Addressing the Opioid Epidemic

Oral health professionals can make a difference in decreasing opioid misuse through risk assessment, education, and providing referrals for treatment.

This course was published in the January 2022 issue and expires January 2025. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the opioid crisis.

- Identify the role of dentistry in the opioid crisis during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Develop an overdose prevention strategy for your office.

The COVID-19 pandemic became a public health crisis in March 2020, exacerbating an already present crisis in substance use disorders (SUD).1 Social isolation, financial instability, anxiety, loss of social safety nets, and disruption of addiction treatments contributed to an increase in SUDs and overdoses.1 In the United States, the number of overdoses increased 30% from 2019 to 2020, with synthetic opioids—predominately illicitly manufactured fentanyl (IMF)— causing the most deaths.2 The incidence of opioid use disorder also skyrocketed during the pandemic, as did the rate of untreated mental illness.3

One in four individuals with serious mental illness also has a SUD, which is often related to the overuse of opioids. During the early stages of the pandemic and national stay-at-home orders, the increase in self-reported mental health crises dramatically grew, and suicidal ideation increased by approximately 10%.3 Many individuals with serious mental illness turned to increased substance use to deal with their anxiety, depression, and trauma. As the pandemic wears on, the substance abuse crisis must be addressed with health communication strategies, community-level intervention, and prevention efforts.3

Defining Opioids

Opioids comprise a class of drugs used to manage acute and chronic pain. While these medications are effective at alleviating pain, they also pose a high risk for abuse and addiction. Opioids act by binding to opioid receptors on nerve cells, resulting in the release of dopamine, the “reward” neurotransmitter.4 Dopamine sends messages between nerve cells, and affects motor function, mood, and decision making. Opioid use increases dopamine, resulting in a rush of pleasure. Dopamine also reduces the perception of pain.4 Once the use of opioids becomes consistent, the body slows down its production of dopamine. Over time, a higher dose of the drug is needed to feel the desired effects of dopamine release.1

In 2019, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, reported 10.1 million people ages 12 and older misused prescription opioids.1 IMF is manufactured in illegal labs and often is mixed with heroin, methamphetamine, and/or cocaine.1,5 From 2015 to 2019, the number of overdose deaths involving IMF, heroin, cocaine, and other stimulants rose dramatically even though the number of opioids being prescribed declined.

A schedule II prescription, fentanyl is a synthetic opioid 50 times to 100 times more potent than morphine.6 Fentanyl has a shorter half-life than other opioids and, thus, must be injected more frequently to attain the desired feeling of euphoria; this increases its risk for overdose.

Factors Impacting the Rise in Opioid Use Disorders

The pandemic heightened the impact of social and ethnic inequalities surrounding opioid use disorders. Marginalized populations often face greater stigma regarding abuse and addiction. People of color may refrain from using social services and frequently distrust healthcare and justice systems, leaving a large number of minority patients without treatment for SUDs.1 Additionally, there is a shortage of providers in minority communities as well as a lack of diversity in healthcare professionals. These factors contribute to disparities in the treatment of opioid use disorder. Research demonstrates that for every 35 prescriptions written for medication-assisted treatment to white patients, there is only one for a patient of color.1 This translates into higher risk of overdose deaths in people of color than in whites.1

Before the pandemic, most insurance policies required authorization from prescribing providers for treatment of opioid use disorders. Achieving this authorization became problematic in the midst of shut-down orders. Many patients also faced difficulty accessing clinics that dispensed medication to treat opioid use disorders.7 As a result, policy changes were made to increase access to medication-assisted treatment. For the first time, medication was dispensed in 28-day doses and compliance monitoring was conducted via video conferencing.1

Additionally, testing for the presence of both prescription and illegal drugs decreased rapidly at the start of the pandemic. This impeded access to medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorders.7 Once testing resumed, the positivity rate for nonprescribed fentanyl increased by 35%.6

The lack of access to treatment has long been an issue when trying to address the US’s opioid crisis and the pandemic only exacerbated this. The barriers to care and poor retention in treatment have been deemed the “opioid cascade.”8 Medication-assisted treatment is one of the most successful methods to help individuals recover from opioid use disorder, but there are many impediments to attaining it, including stigma, lack of availability, and unwilling patients. In 2019, approximately 19% of adults with opioid use disorder received medication-assisted treatment.8 Of those who received medication-assisted treatment, only 40% remained compliant 6 months after beginning treatment.8 Many medication-assisted treatment regimens require daily visits to a clinic, which, during the start of the pandemic, became impossible.

