The Benefits of Xylitol

The positive health effects of this sugar alcohol extend beyond the oral cavity.

This course was published in the December 2013 issue and expires 12/31/16. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define xylitol and its genesis.

- Discuss the difference between xylitol and sugar.

- List the oral and systemic health benefits of xylitol use.

- Identify xylitol dosage recommendations.

XYLITOL DEFINED

Xylitol is a naturally occurring sweetener found in a variety of fruits (berries), vegetables (cauliflower, mushrooms), and trees (birch wood). It is a five-carbon sugar polyol (alcohol), with approximately 40% fewer calories than table sugar.1 As a crystalline carbohydrate resembling sugar, xylitol produces a sweet, slightly minty taste. The human body naturally produces xylitol by metabolizing carbohydrates in the stomach. Due to the site of metabolization, however, the oral cavity is exposed to little of the xylitol created (between 5g and 10g).2

GLOBAL ACCEPTANCE OF THE NATURAL SWEETENER

Xylitol was discovered in Germany in 1890; however, it did not receive much attention until 1970, when studies evaluating the effectiveness of xylitol on the reduction of dental plaque were conducted in Turku, Finland. Completed with the support of the World Health Organization, the so-called Turku sugar studies looked at the differences between subjects who consumed diets in which sucrose was completely replaced with either xylitol or fructose.3 Results showed a significant reduction in caries activity among those participants on the xylitol diet. A subsequent study on xylitol conducted at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor revealed that the naturally occurring sugar reduced levels of Streptococcus mutans.4

In 1963, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved xylitol for “special dietary purposes,” and the natural sweetener is now categorized as “generally recognized as safe.”5 In addition, the use of xylitol in caries prevention is supported by the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD).6

The US Army Dental Command uses xylitol in its health promotion program, which is focused on the prevention of oral diseases. 7 The program includes the initiative “Look for Xylitol First,” which promotes the oral health benefits and proper use of xylitol. Deployed soldiers are also supplied with xylitol chewing gum in their food rations.7

American dental professionals are only beginning to acquire the knowledge and resources necessary to make widespread recommendations, as well as to promote xylitol as an oral health aid. The Arizona, Hawaii, and Kentucky dental hygienists’ associations were the first to endorse the natural sweetener in 2008.8 California, Texas, Wisconsin, Florida, Pennsylvania, Nebraska, Nevada, New York, and Maine dental hygienists’ associations have since made formal efforts toward advocating and educating patients about xylitol benefits and usage.8

More than 35 countries have approved xylitol for use in food, oral health products (dentifrice, mouthrinse, candies, and gum), and pharmaceuticals.6 Finland’s “Smart Habits” campaign was the first program designed to reduce the incidence of dental caries in children through the use of xylitol.9 The Finnish, Swedish, and British dental associations have endorsed the use of xylitol since 1988.8 In Europe, Asia, and Canada, xylitol is recognized for its benefits and sold extensively.7

THE PREFERRED SUGAR RUSH

Xylitol is not only all-natural, but it has fewer calories than fructose, glucose, and sucrose.1 Fructose and glucose are six-carbon monosaccharide units, sucrose is composed of glucose and fructose units, and xylitol is a sugar alcohol. Sucrose, fructose, and glucose are food sources for S. mutans.2 After the bacteria ingest these sugars, the excretions produce plaque biofilm that may lead to dental caries if not mechanically removed. Xylitol, however, does not bond with sugars due to its five-carbon structure.2 Rather than provide nutrients to S. mutans, xylitol blocks the bacteria’s harmful effects and protects the surface of the tooth—even interfering with the metabolism of the bacteria when transported into a cell. The S. mutans bind to protein instead of sugar, preventing them from attaching to additional sugars.2

This leads to less dental plaque accumulation, as the harmful bacteria cannot stick to the teeth. The number of S. mutans in the oral cavity is significantly reduced, which decreases acid production and raises pH levels.5 Sugar raises blood pressure; increases the risk of heart disease, diabetes, and obesity; and depletes the body of vital minerals and vitamins—making xylitol an attractive alternative.2

