A Primer on Common Oral Conditions

The causes, development, and treatment for the most frequently encountered pathologies of the oral cavity.

This course was published in the April 2009 issue and expires April 2021. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Describe the clinical appearance and therapeutic management of aphthous ulcers and identify the circumstances when referral is mandatory.

- Describe how to identify aphthous ulcers versus intraoral herpetic lesions.

- Recognize and manage oral herpetic lesions.

Dental hygienists play a key role in supporting the health and well-being of their patients. The need for oral health care practitioners who have a broad education, with the ability to make an early diagnosis of oral diseases or refer, is of outmost importance.

The dental hygienist has the opportunity to impact a patient’s overall health by performing a thorough extra-oral and intra-oral soft tissue evaluation to detect signs of various pathologies.

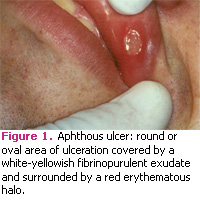

ULCERATIONS OF THE MUCOSA

Ulcerative lesions of the oral cavity are among the most common mucosal alterations. They affect approximately 20% of the population,1 with the incidence rising to more than 50% in certain groups.2 Children from high socioeconomic groups may be affected more than those from low socioeconomic groups.3 Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS), commonly referred to as canker sores, is among the most frequent diagnosis made worldwide.4 Clinically, aphthous ulcers are round or oval shaped areas of ulcerations that are covered by a whiteyellowish fibrinopurulent exudate and are surrounded by an erythematous border or halo (Figure 1).5 These lesions are extremely painful and the level of discomfort is often disproportionate to the clinical appearance. The distribution of these lesions is very important for diagnostic purposes. They affect the areas of the mucosa that are nonkeratinized and not bound to bone. Typical locations include the ventral surface of the tongue, floor of the mouth, buccal mucosa, labial mucosa, and soft palate.6 Aphthous ulcers are self-limiting and are characterized by spontaneous healing and recurrences. The cause is unknown but they have been linked to an immune deregulation of T-cells.7 Evidence of genetic predisposition exists, since 40% to 50% of those with RAS have a family history of the condition.8 According to the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, aphthous ulcers may be associated with a dysfunctional immune system that uses the body’s defenses to attack the normal cells of the oral mucosa. In addition, 30% of people who suffer from recurrent aphthous ulcers have a history of allergies.9 Three basic clinical variants of aphthous ulcers exist and are classified depending on the size of the lesions.2

Minor aphthous stomatitis is the most common variant. These lesions are typically small and do not exceed 1 cm in diameter.5 Healing takes place within 1 week to 2 weeks without evidence of scarring. Minor aphthous stomatitis has the fewest number of lesions and recurrences per year.

Major aphthous stomatitis is a less common but a more severe condition that affects approximately 10% to 15% of all patients with aphthous ulcers. These lesions can be extremely painful and are characterized by large ulcerations that measure greater than 1 cm in diameter. The number of ulcers can vary from one to five and they often have irregular borders with a depressed base.6 The lesions have a prolonged healing time of 2 weeks or more and are associated with scarring.

Herpetiform aphthous stomatitis is the least common, occurring in less than 5% of people with RAS. The lesions form in small clusters or crops, hence the designation herpetiform. They consist of pinpoint ulcerations that can measure less than 1 mm to 3 mm in diameter. The number of lesions vary but can range from crops of 10 to 100.5 The individual lesions often coalesce and can form larger areas of ulcerations. Healing takes approximately 1 week, however this variant is associated with the shortest ulcer-free period. Recurrences are frequent and new clusters often appear as older lesions are in the process of resolution.

A large number of therapeutic agents are available for the treatment of RAS. The main goal of therapy is to decrease pain, expedite healing, and prevent recurrences. Most cases of RAS are mild and represent self-limiting processes that do not require therapeutic management other than palliative measures to ensure patient comfort. Severe cases are accompanied by intense pain and alter the patient’s ability to eat and speak.

