The Importance of Maternal-Infant Oral Health

As the link between maternal and infant oral health becomes more clear, dental hygiene practice must also evolve to reflect this new knowledge.

This course was published in the December 2019 issue and expires December 2022. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Explain the relationship of maternal-infant health within the context of oral microbiomes.

- Discuss the importance of maternal-infant oral health before, during, and after pregnancy.

- Identify how the dental hygienist can support maternal-infant oral health in clinical practice.

The quality of a mother’s prenatal oral health has been shown to not only affect fetal growth and development, but also her child’s health through infancy, childhood, adolescence, and adulthood.1,2 This mother-infant relationship is complex and dynamic, involving not only genetics and biology but also environmental and social factors. Studies demonstrate that health is determined by the interaction between microbial species within the human body. Microbiomes between a mother and infant are showing associative long-term impacts on the infant’s growth and developing health later in life. As this link between maternal and infant oral health evolves, dental hygiene knowledge and practice must also progress to reflect these new developments.

MICROBIOME-BASED UNDERSTANDING

Determinants of health are derived from complex and multidimensional genetic, biological, environmental, and social factors.3 The hereditary and environmental aspects play important and intimately intertwined roles in the development of health.4 Pregnancy and infant growth and development exemplify this process of nature and nurture. In this nature and nurture model, traits are inherited through vertical transmission between mother and infant, whereas horizontal transmission occurs through an individual’s environment and learned behaviors.5,6

Just as systemic diseases, such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus, have been linked to adverse birth outcomes, oral diseases can impact pregnancy and fetal health.7,8 Gingivitis and periodontitis, for example, are prevalent forms of disease that have been linked to preterm birth and low birth weight.8,9 These conditions incite extensive inflammatory reactions through mediators, such as lipopolysaccharides and cytokines (Figure 1), that can extend beyond the local periodontium and into the placenta.9 The risk of developing pre-eclampsia, a complication specific to pregnancy that can significantly compromise the health of a mother and fetus, has been shown to increase in mothers with periodontal diseases.10 Although the average gestation period is approximately 40 weeks, the influence of maternal oral health continues after birth because oral health practices and perceptions are environmentally transferred from mother to child.2,3,6,11

The nature and nurture model of growth and development is also becoming better understood within the context of the human microbiome and health. The human microbiome describes the collection of genomes derived from communities of microbial species—such as bacteria, fungi, and archaea—in various parts of the body that share in complex and dynamic interactions.12,13 Each individual possesses approximately 20,000 genes, but the microbes that inhabit the body outnumber human cells by at least 10-fold.12 The ever-changing interactions between the body and microbes on and within the body determine states of well-being.

The oral cavity consists of its own unique microbiome that reflects these dynamic interactions of microbes that establish health and disease in the individual.14–21 In the oral microbiome, this balancing act is most evident in oral diseases such as gingivitis and dental caries.21 When the microbiological diversity is in symbiotic balance, a state of health is established.20,21 No host immune responses are elicited, nor do alterations of the normal cellular or tissue functions occur. When microbiological diversity is in a dysbiotic state, however, unbalanced interactions between microorganisms result in host immune responses with alterations of normal cellular and tissue functions.20

Pregnancy and birth present the processes that form and establish microbial communities in a new individual.22–24 Prior to birth, the infant’s microbiomes are not typically colonized; however, as early as the first 24 hours after birth, the infant’s microbiomes show shared species with the mother, which continue to be influenced up to 4 months post-partum.25 The infant’s microbiomes can acquire microorganisms through various means (eg, direct transfer of bacteria from the mother and contact with the microbes within the external environment).24 Within the oral cavity, a significant proportion of an infant’s oral microbiome is derived from its maternal counterpart.22,24,25

