YABUSAKA DESIGN/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

YABUSAKA DESIGN/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Preventing HPV-Related Infections

Oral health professionals must be knowledgeable about the human papillomavirus and its vaccine to effectively educate their patients.

This course was published in the December 2019 issue and expires December 2022. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the methods of transmission and risk factors for the human papillomavirus (HPV).

- Discuss the health issues caused by infection with HPV.

- Identify the role that oral health professionals play in improving HPV vaccination rates.

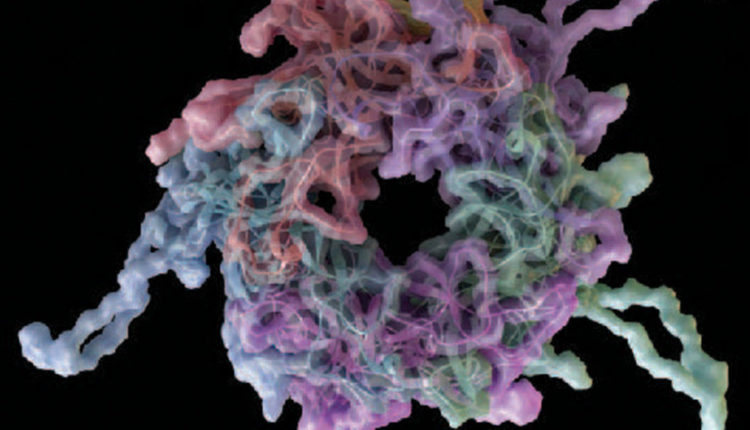

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a double-stranded DNA virus that only infects humans. It is a small, nonenveloped, capsid that initially infects the basal epithelial cells through microscopic breaks in the skin.1,2 It is the most commonly transmitted sexual infection and can cause a range of serious diseases, including the majority of cervical cancers, other anogenital cancers, and approximately half of head and neck cancers.3 The recent development of an HPV vaccine will help to decrease the spread of this virus and potentially prevent cancer. Oral health professionals need to be knowledgeable about the HPV vaccine so they can effectively educate their patients.

More than 200 different types of HPV have been described; they are classified as high-risk or low-risk depending on the frequency with which they cause cancer.4 The majority of HPV types are low risk and may cause benign oral epithelial lesions.5 HPV 16 and 18 are noted as high-risk, but new sampling methods have identified approximately 20 other high-risk types associated with oropharyngeal, cervical, anal, vulvar, and penile cancer.6,7

The vast majority of HPV infections resolve within 12 months, but persistent infections with high-risk types increase the likelihood of cytologic abnormalities progressing to precancerous or cancerous lesions. HPV can enter a latent state, but it is unknown if this is characteristic of all or only some types. It is also unknown if re-emergent HPV infections carry a greater risk of cancer in older adults.8 In women, the global prevalence of HPV is estimated at 11.7% with an estimated prevalence of 20 million infections in the United States.9,10 Prevalence rates for men are more difficult to estimate, as they are not routinely screened for HPV-related epithelial changes. The virus is extremely ubiquitous, and it is estimated that 80% to 100% of sexually active adults will be exposed to HPV in their lifetimes.2

While swabs of potentially infected sites are done for surveillance and research purposes, there is no Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved serological or blood test for HPV. Because most HPV infections are asymptomatic, the majority of HPV detection is limited to cervical cancer screenings done by a Papanicolaou test (pap smear) or biopsy of a known cancer. Currently, there is no equivalent test for oropharyngeal cancer. Testing of other anogenital sites, such as the anus, vagina, vulva, and penis, is rare. Therefore, the overall prevalence of this infection may be vastly underestimated.

METHODS OF TRANSMISSION AND RISK FACTORS

HPV is most commonly transmitted through sexual contact via oral, vaginal, or anal routes. Additionally, the virus can be vertically transmitted from mother to child during delivery or through breast milk. Nonsexual horizontal transmission can occur through close contact with family members or caregivers.11 The virus’s replication cycle is tied to the differentiation and maturation of the keratinocyte cell. As the skin cell matures, the virus transcribes genes for replication and capsid packaging. Once the cell sloughs off, new HPV infectious virions are released for infection through skin-to-skin contact.2

The risk of contracting an anogenital HPV infection is greatest in the decade after sexual debut.11 Thus, the prevalence of anogenital HPV peaks around the age of sexual debut, but decreases after age 25. A second small increase is sometimes seen in some post-menopausal women, which may indicate the virus’s re-emergence from a latent state.8 The greatest risk factor for anogenital HPV infection in women and men is number of sexual partners.1 For both sexes, risk factors for oral HPV include number of sexual partners, past history of sexual behaviors (including oral sex), and smoking status.12 Oral HPV infection is more rare than anogenital infection and disproportionately affects men.10