Several over-the-counter formulations are available to treat uncomplicated cases of RAS, including occlusive agents, topical anesthetics, and antiseptics. Topical anesthetics, like benzocaine or dyclonine, provide symptomatic relief. Some preparations combine topical anesthetics with mucoadhesive agents for better mucosal adherence; various formulations and strengths are commercially available. A mixture of equal parts of viscous lidocaine, Maalox, and children’s Benadryl provides palliative relief and coats the lesions to ensure patient comfort before meals. Occlusive agents provide a protective barrier against further tissue trauma and, therefore, promote healing. Certain occlusive agents are compounded with topical anesthetics, however, some formulations have a high content of alcohol and produce an initial sting at the time of application.

The most common topical antiseptic preparations contain hydrogen peroxide or sodium bicarbonate and reduce the number of microorganisms on the surface of the ulcer. Tetracycline rinses may decrease lesion size, duration, and pain while antimicrobial rinses, like chlorhexidine, have proven beneficial only on occasion.10 For the treatment of more severe cases of RAS, prescription topical and systemic steroid formulations are available and are the mainstay of treatment. Topical steroids are effective in expediting the resolution of the lesions but do not reduce the frequency of recurrences.11 Systemic prednisone is reserved for the most severe cases and those who do not respond well to topical measures. A short burst of systemic prednisone is typically recommended to avoid the long-term side effects of the medication.11 As a general rule, an ulcer that has not healed for more than 2 weeks should be biopsied to rule out other pathologic processes. In addition, when a complex aphthosis is present, a number of systemic conditions, nutritional deficiencies, and syndromes should be considered and the patient should be referred to an oral pathologist for further evaluation.

|

|

HERPES VIRUS INFECTIONS

Herpetic lesions are common viral infections of the orofacial region that affect both adults and children.12 There are eight herpes viruses that are pathogenic to humans and are also known as the human herpes viruses (HHV). HHV-1 and HHV-2, also designated as herpes simplex virus (HSV) 1 and 2 respectively, are responsible for all orofacial herpetic viral infections. Most of the cases of orofacial herpes involve herpes simplex virus 1 while herpes simplex 2 is typically associated with cases of genital herpes.13 Recent studies show that a significant number of cases of orofacial herpes are associated with herpes simplex virus 2.13,14

The incidence of orofacial cases that involve herpes simplex virus 2 is on the rise and is related to sexual practices that include orogenital contact.13 Both herpes viruses can infect the orofacial region and produce similar clinical features. Therefore, it is not possible to distinguish the type of herpes virus that is responsible for a given lesion through clinical evaluation. The virus can produce two forms of disease: a primary infection that represents the patient’s initial exposure to the virus and a secondary or recurrent form.

The incidence of orofacial cases that involve herpes simplex virus 2 is on the rise and is related to sexual practices that include orogenital contact.13 Both herpes viruses can infect the orofacial region and produce similar clinical features. Therefore, it is not possible to distinguish the type of herpes virus that is responsible for a given lesion through clinical evaluation. The virus can produce two forms of disease: a primary infection that represents the patient’s initial exposure to the virus and a secondary or recurrent form.

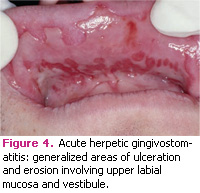

PRIMARY HERPES INFECTION

Out of initial herpes simplex virus infections, 99% are asymptomatic. Only 1% of those infected experience an acute symptomatic infection designated as acute herpetic gingivostomatitis (AHG). This disease is more common in childhood or puberty but a small percentage occur in adults who have not previously been exposed to the virus. Acute herpetic gingivostomatitis is characterized by generalized areas of ulceration in the oral mucosa, affecting both keratinized and nonkeratinized tissue. (Figures 2-4) The skin around the mouth and lips may also be involved. The lesions are always preceded by yellow fluid-filled vesicles. Intra-orally these vesicles rupture almost immediately, leaving painful areas of erosions or ulcerations. Gingival inflammation and swelling are common sequellae to the disease process. Patients usually exhibit systemic symptoms like fever, malaise, and anterior cervical lymphadenopathy. In immunocompetent patients, acute herpetic gingivostomatitis is a self-limiting process and usually resolves in 7-14 days. The treatment should include palliative measures to ensure patient comfort; topical anesthetics and coating agents are typically effective. Proper hydration is important, especially for children, during the disease outbreak. Systemic antiviral therapy is effective only if started within the first 2 days after the onset of symptoms. Some examples of systemic antiviral therapies include acyclovir or valacyclovir. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines recommend systemic acyclovir for oral herpes infections in immunocompromised patients.15

