FTWITTY/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

FTWITTY/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Improve the Oral Health of Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder

While the research is mixed on whether this population is at increased risk for dental caries, dental hygienists are well-positioned to help these patients maintain their oral health.

This course was published in the February 2022 issue and expires February 2025. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the clinical manifestations of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and how it is diagnosed.

- Discuss the literature describing the association between ASD and dental caries.

- Describe treatment strategies to improve the oral health of patients with ASD.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by persistent impairment in social communication and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior and interest.1 The global occurrence of ASD is approximately 1%, while in the United States, about one in 44 individuals is diagnosed with ASD, most frequently during childhood.2,3 The age of diagnosis can vary, but 2 years is typically the age at which most diagnoses are made. Boys are four times more likely to be affected by ASD than girls.2

Characteristics of ASD include difficulty communicating and relating with others, impaired social interaction, and repetitive behaviors.4 Children with ASD may also display abnormal emotional and linguistic development, intellectual disability, and sensory perception problems.5,6 Early signs and symptoms may include absence of speech, language and other developmental delays, and lack of eye contact.6 Among those diagnosed after age 8, the signs and symptoms may also include hand flapping, extreme tantrums or outbursts, self-injurious behavior, and head banging.7

Some evidence shows that genetics play a role in the etiology of ASD.8,9 Studies have shown that up to 40% of ASD cases present with genetic aberrations.10 Environmental factors may also increase the risk of ASD. These include both exogenous factors, such as maternal exposure to tobacco and alcohol, and endogenous factors, including advanced parental age at conception, oxidative stress, or mitochondrial dysfunction.9,11 Some evidence suggests that maternal stress may contribute to an increased occurrence of ASD traits.9–11

Obtaining a Diagnosis

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) is the current standard used for diagnosis of all categories of ASD. After the American Psychiatric Association (APA) adopted a new standard for ASD in the DSM-5 criteria in 2013, a patient diagnosed with any of the four following conditions: autistic disorder, Asperger syndrome, pervasive developmental disorder (PDD), and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) are now diagnosed under the umbrella of ASD.12 Previously, ASD was deemed more clinically severe than PDD-NOS.13 On the other hand, some disorders previously diagnosed within the spectrum are no longer included in the DSM-5 diagnosis of ASD. For instance, social communication disorder (SCD), which is the absence of both verbal and nonverbal abilities to form social connections, is now classified separately from ASD.

When ASD is first suspected by parents/caregivers or primary healthcare providers, an initial screening exam is completed that includes both a patient and provider questionnaire along with a physical examination. If ASD is tentatively diagnosed during the screening exam, the patient will be referred to a specialist who will perform further testing to confirm the diagnosis. This comprehensive testing typically involves a series of both physical and mental assessments and may include genetic testing as well. Specific tests and diagnostic instruments are approved by the American Academy of Pediatrics and APA to confirm a diagnosis and reduce the likelihood of misdiagnosis, including Ages and Stages Questionnaire, Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales, Parents Evaluation of Developmental Status, Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, and the Screening Tool for Autism in Toddlers and Young Children.6,11,12

Problems with social interaction, attention deficit, and executive functioning frequently affect the lives of people with ASD. These issues can make caregiving by family members, educators, and healthcare providers challenging.14,15 One study suggests that—due to sensory, motor, and cognitive deficiencies—individuals with ASD are twice as likely to lack essential oral healthcare than those without developmental disabilities.16 As a result of these barriers, individuals with ASD may be at an increased risk of developing dental caries.17,18

Autism Spectrum Disorder and Dental Caries

Dental caries is the most common chronic disease of childhood, impacting 45.8% of those between the ages of 6 and 19 in the United States.1,19 Nine out of 10 US adults (ages 19 to 64) also have experienced caries in their permanent teeth.1 These high rates of decay emphasize the importance of early intervention, prevention, and treatment to promote optimal oral health. Some studies suggest that adults and children with ASD have a higher prevalence of dental caries, malocclusion, enamel hypoplasia, gingivitis, and periodontal diseases.4 Other studies, however, show that patients with ASD experience a similar or even lower caries prevalence than patients without ASD. This variation may be the result of differences on how various studies score caries prevalence, demographics of the population studied (such as age and gender), oral hygiene abilities, diet, and access to professional dental care.20–23