Patients accustomed to in-person addiction treatment prior to COVID-19 had to quickly adapt to telehealth. Interruption of treatment, fear of contracting COVID-19, and coping with pandemic-related stress led many individuals to return to drug use.9 Individuals abusing opioids also have a higher risk of contracting COVID-19, as they tend to have less housing security, hindering their ability to socially distance.9 The lack of safe needle exchanges due to the pandemic also raises the risk of COVID-19.9 Active users often have additional comorbidities due to their opioid use, which may increase the likelihood of hospitalization and need for mechanical ventilation.

Role of Oral Health Professionals in Addressing Opioid Use Disorders

The dental team’s most effective preventive measure is education. Continuing education is key to identifying patients with a history of opioid use disorders, those currently misusing opioids, and the signs and symptoms associated with addiction. Education can also help the team stay current with state and federal regulations related to opioids.

Oral health professionals can play an important role in identifying and referring patients in need of treatment for opioid use disorders. During the pandemic, it became apparent that all healthcare professionals are crucial in recognizing the signs of social isolation and anxiety, as well identifying those without safety nets. Dental hygienists may be the first to recognize those struggling with opioid use disorders due to the amount of time spent building rapport with patients.10,11 In order to feel comfortable discussing opioid misuse, dental hygienists should complete a course on addiction. By expanding their knowledge, dental hygienists will be better equipped to identify signs of substance abuse and more confident in talking to patients about misuse.10

The first step in identifying patients at risk for opioid use disorder is to include questions regarding substance use and/or abuse on the medical history. There is stigma attached to substance abuse, so approaching the topic without judgment is paramount. Patients should know that all answers are confidential, and that opioid use can potentially affect treatment and outcomes. The negative effects of opioids should also be discussed with patients.10

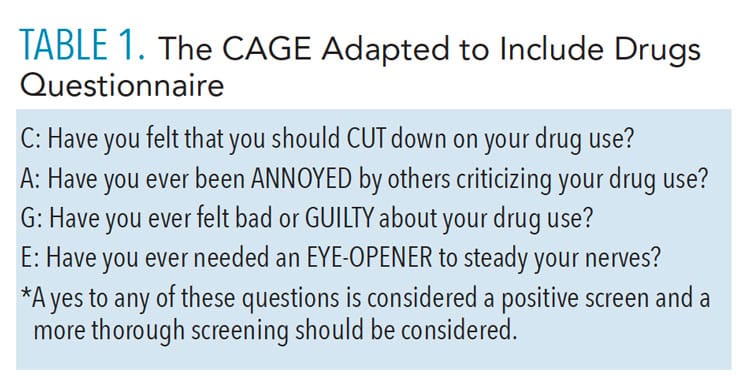

The screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment model is an evidence-based practice to help identify, reduce, and prevent problematic use of alcohol and illicit drugs.10 A quick screening such as this can help identify those at risk for opioid use disorder.11 The CAGE-Adapted to Include Drugs questionnaire is another convenient screening option (Table 1, page 29). If the patient responds yes to any of the four questions, a brief discussion on the use of opioids should occur (brief intervention). All clinicians should have a list of local resources for patients who may need a referral for treatment.12

Oral health professionals have a responsibility to help combat opioid use disorders through making informed prescription choices. The American Dental Association recommends nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as a primary control for pain caused by dental procedures.13 While the prescription of opioids has decreased across all healthcare professions, those made by dental providers have not decreased as dramatically.13 A recent national survey demonstrated that while dentists believe NSAIDs and acetaminophen combinations are equally as effective as prescription opioids, 43% of respondents reported regularly prescribing opioids for pain management; 69% reported seeing patients who abuse opioids. Of those who prescribe opioids, 50% prescribe an amount that will result in leftover medication.13 Opioid misuse and abuse in dental patients may lead to adverse events, including overdoses. When prescribing opioids, patients should be instructed on how to dispose of extra medication.

When extensive treatment is indicated, a discussion must be initiated with patients about pain management. Oral health professionals need to assure patients that NSAIDs and acetaminophen combinations can effectively provide relief. Patients with a history of addiction should be reassured that their pain can be managed conservatively. For mild pain relief, ibuprofen should be considered. For moderate-to-severe pain relief, a combination of ibuprofen and acetaminophen is the pain management of choice. Opioids are only advised for severe pain, and should be limited to a 3-day supply or less.7

Before writing a prescription for opioids, the state’s prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) should be reviewed to help determine how many opioid prescriptions the patient has received in the past.10 In a 2019 national survey, 47% of responding dentists said they had never accessed their state’s PDMP.13 Lack of awareness, not understanding how to register, and confusion about how to use the PDMP were reasons why dentists had not utilized this valuable tool. While participants felt the program was very helpful, a majority found it did not change their prescribing behaviors. States with mandated PDMP utilization had a higher rate of dentists engaging in the program. It is important to identify each state’s requirements as there is no general consistency or guidance.13 Federal requirements would help with consistency and utilization.14

