PHONIX_A/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

PHONIX_A/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Joining the Emergency Preparedness Team

Oral health professionals have unique skills that can be invaluable to emergency preparedness teams.

This course was published in the June 2018 issue and expires June 30, 2021. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the role of the dental identification team in emergency preparedness.

- Identify the appropriate education and equipment needed in preparing for a disaster.

- Discuss strategies for preparing the dental practice for emergencies.

- List the specific skills held by oral health professionals that can be helpful in emergency management.

In addition to investigators, dental identification (ID) teams can include forensic pathologists, anthropologists, medical examiners, and forensic odontologists. The American Board of Forensic Odontology supports the use of dental hygienists as members of mass fatality victim dental identification (DVI) teams, and dental hygienists have served on victim ID teams in previous disasters.5 These teams are managed by a forensic odontologist (dentist) who can designate dental volunteers to subsections of dental teams including: identification of a dental registrar, post-mortem (PM) and antemortem (AM) dental record teams, dental radiographers, and records reconciliation teams.4–8 Research by Bradshaw et al9 reported 86% of US dental hygienists surveyed in 2016 had an interest in disaster preparedness training and response.

Applicable to both preparedness (documentation of living records) and response (using living records and forensic odontology), the most reliable, scientifically proven, and legally substantiated methods of identification are through biometric data. Biometrics refers to quantifiable or measurable data related to human characteristics and traits. Biometric identification includes using comparisons of tissue or DNA samples, models, fingerprints, and other physical or anatomical identification data.10 Often referred to as primary identifiers, biometrics include the observation and documentation of teeth and oral anatomy; skin friction ridge analysis of the fingers, palms, and sole prints; and DNA to assign an identity to human remains.10 The type of identification method(s) used depends on the circumstances of the disaster and resources available. Forensic dental identification is beneficial in cases where high impact, speed, and/or combustion results in burned, fragmented, and/or co-mingling of skeletal remains, and in the absence of normal means of personal identification items.11

Tooth enamel is the hardest surface in the body and can withstand decomposition and heat better than most other anatomy. The unique anatomical variations and restorative treatment provide data for use by forensic odontologists to confirm identity.6,12 A recent study by Xavier,13 found that DNA extraction from stored primary teeth could also be used as an alternative self-sample in AM records for DVI. In some cases, particularly with rigor mortis, it is necessary to surgically resect the victim’s jaws to access tooth structures. This may allow for ease in production of proper records and radiographs.6,12

EXPERIENCE AND TRAINING

Dental hygienists are experienced in infection control procedures, medicolegal documentation, dental surgical assistance, public health, exposing and interpreting radiographs, and serving in both administrative and management roles. Dental hygienists also maintain regular cardiopulmonary resuscitation and basic life support training. Dental hygiene curriculum includes dental anatomy, oral pathology, microbiology, pharmacology, public health, research methodology, practice management, and ethics; however, more training is needed to prepare dental hygienists to serve in disaster preparedness. DVI is technically challenging and environmentally difficult. More training is needed to prepare dental hygienists for biohazards associated with natural and man-made disasters, as well as for working in temporary morgue settings.14–16 Forensic dentistry is a vital contributor to the identification of victims in mass fatality incidents (MFIs); however, each MFI and management of victim identification is unique. Forensic odontologists and dental hygienists not only require education in their professional area of expertise—they also need training to facilitate their safe and effective work with DVI teams and in the environments in which they are operating. Dental hygienists who volunteer for MFIs may need to live and work in environments where occupational and environmental risks are high.14–16 Deployment to help with recovery efforts during a MFI requires all responders to have individual and collective training designed to reduce the occupational and environmental threats.14–16 Although forensic odontologists and dental hygienists have contributed to identification of victims in MFIs, there is a limited number of trained dental professionals to assist in DVI. The use of untrained volunteers can be problematic in terms of the skill sets and experience required.1,6,7,17 Lessons learned from previous MFIs identified issues with accuracy and completeness of records entered during actual disaster events. However, established recovery efforts may be able to provide in-time training.

EQUIPMENT

Dental hygienists can support the preparedness of disaster ID teams by helping to maintain equipment and response kits. The equipment used by dental ID teams is similar to what is used in routine clinical care; however, several major differences exist in infection control and radiation safety standards.6,7 Response kits should be maintained and include a lead apron, X-ray image receptor holders, portable X-ray devices with press-and-seal wrap barriers, personal dosimeter badges, surgical gown with full sleeves, surgical cap, protective eye goggles, the appropriate mask, shoe covers, surgical caps, and utility wax.18

Utility wax can be used to create a seal between the teeth and image receptor-holding device in the absence of occlusion. In special circumstances, additional protection may be needed. During jaw resections, all involved in the procedure should wear a respiratory mask. When victims have been involved in any incident leading to possible bone shards or sharp projectiles in the mouth, cut-resistant gloves may be required.18 In some situations, such as terrorist incidents, where there is a threat of hazardous material or significant chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear risk, dental hygienists may be debriefed in additional protocol to follow in a real-time event. Some equipment or offices used for temporary mortuary settings may be unacceptable for returned routine clinical use.

