Improving Compliance

Oral health professionals can help noncompliant patients improve their dental health by using the interdisciplinary system of behavioral modification.

This course was published in the October 2013 issue and expires 10/31/16. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define the interdisciplinary system of behavioral modification (ISBM).

- Identify contributing factors to patient compliance.

- Discuss the importance of the periodontal program in motivating patients.

- Explain the role of the different components of the ISBM: episodic buffer, phonological loop, and visuospatial sketchpad.

INTRODUCTION

When I have the opportunity to talk with practicing dental hygienists, I often ask what the most significant frustration is that they face in their professional lives. Almost without exception, the answer is, “dealing with noncompliant patients.” It doesn’t seem to matter what type of practice the care is provided in, the problem with noncompliance is universal.

This article,”Improving Compliance,” provides a very useful background to help clinicians consider noncompliant patients from a different perspective. How can we get through to patients? How can we make patients realize they have a disease with serious health consequences, and that following our maintenance and self-care recommendations will help? Of course, the answers are not simple and require the commitment of the entire dental team, but dental hygienists are the ideal candidates to lead this process of education and communication.

In collaboration with the American Academy of Periodontology, the Colgate-Palmolive Company is delighted to have provided an unrestricted educational grant to support the fourth article of this educational series on using a team approach to improve periodontal outcomes. I hope you find this article a valuable resource to help improve compliance among patients in your practice.

—Barbara Shearer, BDS, MDS, PhD

Director of Scientific Affairs

Colgate Oral Pharmaceuticals

Many dental practices have experienced prospective patients who present with significant oral health problems and admit to seeking professional dental care only sporadically. Once a treatment plan is presented, these patients frequently request to schedule the therapy for a later time—never to be heard from again. Likewise, the chances of long-term patients, who have been inconsistent with their oral hygiene maintenance, changing their behaviors are slim. These examples beg the question—is it the responsibility of clinicians to motivate patients to change their behaviors, or should dental hygienists simply accept their noncompliant attitudes?

Evidence suggests that effective self-care and consistent maintenance are integral to helping patients save their teeth. A cohort study by Hujoel et al1 found that one or more maintenance procedures performed successively over a 3-year period reduced tooth mortality by 58%, compared to no maintenance at all. And the more maintenance therapies that were performed, the more significant the decrease in tooth loss.1

Surgical therapy further reduces tooth mortality, but it is not as effective as routine maintenance care.2–4 Untreated patients experience a threefold increase in tooth loss compared to surgically-treated and maintained patients. Without maintenance, surgically-treated patients have twice the rate of tooth mortality. 2–4 Despite these statistics, patients remain unmotivated to change their behaviors—necessitating personalized dental appointments. During the appointment, clinicians should encourage patients to acknowledge their disease in an effort to foster improvement of their oral health. Even then, oral health professionals can expect just 16% of patients to be compliant vs 34% who will not.5

