Understanding Altered Passive Eruption

Explore the diagnosis and treatment of APE, comparing conventional and digital methods to achieve optimal patient outcomes.

This course was published in the August/September 2024 issue and expires September 2027. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 490

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define altered passive eruption (APE).

- Identify the differences between treatment plans for APE.

- Discuss the role of the dental hygienist in treating patients with APE.

Eruption is defined as the movement of the tooth from its developmental site in the alveolar bone to its functional position in the oral cavity. The process of eruption is a continuous process. Several eruption theories have been developed that may explain the process of altered passive eruption (APE). The active and passive phases are the two main types of tooth eruption that occur.1

Active eruption describes the movement of the tooth from the developmental site to its functional position. In passive eruption, an apical migration shift of the dentogingival junction occurs.1 APE is defined as an esthetically impaired relationship between teeth, alveolar bone, and soft tissue frequently associated with excessive gingival display (EGD).

EGD presents as a gummy smile and short clinical crowns (Figure 1).2,3 Patients may desire correction of this gingival margin, or the most apical point of the margin (gingal zenith) discrepancy in order to achieve a more harmonious smile in terms of clinical crown dimensions.

As of 2018, the prevalence of APE is estimated to be approximately 12% in a group with more than 1,000 adults.4 A patient’s gingival phenotype is also correlated with APE. Typically, the prevalence is slightly higher among patients with a thick-flat gingival phenotype compared to patients who have a thick-scalloped phenotype or a thin-scalloped phenotype.5

While APE is underdiagnosed, patients often complain of a gummy smile due to EGD. While a gummy smile is a good indicator of APE, several steps must be considered when diagnosing APE and determining its etiological factors. A gummy smile may be associated with vertical maxillary growth, dentoalveolar extrusion, short upper lip, and upper lip hyperactivity.3 To correctly assess a gummy smile, a thorough diagnostic process must be done to determine whether conventional or digital methods of treatment planning are best.

gingival zeniths and short clinical crowns 6, 7, 10, and 11.

Diagnosis and Decision Making

The classification of APE focuses on case types and subcategories. The Coslet classification of APE includes type 1A, type 1B, type 2A, and type 2B (Figure 2).6 These case types are based on both gingival and osseous relationships. In a type 1 relationship, a wide band of keratinized gingiva is present (> 2 mm), whereas in a type 2 relationship, the keratinized tissue width is ≤ 2 mm.

In subcategory A cases, the osseous crest is located 1.5 mm to 2 mm below the cementoenamal junction (CEJ) while those in subcategory B include clinical situations where the osseous crest is found directly adjacent to, and sometimes overlapping, the CEJ.7 Overall, correct classification is critical when it comes to selecting the appropriate treatment plan for patients.

In subcategory A cases, the osseous crest is located 1.5 mm to 2 mm below the cementoenamal junction (CEJ) while those in subcategory B include clinical situations where the osseous crest is found directly adjacent to, and sometimes overlapping, the CEJ.7 Overall, correct classification is critical when it comes to selecting the appropriate treatment plan for patients.

APE’s diagnostic process includes the patient’s medical history, facial analysis, lip analysis, rest position analysis, dental analysis, and comprehensive periodontal examination. The patient’s medical conditions should always be evaluated, as they can significantly influence the suitability of various treatment options.

Facial analysis can indicate vertical maxillary excess (VME), the most common indicator of the appearance of EGD. In moderate to extreme VME cases, the patient will require orthognathic surgery, possibly in combination with periodontal surgery for anatomic crown exposure.2

Lip analysis should be considered. The appearance of EGD may be due to lip length and hypermobility of the lip, so the upper lip should be analyzed in both static and dynamic positions.2

An initial periodontal exam should be used to assess the health of the periodontium. A periodontal analysis can assess if the gummy smile appearance could be due to inflammation, gingival hyperplasia, or APE.2 Before any treatment is done, clinicians should present all options including risks, benefits, and alternatives.

