Women’s Oral Health Across Life Stages

Grasping the impact of hormonal fluctuations on oral health is crucial for providing effective dental care to women throughout their lifetimes.

This course was published in the August/September 2024 issue and expires September 2027. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 010

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Explain the role of sex hormones in women’s systemic and oral health across different life stages.

- Identify the specific oral health issues associated with hormonal fluctuations during

puberty, menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause. - Discuss comprehensive treatment and preventive care plans for women based on their

hormonal status and life stage.

Chemical substances produced by cells, hormones have a unique and specific regulatory effect on various parts of the body.1 Sex hormones, specifically in women, fluctuate throughout the stages of life including puberty and menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause.2 Hormonal fluctuations may impact oral health and initiate changes to the oral mucosa.3

Beginning at puberty, the anterior pituitary gland secretes gonadotropins, which directly interact with the ovaries and begin the production and secretion of estrogen and progesterone, the main female sex hormones. The primary function of estrogen is the development of sex characteristics, uterine growth, and production of the most potent estrogen known as estradiol. Progesterone is known for its support during menstruation and creating a healthy environment in the uterus during pregnancy.4

These sex hormones have specific receptors in target tissues, including the periodontium. Estrogen and progesterone have shown a direct and indirect impact on the differentiation and growth of periodontal tissues and the proliferation of cells in periodontal tissues.5,6 Specifically in the gingiva, these hormones can change the effectiveness of the epithelium walls against bacteria, affect collagen maintenance and repair, and increase cellular growth in blood vessels, leading to increased bleeding and inflammation even without the presence of plaque.4-7

Puberty and Menstruation

The American Academy of Pediatrics defines adolescence in three age groups including: early (11-14), middle (15-17), and late (18-21).8,9 During adolescence, or the transition from childhood to adulthood, changes in rapid biological growth, endocrinal fluctuations, and mental/emotional growth occur.2 Specifically during the puberty phase, increased hormone levels can negatively impact gingival tissues and subgingival microbiome, leading to an increase in gingivitis.2,6,7,10 Elevated hormone levels can result in increased blood circulation in gingival tissues and create a sensitivity to local irritants such as bacterial biofilm.8,11 Even in the presence of a small amount of plaque biofilm, exaggerated inflammation is triggered due to sex hormones altering the gingival inflammatory response.4,10

Other oral health and overall health issues for adolescent patients include elevated risk for periodontal diseases and caries, poor oral hygiene and nutritional habits, eating disorders, and alcohol and drug use. Due to puberty’s multifaceted effects on adolescents, oral health professionals must have a comprehensive medical, dental, and social history for accurate diagnosis and treatment.10