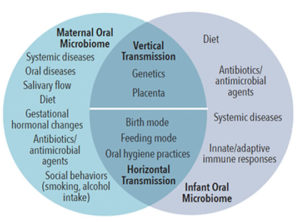

The maternal microbiome has been shown to predicate the types of microbes tolerated by the infant, thereby, the infant’s microbiome is reflective of his or her mother’s (Figure 2).24 A study investigating mother-to-infant microbial transmission found that while all mothers carried Fusobacterium nucleatum and Campylobacter rectus—two common periodontal pathogens—only the oral microbiomes of children with mothers who were smokers demonstrated the ability for colonization of these microbes.22 Additionally, the infant’s exposure to the placental environment of the mother during gestation has been shown to influence the oral microbiome that is acquired, as it shares microorganisms that are found in the mother’s microbiome.23,24,26

After gestation, the maternal influence on the infant’s emerging oral microbiomes persists. Different types of birth modes influence the infant’s oral microbiomes. One study found that Streptococcus mutans were present in infants born via caesarian section approximately 1 year before their vaginally born counterparts.27 The type of feeding that an infant engages can also impact the type of microbes present in the oral cavity. In a study that looked at the oral microbiota of 3-month-old breast-fed infants and formula-fed infants, only those who were breast fed had a species of Lactobacillus that inhibited the colonization of oral Streptococcus.28

Through understanding the development of the infant’s oral microbiome and its interrelated nature with the mother’s microbiomes, individuals at higher risk for disease can be identified early and more effective preventive and interventional treatments can be developed.24 This capability arises from the knowledge that the interactions between microorganisms and the host (ie, mother or infant) determine the state of health and disease because this interplay is what influences the innate and adaptive immune responses of the host.15,16,21,24,29 When the composition and proportions of microbial species within the mother’s oral microbiome favor a dysbiotic state, and those microorganisms are more readily colonized in the infant, then the infant’s oral microbiome may be at greater risk for developing disease. Besides genetics, the environmental effect on the oral microbiome, through behaviors like sugar intake and oral hygiene, have been associated with disease-producing effects from the microbiome’s microorganisms’ interactions and functions.28 Given that the infant’s behavioral development has close maternal ties, his or her oral microbiome can be exposed to similar environmental factors.

As maternal and infant oral health are linked before, during, and after pregnancy at the microbiological level, providers within the fields of primary care, obstetrics, pediatrics, and oral health share a mutual responsibility in caring for the past, present, and future needs of both mother and infant.7,30,31 Improvement of a mother’s oral health before and after pregnancy can lead to meaningful and compounding positive improvements in the ultimate growth and development of an infant as he or she progresses into adulthood.6,32,33 Additionally, poor oral health patterns can persist generationally.2,34

DENTAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR MOTHER AND INFANT

Dental hygienists play a vital role in promoting oral health during conception, pregnancy, and post-partum. Oral health care is safe during the perinatal period and is essential for the health of the developing fetus and mother.35,36 Just as hormonal and physiological changes occur to the body during pregnancy, the oral cavity is impacted as well.37 Pregnancy, in particular, frequently increases the risk of oral health complications. Delaying dental treatment can pose indirect and unnecessary acute risks on the fetus in the event of odontogenic or periodontal infections. After birth, the infant’s long-term oral health also relies on continued oral health care. Dental hygiene therapy, appropriate prevention, and disease management can benefit both mother and infant.

Dental hygienists can identify and treat several commonly encountered oral complications that arise during pregnancy. A comprehensive gingival and periodontal oral assessment should be performed to identify any changes to the gingival tissues, as pregnancy gingivitis is one of the most common oral complications during pregnancy, affecting 60% to 75% of all pregnant women.38 It is identified as red, enlarged gingival tissue that bleeds easily and shares the same clinical signs of plaque induced gingivitis. As opposed to being plaque-induced, it is caused from elevated progesterone and estrogen levels in the body.