HUMAN PAPILLOMAVIRUS-RELATED CONDITIONS

Typing of HPV is done through sample collection with genetic analysis and impacts disease presentation.13 Noncancer HPV-related conditions include nongenital and genital warts (associated with HPV 6 and 11), recurrent respiratory papillomatosis in children, Bowen disease, and epidermodysplasia verruciformis (associated with HPV 5 and 8).1 Low-risk HPV types are also responsible for benign epithelial changes in the oral cavity, including verruca vulgaris, condyloma acuminatum, squamous papilloma, and multifocal epithelial hyperplasia.5 They present with a variety of morphologies including wart-like lesions, clustered rough or cauliflower-like exophytic lesions, or smooth dome-shaped papules. Most of these lesions are solitary and found throughout the oral cavity on the palate, tongue, lip vermillion, and labial mucosa.

High-risk oncogenic HPV types are linked to almost all cases of cervical cancer with HPV 16 associated with 50% of cases, HPV 18 associated with 20% of cases, and five other oncogenic HPV types associated with the remainder.14 HPV 16 is the type most strongly related to HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer.12

HUMAN PAPILLOMAVIRUS-RELATED OROPHARYNGEAL CANCER

Head and neck cancers occur in the oral cavity, larynx, and oropharynx, which include the tonsillar region and base of the tongue. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common type of head and neck cancer. Risk factors have traditionally included tobacco and alcohol use. After decades of declining head and neck cancer incidence due to decreased smoking and tobacco-use, there has been a recent and alarming uptick in HPV-related oropharyngeal cancers (HPV-OPSCC).3

From 1988 to 2015, a 225% population increase in HPV-OPSCC occurred in the United States while there was a simultaneous 50% decrease in non-HPV related OPSCC.15 This increase is particularly dramatic among healthy, nonsmoking white men and women younger than age 50—groups that were previously considered at low risk for developing oropharyngeal cancer.16 Detection of oropharyngeal cancer is somewhat difficult as the area is hard to visualize and signs and symptoms like a sore throat or difficulty swallowing may be mistaken for other conditions.

In this generally healthy population, care is often sought only after identification of nodal involvement. Oral health professionals are often the first health care providers to recognize an oropharyngeal lesion. Treatment for early-stage (no metastases beyond lymph nodes) oropharyngeal cancer includes chemotherapy with targeted radiation. Significant side effects during treatment include loss of taste sensation, permanent xerostomia, and potentially severe dysphagia necessitating a gastronomy tube. Prognosis for an early-stage diagnosis is quite good with overall survival rates of 95%.3 Despite this, there are significant morbidities associated with oropharyngeal cancer and its treatment in young adults including decreased quality of life, impacts on speech and masticatory function, need for lifelong surveillance, infertility associated with chemotherapy treatments, and high levels of anxiety and depression. For late-stage or oropharyngeal cancers that have metastasized or experienced a recurrence, the prognosis is poor.17

VACCINATION

Prevention of HPV infection includes sexual abstinence or delaying sexual contact, monogamy, using condoms or dental dams, and vaccination against both high- and low-risk subtypes. Vaccines for HPV have been available since 2006 for females and 2009 for males. Studies show the vaccine is safe and 90% to 100% effective in preventing infection and anogenital precancerous lesions.18 Currently, Gardisil 9 is the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved vaccine in the US for females and males. It is a nonavalent vaccine that targets HPV 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 59.19

The original age range for vaccination included children and adolescents ages 9 to 26 with a recommended two-dose schedule when vaccination was initiated between ages 9 and 14 and a three-dose schedule when initiated between ages 15 and 26. Individuals in the younger age group tend to elicit a higher immune response and therefore need fewer doses. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends an interval of 6 months between the two-dose and intervals of 1 to 2 months and 6 months for the three-dose schedules.20 In October 2018, the FDA approved Gardisil 9 for women and men ages 27 to 45.

The vaccine is useful for individuals previously infected with HPV as it may prevent strains they have not contracted, but it does not treat current HPV infections. Routine vaccination for individuals older than 26 is not recommended, however they are encouraged to discuss their risk of HPV infection with their primary care providers.19 Evidence from the earliest cohorts to receive the vaccine show a 10-year effectiveness of 88.2%.21 As the vaccine is relatively new, long-term effectiveness data are not available and susceptible populations may need a booster if antibody titers decline.

