Understand the World of Social Media

Adhering to ethical principles is integral to maintaining professionalism while utilizing the many types of online platforms available today.

This course was published in the December 2013 issue and expires December 2016. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define social media and social media types.

- Discuss the importance of professionalism and ethics as they relate to clinicians’ online activities.

- Review the provisions of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act in relationship to social media.

- List recommendations for protecting patient information and limiting clinicians’ liability when using social media.

The role of the dental hygienist goes far beyond the walls of the dental practice. This concept is nothing new to many oral health professionals, but it begs a question—what happens when those walls fall away, requiring clinicians to bridge the standards of ethical principles, sound judgment, and good moral character to the world of social media? Connecting standards of the clinical world to social media is relatively straightforward. By gaining greater knowledge and becoming aware of how these two worlds intersect, oral health professionals can attain a clearer perspective on the benefits and risks of using social media in both professional and personal settings. Social media is a new world worth understanding, but clinicians must learn how to manage and maintain an online presence so that potential pitfalls can be avoided.

DEFINING SOCIAL MEDIA

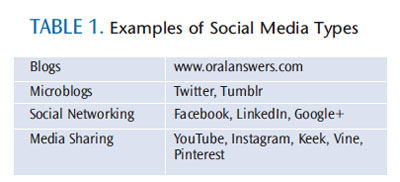

Social media is defined as forms of electronic communication through which users join online communities to share information, ideas, personal messages, and other content. Blogs, networking sites, and media sharing sites are all considered types of social media (see Table 1 and images for examples). Blogs are considered noninteractive journals that are frequently updated and intended for general public consumption,1 whereas microblogs allow users to interact but limit the file size, words, or characters of all posted content. Networking sites require participants to create personalized profiles, after which they can choose other “users/ friends/ followers,” who may then access their personal page. Members of these sites utilize their personal page to display and share photographs, videos, post messages, or have instant message (chat) conversations. Media sharing sites enable participants to share videos, music, and photographs.1 Most blogs, microblogs, social networking, and media sharing sites require users to register, while each type provides its members with varying levels of privacy.

The most popular social networking sites are Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, and Tumblr. As of November 2013, Facebook had 1.19 billion monthly users worldwide, and Twitter boasted 555 million global members.2,3 Instagram cites 150 million active users who have shared nearly 16 billion photos since its inception in 2010.4 The number of individuals who opt to communicate through these social media sites continues to grow daily, and it is safe to assume that both clinicians and patients are part of this dynamic. For this reason, many private dental practices in the United States have embraced social media as a marketing tool, utilizing the aforementioned sites to share promotions on products, services, discounts, and more.

GOLDEN STANDARDS

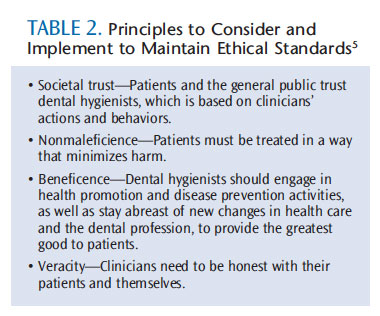

Oral health professionals who use social media must remember that the image projected through their online profile(s) should uphold the ethical and professional principles learned during dental hygiene school. A professional is an individual who maintains a set of qualities, such as integrity, honesty, knowledge, and skills, within his or her field. Dental hygienists, for example, should learn the American Dental Hygienists’ Association’s (ADHA) Professional Code of Ethics. This resource helps professionals achieve high levels of ethical consciousness and decision-making.5 According to the ADHA code, ethics is defined as the general standards of right and wrong that guide behavior within society.5 Ethical principles should be part of the decision-making process, even when using social media platforms. Table 2 lists the key principles that clinicians should consider daily to uphold high ethical standards.5

In addition to these ethical principles, ensuring patient confidentiality and privacy is of utmost importance. Standards of privacy are enforced through the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), which was established in 1996. Confidentiality means keeping patients’ protected health information (PHI) safe and private, including identifiable data (name, number, address, age, etc). While practice records can be updated or errors corrected, social media makes it easy to post a mistake that cannot be erased from the digital world. The error can lead to a breach of privacy, which could constitute a HIPAA violation. Civil and criminal penalties are direct results of HIPAA violations.

According to the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), a person who knowingly obtains or discloses individually identifiable health information in violation of the privacy rule may face a criminal penalty from $50,000 to $250,000 in fines, and up to 10 years imprisonment. Civil penalties range from $100 to $50,000 or more in fines, per violation.6 Known breaches in the HIPAA law should be reported to the HHS’ Office of Civil Rights. Oral health professionals can also face disciplinary actions from their state board of dental examiners—ranging from suspension to loss of license, based on the incident.

