Safety Education

In light of well-publicized breaches in infection control protocols, oral health professionals should be prepared to reassure patients that dental care is safe.

Breaches in infection control protocol in the dental setting have made national news. While such instances are rare, publicized cases of these occurrences—including transmission of the hepatitis B virus (HBV) to patients and volunteers in a portable dental clinic1 and the first patient-to-patient transmission of hepatitis C (HCV) in a private dental practice2—can lead to patient concerns regarding infection control practices. Oral health professionals should be prepared to answer questions about their dental practice’s infection control program, as well as demonstrate relevant procedures, in order to quell patient fears.

SAFETY PROTOCOL

In the decades since oral health professionals began using universal and standard precautions—including the utilization of personal protective equipment and the safe handling of sharps—there has been only one documented outbreak (more than one transmission) of HBV in a dental setting in the United States.3 When this single instance is compared to the 35 outbreaks of HBV and HCV that occurred between 2008 and 2012 in other health care settings, the relative risk of patient-to-patient disease transmission in the dental operatory is low.4 Regardless of these statistics, however, the general public expects the delivery of oral care to be safe. For this reason, oral health professionals must reinforce their infection control protocol.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Healthcare Settings—2003 is the minimum standard of infection prevention and control for dental professionals and dental health care practice settings.5 Compliance with these guidelines, as well as other local, state, and federal regulations, is mandated for all providers and settings where oral care is provided. Actual compliance with CDC guidelines and other regulations can be impacted by many factors including: knowledge, experience, and commitment of the provider(s); comprehensive and understandable policies and procedures; and effective systems of implementation and oversight. To ease understanding of such policy, the CDC recommends that each dental practice develop a written infection control program based on proven principles of infection control to prevent or reduce the risk of disease transmission.5 A team member should be designated as the infection control coordinator and charged with implementing such policies and monitoring staff compliance.

CREATING A COMPREHENSIVE PLAN

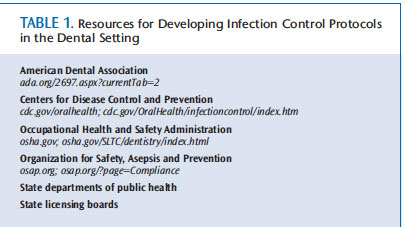

Review of the site-specific infection control program becomes a first step in reassuring patients they are safe in the dental practice’s care. A dental office’s comprehensive program should contain written policies and standard infection control protocols that are consistent with current CDC recommendations, Occupational Safety and Health Administration regulations, and other relevant state and local guidelines and statutes. See Table 1 for resources that may assist practices in the drafting of such programs.

ADDRESSING PATIENT CONCERNS

Oral health professionals should be prepared to answer patient questions about the office’s infection control program. The Organization for Safety, Asepsis and Prevention (OSAP) has prepared questions for patients to ask their dental care providers regarding infection control practices, including:

- Do you heat sterilize all of the instruments, including handpieces, between patients?

- How do you know that the sterilizer is working properly?

- Do you change your gloves for every patient?

- Do you disinfect the surfaces in the operatory between patients?

OSAP also advises patients who are unclear or uncomfortable with their dental practice’s safety precautions to speak with the dental team about their concerns, and also to request to see the office’s instrument processing area. Clinical answers to these patient questions are available at osap.org, and they reflect current dental infection control recommendations from OSAP and CDC, as well as the American Dental Association (ADA).

DEMONSTRATE A COMMITMENT TO SAFETY

There are several approaches to communicating the dental practice’s infection control program to patients. A common approach is the “tell, show, do” method. Tell by answering patient questions; show by providing patients with pamphlets or a video about infection control; and do by demonstrating various infection control activities in view of the patient. The resources listed in Table 1 also provide information on the development of practice-specific communications and training for patient education purposes.

The dental team should recognize that the waiting room is the first point of physical contact for the patient with the practice. Play a video and display pamphlets or a framed letter in the waiting room that describe the practice’s commitment to infection control procedures and safe dental care. Another strategy to engage patients in the practice’s infection control program is to post a “cough etiquette” sign, a box of tissues, waste receptacle, and hand sanitizer in the waiting room. The CDC offers “Cover Your Cough” signage on its website. Reinforce this message by placing handwashing signs in patient restrooms. Posting the annual participation certificate from the dental practice’s sterilization monitoring service is another tool to further communicate a commitment to an effective infection control program.

The dental operatory is where the patient observes the infection control program in action. To reinforce a commitment to infection control practices and safety, oral health professionals should don a facemask, eyewear, and lab coat, and wash their hands or use an alcohol-based hand rub prior to donning disposable gloves in front of the patient.

Patients also want to know that the items used in their mouths are sterile or single-use disposable items. Clinicians may demonstrate that instruments are sterilized by opening the package of instruments in front of the patient. This allows the patient to see the sterile pack of instruments, watch the clinician open it, and check the internal chemical indicator. The high- and slow-speed dental handpieces should be opened in front of the patient, as well.

Another demonstration technique is to keep the single-use patient care items on the tray, and place them on the various unit connections in front of the patient. If everything is set-up on the tray when the patient comes into the operatory, he or she has no way of knowing what processes the instruments have undergone.

The patient is generally not present in the dental operatory when it is cleaned and disinfected, or as surface barriers for environmental infection control are placed and secured. However, once seated, patients will observe such surface barriers and containers of liquid disinfectant/disinfectant wipes in the operatory. For patients with questions about how the operatory is aseptically prepared between patients, provide an explanation of the dental practice’s steps in setting up and breaking down the operatory. This includes details on why some surfaces are cleaned and disinfected while others are covered. Reassure patients that covers are replaced and other surfaces are cleaned and disinfected between every patient.

Other communication and demonstration approaches may be developed for the dental practice’s specific setting. Selected strategies should be written as policies and standard operating procedures in the infection prevention and control program manual or exposure control plan. These strategies should be consistently applied throughout the practice so the patient receives a congruent message.

CONCLUSION

The public trusts and expects that the delivery of dental care will be safe. This includes the prevention of infectious disease transmission. News stories about breaches in infection control and reports of disease transmission can jeopardize this trust. By clarifying that transmissions of infectious diseases are rare in the dental office, and through effectively communicating the dental practice’s infection control program, clinicians can reassure patients that dental care is indeed safe.

REFERENCES

- Radcliffe RA, Bixler D, Moorman A, et al. Hepatitis B virus transmissions associated with a portable dental clinic, West Virginia, 2009. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:1110–1118.

- Klevens RM, Moorman AC. Hepatitis C virus: An overview for dental health care providers. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:1340–1347.

- Redd JT, Baumbach J, Kohn W, Nainan O, Khristova M, Williams I. Patient-to-patient transmission of hepatitis B virus associated with oral surgery. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1311–1314.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare-Associated Hepatitis B and C Outbreaks Reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2008-2012. Available at: cdc.gov/hepatitis/ Outbreaks/HealthcareHepOutbreakTable.htm. Accessed December 26, 2013.

- Kohn WG, Collins AS, Cleveland JL, et al. Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings—2003. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52:1–61.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2014;12(1):28,30–31.