After the initial infection, the virus has the ability to reside in an inactive form within the host forever.16 HSV has the ability to bypass the host’s immune system by traveling along the trigeminal nerve and residing within the trigeminal ganglion, where it remains dormant until reactivation.17 Once reactivated, the virus travels via the trigeminal nerve and allows for the development of a recurrent lesion, commonly known as a cold sore or fever blister, at the site of initial infection.

The mechanism of viral reactivation is poorly understood but periods of immunosupression, stress, sunlight, or tissue trauma are thought to be the most common causes of recurrences. Asymptomatic reactivation of the virus occurs in approximately 9% of patients.18 During these periods, the patient releases viral particles into the saliva without a visible recurrent lesion forming.19 Patients are infectious during these periods and most transmissions occur during periods of asymptomatic viral shedding.13

SECONDARY HSV INFECTION

RECURRENT HERPES LABIALIS

Recurrent herpes labialis, colloquially called cold sores or fever blisters, are common. Recurrent herpes labialis include painful areas of ulcerations that are preceded by vesicles that occur in the area of the commissure of the mouth and around the lips. Early lesions consist of fluid-filled vesicles that rupture and subsequently form a hard, irregular crust. Patients should be warned not to touch active lesions due to risk of autoinoculation to other areas.

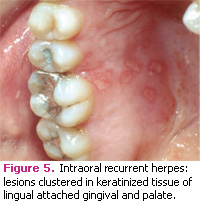

INTRA-ORAL RECURRENT HERPES

Intra-oral recurrent herpes is the term used when the virus produces lesions on bonebearing tissues (attached gingiva and palatal mucosa). Cases of intra-oral herpes are commonly seen after tissue trauma that occurs with dental treatment. Recurrent herpes is a self-limiting process that typically resolves in about 7 days to 14 days. However, the condition can be dangerous in patients who have a compromised immune system (HIV/AIDS, leukemia, or organ transplant recipients). Without proper immune function, recurrent herpes can persist and spread. The infection may be treated with antiviral drugs. Failure to do so may result in the patient’s death.

TREATMENT

The treatment of recurrent herpes includes the use of topical antiviral medications. Peniclovir (Denavir®), an antiviral prescription cream or Docosanol (Abreva®), an over-the-counter cream, may be used during the initial onset of symptoms with modest results.21,22 Systemic antiviral medications are also available but typically reserved for those who have more frequent or severe recurrences. Valacyclovir (Valtrex®) is FDAapproved for the prevention and management of recurrent herpes. This medication should be started during the prodrome stage and as early as possible to maximize effectiveness.23

In order to prevent cross-contamination, patients with active herpetic lesions should be rescheduled because the virus could be spread. One of the most severe examples would be the spread of the herpes virus to the ocular area. If this happens, the patient could be at risk for blindness. When herpetic lesions start to develop a crust on the surface, they are still infectious but the risk for spreading is low compared to an active vesicle.

INTRAORAL HERPES OR APHTHOUS ULCERS?

Intraoral herpes may be confused with aphthous ulcerations. Both conditions have small, painful lesions that usually resolve in 7 days to 14 days.6 There are notable differences between the two entities. Intraoral herpes affects bone-bearing tissues or keratinized mucosa (palate, attached gingival, or dorsal surface of the tongue) while aphthous ulcers occur in soft, movable tissues that are nonkeratinized (labial and buccal mucosa, ventral surface of the tongue, and floor of the mouth).6

Herpetic lesions are preceded by vesicles that rupture and leave an area of ulceration or erosion. Vesicles do not precede aphthous ulcers.6 Herpetic lesions have a tendency to occur in the same place and heal in a predictable fashion for the patient. Aphthous ulcers occur in different areas of the mouth.

