PonyWang / E+ / getty images plus

PonyWang / E+ / getty images plus

The Ethics of Infection Control

Dental hygienists must be prepared to address breaches in infection control to ensure the safety of patients and dental team members.

Compliance with infection control standards is an ethical obligation and is key to providing quality care in the practice of dentistry. While ethics is a broad term for a set of moral principles,1 it helps guide the decisions oral health professionals make during patient care. Infection control has always been at the forefront of delivering safe and effective dental care; however, COVID-19 has heightened the awareness of both practitioners and patients regarding infection control compliance. The global pandemic has challenged the profession to find even more stringent ways dental care can safely be delivered, resulting in significant changes to infection control protocols. Given that COVID-19 is likely to persist in some capacity rather than be completely eradicated,2 in addition to the presence of other viral threats—such as monkeypox and hepatitis B—the intense focus on infection control in dental and medical settings is likely to remain.

Adhering to infection control standards is of the utmost importance, yet dental hygienists may find themselves in practices where breaches in infection control exist. These breaches can vary from subtle to egregious. The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) “Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Setting—2003” established acceptable standards of practice for the dental profession.3 This document provides the guidance needed to deliver safe dental care to patients and ensure a safe environment for workers.

State dental boards have also adopted rules and regulations regarding infection control protocols and standards that must be followed. Table 1 lists some of the most common breaches in infection control protocols.4

![TABLE 1. Common Breaches in Infection Control Protocols]() Re-using Face Masks

Re-using Face Masks

An example of a breach in infection control protocol is re-using face masks between patients instead of donning a new mask after the treatment of each patient. According to the CDC, “Dental health care personnel should wear a surgical mask that covers both their nose and mouth during procedures that are likely to generate splashes or sprays of blood or body fluids and while manually cleaning instruments. Surgical facemasks are cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as medical devices. FDA notes that surgical masks are not intended to be used more than once.”5,6 Therefore, face masks should be changed between patients or during patient treatment if they become wet.

Toomey et al,7 describes the only exception: “The extended use and reuse of single-use surgical masks and respirators (with or without reprocessing) should only be considered in situations of extremely critical shortage.” Hence, re-using face masks in the absence of a supply shortage is unacceptable and considered a breach in infection control.

Sterilizing Handpieces

Another example of an infection control breach is not sterilizing handpieces after each use. CDC guidelines for infection prevention and control state: “Between patients, dental healthcare personnel should clean and heat-sterilize handpieces and other intraoral instruments that can be removed from the air and waterlines of dental units”8 In 2015, the FDA updated this guidance based on a compilation of landmark studies that determined the internal components of handpieces can become contaminated, which—if not sterilized—could cause cross-contamination.9–11 Dental practitioners may not be aware of this updated guidance.

Upholding the Oath

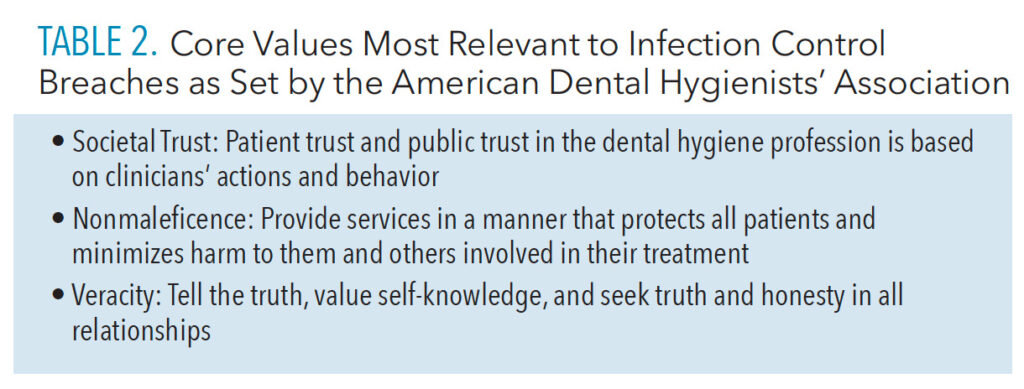

Infection control breaches not only violate dental practice acts, but, on another level, they violate the Dental Hygiene Oath, which requires that dental hygienists uphold the “…highest standards of professional competence and personal conduct in the interest of the dental hygiene profession and the public it serves.”12 Infection control breaches also violate the American Dental Hygienists’ Association’s Code of Ethics.13 Table 2 demonstrates the most relevant core values to this issue. These values serve as the foundation of professional ethical conduct and guide dental practitioners to ensure safe delivery of care within their scope of practice.