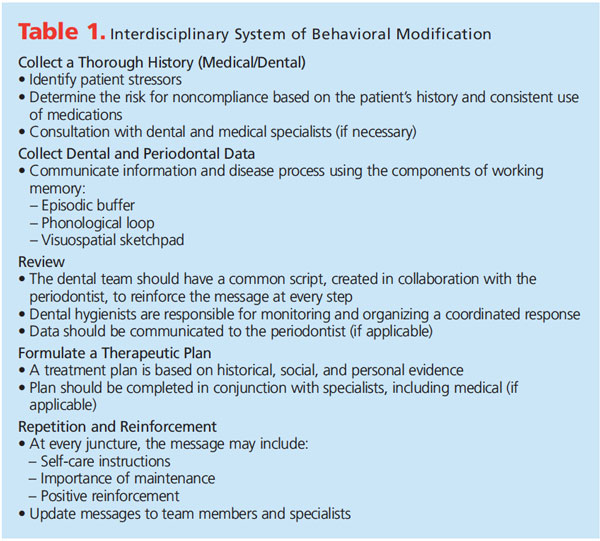

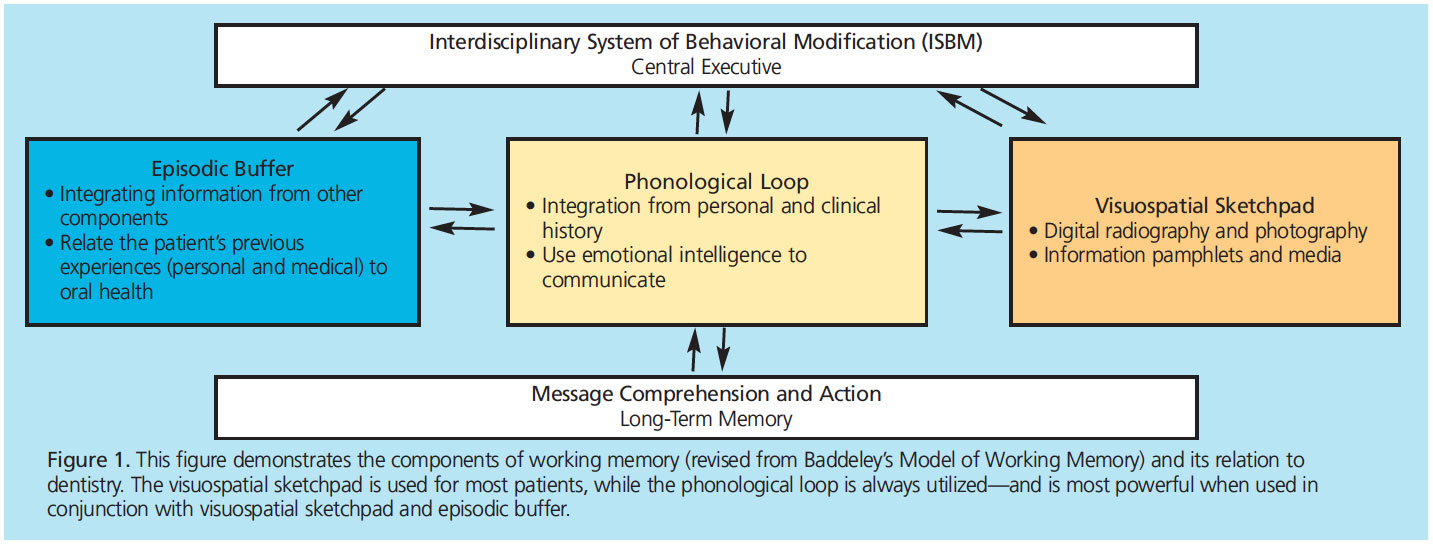

Getting patients to comply with treatment recommendations is a multifaceted process that must be rehearsed and communicated by all team members and the referral network. Creating an interdisciplinary system of behavioral modification (ISBM) involves open communication and conception of a universal message (Table 1). The system is a dental elaboration of Baddeley’s Model of Working Memory6 and the Health Belief Model,7 and involves three factors—episodic buffer, phonological loop, and visuospatial sketchpad—that work together to improve message comprehension and action. The episodic buffer links different types of information to form integrated units; the phonological loop addresses auditory communication; and the visuospatial sketchpad focuses on visual communication (Figure 1).

Much like the dental practice adheres to a “mission statement” as the gold standard for delivering care, the ISBM requires dental professionals to collaborate with a common goal in mind for each patient. When using this approach, changes in a patient’s social, economic, or medical status must be communicated through a debriefing, so all team members can help determine how these changes may impact treatment. An update must also be communicated to the periodontist and his or her clinical team.

MOTIVATION

Noncompliance among patients has been linked to many factors, including age, gender, fear, socioeconomic status, and even turnover in the dental practice.8 The Health Belief Model, however, asserts that three factors positively influence patient compliance:7

- The patient believes he or she is susceptible to thedisease.9

- The patient believes the disease could pose severe consequencesto his or her health.10

- The patient believes the treatment will be beneficial.11

From a dental perspective, periodontal diseases are often asymptomatic, much like diabetes or hypertension. It is challenging to convince patients of their existence unless the dentition is mobile or the periodontium is painful and bleeding. Often, clinicians must remind patients that the health of their mouth directly relates to the health of their body. The oral-systemic link must be explained, with emphasis placed on the fact that oral disease poses risks to overall health. After reviewing their medical history, it is the responsibility of dental professionals to inform their patients about the association between periodontal diseases and their systemic health.

Oral health professionals are also responsible for educating physicians. When the number of individuals receiving health care benefits increases under the Affordable Care Act, more people will have access to primary physician care. It is essential to bring oral health to the attention of primary care physicians. If a physician is concerned about a patient’s oral health and refers the patient to a dentist, the patient is more likely to comply.

Noncompliant patients tend to have more stressors in their lives,12 the probabilities of which must be investigated in order to better understand each patient. This starts with the medical and dental interview, in which the patient’s dental history should be noted and the first incident of noncompliance determined. Clinicians should evaluate the patient’s dental and medical records to determine if noncompliance is the result of a recent traumatic event or prior negative experience in a dental setting. A thorough dental history can help identify the origin of the patient’s dental phobia. Reviewing the patient’s medical history can also reveal historical compliance and health stressors.