As awareness has grown, HPV vaccination rates have also increased, but lag behind other common childhood vaccinations. In 2016, uptake was 43% for females and 32% for males, both metrics that lagged behind the Health People 2020 target of 80%.20 Reasons for low HPV vaccination rates include lack of knowledge of HPV and the vaccine, concerns regarding vaccine safety and efficacy, financial barriers, and lack of timely, strong provider recommendation, particularly for males.22,23 Perhaps the most influential predictor of vaccination is the quality of provider recommendation.22 High-quality provider communication is timely, consistent, focuses on cancer prevention rather than mode of transmission, and includes a strong vaccine endorsement.22

THE ROLE OF ORAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

An integrated, multi-level, interprofessional approach to vaccine advocacy can increase utilization. Oral health professionals are strongly positioned to influence vaccination rates. In 2016, 84.6% of children ages 2 to 17 had at least one visit to the dentist during the year.23 This presents an opportunity for oral health professionals to educate patients about the HPV link to oropharyngeal cancer, risk factors, and prevention. However, clinicians must be informed and prepared to answer questions from patients. Forging collaboration with other health care providers can facilitate referrals for vaccination.

Chairside health screenings have become standard of care in the dental practice for systemic conditions, including hypertension, diabetes, tobacco/substance use, human immunodeficiency virus, nutrition, and head and neck cancers.24,25 Screening for HPV-OPSCC can easily be incorporated into a head and neck exam, however oral health professionals must understand the epidemiology, risk factors, signs, and symptoms associated with HPV-OPSCC to facilitate early detection. Yet, the characteristics of HPV-OPSCC complicate early detection. The anatomic location of HPV-OPSCC makes visualization difficult and the tonsillar crypts can hide the primary tumors. Further complicating early detection is the lack of an identified premalignant lesion and the prolonged asymptomatic phase associated with HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers. As a result, metastases to regional lymph nodes is common, and often a neck mass is the first clinical sign of HPV-OPSCC.26 Oral health professionals must palpate lymph nodes during head and neck exams and question patients about signs and symptoms. Several screening questions added to the medical history form may help to identify potential symptoms (Table 1). Asking routine questions regarding vaccination status can trigger a conversation on the role of HPV in oropharyngeal cancer and serve as a reminder for parents to initiate or complete the vaccination series for their children.

![Signs of HPV-related cancers]() COMMUNICATION IS KEY

COMMUNICATION IS KEY

Various messaging techniques are effective in facilitating patient/provider communication, including clinical decision support systems, fact sheets, patient education videos, and provider communication training.22

Motivational interviewing (MI), an evidence-based communication philosophy, has been shown to facilitate change in health behaviors such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, tobacco cessation, and oral hygiene.27,28 It has also been used to effectively facilitate HPV conversations in medical and pharmacy settings.22 MI can be most helpful in conversations with parents who are ambivalent about receiving the HPV vaccine. The essence of MI is patient-centered, collaborative care focusing on the ambivalence of change and facilitating the discovery of a person’s motivating factors.27 Using MI strategies improves the skills, comfort, and confidence of providers in having difficult conversations with patients, such as in delivering HPV messages.29

However, using MI to communicate with patients does not come naturally. Specific communication skills are required, including asking open-ended questions (What do you know about HPV and the link to throat cancer?); affirming (Safety of the vaccine is a real concern for you); reflective listening (I heard you say you want to prevent cancer, but you need more time to think about the vaccine); summarizing (After our discussion, I understand you are ready to have your child vaccinated. May I check in with you in 6 months regarding your child’s vaccination status?); and advising with patient permission (May I share some information about the HPV vaccine?).27

ADVOCACY OUTSIDE OF THE OPERATORY

There are multiple opportunities for oral health professionals to help improve awareness and prevention of HPV-related oral cancers. The National HPV Vaccination Roundtable has opportunities to become involved at various local or state levels. The Oral Cancer Foundation will provide free promotional materials for dental practices and organizations that offer free visual and tactile screenings during Oral Cancer Awareness Month in April.

Additionally, providing educational seminars for local schools and parent-teacher organizations can increase awareness with low burden to busy practitioners. Looking to the future, dental clinics could serve as an alternative setting for patients to receive the HPV vaccine. This would be particularly convenient for adolescents younger than 15, who qualify for the two-dose series, given at a 6-month interval. For integrated medical/dental clinics, nurses are available to provide the vaccine during an adolescent’s 6-month dental recare appointment.

CONCLUSION

Incidence rates of HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer are increasing at alarming rates. Although a vaccine preventing HPV-related cancers and other infections has been available since 2006, national rates fall well below the Healthy People 2020 target goals. Oral health promotion is an ethical responsibility of oral health professionals. This includes educating patients about HPV infections and advocacy for the prophylactic vaccination of HPV infections. Research shows that HPV vaccine uptake can be improved with strong provider recommendation. Advocacy of the vaccine by oral health providers may prompt an increase in vaccine uptake among adolescents. Improved HPV knowledge and training in patient communication for oral health providers may increase prevention of HPV-related oral infections.