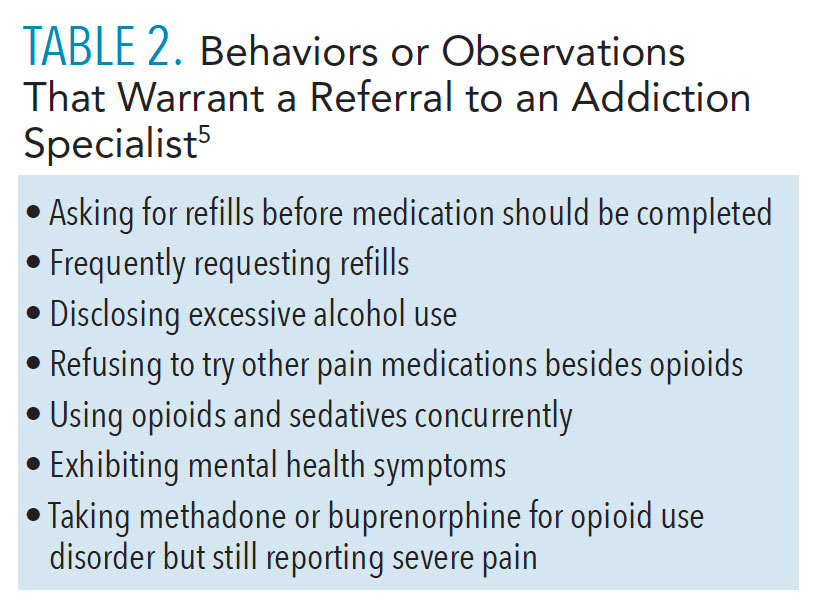

Oral health professionals should be knowledgeable on when to refer a patient to an addiction specialist. Table 2 lists behaviors or observations that would warrant a referral to an addiction specialist.5 If possible, the office should have a network of addiction specialists for timely referral. Unfortunately, this may be difficult in more rural areas. More providers who specialize in treating opioid use disorders are severely needed.7

![TABLE 2. Behaviors or Observations That Warrant a Referral to an Addiction Specialist5]() Overdose Prevention Strategy

Overdose Prevention Strategy

The US Department of Health and Human Services released a guide on overdose prevention strategy in response to the 250% increase in overdose deaths from 1999 to 2019.15 The guide asserts that primary prevention—including prevention programs and safe prescribing practices—is the first step. To recognize and prevent overdoses, interprofessional healthcare teams are necessary.15

The second step is to access to evidence-based treatment. While oral health professionals do not treat opioid use disorder, they can provide referrals for treatment. The dental team can also use motivational interviewing to help patients identify ways to overcome social barriers to treatment. New treatments are also needed to help engage patients in their own care and improve compliance.8 Continuing education for oral health professionals should include communication strategies on how to discuss opioid use disorder and referral for treatment.10,11 The dental team should have referral sources for pain management doctors, addiction specialists, and counselors.7

Medication-assisted treatment using either methadone or buprenorphine is the most common approach to opioid use disorder.7 While methadone has been the treatment of choice historically, buprenorphine is becoming more frequently prescribed.7 Methadone is only administered in outpatient clinics, which posed significant challenges during the shut-down phase of the pandemic. Patients on a buprenorphine regimen receive a 28-day prescription and do not require monitoring. This is because buprenorphine is an opioid partial agonist that blocks opioid receptors if a patient concurrently uses an opioid.7 Patients on both methadone and buprenorphine regimens will experience withdrawal symptoms if the medications are ceased. When treating patients on buprenorphine, ensuring adequate anesthesia to reduce post-operative pain as long as possible is important to reduce the need for opioids to manage pain.7 Oral health professionals should consult with a patient’s addiction specialist before prescribing pain medication.

The third step in overdose prevention strategy is harm reduction.15 While every state recorded increased overdoses during the pandemic, prescriptions of buprenorphine and naloxone only increased slightly during the past 3 years.15 Naloxone is a common harm-reduction medication, as it is an opioid antagonist that binds opioid receptors in the brain, effectively blocking opioid receptors and reversing respiratory depression.16 When a patient receives a prescription for high-dose opioids or opioid plus benzodiazepines, they should receive a prescription for naloxone.17 Naloxone is critical part of treating opioid use disorder, yet only one prescription for every 70 high-dose opioid prescriptions is dispensed.16 One of the barriers to its use is the copay required for patients covered by Medicaid. This creates a healthcare inequity among low-income patients.11 If a patient is at high risk for opioid use disorder, the dental team should consider a naloxone prescription if opioids are prescribed.

The risk for opioid overdose is high for patients who receive a dosage of 50 morphine milligram equivalents per day or greater; have chronic respiratory conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or sleep apnea; have been prescribed benzodiazepines or have a nonopioid substance use disorder, such as alcohol abuse; or are diagnosed with a mental health disorder.15 A thorough medical history is necessary and a discussion on the use of opioids in the past is necessary before a prescription is written.14 If the risk for opioid use disorder is high, the dental professional should consider NSAID and acetaminophen combination instead of an opioid prescription.

