Garner A, Bailey J. Exploring obstacles for dental care among the SCI population. Int J Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;04:07.

- Akter F, Islam S, Haque O, et al. Barriers for individuals with spinal cord injury during community reintegration: a qualitative study. Int J Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;7:7.

- Yuen HK, Shotwell MS, Magruder KM, Slate EH, Salinas CF. Factors associated with oral problems among adults with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32:408-415.

- Disability Benefits Health. Benefits of Applying for SSDI With A Spinal Cord Injury? Available at: disability-benefits-help.org/benefits-of-ssdi/spinal-cord-injury. Accessed January 26, 2022.

- Medicare and Medicaid. Brain and Spinal Cord. Available at: brainandspinalcord.org/medicare-and-medicaid/. Accessed January 26, 2022.

- Sullivan AL, Bailey JH, Stokic DS. Predictors of oral health after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:300–305.

- Yuen HK, Wolf BJ, Bandyopadhyay D, Magruder KM, Selassie AW, Salinas CF. Factors that limit access to dental care for adults with spinal cord injury. Spec Care Dentist. 2010;30:151–156.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Environmental barriers to health care among persons with disabilities–Los Angeles County, California, 2002-2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:1300–1303.

- Sutton B, Ottomanelli L, Njoh E, Barnett S, Goetz L. The impact of social support at home on health-related quality of life among veterans with spinal cord injury participating in a supported employment program. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:1741–1747.

- Saunders LL, Krause JS, Saladin M, Carpenter MJ. Prevalence of cigarette smoking and attempts to quit in a population-based cohort with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2015;53:641–645.

- Guggenheimer J, Moore PA. Xerostomia: etiology, recognition and treatment. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:61–69.

- American Dental Association. Xerostomia (Dry Mouth). Available at: ada.org/en/member-center/oral-health-topics/xerostomia. Accessed January 26, 2022.

- Smith R. Mouth stick design for the client with spinal cord injury. Am J Occup Ther. 1989;43:251–255.

- Sezer N, Akkuş S, Uğurlu FG. Chronic complications of spinal cord injury. World J Orthop. 2015;6:24–33.

- American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Spinal Cord Injury—Types of Injury, Diagnosis and Treatment. Available at: aans.org/. Accessed January 26, 2022.

- Held KS, Steward O, Blanc C, Lane TE. Impaired immune responses following spinal cord injury lead to reduced ability to control viral infection. Exp Neurol. 2010;226:242–253.

- Allen KJ, Leslie SW. Autonomic dysreflexia. StatPearls. Available at: ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482434/. Accessed January 26, 2022.

- Krassioukov A, Stillman M, Beck LA. A primary care provider’s guide to autonomic dysfunction following spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord InJ Rehabil. 2020;26:123–127.

- Tomassoni PJ, Campagnolo DI. Autonomic dysreflexia: one more way EMS can positively affect patient survival. JEMS. 2003;28:46–51.

- Masri R, Keller A. Chronic pain following spinal cord injury. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;760:74–88.

- Sidorov EV, Townson AF, Dvorak MF, Kwon BK, Steeves J, Krassioukov A. Orthostatic hypotension in the first month following acute spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2008;46:65–69.

- Krassioukov AV, Karlsson AK, Wecht JM, Wuermser LA, Mathias CJ, Marino RJ. Assessment of autonomic dysfunction following spinal cord injury: rationale for additions to International Standards for Neurological Assessment. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44:103.

- Mohan R, Asir VD, Shanmugapriyan, et al. Nitrous oxide as a conscious sedative in minor oral surgical procedure. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7(Suppl 1):S248–S250.

- Oliveira ACG, Neves ILI, Sacilotto L, et al. Is it safe for patients with cardiac channelopathies to undergo routine dental care? Experience from a single‐center study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8: e012361.

- American Dental Association. Hypertension. Available at: ada.org/en/member-center/oral-health-topics/hypertension. Accessed January 26, 2022.

- Godzieba A, Smektała T, Jędrzejewski M, Sporniak-Tutak K. Clinical assessment of the safe use local anaesthesia with vasoconstrictor agents in cardiovascular compromised patients:a systematic review. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:393–398.

- Anttila S, Knuuttila M, Ylöstalo P, Joukamaa M. Symptoms of depression and anxiety in relation to dental health behavior and self-perceived dental treatment need. Eur J Oral Sci. 2006;114:109–114. doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0722.2006.00334.x.

- VA Health Care. Nutrition and Spinal Cord Injury 101. Available at: nutrition.va.gov/docs/UpdatedPatientEd/NutritionandSCI01-15.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2022.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. February 2022;20(2):39-42.