Screening for Sleep Problems

Dental hygienists can help improve their patients’ systemic health by noting the early symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea.

This course was published in the July 2012 issue and expires July 2015. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

- Name the physical characteristics, symptoms, and adverse systemic consequences associated with OSA.

- Recognize the oral complications associated with treatment of OSA.

- Explain treatment options for OSA in children and adults.

- Identify the role of the dental hygienist in the recognition and management of OSA.

Dental hygienists are trained to evaluate the entire patient and not just the oral cavity. Even with a limited appointment time, dental hygienists can recognize traits, characteristics, and behaviors that predispose patients to a variety of systemic conditions, including sleeping disorders. For example, when greeting your 10:00 am patient, you observe that the 60-year-old man’s head is down, his eyes are closed, and by the sound of his breathing, he is obviously napping. You call his name. Startled, he looks up and makes eye contact with you. As you review his medical history, you notice he is overweight with a thick neck circumference. During the intraoral assessment, his large tongue and uvula block the back of the oral cavity, impeding your view of the throat. His medical history reveals coronary artery disease and hypertension. Is there enough information to diagnose this patient with a sleeping disorder? Probably not, but this patient exhibits some risk factors of a sleeping disorder, such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Dental hygienists are becoming more familiar with screening questionnaires and assessments of the oropharyngeal anatomy that can be used to further evaluate the patient. If the patient presents with risk factors, the dental hygienist should make the dentist aware and possibly suggest a referral to the patient’s primary care physician for further evaluation and testing.

WHAT IS OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA?

OSA is a sudden blockage of air in the upper airway that occurs during sleep. These repeated pauses in breathing (apnea episodes) occur during sleep as the muscles of the body relax. Daytime sleepiness, fatigue, and snoring are symptoms. Many times patients are unaware of these apnea episodes and remain undiagnosed for years. OSA can cause other systemic health problems, such as arrhythmias, atherosclerosis, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, diabetes, hypertension, pulmonary hypertension, and stroke.1–3 OSA involves several components of the pharyngeal airway anatomy including the base of the tongue, soft palate, uvula, adenoids, tonsils, and nose. Nearly 80% of all moderate to severe cases of OSA in middle-aged men and women are undiagnosed.4 The dental professional can play an important role in the early detection, referral, and treatment of OSA.

OSA symptoms are noticeable during an oral assessment. A narrow palate can increase the risk by reducing the space for the tongue, causing crowding of the pharyngeal airway and reducing the nasal space. Enlarged uvula, tonsils, and adenoids may also lead to obstruction of the upper airway. Occlusal tendencies, such as a retrognathic profile and class II occlusion crossbite, also contribute to OSA. Additional intraoral features include dental attrition caused by bruxism and erosion related to gastroesophageal reflex disorder (GERD). Edentulism is also considered an OSA risk factor. The loss of vertical dimension resulting from the missing teeth may lead to the collapse of pharyngeal soft tissues.

Xerostomia is also a risk factor due to episodes of an open mouth during the night.5,6 Obesity is a symptom and 70% of patients with sleep apnea are obese.7 Studies show that neck circumference greater than 17 inches for men and 16 inches for women also raises the risk of OSA.8

DIAGNOSIS

The definitive diagnosis for OSA is achieved through a sleep study or polysomnogram that is typically performed in a sleep lab. Patients are required to spend approximately 8 hours at the lab under observation. During a sleep study, biophysiological changes are documented and recorded. The sleep study evaluates oxygen levels; snoring; respiratory effort; nasal and oral airflow; brain waves by electroencephalogram (EEG); heart activity by electrocardiogram (ECG); and eye, jaw, and leg movement through electromyogram (EMG). The sleep study measures apnea and hypopnea episodes. Apnea is a cessation of airflow of the upper airway lasting at least 10 seconds. Hypopneas are partial obstructions resulting in a 20% to 50% decrease in airflow. Both cause a decrease in oxygen and increase in carbon dioxide in the blood. The polysomnography technician closely monitors the patient during sleep, recording and evaluating the biophysiological changes that occur. If the polysomnography test indicates OSA, patients are given an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) score to classify the severity. A moderate to severe AHI score requires treatment.