ORAL HEALTH BENEFITS

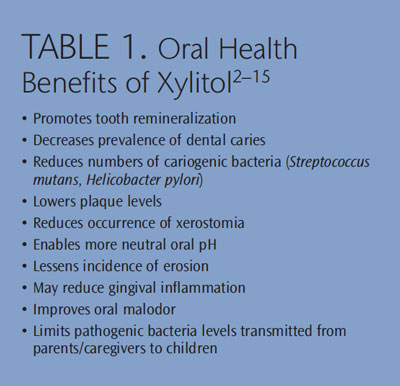

There are several clinically significant studies demonstrating the oral health benefits of xylitol (Table 1 provides a summary).2–15 Best known for reducing dental caries, xylitol also enhances salivary flow, which promotes pH levels by raising pH alkalinity.2,5 By reducing acid in the mouth, the risk of tooth enamel erosion is decreased.9 The oral health of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease or bulimia nervosa may benefit from this pH neutralizer, which reduces the acid attacks that cause tooth erosion.16 Additionally, xylitol promotes remineralization of early lesions on tooth enamel.2

A small body of research has found that xylitol may reduce gingival inflammation, which could lead to a decrease in the oral manifestations of periodontal diseases.1,17 Periodontal diseases have been associated with Helicobacter pylori in previous studies,and xylitol may reduce their numbers in the oral cavity.1 Oral malodor— caused by xerostomia, smoking, and/or poor salivary flow—may also be decreased through xylitol’s ability to increase salivary flow.1,18

Xylitol may exert its most significant benefits in the prevention and treatment of early childhood caries (ECC). The US Surgeon General’s Report notes that ECC is one of the most serious public health threats facing the nation today.19 This disease affects young children and manifests as severe decay of multiple teeth.14 Data suggest ECC is the most common transmittable childhood disease, affecting as many as 41% of American children.13

A research study demonstrated that erupting teeth benefit the most from exposure to xylitol.20 This is because the mouths of newborn children lack bacteria and acquire pathogens through transmission of saliva from parents/ caregivers.13 Children of mothers with high levels of S. mutans are at increased risk of ECC. By using xylitol, parents/caregivers can reduce bacteria levels in their own mouths, decreasing the transmission of S. mutans to the child.8,15

ADDITIONAL USES

Beyond dentistry, xylitol delivers many health and nutritional benefits (Table 2).21–29 Studies are currently being conducted on the efficacy of xylitol in increasing bone density, which would benefit individuals with osteoporosis or osteopenia. These metabolic diseases decrease bone density through tissue deterioration—increasing the risk of break or fracture.1,21 A 1994 Finnish study found that xylitol was effective at increasing bone density in rats.30 Xylitol’s possible role in increasing bone density would also make its use beneficial for additional populations that experience low bone density, including older adults and individuals with anorexia nervosa.

Patients with diabetes—a chronic metabolic disorder in which the body either has a deficiency in insulin production or the body does not use the hormone appropriately—may also benefit from xylitol use.26 Insulin is a necessary hormone produced in the pancreas that the body uses to transform nutrients into energy—which enables proper metastasis of carbohydrates, proteins, andfats. In dividuals with diabetes can experience dangerous increases in blood glucose levels, or hyperglycemia.26 Use of xylitol is recommended for patients with diabetes, as the natural sweetener does not cause changes in blood glucose/insulin, reducing the incidence of hyperglycemia. This is because xylitol is slowly digested by the body as a carbohydrate, remaining “out of the insulin loop.”7

Xylitol does not require insulin to enter cells, making it is an excellent low-calorie and low-carbohydrate dietary option.22 Furthermore, the antiketogenic properties of xylitol inhibit types of bacterial growth,22 which is advantageous for individuals with diabetes who often experience delayed wound healing.

Additional medical uses and benefits of xylitol include: the stimulation of mixed-function oxidase, which reduces the incidence of liver and bile duct issues; antiulcer activity; prevention of adrenocortical suppression, which may occur during steroid therapy; increased absorption of vitamin B and body protein; and acts as an anabolic dietary substance.20–29

Patients with Sjögren’s syndrome—an autoimmune rheumatic disease characterized by lethargy, dry eyes, xerostomia, and increased risk of dental caries and oral candidiasis—may also benefit from xylitol use.12 Consumption of xylitol among this patient population may yield benefits such as increased salivary flow and prevention of dental caries.5,6,18 In patients with Meniere’s disease—a disorder affecting the inner ear that causes dizziness, hearing loss, and tinnitus (ringing in the ears)—xylitol has been shown to increase auditory threshold values.5,16 The use of xylitol as prophylaxis for treating acute middle ear infections or acute otitis media—a common illness among children age 6 and younger—has been shown to be successful.5