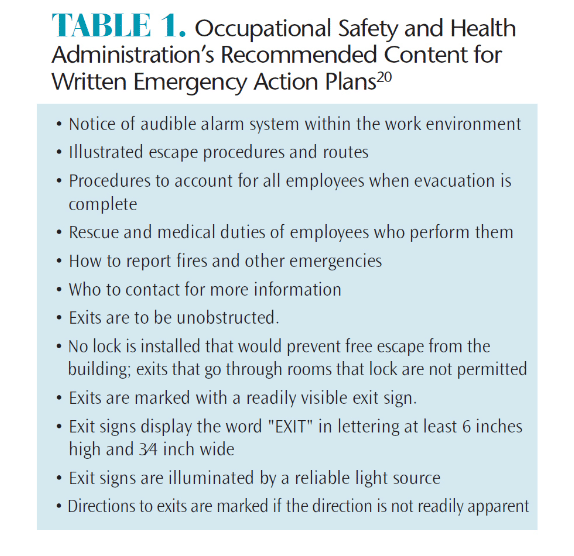

PREPARING THE PRACTICE

Dental hygienists who own their practices, are directors of clinics, or who help manage dental practices also need to safeguard their facilities, staff, and patients in the event of a disaster. Emergency preparedness protocol should consider a wide range of possible scenarios to include mudslides, earthquakes, fires, hurricanes, avalanches, floods, and tornadoes or man-made incidents involving transportation accidents, bioterrorism, power and structural failures, detonated bombs, chemical spills, radiation leaks, and active shooter situations.19 The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requires businesses with 11 or more employees to have a written emergency action plan.20 Emergency plans should include basic office emergency protocol, evacuation and escape routes and specified emergency alert equipment (Table 1).20 Several recommendations are specified for retrieving dental records after water damage. As dental records may be given over to authorities for DVI efforts, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention21 has made the following water safety and recovery recommendations:

- Do not revisit areas with raised water levels until authorities announce that it is safe to return. Downed power lines, structural damage, and poisonous snakes and other dangerous animals are some of the leading causes of mortality and morbidity rates when rising water levels are an issue.

- Boil-water advisories caution against the use of public water systems for the delivery of patient care through the dental unit, ultrasonic scaler, or other dental equipment. Patient care should not resume until the boil-water advisory is canceled. After the advisory is cancelled, incoming public water system water lines in the dental office should be flushed by turning all faucets on for at least 30 minutes, including water lines to dental equipment that uses the public water system. Dental unit water lines should be disinfected.

- When recovering wet dental records from a flood or fire, oral health professionals should use gloves. If necessary, boots and goggles or safety glasses for eye protection should be worn. There may be infectious organisms in floodwater.

- Soaked paper records begin to deteriorate within 3 hours and may completely dissolve in 4 days to 5 days. Important water-damaged paper records can be frozen and freeze- or vacuum-dried within the first 10 hours. Freeze-drying materials converts the frozen water to a gas and by-passes the liquid state altogether.

SPECIFIC RESPONSE ROLES

Dental hygienists can assist police, coroners, and medical examiners to find AM records to include collecting dental casts, fixed and removable dentures, orthodontic appliances, or photos taken for cosmetic work. Reconciliation teams enter AM and PM records into a computer database to search best matches. Participating in PM dental examinations to chart dental traits and conditions and exposing and organizing dental radiographs and intraoral photos can also be performed by dental hygienists.

A multiverification approach is used during PM examinations and reconciliation to ensure accuracy. Typically three team members are involved—two forensic odontologists and a dental hygienist. In rotating order, one team member examines the teeth and calls out the findings to a second team member who records those findings. The third team member is an observer who makes sure each finding is called out and recorded correctly. This type of data collection is repeated after each multiverification team member has completed one of the three roles (examiner, recorder, and observer).6,7,22 Dental hygienists also provide support by monitoring other team members for emotional and psychological fatigue.7 The devastating effects following a MFI can be intensified or exaggerated when the absolute identification of deceased persons is needed for the family and community at large for legal reasons and to reduce public health risks.22–24 Cultural practices regarding burial and grieving and important legal processes following a death cannot be settled until a formal identification of the deceased has been completed. Long delays in identification can cause feelings of anger and distrust, adding to the emotional hardship experienced by families.22–24 Dental hygienists increase the capacity and efficiency of work that can be completed, solidifying the increased need for their participation in MFI.