Granuloma gravidarium, also known as pyogenic granuloma or pregnancy tumor, is another possible pregnancy complication. Although rare, it does present in 0.2% to 9.6% of pregnant women.38,39 Identified as a proliferative red to purple nodular mass extending from the gingival tissue, it typically presents as a single mass that bleeds easily and is most commonly found on the maxillary, anterior interdental papilla.38,39 This type of granuloma usually appears in the second trimester of pregnancy and continues to increase in size until delivery. Although both of these common gingival side effects resolve after birth, dental hygiene intervention through scaling and root planing or dental prophylaxis and oral hygiene instruction may improve these conditions.40

Another possible oral complication during pregnancy is the development of dental caries or changes to the tooth enamel or dentin. These changes may be observed during pregnancy due to the effects of vomiting caused by morning sickness and/or cravings of higher acidic foods and beverages such as sweet treats, citrus fruits, juices, or carbonated beverages.37,38 Dental hygienists can identify vomiting-induced erosion on the lingual surface of the maxillary molars and incisors, whereas changes due to an acidic pH level in the oral cavity have a more generalized effect on all of the dentition. If the mother experiences morning sickness, dental hygienists can instruct the mother to rinse with water following vomiting incidences and avoid brushing for at least an hour to allow the oral cavity pH level to neutralize.

After birth, dental hygienists can continue to care for the mother as well as facilitate care for the infant.11 Anticipatory guidance related to the infant’s oral health can be provided by the dental team, especially the dental hygienist, during the perinatal phase.11 This type of counseling includes instruction on when to establish infant oral health care and how to care for the primary and permanent phases of the dentition. The dental hygienist can also participate in risk assessment in relation to dental and periodontal diseases of the infant based on the status of the mother’s oral health.

CONCLUSION

Maternal and infant oral health are intricately linked beyond pregnancy. The establishment and development of oral health occurs at the microbiological level and is now understood to be a dynamic relationship not only between microbes of the oral environment, but also between the microbiomes of the mother and infant. As such, oral health professionals and their clinical practices need to reflect the connected nature between mother and infant. The dental hygienist is a key component to caring for the past, present, and future needs of the mother and infant.

REFERENCES

- Ekman B, Pathmanathan I, Liljestrand J. Integrating health interventions for women, newborn babies, and children: a framework for action. The Lancet. 2008;372:990–1000.

- Boggess KA, Edelstein BL. Oral health in women during preconception and pregnancy: implications for birth outcomes and infant oral health. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10(5 Suppl):S169–174.

- Fisher-Owens SA, Gansky SA, Platt LJ, et al. Influences on children’s oral health: a conceptual model. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e510–520.

- Shonkoff JP, Phillips DA, eds. Rethinking nature and nurture. In: From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development. Available at: nap.edu/read/9824/chapter/1. Accessed November 18, 2019.

- Khoury MJ. Genetics and genomics in practice: the continuum from genetic disease to genetic information in health and disease. Genet Med. 2003;5:261–268.

- Shearer DM, Thomson WM, Broadbent JM, Poulton R. Maternal oral health predicts their children’s caries experience in adulthood. J Dent Res. 2011;90:672–677.

- Hartnett E, Haber J, Krainovich-Miller B, et al. Oral Health in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2016;45:565–573.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion. Available at: acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/Oral-Health-Care-During-Pregnancy-and-Through-the-Lifespan?IsMobileSet=false. Accessed November 23, 2019.

- Wu M, Chen SW, Jiang SY. Relationship between gingival inflammation and pregnancy. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:623427.

- Ha JE, Jun JK, Ko HJ, Paik DI, Bae KH. Association between periodontitis and preeclampsia in never-smokers: a prospective study. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41:869–874.

- Perinatal and infant oral health care. Pediatr Dent. 2017;39:208–212.

- Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Hamady M, et al. The human microbiome project. Nature. 2007;449:804–810.

- Ursell LK, Metcalf JL, Parfrey LW, Knight R. Defining the human microbiome. Nutr Rev. 2012;70(Suppl 1):S38–44.

- Chen T, Yu WH, Izard J, et al. The Human Oral Microbiome Database: a web accessible resource for investigating oral microbe taxonomic and genomic information. Database (Oxford). 2010;2010:baq013.

- Dewhirst FE, Chen T, Izard J, et al. The human oral microbiome. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:5002–5017.

- Kilian M, Chapple IL, Hannig M, et al. The oral microbiome—an update for oral healthcare professionals. Br Dent J. 2016;221:657–666.