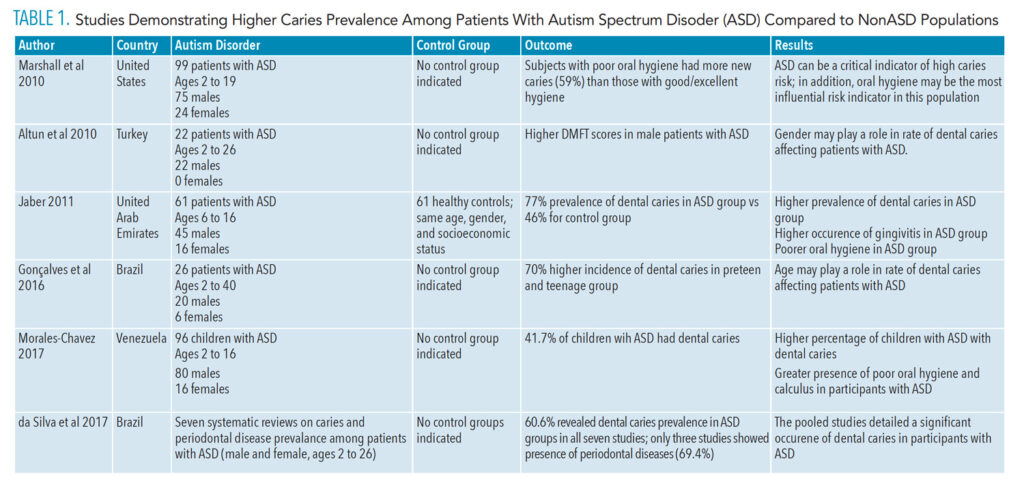

While inconsistencies exist in ascertaining caries prevalence among those with ASD, a number of studies focused on children, adolescents, and young adults.24,25 For example, in 2016, Gonçalves et al26 concluded that their preteen to teenage group of subjects with ASD showed a higher incidence of dental caries, averaging 70%. Other studies found that children and young adults with ASD were at high risk for tooth decay.27,28 Table 1 details additional studies that show a higher prevalence of caries in those with ASD.

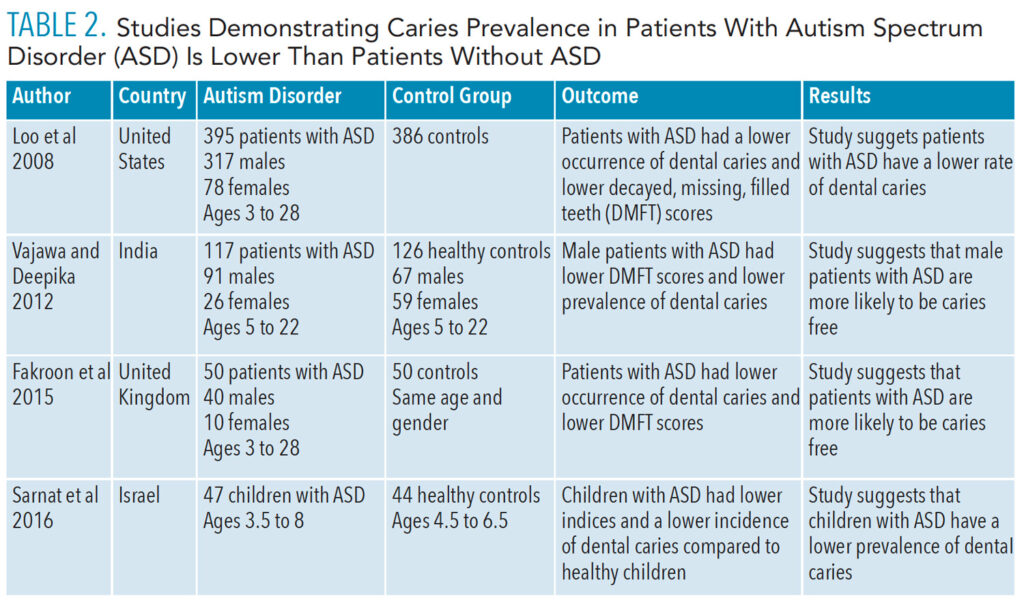

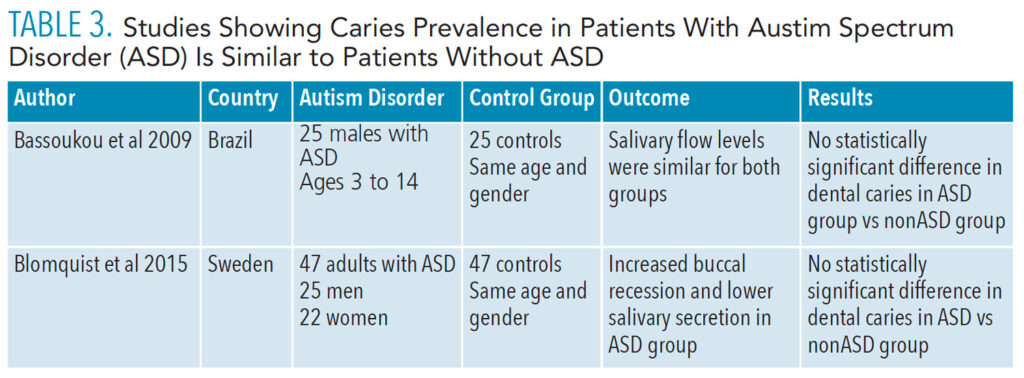

Some studies revealed lower rates of dental caries in children with ASD. In 2008, Loo et al29 observed significantly lower rates of caries in children ages 8 to 12 with ASD compared to children of the same age without ASD. Table 2 explores additional studies demonstrating a lower prevalence of dental caries in patients with ASD compared to nonASD populations. Table 3 shows studies that observed no difference in dental caries prevalence between ASD and nonASD populations. The inconsistencies in these studies reveal the need for further research with larger population groups.