REFERENCES

- Kero K, Rautava J. HPV Infections in heterosexual couples: mechanisms and covariates of virus transmission. Acta Cytol. 2019;63:143–147.

- Wang SS, Hildesheim A. Chapter 5: Viral and host factors in human papillomavirus persistence and progression. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2003;7234:35–40.

- You EL, Henry M, Zeitouni AG. Human papillomavirus–associated oropharyngeal cancer: review of current evidence and management. Curr Oncol. 2019;26:119–123.

- Várnai AD, Bollmann M, Bánkfalvi Á, et al. The spectrum of cervical diseases induced by low-risk and undefined-risk HPVs: Implications for patient management. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:563–570.

- Piña AR, Fonseca FP, Pontes FSC, et al. Benign epithelial oral lesions—association with human papillomavirus. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2019;24:e290–e295.

- Schiffman M, Castle PE, Jeronimo J, Rodriguez AC, Wacholder S. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet. 2007;370:890–907.

- Michaud DS, Langevin SM, Eliot M, et al. High-risk HPV types and head and neck cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:1653–1661.

- Rositch AF, Burke AE, Viscidi RP, Silver MI, Chang K, Gravitt PE. Contributions of recent and past sexual partnerships on incident human papillomavirus detection: acquisition and reactivation in older women. Cancer Res. 2012;72:6183–6190.

- Dunne EF, Unger ER, Mcquillan G, Swan DC, Patel SS, Markowitz LE. Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. JAMA. 2015;297:813–819.

- Serrano B, Brotons M, Bosch FX, Bruni L. Epidemiology and burden of HPV-related disease. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;47:14–26.

- Winer RL, Hughes JP, Feng Q, et al. Condom use and the risk of genital human papillomavirus infection in young women. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2645–2654.

- Hernandez BY, Shvetsov YB, Goodman MT, et al. Reduced clearance of penile human papillomavirus infection in uncircumcised men. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1340–1343.

- D’Souza G, McNeel TS, Fakhry C. Understanding personal risk of oropharyngeal cancer: Risk-groups for oncogenic oral HPV infection and oropharyngeal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:3065–3069.

- De Villiers EM, Fauquet C, Broker TR, Bernard HU, Zur Hausen H. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2004;324:17–27.

- Pytynia KB, Dahlstrom KR, Sturgis EM. Epidemiology of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2014;50:380–386.

- Tota JE, Anderson WF, Coffey C, et al. Rising incidence of oral tongue cancer among white men and women in the United States, 1973–2012. Oral Oncol. 2017;67:146–152.

- Price KAR, Cohen EE. Current treatment options for metastatic head and neck cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2012;13:35–46.

- Gillison ML, Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Fakhry C. Epidemiology of human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3235–3242.

- Salvadori MI. Human papillomavirus vaccine for children and adolescents. Paediatr Child Heal. 2018;23:262–265.

- Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination—updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Available at: cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm6549a5.htm. Accessed November 20, 2019.

- Chaturvedi AK, Graubard BI, Broutian T, et al. Effect of prophylactic human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination on oral HPV infections among young adults in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:262–267.

- Dempsey AF, O’Leary ST. Human papillomavirus vaccination: narrative review of studies on how providers’ vaccine communication affects attitudes and uptake. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18:21–22.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Oral and Dental Health. Available at: cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/dental.htm. Accessed November 20, 2019.

- Davide SH, Santella AJ, Furnari W, Leuwaisee P, Cortell M, Krishnamachari B. Research patients ’ willingness to participate in rapid HIV testing: a pilot study in three New York City dental hygiene clinics. J Den Hyg. 2017;91:41–48.

- Russell SL, Greenblatt AP, Gomes D, et al. Toward implementing primary care at chairside: Developing a clinical decision support system for dental hygienists. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2015;15:145–151.

- McIlwain WR, Sood AJ, Nguyen, SA, Day, TA. Initial symptoms in patients with HPV-positive and HPV-negative oropharyngeal cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140:441–447.

- Miller W, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2013:482.

- Kopp SL, Ramseier CA, Ratka-Krüger P, Woelber JP. Motivational interviewing as an adjunct to periodontal therapy—a systematic review. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1–9.

- Reno JE, O’Leary S, Garrett K, et al. Improving provider communication about HPV vaccines for vaccine-hesitant parents through the use of motivational interviewing. J Health Commun. 2018;23:313–320.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. December 2019;17(11):30, 33–35.

COMMUNICATION IS KEY

COMMUNICATION IS KEY

Learned lots of new content!