Addressing Breaches in Infection Control

When breaches in infection control occur, several strategies can be used to address the situation—ranging from voluntarily terminating employment to filing a complaint with the state dental board or Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA).14 A dental hygienist may immediately decide that an environment where infection control breaches continually occur is not the right practice for him/her. If a dental hygienist decides to discuss the breaches prior to deciding on whether to terminate employment, he or she needs to address the situation in a polite, nonconfrontational, and professional manner with those involved in the breach. If a particular co-worker or dentist employer consistently practices substandard infection control, the discussion should begin with him or her. By bringing the breach to the attention of the violator and sharing the ramifications of infection control violations, the dental hygienist may help him or her understand that a breach exists and the repercussions of this behavior. Additionally, if the conversation is initiated with safety as the top priority, the violator may be more willing to listen to the concerns. All dental team members must understand the importance of infection control practices to keep patients and employees safe.

When discussing infection control breaches, all infractions should be presented in writing accompanied by copies of the CDC’s “Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Setting—2003,” OSHA Standards for Dental Practices, and the state dental practice act. Each violation should include notice of the corresponding recommendation or standard. Infection control protocols often change, and breaches may be occurring due to ignorance of the recommendations and standards. Co-workers and employers may even appreciate being informed as continuation of the breaches could be a legal liability.

What if, after addressing infection control breaches, nothing changes? If the infection control breach involves a co-worker, then it is time to bring this to the attention of the dentist employer. If the employer is unaware of the problem, he or she will not be able to address the situation and correct the action of the employee. Employers should know their responsibilities under OSHA and state dental practice acts and address any breaches immediately so as to avoid complaints to these organizations.

After bringing infection control breaches to the attention of the employer, what if he or she is dismissive of the presented concerns? Then difficult decisions need to be made. The dental hygienist needs to remember that all oral health professionals have the ethical responsibility, obligation, and moral duty to ensure they stay current with infection control protocols required to prevent the transmission of infectious diseases and understand why they are necessary. As such, it may be necessary to file a complaint with OSHA (osha.gov/workers/file_complaint.html)14 and/or the appropriate state dental board. Some states allow employees to file a complaint anonymously, without fear of retribution.

If reporting infection control breaches is the necessary path, it may be time to seek employment at an office that upholds the standards for infection control in dental offices. When interviewing for a new position, it is prudent to ask questions about the office’s infection control protocols, request to see written policies, and even observe the office prior to accepting employment.

Summary

Increasingly attention has focused on proper infection control protocols and their implications for the safety of oral health professionals and patients. Proper infection control is essential in dental practices to prevent the spread of infectious diseases such as COVID-19, influenza, hepatitis, and other emerging diseases. When attention is focused on the ramifications of infection control breaches, dental hygienists should examine not only the legal implications but the ethical implications as well. It is the ethical duty of dental hygienists to ensure proper infection control protocols are followed and to re-affirm the public’s trust in the profession.

References

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Ethics. Available at: merriam-webster.c/m/dictionary/ethic. Accessed September 13, 2022.

- Locklear M. For COVID-19, endemic stage could be two years away. Available at: news.yale.edu/떖/葓/葑/covid-19-endemic-stage-could-be-two-years-away. Accessed September 13, 2022.

- Kohn WG, Collins AS, Cleveland JL, et al. Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings—2003. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(RR-17):1–61.

- Nock K. 6 Common Infection Control Breaches in Dental Practices. Available at: dentalproductsreport.com/view/䁴-common-infection-control-breaches-in-dental-practices Accessed September 13, 2022.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Personal Protective Equipment. Available at: cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/faqs/personal-protective-equipment.html. Accessed September 13, 2022.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. N95 Respirators, Surgical Masks, Face Masks, and Barrier Face Coverings Available at: fda.gov/medical-devices/personal-protective-equipment-infection-control/n95-respirators-surgical-masks-face-masks-and-barrier-face-coverings. Accessed September 13, 2022.

- Toomey EC, Conway Y, Burton C, et al. Extended use or reuse of single-use surgical masks and filtering face-piece respirators during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: a rapid systematic review. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2021;42:75–83.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dental Handpieces and Other Devices Attached to Air and Waterlines. Available at: cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/faqs/dental-handpieces.html. Accessed September 13, 2022.

- Chin JR, Miller CH, Palenik CJ. Internal contamination of air-driven low-speed handpieces and attached prophy anglesJ J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:1275–1280.

- Chin JR, Westerman AE, Palenik CJ, Eckert SG. Contamination of handpieces during pulpotomy therapy on primary teeth. Pediatr Dent. 2009;31:71–75.

- Herd S, Chin J, Palenik CJ, Ofner S. The in vivo contamination of air-driven low-speed handpieces with prophylaxis angles. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:1360–1365.

- Beemsterboer P. Ethics and Law in Dental Hygiene. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2017.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Code of Ethics. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/AD_A_Code_of_Ethics.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2022.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Workers’ Rights. Available at: osha.gov/Publications/osha3021.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2022.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. October 2022; 20(10)14-16.