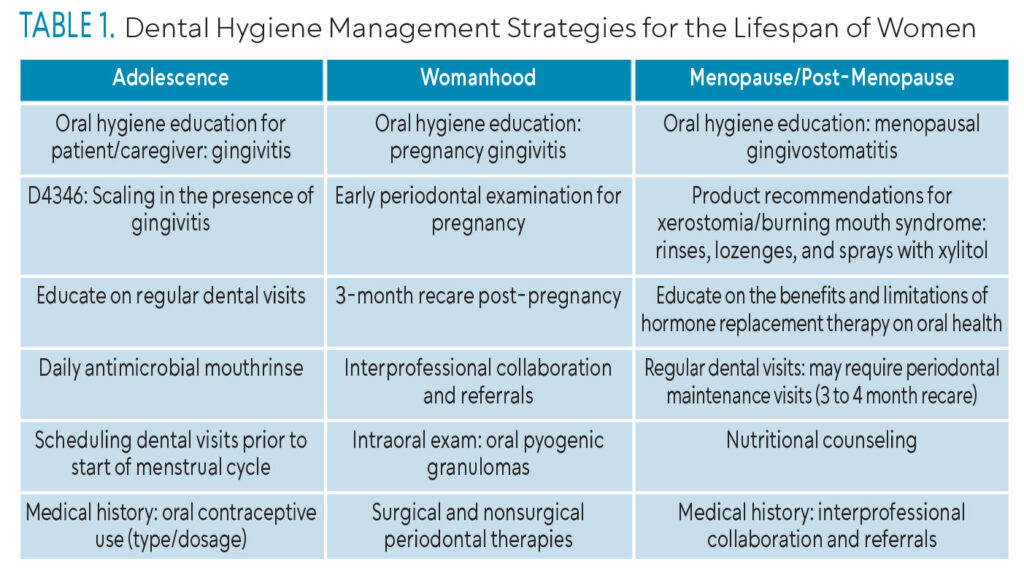

Treatment recommendations may include education on etiology of gingivitis to patient and caregiver, prevention measures for periodontal diseases, and instructions for adequate biofilm removal techniques through proper brushing and flossing.12,13 For those with moderate to severe gingivitis, scaling in the presence of gingivitis (D4346) may be considered in addition to a vigorous at-home oral hygiene program.7,8

During the menstrual cycle, sex hormones are secreted and estrogen levels rise to prepare the endometrium for pregnancy; if pregnancy does not occur, the estrogen levels will decrease and menstruation begins (4 to 6 days).5,8 Adolescence is when the first menstruation cycle typically begins.

In addition to puberty-induced changes, the gingival tissues are also negatively affected by hormones, specifically during the menstrual cycle, resulting in increased bleeding, exudation, and slight mobility.14 Adolescents also tend to experience irregular menstruation, excessive bleeding, and dysmenorrhea causing uterine cramps and pelvic pain, which may impact daily tasks, including oral self-care.2

Oral health professionals can educate these patients on the importance of proper oral self-care and regular dental visits to reduce the oral effects of hormone imbalance during menstruation.4,8 Additionally, an introduction of a daily antimicrobial mouthrinse and timing of dental hygiene recare visits prior to the start of a menstrual cycle may be indicated.7

Hormonal Contraceptives

Oral contraceptives (OCPs) are commonly known as “hormonal contraceptives” because many contain gonadotropin-releasing hormones (estrogen and progestin).7,8 Other forms of hormonal contraception include implantable rods, intramuscular injections, patches, rings, and sponges.8

Women using hormonal contraceptives should be aware of the influence and relationship to gingivitis and periodontal diseases. The presence of sex hormones within the contraceptives are associated with chronic gingivitis, which leads to excessive bleeding, erythema, and edema of the gingival tissues.4,7 Additionally, those using hormonal contraceptives may experience gingival hyperplasia, pigmentation of the oral mucosa, alveolar osteitis, and possible increase or decrease in salivary flow.15

The hormonal dosage and total duration of the contraceptive should be considered as the relationship is dose-dependent. For example, a patient with continual exposure to OCPs may have a higher risk for periodontal diseases compared to those with limited or no exposure.4,5,15 Many of the clinical features seen in patients taking OCPs are similar to those of pregnant women due to very high levels of sex hormones.16 Oral health professionals should document any contraception use and note any changes in type or dosage.8 Additionally, education on the importance of proper oral hygiene at home and regular dental visits are critical for patients taking hormonal contraceptives.

Pregnancy

During pregnancy healthy lifestyle practices are essential for both the mother and developing fetus.17,18 Hormonal shifts observed during pregnancy lead to changes in the immune system such as lowered T-cell activity, altered lymphocyte response, and decreased antibody production.5,7 Similar to the gingival effects during menstruation, pregnant women experience oral mucosa changes due to sex hormones, microbial flora, and presence of biofilm.5,18

The American Academy of Periodontology recommends that pregnant women undergo a thorough periodontal examination as early as possible in the pregnancy to treat and/or prevent negative oral mucosa changes and the systemic impacts.19 Additionally, it is safe for surgical and nonsurgical periodontal therapeutic services to be rendered to the pregnant patient.20

Oral health professionals play an important role in the maintenance and prevention of pregnancy-induced oral conditions through periodontal therapy services and oral hygiene education. Due to the gingival changes during pregnancy, daily oral self-care and regular professional dental care during and after pregnancy (3-month recare) are paramount.6,20 Medical providers should work interprofessionally with oral health professionals to ensure oral health examinations and preventive treatments are provided.17,19