SCREENING TOOLS

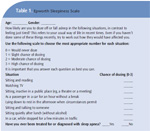

Screening tools can be utilized during the dental hygiene appointment to identify patients at risk of OSA. These include easily administered patient questionnaires and visual intraoral assessment. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale, a simple questionnaire regarding daytime sleepiness, is used to identify high risk patients (Table 1).9 A score is derived to confirm the patient’s risk of OSA and encourage the patient to schedule a more definitive examination, such as a full sleep study. STOP and STOP-BANG are acronyms used to identify significant risk factors of OSA, including snoring, fatigue, observed apneas, high blood pressure, BMI greater than 30, age (middle aged), neck circumference, and gender (Table 2).10,11 Visual intraoral assessments that measure soft tissue obstruction through a grading system are available, such as the Friedman, Fujita, and Mallampati scoring systems.12–16

One of the most common screening methods, the Mallampati classification, is used by anesthesiologists to identify patients who may be at risk for a difficult airway intubation during general anesthesia. Research has confirmed the usefulness of this scoring system in identifying patients who may also be at risk for OSA.15 Currently other health professionals, such as pulmonologists, physicians, and respiratory care practitioners, use this screening tool. The airway is classified by examining the oral cavity as the patient opens his or her mouth and extends the tongue. The dental hygienist can evaluate the opening of the oropharynx by comparing the size and shape of the soft palate and uvula to the back of the throat. Mallampati classifications of III or IV indicate the patient may be at risk for OSA. These classification systems are not used to diagnose OSA, but they do provide signals that additional testing is needed and help raise awareness among patients.

Not all patients exhibit the classic signs and symptoms of OSA. Women may present with symptoms different from the traditional symptoms of loud snoring, thick neck circumference, and daytime sleepiness. Women may experience symptoms such as morning headaches, fatigue, and mood disturbances that may not prompt further testing for a sleep disorder.

TREATMENT

A variety of treatment options are available for patients with OSA. Multidisciplinary approaches may include continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) devices, oral appliances, behavioral treatment, surgery, and/or adjunctive treatments.17 These options are based on the severity of the condition, patient’s age, medical history, and the cause of the obstruction. The most common treatment is the CPAP machine, which is used during sleep. A mask attached to a ventilating device is worn and delivers a continuous air flow to open the airway during sleep. Some patients refuse to use the CPAP device for various reasons. The pressure of the mask may be uncomfortable and the continuous airflow may cause xerostomia or even make the patient feel claustrophobic. For patients who do not accept the CPAP, alternative treatments should be considered. Secondary medical treatment for OSA includes oral appliances, surgery, and behavioral modifications. The anterior mandibular positioning (AMP) device is an oral appliance designed to reposition the mandible in a forward position. The device pulls the back of the tongue forward, helping to open the airway. Appliances are custom made and vary in design. When oral appliance therapy is used, a secondary poly somnography test is required to determine success of the treatment.

Side effects may occur with the use of AMP devices including tooth movement, excessive salivation, and temporomandibular joint pain that may limit their use. In severe cases, these appliances may be used in conjunction with CPAP. Surgical procedures may be recommended, including adenotonsilectomy (removal of adenoids and tonsils); uvulo palato pharyn geal plasty, which reduces the soft tissue in the oropharyngeal region; and maxilla mandibular advancement, which surgically lengthens the jaw. In very severe cases, a tracheotomy can be recommended, which will bypass the airway occlusion and alleviate the obstructive apneas. This treatment is usually done only if all other modalities have failed.

CHILDREN AND OSA

Sleep disorders also affect children. OSA can affect a child’s development and behavior and should be diagnosed and treated early. Enlarged tonsil tissues are one of the main causes. The increased size of the tonsil tissue may result in blockage of the airway and cause interruptions in breathing during sleep. Children with craniofacial anomalies, such as retrognathia or micrognathia, midface hypoplasia, mandibular hypoplasia, and macroglossia, may also be at risk for OSA.18 Risk factors among children include snoring or family history of OSA, cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, Down syndrome, sickle-cell disease, mouth breathing, nasal obstruction, and obesity.19 Nighttime symptoms include snoring, bizarre sleeping position, bedwetting, and sweating. Daytime symptoms include aggressive behavior, anxiety, hyperactivity, inattentiveness, learning difficulties, poor grades, morning headaches, mouth breathing, and a history of recurrent illness.20,21

Polysomnography sleep studies are also used to diagnose OSA in children. Surgery is the primary treatment in this patient population. Adenotonsilectomy results in eliminating OSA in 75% to 100% of cases.20 Oral appliances, such as the rapid maxillary expansion device (palatal expander), may also be used to allow the tongue more room in the oral cavity and reduce airway obstruction. Re-evaluation using polysomnography after surgery or other interventions may be necessary to determine the success of treatment.