Dental hygienists are eligible for membership in the American Society of Forensic Odontology, which offers regular case studies and continuing education courses on victim identification. Dental hygienists can also serve as members of their local division of the civilian volunteer group, Medical Reserve Corps (MRC). The MRC is a national network of local volunteer units that organize and utilize medical and public health professionals, such as physicians, nurses, pharmacists, dentists, dental hygienists, and epidemiologists, who want to prepare for and respond to emergencies. The MRC provides consistent emergency preparedness and response training exercises and course work for its members.

SAFETY

OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY HIRSCHFELD SCHOOL OF DENTAL HYGIENE

To optimize the efficiency and effectiveness of response capabilities, each member of the dental ID team should possess the necessary skills (and preferably experience) in the necessary equipment, software, and biosafety standards when working in a temporary mortuary setting. The collection, interpretation, recording, and comparing of AM and PM dental records is time consuming and complicated.

Several sophisticated computer software applications are available for organizing and comparing the large amounts of dental information.25,26These systems can sort large numbers of AM records to reduce the number of potential matches of PM records. AM and PM dental records must be linked to the specific mass fatality incident.27

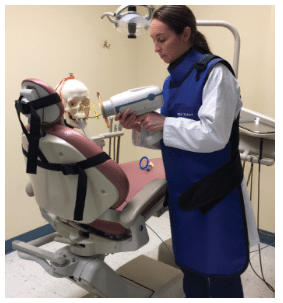

Portable, hand-held X-ray equipment is ideal for use in DVI efforts; however, dental hygienists must be knowledgeable in the safe use of the equipment, as the operator must hold the device during the exposure. Handheld X-ray devices are compatible with digital imaging and equipped with a backscatter ring shield to protect the operator from scatter radiation when held with the unit parallel to the floor at the mid-torso level. However, this position can be difficult to maintain when imaging human remains that are broken and fragile. In addition, dental hygienists must stand behind the portable X-ray unit when aligning the position indication device (PID) to the image receptor to achieve full protection from the backscatter ring shield.

External aiming rings of image receptor holding devices can assist the dental hygienist in maintaining the handheld unit at mid-torso level to determine the precise angulations needed for optimal images using the paralleling technique.28 The operator can wear a wrap lead apron to protect from scatter radiation. Wrap lead aprons allow radiographers to be hands-free when using portable X-ray equipment (Figure 1).

Image receptor-holding devices may need modifications to work with handheld devices and human dental remains due to lack of occlusion and equipment interference with the proper alignment of image receptors.29 The backscatter ring shield will block a standard image receptor holding device from being close to the open-ended PID and can cause an error in cone cut without modifications. Multimedia lectures on simulated dental remains allow dental hygienists to become comfortable with PM X-ray exposures.

CONCLUSION

Oral professionals need to educate their local emergency response agencies about their unique skills. Dental hygienists can create emergency plans to protect their office and patients. Further training and education of oral health professionals is needed in order for dental hygienists to fully integrate into emergency preparedness.30–33 Dental hygienists working in forensics and disaster preparedness have been recognized for their community service and contributing skills in victim identification—still additional publications/curriculum detailing emergency response experiences from the dental hygiene perspective are needed.

While volunteerism is valued and necessary, prior training can help ensure responders are skilled enough to make timely and accurate identifications. Taking a continuing education course is not enough. Oral health professionals should consider joining a forensics society or in an emergency and response preparedness organization to become part of a deployable, multidisciplinary response team.

REFERENCES

- Nuzzolese E, Lepore MM, Cukovic-Bagic I, Montagna F, Di Vella G. Forensic sciences and forensic odontology: issues for dental hygienists and therapists. Int Dent J. 2008;58:342–348.

- United States Department of Homeland Security Federal Emergency Management Agency. Emergency Preparedness Materials. Available at: fema.gov/media-library/resourcesdocuments/ collections/344. Accessed May 28, 2018.

- Lindsay B. Federal Emergency Management: A Brief Introduction. Available at: fas.org/sgp/crs/homesec/R42845.pdf. Accessed May 28, 2018.

- Teahen P. Mass Fatalities: Managing the Community Response. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press; 2012: 1–3.

- American Board of Forensic Odontology Inc. American Board of Forensic Odontology Diplomats Reference Manual. Available at: abfo.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/ABFO-Reference-Manual-1-22-2013-revision.pdf. Accessed May 28, 2018.