When clinicians lose sight of ethics and standards, an insensitive post shared via social media can result in HIPAA penalties. As a hypothetical example, a patient comes into a dental practice seeking treatment for a severe abscess. The patient’s face is extremely swollen, and no one in the office has ever seen anything like it. While the patient waits for the dentist, both the dental hygienist and dental assistant use their cell phones to take a picture—which they later post to their personal social media accounts, along with the message “No one should ever let this happen.”

In this extreme example, both clinicians shared the patient’s identifiable health information—which allows their followers to learn personal health information about the patient, including the office where the patient receives dental care, when he or she went to the dentist, and more. Though fictitious, this scenario has played out in real cases in the medical field, resulting in HIPAA violations and penalties for the clinician and his or her place of employment.

Omission of a name does not constitute proper deidentification of PHI. Posting any data that include age, gender, race, diagnosis, date of evaluation, treatment, or the use of specific photographs/videos (eg, before/after photographs of patients having surgery or any likeness of patients) may still allow readers to recognize a specific individual.7,8

Clinicians must remain apprised of HIPAA policies, especially when engaging in social media professionally or personally, and when patients of record are friends/followers. While it is not a HIPAA violation if patients decide to post sensitive data about themselves on a social media site,9 clinicians must refrain from doing so on personal or professional blogs, microblogs, networking, and media sharing sites without patient consent.10

Oral health professionals should also avoid editing comments or criticism posted on professional social media sites. Once the comment or criticism is changed by an entity that is covered by HIPAA, a violation can apply.9 Responding to these comments/criticism only identifies the individual as a patient of record. Likewise, it is best to avoid engaging in discussions related to dental care, treatment, or diagnosis on all social media sites—professional and personal. Ragan9 recommends that clinicians ask patients to call or visit the dental office to discuss their questions—exercising best practices by taking the conversation offline—to avoid releasing confidential patient information in the social media realm.

COMMUNICATION AND ONLINE IMAGE

One benefit of the Internet is that it allows messages to be sent and received within a matter of seconds. While instantaneous message transfer is gratifying, clinicians must focus on how words are perceived in the realm of cyber communication. Verbal communication to relay information is primarily used during face-to-face interactions. Through social media, however, typed messages are the main transport of information, with some patients becoming lost in translation of the message received.

Because social media eliminates verbal cues, the nonverbal aspects of one-on-one in-person conversations—such as facial expression and body language—are lost.11 For instance, a clinician might ask a patient about his/her attempt to stop smoking during a routine care appointment with “How are things going?” The patient responds “great” with a sad facial expression, to which the dental hygienist may follow with “What’s wrong?” The patient’s nonverbal cue not only implies that something is amiss, but it could also lead the clinician to believe that the patient is having trouble quitting. If the clinician had this same conversation online with a friend, however, the clinician would not be aware of possible challenges faced by the friend because of the absence of nonverbal cues—an important component of communication. Additionally, loss of nonverbal cues and facial expressions can cause social media followers or friends to misinterpret the message being relayed. Conversing via social media messaging also makes it difficult for followers to determine seriousness vs sarcasm.

Social media can foster feelings of invisibility and lack of concern for others, which can prompt individuals to say and do things they would never do in person.12,13 Ragan9 states that any actions and content posted online may negatively affect reputations among patients and colleagues, as well as individual careers, and that negative posts can undermine public trust in the profession. Leiker14 encourages clinicians who engage in this medium to simply pause before posting—each post that becomes public can be shared with patients, colleagues, and employers, following users for the entirety of their careers.

Everything shared on social media is permanent; once posted, it no longer belongs to the user. There is no way to control how far and wide messages, photos, or videos posted to social media sites will be disseminated—content can be reposted, retweeted, copied, and even changed many times over. In addition, any digital exposure can “live on” beyond its removal from the original website and continue to circulate in other venues.8 Pausing before posting is the key to avoiding regret. In fact, subpoenas can be issued requiring Internet service providers, social networking companies, and websites to produce Internet protocol addresses or email addresses that identify the source of the content.14 Kevin Pho, MD, follows two rules before posting content on social media. He first imagines how patients would perceive the post if they were to stumble across it. Then he asks himself a series of questions, including: would it make the patient cringe?; would it make the patient feel awkward during their next office visit?; and would this somehow compromise the patient-provider relationship?15 Checking one’s conscience before posting seems a worthwhile rule to apply when using social media.

