VLADRU/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

VLADRU/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Preventing Peri-Implantitis

How to develop an evidence-based plan for implant success.

This course was published in the September 2018 issue and expires September 30, 2021. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Explain the difference between peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantits.

- List the risks associated with peri-implant disease.

- Discuss the assessments needed to detect peri-implant disease.

- Describe the ideal maintenance schedule for a patient with an implant.

Dental implants are becoming more standard in replacing single or multiple teeth and are a predictable way of maintaining a healthy smile. There are an estimated 500,000 dental implants placed yearly in the United States.1 Placement has become more predictable with routine use of cone beam computed tomography and bone augmentation.2 Peri-implant care is becoming more common and requires the clinician and patient to maintain periodontal health for long-term success. Functional success of a dental implant includes that it has no mobility, absence of bleeding on probing, lack of peri-implant bone loss, and a probing depth < 5 mm.3 To increase longevity, the early signs and symptoms of peri-implant disease must be noted.

Stability is dependent on successful osseointegration or bone growth into the threads of an implant and a tight soft tissue biological seal. The biological seal is the soft tissue attachment via basal lamina and hemidesmosomes to the implant rather than collagen fibers. Circular and oblique collagen fibers function to adapt the gingival tissue to the implant.4 The presence of oral biofilm can infiltrate into the surrounding tissues easily and result in inflammation in the hard and soft tissues.5

Peri-implant disease has two manifestations: peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis. In December 2017, the Proceedings of the World Workshop on Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions were released.6 These definitions describe diagnostic criteria of implant disease. Peri-implant mucositis is inflammation in the surrounding gingival tissue with no signs of loss of supporting bone following initial placement.6 Peri-implantitis is a plaque-associated inflammatory disease occurring around a dental implant.6 Clinical signs of peri-implantitis are inflammation of the mucosa surrounding the dental implant and progressive bone loss.6 Bleeding on probing is the primary sign of inflammation.7 The prevalence of peri-implant mucositis is approximately 48% of implants 9 years to 14 years after placement.7 Peri-implantitis prevalence is difficult to determine due to the differing criteria used in studies.7 Patients who had periodontitis before placement have a higher occurrence of peri-implantitis.7 Peri-implant mucositis is a precursor to peri-implantitis, like gingivitis is a precursor to periodontitis. Peri-implant mucositis must be treated to reduce the risk of progression to peri-implantitis.7

ASSESSMENTS

Assessment of the dental implant is an essential part of the dental hygiene care plan. Clinical signs of inflammation must be included in evaluating the implant at each appointment. Early detection of inflammatory disease is the best method for prevention and contributes to successful outcomes. Any redness, enlarged tissue, and suppuration should be noted and seen as a sign of peri-implant disease. Mobility of a dental implant is considered a failed implant, as the threads should be osseointegrated, which does not allow for any movement. The presence of biofilm and calculus accumulation needs to be noted. Biofilm indicates high risk for an inflammatory reaction and must be removed.8 Any evidence of threads is a sign of implant complications—only the abutment should be visible. When evaluating dental implants, clinicians must look for occlusal problems. These may manifest as a broken or cracked prosthesis or occlusal wear on crown. Occlusion may need to be adjusted or an occlusal guard should be fabricated.8

Probing dental implants is somewhat controversial, however, probing is the preferred method of determining the integrity of soft tissue, both in implants and natural teeth.8–12 Probing an implant provides limited information compared with probing a natural tooth, as it depends on the thickness of the probe, insertion angle, the force of insertion, and the design of the prosthesis. Bone remodeling is normal after placement. Pockets up to 4 mm can be considered healthy if there is no bleeding on probing or inflammation.10 Bleeding on probing is a strong indicator of active disease and therefore probing is necessary to diagnose peri-implant mucositis early.10,11 The lack of bleeding on probing indicates periodontal health. Traditionally a plastic probe has been used to measure attachment loss. Fakhravar et al11 discovered in an in vitro study that metal probes seem to have no effect on the abutment surface while the plastic probe may cause surface roughness. The key to successful probing of an implant is to use very light pressure.10,12 An increase in probing depths may indicate the loss of bone and should be evaluated for surgical treatment. Probing should be performed at the final prosthesis placement and at least yearly thereafter.10

A periapical radiograph should be taken yearly to assess bone loss. Ideally, the radiograph should be taken at the same angle to be able to determine bone loss accurately.9 The purpose of a radiograph is to evaluate the height of the bone, quality of the bone around and along the length of the implant, and to detect any radiolucencies.10 All threads should be integrated into the bone and no horizontal or vertical bone defects should be present (Figure 1). Bone loss in the anterior region will also affect esthetics (Figure 2). In a radiograph, a vertical distance of 2 mm or greater from the original crestal bone level can be considered peri-implantitis.9 Long-term assessment of the dental implant should not be based on radiographs alone, but should include probing depths at initial placement and at least annually after the initial placement.13

RISK ASSESSMENT

Determining disease risk is an integral part of the assessment phase. No absolute list of risks has been developed. There is some evidence that several physical and medical conditions affect peri-implant disease.10,14,15 Outcomes of the risk assessment will help determine individual supportive care.15 The goal of treatment should be longevity of the implant. Understanding the risks involved with disease progression are integral to that process.