ROLE OF THE DENTAL HYGIENIST

By completing a comprehensive exam, dental hygienists can provide a valuable service to their patients by incorporating the OSA Essentials for Dental Hygienists (Table 3), into their routine evaluation of every patient. Depending on the screening tools and methods used, the amount of time added to the dental hygiene appointment will fluctuate from patient to patient. Most patients show symptoms of disease before they are formally diagnosed. Nondescript symptoms tend to arise long before patients are motivated to pursue a medical diagnosis. All health professionals, including dental hygienists, should be participating in the screening and referral of patients with sleep disorders.22

REFERENCES

- Wolk R, Somers VK. Cardiovascular consequences of obstructive sleep apnea. Clin Chest Med. 2003;24:195–205.

- Lee W, Nagubadi S, Kryger MH, Mokhlesi B. Epidemiology of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: a Population-based Perspective. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2008;2:349–364.

- Patil SP, Schneider H, Schwartz AR, Smith PL. Adult obstructive sleep apnea: pathophysiology and diagnosis. Chest. 2007;132:325–337.

- Young T, Evans L, Finn L. Palta M. Estimation of the clinically diagnosed proportion of sleep apnea syndrome in middle-aged men and women. Sleep. 1997;20:705–706.

- Oksenberg A, Froom P, Melamed S. Dry mouth upon awakening in obstructive sleep apnea. J Sleep Res. 2006;15:317–320.

- Al Lawati NM, Patel SR, Ayas NT. Epidemiology, risk factors, and consequences of obstructive sleep apnea and short sleep duration. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;51:285–293.

- Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:97–111.

- Davies RJ, Stradling JR. The relationship between neck circumference, radiographic pharyngeal anatomy, and the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Eur Respir J. 1990;3:509–514.

- Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–545.

- Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:812–821 .

- Ong TH, Raudha S, Fook-Chong S, Lew N, Hsu AAL. Simplifying STOP-BANG: use of a simple questionnaire to screen for OSA in an Asian population. Sleep Breath. 2010;14:371–376.

- Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Bass L. Clinical staging for sleep-disordered breathing. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:13–21.

- Friedman M, Soans R, Gurpinar B, Lin HC, Joseph NJ. Interexaminer agreement of Friedman tongue positions for staging of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139:372–377.

- Shott SR. Pediatric obstructive sleep apnea base of tongue obstruction.Operative Techniques in Otolaryngoly. 2009;20(4):278–288.

- Nuckton TJ, Glidden DV, Browner WS, Claman DM. Physical examination: Mallampati score as an independent predictor of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2006;29:903–908.

- Liistro G, Rombaux P, Belge C, Dury M, Aubert G, Rodenstein DO. High Mallampati score and nasal obstruction are associated risk factors for obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:248–252.

- Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ Jr, et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:263–276.

- Alkhalil M, Lockey R. Pediatric obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) for the allergist: update on the assessment and management. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011;107:104–109.

- Capua M, Ahmadi N, Shapiro C. Overview of obstructive sleep apnea in children: exploring the role of dentists in diagnosis and treatment. J Can Dent Assoc. 2009;75:285–289.

- Section on Pediatric Pulmonology, Subcommittee on Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical practice guideline: diagnosis andmanagement of childhood obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Pediatrics. 2002;109:704–712.

- Bantu CS, Melgar, T, Patel D. Pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:81–85.

- Stanford University. Overview of the Findings of the National Commission on Sleep Disorders Research (1992). Available at: www.stanford.edu/~dement/overview-ncsdr.html. Accessed June 21, 2012.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. July 2012; 10(7): 56-59.