Pregnant patients often experience pregnancy gingivitis and pyogenic granulomas. Up to 75% of pregnant women may develop pregnancy-induced gingivitis, which is caused by a change in the body’s natural response to bacterial biofilm due to hormonal changes.18,20,21 Clinically, the oral mucosa may appear with severe inflammation, enlargement, redness, and bleeding.20 Due to the likelihood of pregnant women developing gingivitis, periodontal examinations and oral hygiene self-care education should be provided early in pregnancy to prevent periodontal diseases.19

Research has shown a strong relationship between periodontal diseases and adverse pregnancy outcomes including preterm, low-birth weight babies, preeclampsia, and miscarriage.4,7,18,22,23 Oral pyogenic granulomas also referred to as “pregnancy epulis” or “pregnancy tumors” are common among pregnant patients. This lesion is not a tumor, but a painless rounded and isolated hyperplasia near the interdental area that appears smooth, shiny, purplish-red in color and bleeds easily.5,18,20 They are caused by the effects of progesterone and estrogen and their relationship to the host immune response and the vascularity of the gingival tissues.4,7 Oral health professionals should be prepared to treat pregnant patients presenting with these lesions with nonsurgical periodontal therapy to assist with inflammation and possible referral for excision and/or biopsy of lesion.4

Menopause and Post-Menopause

Menopause is when the complete and permanent cessation of the reproductive or menstrual cycle occurs.3 Typically, this occurs in women between the ages of 47 and 55; however, menopause may happen at earlier ages due to medical conditions and surgical procedures.

During menopause, the levels of estrogen and progesterone significantly decrease, signaling the end of fertility.8 Menopause is confirmed when a woman does not have a menstrual cycle for 12 consecutive months with no other possible causes.3 Several physiologic changes occur during this time including vasomotor reactions or “hot flashes,” mucosal changes (dryness and thinning of tissues), and emotional disturbances (mood swings, depression, difficulty with memory or concentration).8,24 Oral health is significantly impacted as well. Conditions may include menopausal gingivostomatitis, changes to mucous membranes and tongue, such as burning mouth syndrome (BMS), alveolar bone loss/periodontal diseases, osteoporosis, and potentially oral cancer.3,4,8,24,25

The oral mucosa and epithelium becomes thin, atrophic, and has decreased keratinizaton during menopause.7,8 These mucosal changes can lead to menopausal gingivostomatitis, which is characterized by shiny, dry, and pale mucosa that has a tendency to bleed easily.4,8,26

BMS is one of the most common oral complications found in menopausal and postmenopausal women.3,8 It causes burning or tingling sensation in the oral mucosa accompanied with an altered sense of taste and xerostomia, but no other identifiable abnormalities.3,8,27,28 The condition is often described as a burning sensation similar to burning the tongue on a hot cup of liquid with an altered or bitter taste sensation that typically gets worse throughout the day and extends for months to years at a time.25 Patients with BMS tend to struggle with mastication and nutrition due to these altered sensations. It is often treated with benzodiazepines, antidepressants, or analgesics.8,26

BMS-related xerostomia can be managed with salivary enhancements or substitutes found in mouthrinses, lozenges, and sprays with xylitol.3,26,29 Oral health professionals should provide adequate oral self-care education to help patients overcome the impacts of mucosal and salivary changes.

BMS-related xerostomia can be managed with salivary enhancements or substitutes found in mouthrinses, lozenges, and sprays with xylitol.3,26,29 Oral health professionals should provide adequate oral self-care education to help patients overcome the impacts of mucosal and salivary changes.