A decrease in sinus, oropharyngeal, and nasal infections has also been documented, along with improvements for patients experiencing pneumonia, cystic fibrosis, and lung infections.29 Xylitol lowers the concentration of salt lining the lungs, thereby increasing the body’s ability to fight infections.29 Xylitol may also reduce H. pylori levels, a leading cause of gastric ulcers, duodenal ulcers, and a risk factor for stomach cancer.28

POSSIBLE SIDE EFFECTS

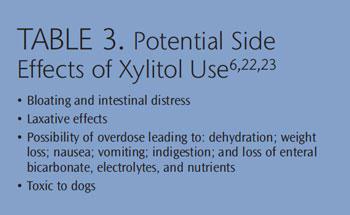

Xylitol has few contraindications, but it can exert negative side effects (Table 3).6,22,23 Only partially absorbed by the liver, the other two-thirds of this sweetener are broken down and eliminated through the intestinal tract.6 When high levels of xylitol are consumed too rapidly, bloating and intestinal distress may occur.23

Although hardly a well-known fact, many low-carbohydrate foods, such as specially made breads, desserts, and candies, contain xylitol. While the consumption of these products may provide inadvertent oral and systemic health benefits,7 it may be difficult for patients to gauge how much xylitol they are consuming. The FDA does not require the inclusion of xylitol as an active ingredient on food labels.7

Xylitol overdose can cause diarrhea, dehydration, and weight loss, as well as gastrointestinal pain, nausea, vomiting, indigestion, and enteral bicarbonate loss.10 Electrolytes, nutrients, and water are lost after excessive dehydration, which can lead to improper functioning of body systems. Xylitol is also extremely toxic to dogs, so all products containing xylitol should be kept out of their reach.21

DOSING FOR DENTAL BENEFITS

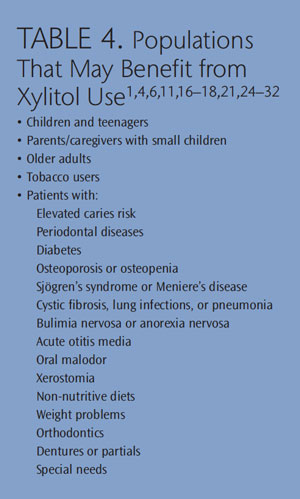

Many patients may benefit from a personalized self-care regimen that includes the use of xylitol products (Table 4).1,4,6,11,16–18,21,24–32 Xylitol promotes both dental and overall health, though the frequency of its use and recommended dosage should be given careful consideration. Recommendations of delivery or product type should be given to patients on a case-by-case basis, taking into account age, current and past dental health status, systemic health considerations, and patient preference. Affordability and easy access have helped promote the use of this natural sweetener and have encouraged its widespread adoption.

When educating patients on oral health aids, dental professionals need to discuss not only the benefits of an adjunct product but also potential side effects; recommended frequency of use; and correct dosage levels. Studies vary on the appropriate dosage level for xylitol and the maximum recommended dose for children and adults. On average, 45 g of xylitol per day can be tolerated by children without negative side effects, while adults can safely consume 150g to 200g daily.6 The AAPD recommends 3g to 8g of xylitol syrup or wipes used throughout the day for children age 3 and younger.6 Many sources state” strive for five,” or consuming five servings per day, when recommending correct xylitol frequency.6 Patients at high caries risk should use xylitol products after snacking.6

XYLITOL DELIVERY MECHANISMS

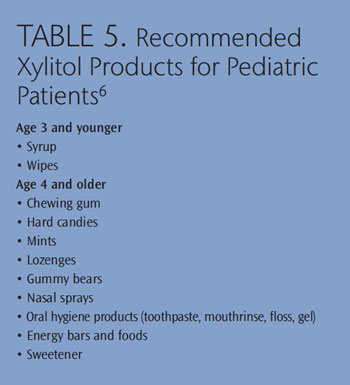

The most popular approach for delivering xylitol to the oral cavity is chewing gum,8 though many products contain this all-natural sweetener. Mints and hard candies may also include xylitol, with studies demonstrating that these modalities are as effective as chewing gum.6 The AAPD states that chewing gum, mints, and hard candies are contraindicated for children age 3 and younger due to the increased risk of choking and instead recommends the use of xylitol syrups or wipes (Table 5).6