Conventional Methods

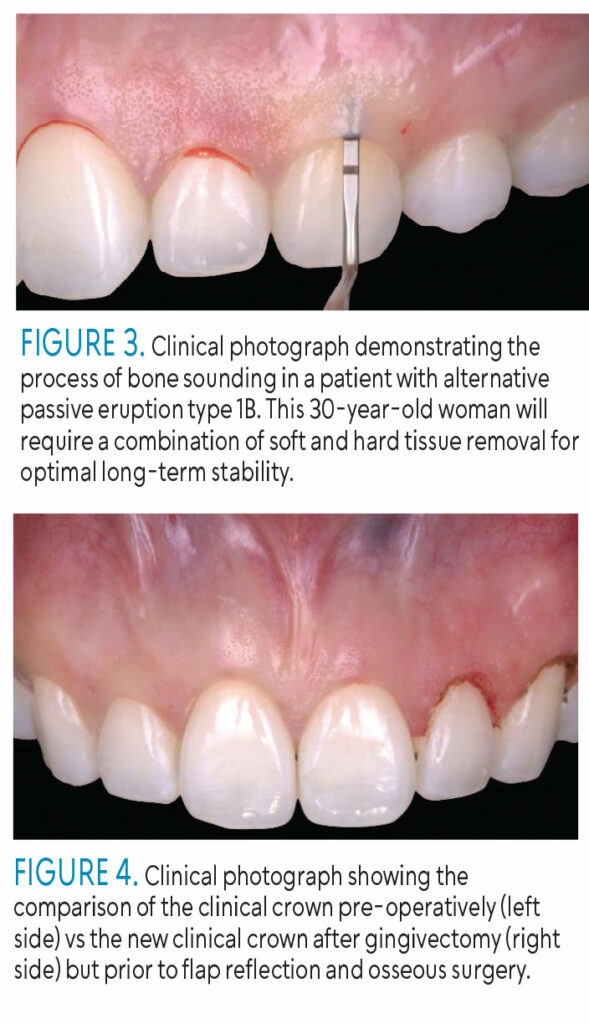

Treatment planning for APE includes clinical assessments and radiographic assessments, and both are used for detecting the location of the CEJ and assessing the alveolar bone crest.8 Various techniques can be used to guide the treatment of APE including bleeding points, or bone sounding (Figure 3), Chu’s proportion gauges, and laboratory-fabricated surgical guides or mock-ups.

In the bone sounding method, bleeding points are made when the clinician pierces through gingival tissues with a periodontal probe, connecting the punctures to show the future gingival outline.8

Chu’s proportion gauge combines a T-bar and in-line gauges, where the incisal edge rests on a platform. The height measurement is determined by matching the width of the tooth to corresponding color markings.8,9 A laboratory-fabricated surgical guide or a mock-up requires a wax-up, is made using vacuum formers or acrylic, and placed directly on the patient’s teeth.9,10 This can give the patient a clear visual representation.

Lastly, plastic retainers are commonly used as a surgical guide as they are easily fabricated, clear, and made of a rigid material.9 Conventional methods of planning in the treatment of APE are still currently used and can produce successful results (Figure 4).