REFERENCES

- Axell T, Henricsson V. Association between recurrent aphthous ulcers and tobacco habits. Scand J Dent Res. 1985;93:239-242.

- Field EA, Allan RB. Review article: oral ulceration—aetiopathogenesis, clinical diagnosis and manage ment in the gastrointestinal clinic. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:949-962.

- Crivelli M, Aguas S, Adler I, Quarracino C, Bazerque P. Influence of socioeconomic status on oral mucosa lesion prevalence in schoolchildren. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1988;16:58-60.

- Axell T, Henricsson V. The occurrence of recurrent aphthous ulcers in an adult Swedish population. Acta Odontol Scand. 1985;43:121-125.

- Lehner T. Pathology of recurrent oral ulceration and oral ulceration in Behcet’s syndrome: light, electron and fluorescence microscopy. J Pathol. 1969;97:481-494.

- Weathers DR, Griffin JW. Intraoral ulcerations of recurrent herpes simplex and recurrent aphthae: two distinct clinical entities. J Am Dent Assoc. 1970;81: 81-87.

- Savage NW, Seymour GJ. Specific lymphocytotoxic destruction of autologous epithelial cell targets in recur rent aphthous stomatitis. Aust Dent J. 1994; 39:98-104.

- Aphthous stomatitis is linked to mechanical injuries, iron and vitamin deficiencies, and certain HLA types. JAMA. 1982;247:774-775.

- Wray D, Vlagopoulos T, Siraganian R. Food allergens and basophil histamine release in recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1982;54:388-395.

- Hunter L, Addy M. Chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash in the management of minor aphthous ulceration. A double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial. Br Dent J. 1987;162:106-110.

- Vincent SD, Lilly GE. Clinical, historic, and therapeutic features of aphthous stomatitis. Literature review and open clinical trial employing steroids. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;74: 79-86.

- Eisen D. The clinical characteristics of intraoral herpes simplex virus infection in 52 immuno compe – tent patients. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology. 1998;86: 432-437.

- Embil JA, Manuel FR, McFarlane ES. Concurrent oral and genital infection with an identical strain of herpes simplex virus type 1. Restriction endonuclease analysis. Sex Transm Dis. 1981;8:70-72.

- Langenberg AG, Corey L, Ashley RL, Leong WP, Straus SE. A prospective study of new infections with herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2. Chiron HSV Vaccine Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1432-1438.

- Arduino PG, Porter SR. Oral and perioral herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection: review of its management. Oral Dis. 2006;12:254-270.

- Baringer JR. Herpes simplex virus in human sensory ganglia. IARC Sci Publ. 1975;1:73-77.

- Baringer JR, Swoveland P. Recovery of herpessimplex virus from human trigeminal ganglions. N Engl J Med. 1973;288:648-650.

- Wheeler CE Jr. The herpes simplex problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:163-168.

- Knaup B, Schunemann S, Wolff MH. Subclinical reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 in the oral cavity. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2000;15:281- 283.

- Sanderson RJ, Ironside JA. Squamous cell carci – nomas of the head and neck. BMJ. 2002;325:822-827.

- Raborn GW, Martel AY, Lassonde M, Lewis MA, Boon R, Spruance SL. Effective treatment of herpes simplex labialis with penciclovir cream: combined results of two trials. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133: 303-309.

- Schmid-Wendtner MH, Korting HC. Penciclovir cream—improved topical treatment for herpes simplex infections. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2004;17:214-218.

- Woo SB, Challacombe SJ. Management of recurrent oral herpes simplex infections. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103(Suppl):12-18.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2009; 7(4): 38-41.