The digital image of social media users is something that will not fade. Every digital media-based action taken, even a visit to a website without any real action, leaves a digital footprint that cannot be erased.16 Madden et al17 discovered that more than half of adult Internet users have used a search engine to track others’ digital footprints. Protecting that image should be important to all professionals, because it can serve as your first impression. In this regard, Madden et al17 found that 19% of adults searched for coworkers and professional colleagues, while 11% searched for information on potential hires, via the Internet. Oral health professionals must ensure that their digital footprint reflects professionalism, respectfulness, and trustworthiness.

PATIENT ENGAGEMENT

Social media is all about connection. Anyone who is interested in a user’s profile, or the messages he or she relays, can request to connect. These requests can come from family, friends, and even strangers. It should not come as a surprise that patients in the dental practice may request to follow their trusted clinicians. In fact, a recent medical survey found that 34% of practicing physicians received friend requests from patients.18 Oral health professionals should take a moment to contemplate the possible challenges and repercussions that could stem from bridging the gap between their professional and personal lives.

The literature is consistent: avoid accepting patients as friends/followers on personal social media sites. Online contact with patients or former patients blurs the distinction between a professional and personal relationship.19 Leiker14 suggests that clinicians keep their personal and professional content separate—moreover, if patients request to connect on social media, direct them to the practice’s professional page. The US Department of Veteran Affairs explains that boundaries create a safe space for the treatment and care of patients to occur, allowing them to trust, respect, and remain confident in their oral health providers.20

It is critical to consider several questions in relation to boundary setting. Clinicians should ask themselves how much they are willing to share and reveal to patients. Do they mind allowing patients to see personal pictures? Would they be uncomfortable if patients started to make comments or ask questions about their personal lives? And how would they feel if their patients no longer trusted their judgment based on a single image or message visible on their profile? Oral health professionals must be cognizant when interacting with patients in ways that could create awkward situations for both parties.20 Bosslet et al18 recommends that those who feel compelled to connect online with patients closely police their privacy status and profile content. This involves content that could be viewed as disrespectful, too intimate, or too contentious.14

SOCIAL MEDIA POLICIES IN THE DENTAL OFFICE

Sometime between the interview process and the job offer, clinicians should learn the basic rules and guidelines followed by the dental practice—including standards for social media use. Anderson and Isackson10 state that social media policies should be in place to avoid scrambling for a solution during a crisis.

Implementing social media policies within the dental practice can provide a clear understanding of the do’s and don’ts of online use. Statements within the policy should could cover topics on patient privacy/HIPAA and online behaviors that are forbidden, inappropriate, or impermissible under any circumstances.21 A social media policy can be a company’s first line of defense to mitigate risk for both employer and employee.22 Practice owners should not assume their workers know what social media pitfalls to avoid, especially if there has never been an open discussion. Rules should be established on whether oral health professionals are allowed to check their personal profiles on social media sites during work hours, in addition to establishing consequences if social media guidelines are broken. Clinicians who work in practices with a policy in place should familiarize themselves with the rules they are expected to know and follow. Do not be shy in asking for clarification on a policy that has already been established. Social media features change daily, and updates to the policy should be considered based on these developments.

Azark23 notes employers cannot demand that employees close their social networking sites. Additionally, several states have laws in place that prohibit employers from asking for users’ social media passwords. These laws, however, are not set in place for workers to become careless and irresponsible with the content they choose to put forth on social media. If an employer feels as though a breach of a patient’s privacy has occurred, or if he or she attains proof of online misconduct, the employee can be held liable for those actions. Posts shared via social media are not private and can be subpoenaed by a court of law if an investigation occurs.

For practices without social media policies, Azark23 recommends that the existing confidentiality policy be amended to include social media guidelines. This creation process is a great time for the practice to work as a team to decide what is important to include in such a policy. The team that creates the policy should comprise individuals who are knowledgeable of technology and social media, as well as those who are not.24,25 Connecting with other practices that have existing social media policies may also be beneficial. The person in charge of social media policy from another practice can provide key insight on effective policy additions, as well as rules that did not work well. Below are few tips to consider when developing policies:

- Emphasize that the appropriate use of social media is essential for maintaining professional and ethical practice19

- Instruct on privacy, confidentiality, and HIPAA laws, and how they limit disclosures on social media19

- Inform how disparaging remarks against colleagues on social media can adversely affect team-based care19

- Include a reminder that it is impossible to perceive “tone” in online communications25

- Clearly state the expected positive behaviors; examples of possible policy statements about appropriate online behaviors and community expectations might include: “Be respectful, be careful, be responsible, and be accountable”25

Once the social media policy is drafted, inform employees of the new policy. Black22 explains it is important that clinicians know there has been a change to the employee agreement since their initial hire. Employers should consider having an office meeting in which the new policy is reviewed to make sure that everyone understands the guidelines. In addition, all employees should receive a copy of the policy for their personal records.