The final step in the prevention of opioid misuse is recovery support.15 Patients utilizing recovery support services experience better long-term outcomes. An interprofessional recovery support team can help patients refrain from opioid use.15 The interprofessional team should consist of an addiction specialist, psychologist, and treatment center representative. The dental team can be part of this journey through encouragement in recovery and helping patients achieve optimal oral health.

As part of recovery support in the dental office, the Self-Management and Recovery Training Recovery Program can be implemented.7 This five-step motivational interviewing process solicits behavioral changes in the patient with opioid use disorder. The first step is to work with the patient to understand the reality of the problem and how it affects his or her health. The second step is to listen with empathy to the patient’s perspective, which can help remove resistance to change. Address ambivalence using motivational interviewing to explore why the patient wants to continue to use and why he or she should quit. If the patient is resistant to change, the clinician should modify the approach because arguing creates greater resistance. Finally, support self-efficacy through encouraging the patient to explore his or her situation and help identify possible changes.7

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has negatively impacted efforts to reduce the prevalence of opioid use disorder and overdoses. Oral health professionals can be part of a prevention effort to reduce the misuse opioids. More education on risk assessment for opioid use disorder and how to communicate with a patient needing treatment is needed. Oral health professionals must plan for pain management without putting patients at risk.

References

- American Medical Association. National Roadmap on State-Level Efforts to End the Nation’s Drug Overdose Epidemic: Leading-Edge Practices and Next Steps to Remove Barriers to Evidence-Based Patient Care. Available at: ama-assn.org/system/files/2020-12/ama-manatt-health-2020-national-roadmap.pdf. Accessed December 13, 2021.

- Ahmad FB, Rossen LM, Sutton P. Provisional drug overdose death counts. Available at: cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm. Accessed December 13, 2021.

- Czeisler M, Lane R, Petrosky E, et ak. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic-United States, June 24-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69: 1049–1047.

- Mayo Clinic. How Opioid Addiction Occurs. Available at: mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/prescription-drug-abuse/in-depth/how-opioid-addiction-occurs/art-20360372. Accessed December 13, 2021.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Available at store.samhsa.gov/product/key-substance-use-and-mental-health-indicators-in-the-united-states-results-from-the-2019-national-survey-on-Drug-Use-and-Health/PEP20-07-01-001. Accessed December 13, 2021.

- Niles J, Gudin J, Radcliff J, Kaufman H. The opioid Epidemic Within the COVID-19 Pandemic: Drug Testing in 2020. Population Health Management. 2021;24:S1.

- Nack B, Haas S Portnof J. Opioid use disorder in dental patients: the latest on how to identify, treat, refer and apply laws and regulations in your practice. Anesth Prog. 2017;64:178-187.

- Nunes E, Levin F, Reilly M, El-Bassel N. Medication treatment for opioid use disorder int the age of COVID-19: Can new regulations modify the opioid cascade? J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;122:108196.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 and People at Increased Risk. Available at: cdc.gov/drugoverdose/resources/covid-drugs-QA.html. Accessed December 13, 2021.

- National Institutes of Health. Screening for Substance Use in the Dental Setting. Available at: drugabuse.gov/nidamed-medical-health-professionals/science-to-medicine/screening-substance-use/in-dental-setting#. Accessed December 13, 2021.

- Hoang E, Keith, D, Kullch, R. Controlled substance misuse risk assessment and prescription monitoring database use by dentists. J Am Dent Assoc. 2019;150:383–392.

- Melton ST, Orr RT. Detection and deterrence of substance use disorders and drug diversion in dental practice. The ADA Practical Guide of Substance Use Disorders and Safe Prescribing. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley Blackwell; 2015.

- Heron M, Nwokorie N, O’Connor B, Brown R, Fugh-Berman A. Survey of opioid prescribing among dentists indicates need for more effective education regarding pain management. J Am Dent Assoc. October 21, 2021.

- McCauley JL, Gilbert GH, Cochran DL, et al. Prescription drug monitoring program use: national dental pbrn results. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2019;4:178–186.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Overdose prevention strategy. Available at: hhs.gov/overdose-prevention. Accessed December 13, 2021.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Naloxone. Available at: drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/naloxone. Accessed December 13, 2021.

- American Medical Association. 2021 Overdose Epidemic Report: Physicians’ Actions to Help End the Nation’s Drug-Related Overdose and Death Epidemic and What Still Needs to Be Done. Available at: end-overdose-epidemic.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/AMA-2021-Overdose-Epidemic-Report_92021.pdf. Accessed December 13, 2021.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2022;20(1):28,31-33.