A study investigating the daily consumption of 8 g of xylitol syrup among 15-month-old to 25-month-old children with ECC found that the incidence of ECC was reduced by up to 70%.33 The AAPD recommends that children age 4 and older use xylitol products that are age appropriate, including chewing gum, mints, candies, lozenges, certain foods, energy bars, and even gummy bears.6 When issuing recommendations, the delivery mechanism must be tailored to each patient’s individual needs.

A study investigating the daily consumption of 8 g of xylitol syrup among 15-month-old to 25-month-old children with ECC found that the incidence of ECC was reduced by up to 70%.33 The AAPD recommends that children age 4 and older use xylitol products that are age appropriate, including chewing gum, mints, candies, lozenges, certain foods, energy bars, and even gummy bears.6 When issuing recommendations, the delivery mechanism must be tailored to each patient’s individual needs.

When speaking to patients about xylitol-containing products, clinicians must stress that xylitol should appear first in the list of ingredients in order to maximize its effectiveness. The US Army’s “Look for Xylitol First” program asserts that xylitol must appear before “gum base” on the gum wrapper in order to be effective.7

Nasal sprays are another modality to deliver xylitol’s benefits. The use of xylitol to decrease sinus, oropharyngeal, and nasal infections has been documented.29 Toothpaste, mouth rinse, floss, and gels also offer increased xylitol intake. Dentifrices containing 10% xylitol are effective in reducing dental caries and S. mutans.6 The diversity of xylitol-containing products may boost compliance by offering patients a variety of options, and supports the recommendation of obtaining at least five exposures to xylitol per day.6

Products with therapeutic doses of xylitol may be purchased online or at select retail stores.6 Several companies offer patient product samples, which can be given out at dental appointments. Brochures about xylitol and its benefits also serve as an excellent patient education tool and should provide advice on where to purchase xylitol products.

CONCLUSION

Xylitol is an all-natural, health-promoting ingredient used extensively in many countries with great success. Proven to deliver significant dental and overall health benefits, xylitol most notably decreases the presence of S. mutans associated with dental caries. Proper dosage levels, delivery vehicles, frequency, potential benefits, and negative side effects must be explained thoroughly to encourage patients to adopt it use, as xylitol is still a novel product in the US. Dental hygienists can use xylitol to partner with patients to help them improve their oral health.

References

- Ward D. Xylitol—cavity fighting sweetener a possible solution for osteoporosis. Townsend Letter for Doctors and Patients. 2002:80.

- Touger-Decker R, van Loveren C. Sugars and dental caries. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:8815–8925.

- Scheinin A, Mäkinen KK, Ylitalo K. Turku sugar studies. V. Final report on the effect of sucrose, fructose and xylitol diets on the caries incidence in man. Acta Odontol Scand. 1976;34:179–216.

- Mäkinen KK, Söderling E, Isokangas P, Tenovuo J, Tiekso J. Oral biochemical status and depression of Streptococcus mutans in children during 24- to 36-month use of xylitol chewing gum. Caries Res. 1989;23:261–267.

- Mäkinen KK. The rocky road of xylitol to its clinical application. J Dent Res. 2000;79:1352–1355.

- Guideline on xylitol use in caries prevention. Handbook of Pediatric Dentistry. 4th ed. Chicago: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2011:166–169.

- Richter P, Chaffin J. Army’s “look for xylitol first” program. Dent Assist. 2004;73:38–40.

- Clark S. Wonders of xylitol. Available at:

www.rdhmag.com/articles/print/volume-31/issue-4/features/wonders-of-xylitol.html. Accessed December 3, 2013. - Nordblad A, Suominen-Taipale L, Murtomaa H, Vartiainen E, Koskela K. Smart Habit Xylitol campaign, a new approach in oral health promotion. Community Dent Health.1995;12:230–234.

- Nadimi H, Wesamaa H, Janket SJ, Bollu P, Meurman JH. Are sugar-free confections really beneficial for dental health? Br Dent J. 2011;211:E15.