CONCLUSION

Oral health professionals should not refrain from using social networking sites. Rather, remaining aware of what is posted and becoming more conscious of the risks that can occur when using social media platforms is the key to avoiding the negative pitfalls that can occur with online use. Dental practice owners should consider drafting and implementing social media policies for their employees to prevent unexpected incidences that may result from engagement with the digital world.

REFERENCES

- Farnan JM, Arora VM. Blurring boundaries andonline opportunities. J Clin Ethics. 2011;22:183–186.

- Facebook. Company Info: Key Facts. Availableat: newsroom.fb.com/Key-Facts. Accessed November 12, 2013.

- Statistic Brain. Twitter Statistics. Available at:www.statisticbrain.com/twitter-statistics. Accessed November 12, 2013.

- Instagram. Instagram statistics: Our story.Available at: instagram.com/press/#. Accessed November 12, 2013.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. AHDABylaws & Code of Ethics. Available at: www.adha.org/ resourcesdocs/ 7611_ Bylaws_ and_ Code_ of_Ethics.pdf. Accessed November 12, 2013.

- US Department of Health and Human Services,Office for Civil Rights. Summary of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Available at: www.hhs.gov/ ocr/privacy/hipaa/ understanding/ summary/index.html. Accessed November 12, 2013.

- Black EW, Thompson LA, Duff WP, Dawson K,Saliba H, Black NM. Revisiting social network utilization by physicians-in-training. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2:289–293.

- Thompson LA, Black EW. Nonclinical use of online social networking sites: new and old challenges to medical professionalism. J Clin Ethics. 2011;22:179–182.

- Ragan MR. Social media in the health care provider office. Today’s FDA. 2012;24:20–23.

- Anderson K, Isackson K. Social media policy template for dental offices. Wisconsin Dental Association Journal. 2010;86(4):6.

- Berko RM, Wolvin AD, Wolvin DR, Aitken JE.Communicating: A Social, Career, and CulturalFocus. 12th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson; 2011:480.

- Shore R, Halsey J, Shah K, Crigger BJ, DouglasSP, AMA Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. Report of the AMA Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs: professionalism in the use of social media. J Clin Ethics. 2011;22:165–172.

- Suler J. The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2004;7:321–326.

- Leiker M. When to “friend” a patient: social media tips for health care professionals. WMJ. 2011;110:42–43.

- New York Times. Should Your Doctor Be on Facebook? Available at: http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/04/28/should-your-doctor-be-onfacebook.Accessed November 12, 2013.

- Oakley M, Spallek H. Social media in dental education: a call for research and action. J Dent Educ. 2012;76:279–287.

- Madden M, Fox S, Smith A. Digital Footprints.Available at: www.pewinternet.org/ Reports/ 2007/Digital-Footprints/1-Summary-of-Findings.aspx.Accessed November 12, 2013.

- Bosslet GT, Torke AM, Terry CL, Helft PR. The patient-doctor relationship and online social networks: results of a national survey. J Gen InternMed. 2011;26:1168–1174.

- Spector N, Kappel DM. Guidelines for using electronic and social media: the regulatory perspective. Online J Issues Nurs. 2012;17:1.

- National Ethics Committee of the VeteransHealth Administration. Ethical Boundaries in thePatient-Clinician Relationship. Available at: www.ethics.va.gov/docs/necrpts/NEC_Report_20030 701_Ethical_Boundaries_PtClinician_ Relationship.pdf. Accessed November 12, 2013.

- Kind T, Genrich G, Sodhi A, Chretien KC. Socialmedia policies at US medical schools. Med EducOnline. 2010;15:10.

- Black T. How to write a social media policy.Inc Technology. Available at: www.inc.com/guides/2010/05/writing-a-social-media-policy.html.Accessed November 12, 2013.

- Azark R. Loose lips … it’s time you create asocial media policy for your practice. CDS Rev.2010;103:11.

- Skiba DJ. Nursing education 2.0: The need forsocial media policies for schools of nursing. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2011;32:126–127.

- Junco R. The need for student social mediapolicies. Educause Review Online. Available at: www.educause.edu/ero/article/need-student-socialmedia-policies. Accessed November 12, 2013.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. December 2013;11(12):57–58,61–63.