As estrogen declines in the body, systemic bone loss may occur, rendering the alveolar bone susceptible to accelerated resorption, resulting in periodontal diseases and often tooth loss.4,8,30,31 Osteoporosis and osteopenia are associated with alveolar bone loss , making them risk factors for periodontal diseases.32

The gold standard for women with osteoporosis is hormone replacement therapy (HRT), which replaces the decreased amount of estrogen and progesterone.4 Alternatively, medications, such as bisphosphonates (eg, alendronate), have also been used to treat osteoporosis. They focus on inhibiting bone resorption and reduce the incidence of bone fractures.27,30 Both HRT and bisphosphonate use may have positive effects on the periodontium including a reduced risk for periodontal diseases and improvement of soft and hard tissues.4,30 However, the use of bisphosphonates is linked to an increased risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw. This risk is influenced by the duration and potency of the drug, the method of administration (especially if given intravenously), and whether the patient has undergone recent dental surgery or has been diagnosed with cancer.30,33 Also, menopausal women using HRT are at a higher risk for oral cancer compared to men of the same age.24 Oral health professionals should ensure their patients with osteoporosis are managing their disease, removing bacterial biofilm with oral self-care strategies, and emphasizing the importance of regular dental hygiene visits.8,30

The gold standard for women with osteoporosis is hormone replacement therapy (HRT), which replaces the decreased amount of estrogen and progesterone.4 Alternatively, medications, such as bisphosphonates (eg, alendronate), have also been used to treat osteoporosis. They focus on inhibiting bone resorption and reduce the incidence of bone fractures.27,30 Both HRT and bisphosphonate use may have positive effects on the periodontium including a reduced risk for periodontal diseases and improvement of soft and hard tissues.4,30 However, the use of bisphosphonates is linked to an increased risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw. This risk is influenced by the duration and potency of the drug, the method of administration (especially if given intravenously), and whether the patient has undergone recent dental surgery or has been diagnosed with cancer.30,33 Also, menopausal women using HRT are at a higher risk for oral cancer compared to men of the same age.24 Oral health professionals should ensure their patients with osteoporosis are managing their disease, removing bacterial biofilm with oral self-care strategies, and emphasizing the importance of regular dental hygiene visits.8,30

Overall patient management for menopausal and post-menopausal women by oral health professionals should include regular dental and dental hygiene visits; daily oral self-care practices including interproximal care; eating a balanced diet; and no smoking.4,25,30 Additionally, an updated medical history is critical at this life stage due to the higher risk and incidence of other systemic conditions.8,30

Conclusion

Female sex hormones are unique to each life stage including adolescence, pregnancy, and menopause. Oral health professionals need to understand the hormonal changes occurring throughout women’s lives and the role sex hormones play in oral health to uniquely formulate comprehensive education and individualized treatment plans.

References

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hormone Disorders. Available at: cdc.g/v/nceh/tracking/topics/HormoneDisorders.htm. Accessed July 10, 2024.

- Gomes SR, Tamgadge S, Acharya S, et al. Awareness of oral health changes during menstruation: a questionnaire-based survey among adolescent girls. Dentistry and Medical Research. 2019;7(1);28-32.

- Dutt P, Chaudhary SR, Kumar P. Oral health and menopause: a comprehensive review on current knowledge and associated dental management. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3: 320-323.

- Sathish AK, Varghese J, Fernandes AJ. The impact of sex hormones on the periodontium during a woman’s lifetime: A concise-review update. Current Oral Health Reports. 2022;9:146-156.

- Markou E, Eleana B, Lazaros T, et al. The influence of sex steroid hormones on gingiva of women. Open Dent J. 2009;3:114-119.

- Patil SN, Kalburgi NB, Koregol AC, et al. Female sex hormones and periodontal health-awareness among gynecologists – a questionnaire survey. Saudi Dent J. 2012;24:99-104.

- Nirola A, Batra P, Kaur J. Ascendancy of sex hormones on periodontium during reproductive life cycle of womenJ J Intern Clin Dent Res Organ. 2018;10:3-11.

- Tolentino M. The patient with an endocrine condition. In: Boyd LD, Mallonee LF, eds. Wilkin’s Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 14th ed. Burlington, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Learning; 2023:987-997.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Adolescent Sexual Health. Stages of Adolescent Development. Available at: aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap -health-initiatives/adolescent-sexual-health/Pages/Stages -of-Adolescent-Development.aspx. Accessed July 11, 2024.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Classification of periodontal diseases in infants, children, adolescents, and individuals with special health care needs. Available at: aap/.org/research/oral-health-policies–recommendations/classification-of-periodontal-diseases-in-infants-children-adolescents-and-individuals-with-special-health-care-needs/. Accessed July 11, 2024.