- Olsen I. The oral microbiome in health and disease. Available at: http://scholar.google.com/scholar_url?url=https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ingar_Olsen2/publication/301264674_The_Oral_Microbiome_in_Health_and_Disease/links/575d101908aec91374abcc11/The-Oral-Microbiome-in-Health-and-Disease&hl=en&sa=X&scisig=AAGBfm1hTH_djklPnyHDZJF-BKb61KMwOA&nossl=1&oi=scholarr. Accessed November 23, 2019.

- Wade WG. Characterisation of the human oral microbiome. Journal of Oral Biosciences. 2013;55:143–148.

- Yamashita Y, Takeshita T. The oral microbiome and human health. J Oral Sci. 2017;59:201–206.

- Scannapieco FA. The oral microbiome: Its role in health and in oral and systemic infections. Clinical Microbiology Newsletter. 2013;35:163–169.

- Wade WG. The oral microbiome in health and disease. Pharmacol Res. 2013;69:137–143.

- Mason MR, Chambers S, Dabdoub SM, Thikkurissy S, Kumar PS. Characterizing oral microbial communities across dentition states and colonization niches. Microbiome. 2018;6:67.23.

- Boustedt K, Roswall J, Dahlén G, Dahlgren J, Twetman S. Salivary microflora and mode of delivery: a prospective case control study. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15:155.

- Zaura E, Nicu EA, Krom BP, Keijser BJ. Acquiring and maintaining a normal oral microbiome: current perspective. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014;4:85.

- Ferretti P, Pasolli E, Tett A, et al. Mother-to-infant microbial transmission from different body sites shapes the developing infant gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;24:133–145.

- Aagaard K, Ma J, Antony KM, et al. The placenta harbors a unique microbiome. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:237.

- Li Y, Caufield PW, Dasanayake AP, Wiener HW, Vermund SH. Mode of delivery and other maternal factors influence the acquisition of Streptococcus mutans in infants. J Dent Res. 2005;84:806–811.

- Holgerson PL, Vestman NR, Claesson R, et al. Oral microbial profile discriminates breast-fed from formula-fed infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:127–136.

- Scholz F, Badgley BD, Sadowsky MJ, Kaplan DH. Immune mediated shaping of microflora community composition depends on barrier site. PLoS One. 2014;9:e84019.

- Mouradian WE, Lewis CW, Berg JH. Integration of dentistry and medicine and the dentist of the future: the need for the health care team. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2014;42:687–696.

- Mouradian WE, Berg JH, Somerman MJ. Addressing disparities through dental-medical collaborations, part 1. The role of cultural competency in health disparities: training of primary care medical practitioners in children’s oral health. J Dent Educ. 2003;67:860–868.

- Lee SM, Kim HN, Lee JH, Kim JB. Association between maternal and child oral health and dental caries in Korea. J Public Health. 2018;27:219–227.

- Dragan IF, Veglia V, Geisinger ML, Alexander DC. Dental care as a safe and essential part of a healthy pregnancy. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2018;39:86–91.

- Kikuchi K, Okawa S, Zamawe CO, et al. Effectiveness of continuum of care-linking pre-pregnancy care and pregnancy care to improve neonatal and perinatal mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0164965.

- Kumar J, Iida H. Oral Health Care During Pregnancy—a Summary of Practice Guidelines. Available at: mchoralhealth.org/PDFs/OralHealthPregnancyConsensus.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2019.

- Oral Health Care During Pregnancy Expert Workgroup. Oral Health Care During Pregnancy: A National Consensus Statement. Washington, DC: National Maternal and Child Oral Health Resource Center; 2012.

- Vamos CA, Walsh ML, Thompson E, et al. Oral-systemic health during pregnancy: exploring prenatal and oral health providers’ information, motivation and behavioral skills. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:1263–1275.

- Steinberg BJ, Hilton IV, Iida H, Samelson R. Oral health and dental care during pregnancy. Dent Clin North Am. 2013;57:195–210.

- Figuero E, Carrillo-de-Albornoz A, Martin C, Tobias A, Herrera D. Effect of pregnancy on gingival inflammation in systemically healthy women: a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40:457–473.

- Geisinger ML, Geurs NC, Bain JL, et al. Oral health education and therapy reduces gingivitis during pregnancy. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41:141–148.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. December 2019;17(11):26–29.