Presence of oral biofilm is a risk factor for peri-implant mucositis. The clinician can contribute to plaque retention if the wrong type of instrument is used on the implant. Surfaces that are scratched will retain plaque easier and the patient will have a difficult time maintaining a plaque-free surface. Metal instruments have a higher risk of scratching the abutment collar surface and should not be used.12 The previous presence of periodontitis also relates to the higher risk of peri-implantitis. Patients who had implants placed for reasons besides tooth loss associated with periodontitis have demonstrated lower incidences of peri-implantitis.15

Peri-implant tissue can either be keratinized or nonkeratinized. Keratinized attached tissue indicates a successful biologic seal. Nonkeratinized unattached tissue does not indicate failure of the dental implant but does put the patient at higher risk of peri-implantitis. Anatomy deficiencies also need to be noted, as they may impede self-care or indicate higher risk of peri-implantitis. These potential deficiencies are vertical and/or horizontal ridge inadequacies, shallow vestibular depths, and less than ideal restorations.9

affiliated with bone loss.PHOTO CREDIT: CHARLES REGALADO, DDS, SPOKANE, WASHINGTON

Iatrogenic complications can adversely affect the dental implant. Most prostheses are cemented onto the implant. Excess subgingival cement has been related to higher infiltrate of inflammatory cells, putting the patient at risk of bone loss. The inflammatory reaction is related to a foreign body reaction (Figure 3).16 Surgical placement can also influence biofilm and calculus removal. If the prostheses is hard to keep clean, there is a higher risk of peri-implant disease.15

Smoking and uncontrolled diabetes are risks for the development of peri-implantitis. Both smoking and uncontrolled diabetes relate to poor healing and will not only affect placement but nonsurgical treatment, as well. There is a 7.3% late failure rate among implants in patients with uncontrolled diabetes. This is most likely related to slow tissue turnover and compromised blood flow.15 Fifty-three percent of smokers have signs of peri-implantitis. Additionally, genetics and alcohol consumption have been implicated in the risk of peri-implantitis.15 Smoking combined with poor self-care has the highest risk factor for peri-implantitis.16 Nutritional counseling and smoking cessation should be included in the care plan.

PROFESSIONAL CARE OF THE IMPLANT

Assessment of the dental implant will determine the nonsurgical treatment choices. Peri-implant mucositis can be treated successfully, while peri-implantitis treated nonsurgically has limited effectiveness.7,9,10,13 At the first sign of inflammation, treatment should be initiated. The main goal of nonsurgical therapy is to eliminate inflammation through the removal of calculus and biofilm.7 Any sign of inflammation should be treated quickly, as the risk of peri-implantitis is great in the presence of inflammation. A treatment plan must be tailored to the individual patient. There is no standardized protocol for nonsurgical treatment of peri-implant disease, yet all assessments should be considered when treatment is initiated.13