- Thahir H, Savitry D, Akbar FH. Comparison of gingival health status in adolescents puberty in rural and urban. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2018;196: 1-6.

- Modeer T, Wondimu B. Periodontal diseases in children and adolescents. Dent Clin North Am. 2000;44:633-658.

- Grossi SG, Zambon JJ, Ho AW, et al. Assessment of risk for periodontal dJ ease. J Periodontol. 1994;65:260-267.

- Machtei EE, Mahler D, Sanduri H, et al. The effect of menstrual cycle on periodontal health. J Periodontol. 2004;75:408-412.

- Reddy P, Jamadar S, Chaitanya Babu N. Effects of oral contraceptives on the oral cavity. Indian J Dent Adv. 2013;5: 1274 6

- Farhad SZ, Esafahanian V, Mafi M, et al. Association between oral contraceptives use and interleukin-6 levels and periodontal health. J Periodontol Implant Dent. 2014;6:13-14.

- Oral Health Care During Pregnancy Expert Workgroup. Oral Health Care During Pregnancy: a National Consensus Statement. Available at: htt/s://mchoralhealth.org/PDFs/OralHealthPregnancyConcensus.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2024.

- Khanna S, Shalini M. Pregnancy and oral health: forgotten territory revisited! J Obstet Gynecol India. 2010;60:123-127.

- American Academy of Periodontology. Statement regarding periodontal management of the pregnant patient. J Periodontol. 2004;75:495.

- Rainchuso L. The pregnant patient and infant. In: Boyd LD, Mallonee LF eds. Wilkin’s Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 14th ed. Burlington, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Learning; 2023:839-858.

- Vamos CA, Cayama Richardson M, Mahony H, et al. Oral health during pregnancy: An analysis of interprofessional guideline awareness and practice behaviors among prenatal and oral health providers. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2023;23(721): 1-11.

- Daalderop LA, Wieland BV, Tomsin K, et al. Periodontal disease and pregnancy outcomes: overview of systematic reviews. JDR Clin Transl Res. 2018;3:10-27.

- Komine-Aizawa S, Aizawa S, Hayakawa S. Periodontal diseases and adverse pregnancy outcomes. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2019;45:5-12.

- Yuk JS, Kim BY. Relationship between menopausal hormone therapy and oral cancer: A cohort study based on health insurance database in South Korea. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1-10.

- Grover CM, More VM, Singh N, et al. Crosstalk between hormones and oral health in the mid-life of women: a comprehensive review. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2014;4:5-10.

- Mutneja P, Dhawan P, Raina A, et al. Menopause and the oral cavity. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16: 548-551.

- Suri V, Suri V. Menopause and oral health. J Midlife Health. 2014;5: 115-120.

- Meurman JH, Tarkkila L, Tiitinen A. The menopause and oral health. Maturitas. 2009;63:56-62.

- Gill N, Ruparelia P, Verma O, et al. Comparative evaluation of unstimulated whole salivary flow rate and oral symptoms in healthy premenopausal and postmenopausal women – An observational study. Journal of Indian Academy of Oral Medicine and Radiology. 2019;31(3):234-238.

- Buencamino MC, Palomo L, Thacker H. How menopause affects oral health, and what we can do about it. Cleveland Clinic J Med. 2009;76:467-475.

- Juluri R, Prashanth E, Gopalakrishnan D, et al. Associations of postmenopausal osteoporosis and periodontal disease: a double-blind case control study. J Int Oral Health. 2015;7:119-123.

- American Dental Association Council on Access, Prevention, and Interprofessional Relations. Women’s Oral Health Issues. Available at: https://ebusiness.ada.org/Assets/docs/뚹.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2024.

- Advisory Task Force on Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 2007;65:369-376.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. August/September 2024; 22(5):32-35