Role of the Dental Hygienist in Caries Prevention

Patients with ASD may avoid dental treatment due to sensory processing deficits that can create anxiety, often leading to uncooperative behavior during the dental appointment.30,31 Reducing anxiety by desensitization and implementing specific treatment strategies prior to and during dental appointments are effective in patients with ASD.32,33 By facilitating the provision of dental care for this patient population in traditional private dental practices, the burden of seeking treatment under general anesthesia or hospital-based providers is eased. Dental hygienists play an important role in this process and help to significantly improve oral hygiene and reduce caries incidence.

Dental hygienists can improve oral healthcare for patients with ASD by providing the following:

- Verbal preparation for the patient and parent/caregiver prior to treatment

- Firm deep touch rather than light touch

- Reclining the dental chair prior to patient seating

- Dark glasses for the patient to wear to block out bright lights

- Head phones to decrease the noise associated with dental care

- Various textures and tastes in prophylaxis pastes

- Weighted blanket to provide comfort

- Management of certain dental tools and practices to address needs of individual patients34

Effective communication with patients with ASD and their parents/caregivers is critical to supporting oral health and reducing caries risk. Dental hygienists can help this patient population address risks caused by diet, functional habits, and the presence of xerostomia due to medication usage.4 For instance, behavioral and educational interventions can be introduced to reduce the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages.35 In addition, materials, such as pamphlets, posters, website links, books, and videos, can be recommended to patients with ASD and their caregivers. Pretreatment desensitization techniques are also available on smartphone and tablet apps that help patients with ASD and their parents/caregivers be well prepared for the dental office experience.30

Oral hygiene instruction is imperative for improving the oral health of patients with ASD. Caries risk assessment tools, such as those developed by the American Dental Association and the University of California San Francisco School of Dentistry (caries management by risk assessment, or CAMBRA), can be instrumental in preventing decay among patients with ASD.28

Educating Providers

As the incidence of ASD continues to increase, all oral health professionals should become educated on treatment strategies for this population beginning in dental and dental hygiene schools. Dental hygiene programs should incorporate didactic, clinical, and simulation-based content into their curriculum in order to better prepare students to effectively address patient needs, including those with ASD. Dao et al36 found that much improvement is needed in the application and delivery of education on treating patients with special needs, especially in undergraduate dental education programs. In 2020, the Commission on Dental Accreditation began requiring all undergraduate dental hygiene programs to provide evidence of competency in providing dental hygiene care for patients with special needs.37,38

As more dental hygiene programs train students to treat patients with special needs, including ASD, more dental hygienists working in clinical practice will be prepared to provide care to these populations.

Conclusions

While it remains uncertain whether those with ASD are at higher risk for dental caries, it is clear that oral health professionals are key to helping these patients maintain their oral health. Clinicians should seek further education to support their efforts at ensuring professional care is feasible for this patient population and to help them most effectively educate patients and their caregivers on strategies to improve and maintain oral health for a lifetime.

References

- Shi B, Wu W, Dai M, et al. Cognitive, language and behavioral outcomes in children with autism spectrum disorders exposed to early comprehensive treatment models: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:1.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Autism. Available at: cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html. Accessed January 25, 2022.

- Autism Speaks. What Is Autism? Available at: autismspeaks.org/what-autism. Accessed January 25, 2022.

- Jaber MA. Dental caries experience, oral health status and treatment needs of dental patients with autism. J Appl Oral Sci. 2011;19:212–217.

- Bartolome-Villar B, Mourelle-Martinez MR, Dieguez-Perez M, Nova-Garcia MJ. Incidence of oral health in pediatric patients with disabilities: sensory disorder and autism spectrum disorder. Systematic review II. J Clin Exp Dent. 2016;8:e344–e351.

- DePalma AC, Raposa KA. Building bridges: dental care for patients with autism. Available at: pathfindersforautism.org/docs/BuildingBridges1.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2022.

- Lyall K, Croen L, Daniels J, et al. The changing epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38;81–102.

- Sanchack KE, Thomas CA. Autism spectrum disorder: primary care principles. Am Fam Phys. 2016;94:972–979.