![]() Digital Planning Methods

Digital Planning Methods

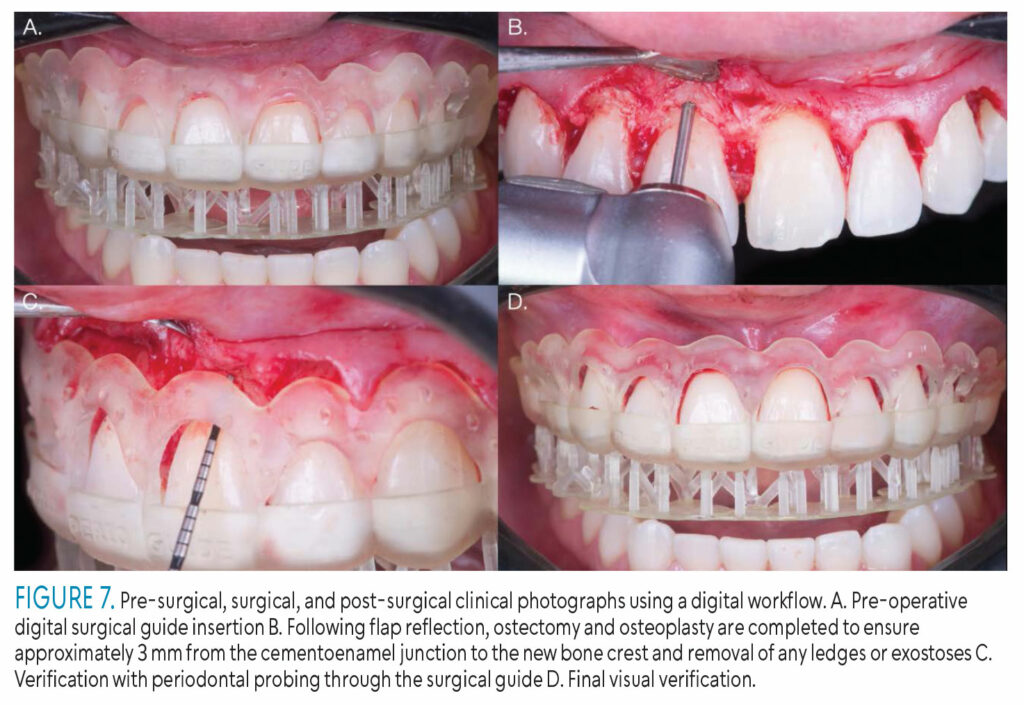

Advances in technology have impacted treatment for APE. Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) and computer software programs are now integral in its treatment. CBCT serves as a surgical guide by precisely measuring distances such as the anatomical crown length, gingival margin, and CEJ. This enables accurate planning to determine the necessary amount of gingival tissue to be removed (Figure 5).11

Advances in technology have impacted treatment for APE. Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) and computer software programs are now integral in its treatment. CBCT serves as a surgical guide by precisely measuring distances such as the anatomical crown length, gingival margin, and CEJ. This enables accurate planning to determine the necessary amount of gingival tissue to be removed (Figure 5).11

Multifunctional anatomical prototypes (MAPs) are a digital method of constructing a surgical guide. Computer software offering a digital/virtual smile design application (DSD) provides analysis of facial and dental characteristics that can strengthen diagnostics, increase treatment predictability, and provide digital templates of the patient that demonstrate final treatment results (Figure 6).12

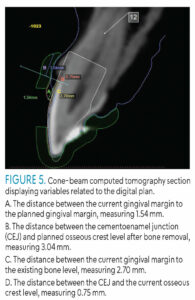

The ideal margin must be located first to create a dual guide. The lower margin closer to the CEJ will show where to extend the gingivectomy, and the higher margin closer to bone will demonstrate where to extend the bone removal to prevent soft tissue rebound.9

The ideal margin must be located first to create a dual guide. The lower margin closer to the CEJ will show where to extend the gingivectomy, and the higher margin closer to bone will demonstrate where to extend the bone removal to prevent soft tissue rebound.9

The guided dual technique is an extension to the dual guide method. In this technique, a digital impression is taken by an intraoral scanner camera. Computer-aided design, computer-aided manufacturing, DSD, and soft tissue CBCT measurements are used to create a three-dimensional (3D) digital model and a surgical guide on a 3D printer.12 The patient can then try on the 3D-printed MAP to visualize post-surgery results (Figure 7).13

![]() Outcomes of Conventional Vs Digital Methods

Outcomes of Conventional Vs Digital Methods

Both conventional and digital methods of treatment planning for APE are effective. Conventional methods in the planning of the treatment of APE are still widely used. In the bone sounding method, loss of interdental attachment is a concern.8 Chu’s proportion gauges can predict post-surgical outcomes; however, they should not be used if severe wear is present on the incisal edges.8 Laboratory-fabricated surgical guides are best suited for patients with severe wear of anterior teeth and those who do not need restorative treatment.8 Plastic retainers are only effective when they are made from a specific rigid material, fit well, are transparent, have ideal margins, and maintain proper interproximal contact.9 Using a mock-up offers benefits such as creating a smooth margin with its material and maintaining the natural tooth shape. However, a mock-up can break easily, and if it does during a surgical procedure, it cannot be used for bone reduction.9

Digital methods for APE treatment allow for more custom-made surgical guides that consider a patient’s anatomic crowns and enable clinicians to choose the most effective surgical approach based on patient characteristics.14 While CBCT shows significant potential by allowing measurement of both soft and hard tissues, it is susceptible to inconsistencies due to tooth positioning in the arch and technical issues.11

MAPs can be utilized in both the papillary area of the gingiva and the bone region, unlike traditional methods.13 Digital techniques reduce the risk of errors, improve visualization of the bone crest level, enhance patient communication, and prevent soft tissue recession and rebound during healing.12,15 However, digital techniques tend to take more time, increase costs, and result in unpredictable post-treatment esthetics.10,12

Treatment for APE includes the following: gingivectomy, crown lengthening procedure, orthognathic surgery, or a combination of these (Figure 8). If only a gingivectomy is performed rather than bone removal in subcategory B clinical scenarios (osseous crest is at the CEJ), soft tissue rebound is likely in the future. These procedures also carry the risk for minor changes in supracrestal tissue attachment, bone level, crown length, free gingival margin, clinical attachment level, and probing pocket depths.16 Choosing the surgical guide best suited for individual patient needs reduces the risk of these changes.