- Ly KA, Riedy CA, Milgrom P, Rothen M, Roberts MC, Zhou L. Xylitol gummy bear snacks: a school-based randomized clinical trial. BMC Oral Health. 2008;8:20.

- Manski MC, Parker ME. Early childhood caries: knowledge, attitudes, and practice behaviors of Maryland dental hygienists. J Dent Hyg. 2010;84:190–195.

- Marrs JA, Trumbley S, Malik G. Early childhood caries: determining the risk factors and assessing the prevention strategies for nursing intervention. Pediatr Nurs. 2011;37:9–15.

- Arora A, Scott JA, Bhole S, Do L, Schwarz E, Blinkhorn AS. Early childhood feeding practices and dental caries in preschool children: a multicentre birth cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:28.

- American Dental Association. Oral health topics: Early childhood tooth decay (baby bottle tooth decay). Available at: www.ada.org/3109.aspx. Accessed November 21, 2013.

- Danhauer JL, Johnson CE, Rotan SN, Snelson TA, Stockwell JS. National survey of pediatricians’ opinions about and practices for acute otitis media and xylitol use. J Am Acad Audiol. 2010;21:329–346.

- Steinberg LM, Odusola F, Mandel ID. Remineralizing potential, antiplaque and antigingivitis effects of xylitol and sorbitol sweetened chewing gum. Clin Prev Dent. 1992;14:31–34.

- Armstrong BL, Sensat ML, Stoltenberg JL. Halitosis: a review of current literature. J Dent Hyg. 2010;84:65–74.

- Satcher DS. Surgeon General’s report on oral health. Public Health Rep. 2000;115:489–490.

- Hujoel PP, Mäkinen KK, Bennett CA, et al. The optimum time to initiate habitual xylitol gumchewing for obtaining long-term caries prevention. J Dent Res. 1999;78:797–803.

- Sato H, Ide Y, Nasu M, Numabe Y. The effects of oral xylitol administration on bone density in rat femur. Odontology. 2011;99:28–33.

- Peterson ME. Xylitol. Top Companion Anim Med. 2013;28:18–20.

- Wille D, Hauri-Hohl M, Vonbach P, Tomaske M, Padden B, Bernet V. Too much of too little: xylitol, an unusual trigger of a chronic metabolic hyperchloremia acidosis. Eur J Pediatr. 2010; 169:1549–1551.

- Mathews SA, Kurien BT, Scofield RH. Oral manifestations of Sjögren’s syndrome. J Dent Res. 2008;87:308–318.

- Vassiliou A, Vlastarakos PV, Maragoudakis P, Candiloros D, Nikolopoulous TP. Meniere’s disease: Still a mystery disease with difficult differential diagnosis. Ann Indian Acad Neruol. 2011;14:12–18.

- Bascones-Martinez A, Matesanz-Perez P, Escribano-Bermejo M, Gonzalez-Moles MA, Bascones-Ilundain J, Meurman JH. Periodontal disease and diabetes—review of the literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2011;16:e722–729.

- Deshmukh J, Basnaker M, Kumar Kulkarni V, Katti G. Periodontal disease and diabetes—a two way street dual highway? People’s Journal of Scientific Research. 2011;4(2):65–71.

- Roszczenko P, Radomska KA, Wywial E, Collet JF, Jagusztyn-Krynicka EK. A novel insight into the oxidreductase activity of Helicobacter pylori HP0231 protein. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46563.

- Medscape. Simple sugar may prevent lung infections in CF patients. Available at: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/412179. Accessed November 22, 2013.

- Svanberg M, Knuuttila M. Dietary xylitol prevents ovariectomy induced changes of bone inorganic fraction in rats. Bone Miner. 1994;26:81–88.

- Blevins JY. Oral health care for hospitalized children. Pediatr Nurs. 2011;37:229–235.

- Honkala E, Honkala S, Shyama M, Al-Mutawa SA. Field trial on caries prevention with xylitol candies among disabled school students. Caries Res. 2006;40:508–513.

- Milgrom P, Ly KA, Tut OK, et al. Xylitol pediatric topical oral syrup to prevent dental caries: a double-blind randomized clinical trial of efficacy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:601–607.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. December 2013;11(12):64–68.