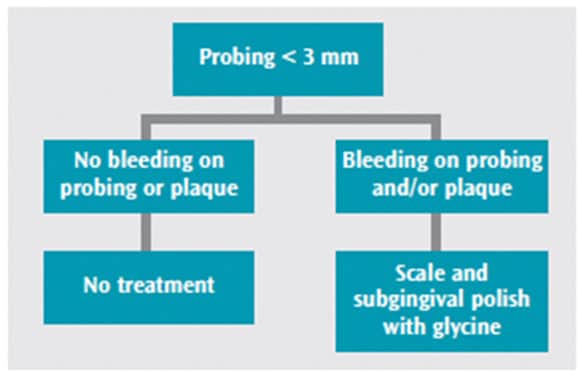

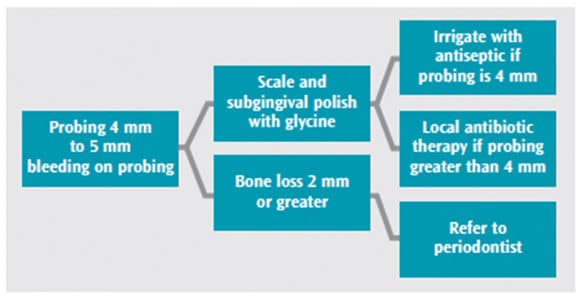

The 4th European Workshop on Periodontology created a consensus on clinical procedures that can help improve implant survival. This workshop’s cumulative interceptive supportive therapy, based on systematic reviews associated with the best outcomes, can be used as a guideline for treatment. The consensus was that mechanical removal of oral biofilm and calculus must be completed to resolve inflammation. Removal should be through subgingival air polishing and scaling. Dependent on probe depths and bleeding on probing, the addition of antimicrobial irrigation or locally applied antibiotics may be beneficial (Figure 4 and Figure 5).11 When bone loss is > 2 mm, a referral to the periodontist is recommended.10

Implant Survival and Complications.10

TREATMENT OF PERI-IMPLANT MUCOSITIS AND PERI-IMPLANTITIS

Nonsurgical treatment of peri-implant disease is a controversial subject with some discrepancies in the literature. Subgingival air polishing is a novel technology that removes biofilm from periodontal pockets. It is safe with root surfaces, soft tissue, and dental implants. Subgingival air polishing uses glycine powder instead of sodium bicarbonate. The glycine powder is gentler on titanium implant surfaces, leaving the surface smooth with no damage. This technology can be used in shallow and deeper pockets. Subgingival air polishing is designed to remove biofilm but does not remove calculus.17 The glycine powder air polisher has demonstrated better outcomes than professional debridement alone.18 De Siena et al18 demonstrated the subgingival air polisher and debridement decreased probing depths and less bleeding over 6 months when compared with debridement only.

Traditionally, plastic curets were used to debride dental implants. Plastic instruments broke easily and were difficult to adapt to the implant and abutment.19 Mann et al20 found that the use of plastic-covered ultrasonic tips left plastic fibers behind that had the potential of increasing the failure rate of the dental implant. Plastic curets are unable to remove residual cement and will break if used to try to remove the cement. To prevent scratches on the implant and abutment, the metal has to be softer or the same hardness as the titanium. The best choice of manual instruments is graphite, gold-platinum alloy, or titanium.20 The use of specialized ultrasonic inserts/tips may be beneficial due to the lavage and mechanical removal of biofilm.9,20

While nonsurgical therapy can be effective on peri-implant mucositis, an adjunct may be needed to reduce inflammation. The use of an antimicrobial irrigant has been shown to reduce bleeding on probing and can enhance the outcome of nonsurgical treatment.11,22 The most common antimicrobial irrigants are 0.12% chlorhexidine and essential oils. A one-time use of an antimicrobial rinse is not beneficial.22 Nonsurgical treatment of peri-implantitis has not been successful. When bone loss occurs, the use of locally applied antibiotics may help arrest further loss.23 A referral to a periodontist to evaluate the extent of loss and the future of the implant is necessary.

MAINTENANCE

Improved outcomes are associated with supportive care every 3 months to 6 months. Supportive care appointments include clinical assessment of the implant, professional removal of biofilm and calculus, and individualized self-care for the implant.3 The implant should be assessed every 3 months in the first year and then adjusted according to patient needs. Preventing peri-implantitis is key. Long-term success is dependent on the health of the supporting peri-implant tissues.10

Due to the design of the prosthesis, it may be difficult for the patient to keep the area clean.7 Before the dental implant is placed, the patient needs to understand there may be unconventional plaque-control methods necessary. Success of the implant is largely dependent on the lack of oral biofilm.21 Schwarz et al23 found—much like gingivitis—the lack of self-care for 21 days increases the risk of peri-implant mucositis. Impeccable oral hygiene at home is the best prevention for peri-implant disease. Risks, including plaque control, should be discussed at every maintenance appointment. Individualized care needs to be planned with the patient so he or she will be more likely to comply with treatment.9 Education on signs of inflammation is important so patients can monitor at home.

The use of a powered toothbrush should be avoided before osseointegration has been completed. Once osseointegration is confirmed, a powered toothbrush is the best option for plaque removal.8 Plaque removal along the gingival margin is key in the reduction of inflammation. This can be challenging due to the design of the prosthesis.7 Other hygiene aids are necessary beyond a toothbrush to reduce plaque. Tufted floss, interproximal brushes without metal wires, rubber tips, and/or end-tufted brushes may be needed. Anti-inflammatory toothpaste can also benefit this patient population.8

CONCLUSION

Dental implants are a successful way of restoring both smile and oral function. Once placed, they are subjected to the same challenges as teeth. Peri-implant disease affects close to half of dental implants and with 500,000 placed annually, dental hygienists will treat many compromised implants.1 The dental hygienist is on the forefront of diagnosis and treatment and, with limited successful treatment options, it is imperative to catch peri-implant disease early.7 Recognition and education on risk factors can help patients understand their role in the dental implant process and maintenance. Early signs of inflammation are important to recognize, as peri-implant mucositis can successfully be treated nonsurgically; once bone loss occurs, treatment becomes less predictable.22 The use of proper instrumentation and adjuncts can reduce the risk of bone loss. Developing a treatment plan with the patient increases the success of the dental implant. The dental hygienist is key to educating the patient on the importance of maintenance, including appropriate self-care.