- Ferguson D, Sweet D, Craig B. Forensic dentistry and dental hygiene: how can the dental hygienist contribute? Canadian Journal of Dental Hygiene. 2008;42(4):203–211.

- Brannon RB, Connick CM. The role of the dental hygienist in mass disasters. J Forensic Sci. 2000;45:381–383.

- Newcomb TL, Bruhn AM, Giles B. Mass fatality incidents and the role of the dental hygienist: are we prepared? J Dent Hyg. 2015;89:143–151.

- Bradshaw B, Bruhn AP, Newcomb TL, Giles B, Simms K. Disaster preparedness and response: a survey of US dental hygienists. J Dent Hyg. 2016; 90:313–322.

- Micheli-Tzanakou E, Plataniotis K. Biometrics: Terms and Definitions. New York: Springer. 2011;142-147.

- Kieser J, Laing W, Herbison P. Lessons Learned from the large-scale comparative dental analysis following the South Asian tsunami of 2004. J Forensic Sci. 2006;51:109–112.

- Lake AW, James H Berketa JW. Forensic odontology involvement in fatality victim identification. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2012;8:148–156.

- Xavier M, Bento A, Costa A, et al. Primary teeth as DNA reference sample in disaster victim identification (DVI). Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2001;3:381–382.

- Hardin NJ. Infection control at autopsy: a guide for pathologists and autopsy personnel. Curr Diagn Pathol. 2000;6:75–83.

- Burton JL. Health and safety at necropsy. J Clin Path. 2003;56:254–260.

- Sharma BR, Reader MD. Autopsy room: a potential source of infection at work place in developing countries. Am J Infect Dis. 2005;1:25–33.

- Wetli C. Autopsy safety. Lab Med. 2001;8:451–453.

- Danforth R, Herschaft EE, Leonowich JA. Operator exposure to scatter radiation from a portable hand-held dental radiation emitting device while making 915 intraoral dental radiographs. J Forensic Sci. 2009;54:415–421.

- Collins D. Emergency Planning and Disaster Recovery in the Dental Office. Available at: ada.org/~/media/ADA/Member%20Center/FIles/ada_disaster_manual.ashx. Accessed May 28, 2018.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Emergency Action Plans. Available at: osha.gov/pls/ oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_id=9726&p_table=standards. Accessed May 28, 2018.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Food, Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Information for Use Before and After a Disaster or Emergency. Available at: cdc.gov/disasters/ foodwater/index.html. Accessed May 28, 2018.

- Vale GL, Noguci TT. The role of the forensic dentist in mass disasters. Dent Clin North Am. 1977; 21:123–135.

- McCarroll JE, Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ, Hermsen JM. Posttraumatic stress symptoms following forensic dental identification: Mt. Carmel, Waco, Texas. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:778–782.

- Morgan OW, Sribanditmongkol P, Perera C, Sulasmi Y, Van Alphen D, Sondorp E. Mass fatality management following the South Asian tsunami disaster: case studies in Thailand, Indonesia, and Sri Lanka. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e195.

- Zohn HK, Dashkow S, Aschheim KW, et al. The odontology victim identification skill assessment system. J Forensic Sci. 2010;55:788–791.

- James H. Thai tsunami victim identification overview to date. J Forensic Odontostomatol. 2005;23:1–18.

- Clement JG, Winship V, Ceddia J, Al-Amad S, Morales A, Hill AJ. New software for computer-assisted dental-data matching in disaster victim identification and long-term missing persons investigations: “DAVID Web.” Forensic Sci Int. 2006;159(Suppl 1):S24–29.

- Bruhn AM, Newcomb TL, Giles B. Evaluating imaging techniques for intraoral forensic radiography with the dental hygienist as part of the forensic radiology team. J Forensic Ident. 2016;66:22–36.

- Newcomb TL, Bruhn AM, Giles B, Garcia HM, Diawara N. Testing a novel 3D printed radiographic imaging device for use in forensic odontology. J Forensic Sci. 2017;62: 223-228.

- Hoffman B. Rethinking terrorism and counterterrorism since 9/11. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. 2002;25(5):303–316.

- Glotzer D, More F, Phelan J, et al. Introducing a senior course on catastrophe preparedness into the dental school curriculum. J Dent Educ. 2006;70:225–230.

- Hermsen KP, Johnson JD. A model for forensic dental education in the predoctoral dental school curriculum. J Dent Educ.2012; 76:553–561.

- Stoeckel DC, Merkley PJ, McGivney J. Forensic dental training in the dental school curriculum. J Forensic Sci. 2007;52:684–686.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. June 2018;16(6):26-29.