- Siu MT, Weksberg R. Epigenetics of autism spectrum disorder. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;978:63–90.

- Jeste SS, Geschwind DH. Disentangling the heterogeneity of autism spectrum disorder through genetic findings. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:74–81.

- Chaste P, Leboyer M. Autism risk factors: Genes, environment, and gene-environment interactions. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2012;14:281–292.

- Lord C, Bishop SL. Recent advances in autism research as reflected in DSM-5 criteria for autism spectrum disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2015;11:53–70.

- Zhang Y, Lin L, Liu J, Lu J. Dental caries status in autistic children: a meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50:1249–1257.

- Topal Z, Samurcu ND, Tufan AE, Semerci B. Social communication disorder: a narrative review on current insights. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;14:2039–2046.

- Cooper M, Martin J, Langley K, Hamshere M, Thapar A. Autistic traits in children with ADHD index and clinical and cognitive problems. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23:23–24.

- Onol S, Kirzioglu Z. Evaluation of oral health status and influential factors in children with autism. Niger J Clin Pract. 2018;21:429–435.

- Pi X, Liu C, Li Z, Guo H, Jiang H, Du M. A meta-analysis of oral health status of children with autism. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2020;44:1–7.

- Stein LI, Leah I, Polido JC, Najera SO, Cermak SA. Oral care experiences and challenges in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatr Dent. 2012;34:387–391.

- Chi DL, Scott JM. Added sugar and dental caries in children: a scientific update. Dent Clin North Am. 2019;63:17–33.

- Bassoukou IH, Nicolau J, Dos SM. Saliva flow rate, buffer capacity, and pH of autistic individuals. Clin Oral Investig. 2009;1:23–27.

- Latifi-Xhemajli B, Begzati A, Kutlovci T, Ahmeti D. Dental health status of children and adolescents with special health care needs. J Int Dent Med Res. 2018;11:945–949.

- Vajawat M, Deppika PC. Comparative evaluation of oral hygiene practices and oral health status in autistic and normal individuals. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2012;2:58–63.

- Sarnat H, Samuel E, Ashkenazi-Alfasi N, Peretz B. Oral Health Characteristics of preschool children with autistic syndrome disorder. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2016;40:1:21–25.

- Fakroon S, Arheiam A, Omar S. Dental caries experience and periodontal treatment needs of children with autism spectrum disorder. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2015;16:205–209.

- Morales-Chavez MC. Oral health assessment of a group of children with autism disorder. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2017;4:147–150.

- Gonçalves LT, Gonçalves FY, Noguera BM, et al. Conditions for oral health in patients with autism. Int J Odontostomat. 2016;10:93–97.

- da Silva SN, Gimenez T, Souza RC, et al. Oral health status of children and young adults with autism spectrum disorders: systemic review and meta-analysis. Int J Pediatr Dent. 2017;27:388–398.

- Marshall J, Shellar B, Manci L. Caries-risk assessment and caries status of children with autism. Pediatr Dent. 2010;32:69–75.

- Loo CY, Graham RM, Hughes CV. The caries experience and behavior of dental patients with autism spectrum disorder. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:1518–1524.

- Elmore JL, Bruhn AM, Bobzien JL. Interventions for the reduction of dental anxiety and corresponding behavioral deficits in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Dent Hyg. 2016;90:111–120.

- Capozza LE, Bimstein E. Preferences of parents of children with autism spectrum disorder concerning oral health and dental treatment. Pediatr Dent. 2012;34:480–484.

- Kuhaneck HM, Chisolm EC. Improving dental visits for individuals with autism spectrum disorders through an understanding of sensory processing. Spec Care Dent. 2012;32:229–233.

- Cermak SA, Duker LI, Williams ME, Dawson ME, Lane CJ, Polido JC. Sensory adapted dental environments to enhance oral care for children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled pilot study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45:2876–2888.

- Burgette JM, Rezaie A. Association between autism spectrum disorder and caregiver reported dental caries in children. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2020;5:254–261.

- Zoellner JM, Hedrick VE, You W, et al. Effects of a behavioral and health literacy intervention to reduce sugar-sweetened bevarages: a randomized—controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:38.

- Dao LP, Zwetchkenbaum S, Inglehart MR, Habil P. General dentists and special needs patients: does dental education matter? J Dent Educ. 2005;69:1107–1115.

- Commission on Dental Accreditation. Accreditation Standards for Dental Hygiene Education Programs Standards. Available at: https://coda.ada.org/~/media/CODA/Files/dental_hygiene_standards.pdf?la=en. Accessed January 24, 2022.

- Keselyak NT, Simmer-Beck M, Bray KK, Gadbury-Amyot CC. Evaluation of an academic service-learning course on special needs patients for dental: a qualitative study. J Dent Educ. 2006;71:378–392.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. February 2022;20(2):35-38.