In patients with serious health problems, it may be prudent to obtain a medical consultation, even if only to make the patient’s physician aware of dental issues that must be addressed. Treatment plans may need to be adjusted in consideration of the patient’s medical status. For patients who have contraindications to invasive procedures, for example, a tighter maintenance schedule may be preferred over scaling and root planing or surgery.

Patients who do not regularly take their daily medication are likely to be noncompliant. For instance, a patient who does not take his or her prescribed angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker and presents with extreme hypertension is likely to be noncompliant with dental treatment.

Untreated psychological issues, such as depression and bipolar disorder, impact the ability to motivate patients and patients’ ability to make behavioral changes. With the patient’s permission, it can be advantageous for oral health professionals to correspond with the patient’s psychiatrist to understand the stressors in his or her life. Also, patients with low emotional intelligence (the ability to identify and control one’s emotions, as well as the emotions of others) tend to be less compliant.13

THE PERIODONTAL PROGRAM

It is easy for patients to deny having a hidden disease. Through investigation, dental hygienists can identify individual barriers to compliance—but, once revealed, it is up to clinician to make every effort to change patients’ noncompliant behaviors. Dental hygienists’ emotional intelligence aids in communication with patients and other team members, and may help to improve patient compliance. This process, however, is not the sole job of dental hygienists. Rather, the challenge is for all team members to share a common positive message that motivates patients into compliance.

Much in the way that the mouth is thought of as the window to the body, the periodontal program is the window to the dental practice. This program is essential to patients’ overall perception of the practice, and it is the life-blood of a general dental practice. A periodontist’s goal is to release the patient back to the general dentist. Trust between the general dentist and specialist must be established and communication between the practices fluidly exchanged. For instance, the periodontist must trust that the general dentist will know when to refer the patient back for specialty care.

Periodontists determine the most effective ways to treat and prevent periodontal diseases, and they serve as valuable resources for both patients and general practitioners. Knowledgeable about infection, medical issues, and the stressors that contribute to periodontal diseases, periodontists are able to integrate collected patient data to help decide on the best method to motivate patients. In the periodontist’s office, the dental hygiene program is a “boot-camp” extension of the general practitioner’s office. Periodontists understand that once patients are periodontally stable, they should be released back to general practice for comprehensive dental care. Generally, stability is defined as the absence of bleeding on probing with no increase in moderate pocket depths. Bleeding on probing scores and probing results that are consistent increase the likelihood of stable attachment levels.14

Dental hygienists should direct the morning huddle in the practice, as they spend the most time with patients on a daily basis. Through collaboration with the general dentist and specialist, dental hygienists should communicate the patient’s periodontal progress, review pending treatment, and note any changes in maintenance therapy.

The team needs to create a common message that resonates with every clinician and every patient—stressing the importance of repetition and positive reinforcement. Miller’s Law explains that people can hold five items to nine items in their short-term memory15 and remember 1.5 seconds of sound.16 In addition, people can retain approximately 8% to 12% of what they hear.17 If a patient receives a verbal explanation of his or her dental condition one time, the ability of the short-term memory that remembers brief phrases through repetition, or the phonological loop, is limited.18 Repetition of the explanation, in addition to including other types of education, such as spatial and visual communication, allows the information to be connected inside the patient’s episodic buffer.6 When processed in this order, patients can use their working memory to manage action points and transfer important information to their long-term memory.

For example, the team needs to know when a patient reports that he or she has recently quit smoking and the plaque score has decreased. The front office should congratulate the patient and the dentist needs to reinforce the inspirational message. This kind of repetition sends a coherent, common message. It also creates a positive culture in the practice and bonds the team as a caring organization. If only one method of communication, such as verbal, is used, Miller’s Law states patients may need to hear the message seven times for it to resonate. In these cases, verbal repetition is absolutely mandatory to reinforce a message. If multiple levels of communication are used, the ISBM approach explains that the different components of working memory will be more effective than a single level (Figure 1).

EPISODIC BUFFER

The episodic buffer is the most recent addition to the system, and it serves as a storehouse that collects and combines information from the phonological loop and the visuospatial sketchpad. It connects data from the other parts of the model to create a chronological display of the visual, spatial, and verbal information. The episodic buffer relates the patient’s previous experiences, both personal and medical, to oral health. The recording of a comprehensive patient history is needed to accomplish this.