![]() Clinical Applicability to the Dental Hygienist

Clinical Applicability to the Dental Hygienist

Although surgical procedures are performed by dentists, the dental hygienist plays a crucial role in identifying these clinical presentations. This recognition aids in communicating with the dentist about potential treatments and determining if a referral to a periodontist is necessary. Dental hygienists can also educate patients on APE and its methods of treatment planning. Patients with APE frequently complain of a gummy smile, short teeth, or poor esthetics in general. By acknowledging and explaining the various causes of EGD, patients can gain a thorough understanding of their clinical condition and explore potential treatment options.

Conclusion

The choice between conventional and digital methods in treatment planning for APE differs from patient to patient; both methods are effective. The use of digital technologies can simplify the surgical guide fabrication process. Dental hygienists play an important role in this process due to their rapport with patients, which enables them to effectively educate patients. Both oral health professionals and patients with APE need to understand the pros and cons of treatment planning in order to achieve the most positive outcomes.

References

- Rabea AA. Recent advances in understanding theories of eruption (evidence based review article). Future Dent J. 2018;4:189-196.

- Dym H, Pierre R. Diagnosis and treatment approaches to a “gummy smile.” Dent Clin North Am. 2020;64:341-349.

- Ragghianti Zangrando MS, Veronesi GF, Cardoso MV, et al. Altered active and passive eruption: a modified classification. Clin Adv Periodontics. 2017;7:51-56.

- Mele M, Felice P, Sharma P, Mazzotti C, Bellone P, Zucchelli G. Esthetic treatment of altered passive eruption. Periodontol 2000. 2018;77:65-83.

- Nart J, Carrió N, Valles C, et al. Prevalence of altered passive eruption in orthodontically treated and untreated patientsJ J Periodontol. 2014;85:e348-e353.

- Coslet JG, Vanarsdall R, Weisgold A. Diagnosis and classification of delayed passive eruption of the dentogingival junction in the adult. Alpha Omegan. 1977;70:24-28.

- Pulliam R, Melker D. Altered Passive Eruption: Diagnosis and Treatment. Available at: glidewelldental.c/m/education/chairside-magazine/volume-4-issue-2/altered-passive-eruption-diagnosis-and-treatment. Accessed July 12, 2024.

- Alhumaidan A, al-Qarni F, AlSharief M, AlShammasi B, Albasry Z. Surgical guides for esthetic crown lengthening procedures. J Am Dent Assoc. 2022;153:31-38.

- Shi Y. Esthetic crown lengthening. Available at: youtube.com/watch?v=SWuY0KZuNQo. Accessed July 12, 2024.

- Alazmi SO. Three dimensional digitally designed surgical guides in esthetic crown lengthening: a clinical case report with 12 months follow up. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2022;14:55-59.

- Batista EL, Moreira CC, Batista FC, De Oliveira RR, Pereira KKY. Altered passive eruption diagnosis and treatment: a cone beam computed tomography-based reappraisal of the condition. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39:1089-1096.

- Carrera TMI, Freire AEN, De Oliveira GJPL, et al. Digital planning and guided dual technique in esthetic crown lengthening: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2022;27:1589-1603.

- Pedrinaci I, Calatrava J, Flores J, Hamilton A, Gallucci GO, Sanz M. Multifunctional anatomical prototypes ( MAPs ): Treatment of excessive gingival display due to altered passive eruption. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2023;35:1058-1067.

- Longo E, Frosecchi M, Marradi L, Signore A, de Angelis N. Guided periodontal surgery: a novel approach for the treatment of gummy smile. A case report. Int J Esthet Dent. 2019;14:384-392.

- Longo E, de Giovanni F, Napolitano F, Rossi R. Double guide concept: A new digital paradigm for the treatment of altered passive eruption in patients with high esthetic expectations. Int J Esthet Dent. 2022;17:254-265.

- Smith SC, Goh R, Ma S, Nogueira GR, Atieh M, Tawse-Smith A. Periodontal tissue changes after crown lengthening surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Saudi Dent J. 2023;35:294-304.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. August/September 2024; 22(5):36; 39-41