REFERENCES

- American Academy of Implant Dentistry. Dental Implants Facts and Figures. Available at: aaid.com/about/Press_Room/Dental_Implants_FAQ.html. Accessed August 23, 2018.

- American Academy of Implant Dentistry. About Dental Implants. Available at: aaid.com/about/ Press_Room/History_and_Background.html. Accessed August 23, 2018.

- Heitz‐Mayfield LJA, Salvi GE, Mombelli A, et al. Supportive peri‐implant therapy following anti‐infective surgical peri‐implantitis treatment: 5‐year survival and success. Clin Oral Impl Res. 2018;29:1–6.

- Chai WL, Brook IM, Palmquist A, van Noort R, Moharamzadeh K. The biological seal of the implant–soft tissue interface evaluated in a tissue-engineered oral mucosal model. J Royal Society Interface. 2012;9:3528–3538.

- Araujo M, Lindhe J. Peri-implant health. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S249–S256.

- Berglundh, T, Armitage, G, Araujo MG, et al. Peri-implant diseases and conditions: Consensus report of Workgroup 4 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-implant Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S313–S318.

- American Academy of Periodontology. Peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis: a current understanding of their diagnoses and clinical implications. J Periodontol. 2013;84:436–442.

- Do J. Support long-term success. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2015;13(10):45–50.

- Newman M, Takei H, Klokkevold P, Carranza F. Carranza’s Clinical Periodontology. 12th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier Saunders; 2015.

- Lang N, Berglundh T, Heitz-Mayfield L, Pjetursson B, Salvi G, Sanz M. Consensus statements and recommended clinical procedures regarding implant survival and complications. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2004;19Suppl:150–154.

- Fakhravar B, Khocht A, Jefferies SR, Suzuki JB. Probing and scaling instrumentation on implant abutment surfaces: In vitro study. Implant Dent. 2012;21:311–316.

- Klinge B, Meyle J, Working Group 2. Peri-implant tissue destruction. The Third EAO Consensus Conference 2012. Oral Impl Res. 2012;23(Suppl 6):108–110.

- Renvert S, Polyzois I. Risk Indicators for peri-implant mucositis: a systematic literature review. J Clin Periodontol 2015;42 (Suppl. 16):S172–S186.

- Lindhe J, Meyle J. Peri-implant diseases: Consensus Report of the Sixth European Workshop on Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35(Suppl. 8):282–285.

- Marcantonio C, Nicoli LG, Junior EM, Zandim-Barcelso DL. Prevalence and possible risk factors of peri-implantitis: a concept review. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2015;16:750–757.

- Tatullo M, Marrelli M, Mastrangelo F, Gherlone E. Bone inflammation, bone infection and dental implants failure: histological and cytological aspects related to cement excess. J Bone Jt Infect. 2017; 17;2:84–89.

- Daubert D. Subgingival air polishing. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2013;11(12):69–73.

- De Siena F, Corbella S, Taschieri S, Del Fabbro M, Francetti L. Adjunctive glycine powder air-polishing for the treatment of peri-implant mucositis: an observational clinical trial. Int J Dent Hyg. 2015; 13:170–176.

- Armitage G, Xenoudi P. Post-treatment supportive care for the natural dentition and dental implants. J Periodontol. 2016:71:164–184.

- Mann M, Parmar D, Walmsleu AD, Lea SC. Effect of plastic-covered ultrasonic scalers on titianium implant surfaces. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012:23:76–82.

- Renvert S, Roos-Jansaker A, Claffey N. Non-surgical treatment of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis: a literature review. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:305–315.

- Romanos G, Javed F, Degado-Ruiz R, Calvo-Guirado J. Peri-implant diseases: a review of treatment interventions. Dent Clin N Am. 201559:157–178.

- Schwarz F, Becker K, Sager M. Efficacy of professionally administered plaque removal with or without adjunctive measures for the treatment of peri-implant mucositis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42(Suppl 16):S172–S186.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2018;16(9):28–31.