PHONOLOGICAL LOOP

Patients can more easily process information in each of the components of working memory, but especially the phonological loop, if there is a common script that is frequently repeated. A uniform delivery can help all team members convey to patients a common message, which aids in repetition and reinforces the message. Dental hygienists should be responsible for creating a script from which the dentist can revise. The script should be based on the culture of the dental practice, and specify how treatment will benefit the patient’s oral health. Partners of the practice, such as the periodontist and his or her team, can also help. Start by setting up a lunch meeting with the periodontist and his or her dental hygiene team, during which they may help compose hygiene guidelines and scripting. It is important that both general and specialist offices share a common philosophy. For instance, team members need to agree on when a patient should be referred to the periodontist, when laser therapy is appropriate, when chemotherapeutics or systemic antibiotics should be added as an adjunct to periodontal therapy, and when hygiene maintenance intervals should be adjusted.

VISUOSPATIAL SKETCHPAD

An estimated 65% of Americans are visual learners, while only 30% are auditory learners.19 Clinicians can use this fact to their advantage by utilizing digital radiography and photography. Digital radiography enables the clinician to highlight crown margins, caries lesions, and bone defects related to periodontitis, which can be magnified for patients to more easily view. Images are conveyed into greater reality for patients. Additionally, confirmation of radiographic calculus as seen through dental X-rays may also persuade patients to pursue periodontal therapy.

As a method of communication, visuospatial information allows patients to see (and appreciate) their condition through the eyes of the clinician. Visual aids, such as dental models and illustrated pamphlets, can be used as prompts for dentists and dental hygienists to motivate patients. Any literature given to the patient, such as information pamphlets, can be brought home and reviewed with the patient’s family. A plaque-disclosing solution should be used in conjunction with intraoral camera imaging. These tools reveal the areas missed during routine self-care, highlighting areas of the mouth in which the patient should focus. Disclosing solution is an underutilized tool for visual evidence of sight-specific hygiene deficiency. It is a conversation aid to help motivate patients to use specific hygiene aids or brushing techniques recommended by the dental team.

Technology in the dental practice should be embraced. Lasers, glycine powder-based air polishers, oral antioxidants, and chemotherapeutics have a variety of benefits to offer. When patients can feel the difference, they will become motivated to maintain the results. Additionally, the inherent benefits of technology may set the practice apart; practices that have adopted advanced, proven therapies give patients the confidence that their oral health professional is using everything in his or her power to treat the disease. Patients then recognize it is now their turn to maintain a healthy change.

After each maintenance appointment, clinicians should fax or email patient updates to the partnering periodontist. As co-therapists, periodontists and general dentists should communicate any changes in the patient’s restorative and periodontal status. Such an update may include new patient concerns, as well as documentation of hypersensitive teeth, self-care regimen recommendations, and new areas to watch. Update letters are invaluable tools to reinforce the relationship between general practitioners and specialists. When offices communicate changes in a patient’s status, it strengthens their collective goal of preserving his or her oral health. Patients build the impression that both offices keep a tight collaborative relationship to ensure the best possible care.

When the clinician incorporates working memory skills into the Health Belief Model, patients may be influenced to change their behavior. The benefits of implementing new behavior must outweigh the consequences of disease. The Health Belief Model indicates that patients will own their disease when they perceive susceptibility and severity, recognize barriers to improve their health, and understand the positive benefits of changing their behavior.20 This is why people with diabetes check their blood sugar, patients with hypertension avoid salt, and most individuals brush their teeth.

PUTTING IT INTO PRACTICE

The ISBM depends on the development of a network of professionals, including the primary dental team, the periodontal specialist’s team, physicians, and other specialists. Dental hygienists can set the precedence for the type of communication expected of the network. Each patient visit should be personalized. Understanding the patient should start with listening through the power of emotional intelligence.21

While following the guidelines discussed in this article is a good strategy for motivating patients to change their behavior, there will still be some who struggle. Often, the inability of patients to change is rooted in the manner in which the message was communicated. Messaging may be altered through the use of various aids in each of the working memory components, tailored to the patient for thorough understanding. The bottom line is that oral health professionals should not “give up” on noncompliant patients. Fenol and Mathew22 found that 34.6% of noncompliant patients were not adequately motivated by the practitioner. The surveyed patients acknowledged they did not receive enough information about the consequence of inaction and available therapies. Their report further acknowledged that if patients were made to understand their disease, acceptance and compliance would increase.

Implementing the ISBM is a team effort that starts with personal interactions. For instance, the dental hygienist wants to convey the meaning of probing depths and their relation to periodontal diseases. The clinician verbally explains the meaning of probing numbers. Then, after calling out the numbers to the assistant while probing, specific areas of deep probing depths are described as radiographic defects on the digital radiograph with radiopaque calculus. Visual aids should be used to explain what the pocket means in terms of the presence of calculus and attachment loss. The use of each component of working memory, as described, is much more powerful than merely explaining to the patient that he or she has some pocketing in the back areas. Patients cannot be expected to comprehend the complexities of periodontal disease processes. That is why repetition, reinforcement, and utilizing all the components of working memory are preferred over a single occurrence of any one component. Dental hygienists are key leaders in the practice’s hygiene program. They should be the patient’s primary contact for periodontal recare. In addition, noncompliant patients should remain a focus of the practice, as these are patients of record and inherent sources of recare, networking, and revenue. The ISBM is a group effort—between dental team members, offices, specialists, and other health care providers. Maintaining close relationships and open communication between providers ensures improved compliance and optimal results in the delivery of patient care.

References

- Hujoel PP, Leroux BG, Selipsky H, White BA. Non-surgical periodontal therapy and tooth loss. A cohort study. J Periodontol. 2000;71:736–742.

- Becker W, Berg L, Becker BE. The long term evaluation of periodontal treatment and maintenance in 95 patients. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1984;4:54–71.

- Becker W, Becker BE, Berg L. Periodontal treatment without maintenance. A retrospective study in 44 patients. J Periodontol. 1984;55:505–509.

- Becker W, Berg L, Becker BE. Untreated periodontal disease: a longitudinal study. J Periodontol. 1979; 50:234–244.

- Wilson TG Jr, Glover ME, Schoen J, Baus C, Jacobs T. Compliance with maintenance therapy in a private periodontal practice. J Periodontol. 1984;55:468–473.

- Baddeley A. The episodic buffer: a new component of working memory? Trends Cogn Sci. 2000;4:417–423.

- Jin J, Sklar GE, Min Sen Oh V, Chuen Li S. Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: A review from the patient’s perspective. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4:269–286.

- Fardal O. Interviews and assessments of returning noncompliant periodontal maintenance patients. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:216–220.

- Haynes RB, Taylor DW, Sackett DL, Gibson ES, Bernholz CD, Mukherjee J. Can simple clinical measurements detect patient noncompliance? Hypertension. 1980;2:757–764.

- McLane CG, Zyzanski SJ, Flocke SA. Factors associated with medication noncompliance in rural elderly hypertensive patients. Am J Hypertens. 1995;8:206–209.

- Leventhal H, Diefenbach M, Leventhal E. Illness cognition: using commonsense to understand treatment adherence and affect cognitive interaction. Cognitive Psychology and Research. 1992;16(2):143–163.

- Bartlett EE, Grayson M, Barker R, Levine DM, Golden A, Libber S. The effects of physician communication skills on patient satisfaction: recall and adherence. J Chronic Dis. 1984;37:755–764.

- Umaki TM, Umaki MR, Cobb CM. The psychology of patient compliance: a focused review of the literature. J Periodontol. 2012;83:395–400.

- Claffey N, Loos B, Gantes B, Martin M, Heins P, Egelberg J. The relative effects of therapy and periodontal disease on loss of probing attachment after root debridement. J Clin Periodontol. 1988;15:163–169.

- Atkinson RC, Shiffrin RM. Human memory: a proposed system and its control processes. In: Spence KW, Spence JT, eds. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation: Advances in Research and Theory. New York: Academic Press; 1968:89–195.

- Baddeley A, Thomson N, Buhanan M. Word length and the structure of short-term memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1975;14(6):575–589.

- Bolton R. People Skills: How to Assert Yourself, Listen to Others, and Resolve Conflict. New York: Simon & Schuster Inc; 1979.

- Baddeley A, Gathercole S, Papagno C. The phonological loop as a language learning device. Psychol Rev. 1998;105:158–173.

- Mind Tools. Learning Styles: Understanding Your Learning Preference. Available at: www.mindtools.com/mnemlsty.html. Accessed September 9, 2013.

- Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the Health Belief Model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15:175–183.

- Goleman D. Working with Emotional Intelligence. New York: Bantam Books; 1998.

- Fenol A, Mathew S. Compliance to recall visits by patients with periodontitis—is the practitioner responsible? J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2010;14:106–108.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. October 2013;11(10):63–68.