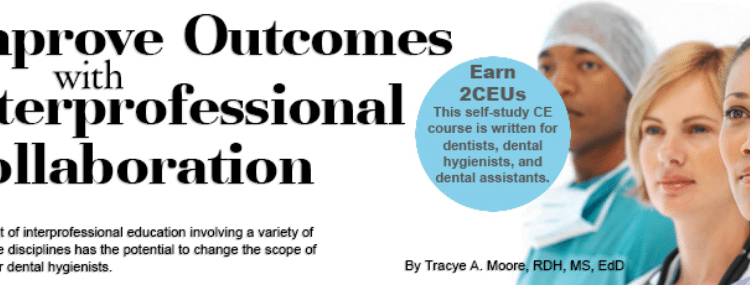

Improve Outcomes with Interprofessional Collaboration

The advent of interprofessional education involving a variety of health-care disciplines has the potential to change the scope of practice for dental hygienists.

<

This course was published in the August 2015 issue and expires August 31, 2018. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the components of interprofessional education and collaboration.

- Discuss the barriers to implementing interprofessional education.

- Identify the core competencies of interprofessional education.

- Provide examples of academic programs within dental hygiene and dentistry that are implementing interprofessional education.

Increased awareness among medical and dental providers regarding the connection between oral health, systemic disease, and overall health and wellness has given rise to an emphasis on interprofessional education and collaboration. Interprofessional teamwork, education, and collaborative practice are becoming key elements of efforts to promote health and treat patients.1 Interprofessional teamwork is defined as cooperation, coordination, and collaboration between health professions in delivering patient-centered care.2 Interprofessional education occurs when students or members of two or more health or social professions learn about, from, and with each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes.2–5 Interprofessional collaboration is when health professionals from different backgrounds provide comprehensive and coordinated services by working with patients, families, caregivers, and communities to deliver the highest quality of whole-body care across medical settings.2–5 Evidence suggests that interprofessional education enables effective collaborative practice, which in turn optimizes health care services, strengthens medical systems, and improves health outcomes.4 The interprofessional educational approach enables an interdisciplinary sharing of expertise, perspectives, and resources in a cooperative effort.2,3,5

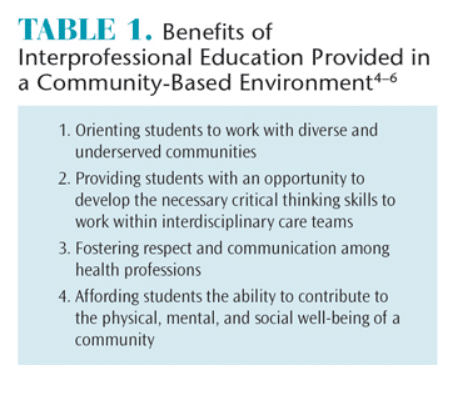

The report “Dental Education at the Crossroads” released by the Institute of Medicine in 1995 identified the need for dental professionals to engage with other health professionals for the benefit of their patients’ overall health.5 Interprofessional education provided in a community-based environment has many benefits (Table 1).4–6 Medical and dental academic program accreditation standards have further prompted the interprofessional movement, with the goal of graduating students who have a multidisciplinary approach to patient-centered care. The Commission on Dental Accreditation requires preparation of both dental and dental hygiene graduates for interprofessionalism.7

Recent federal health care legislation—the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act—contains drivers for interprofessional collaboration. These seek more efficient health care models that will bridge the medical-dental divide, thus improving patients’ access to care and achieving better health outcomes.8 The ACA strives to advance public health and reduce the per capita cost of health care via a “triple aim” approach.9 The triple aim in dentistry focuses on lower costs; evidence-based care, with an emphasis on risk assessment, management, and reduction; and the preservation of hard and soft tissue—all three facilitated by applying a medical care model to dentistry.10

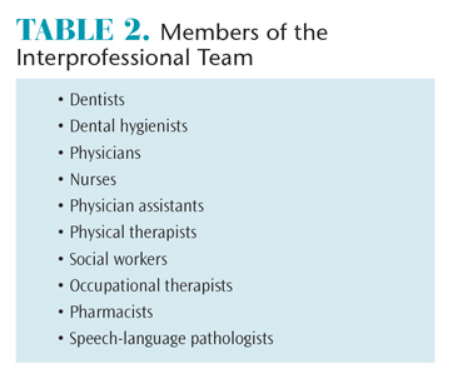

Today’s patients often have complex health needs with risk factors associated with other diseases that typically require an interdisciplinary approach.3,10 The collaboration of medical and dental teams may increase patient awareness about the oral heath connection to overall health and wellness, possibly alleviating secondary medical problems associated with poor oral health. Table 2 lists the participants in interprofessional teams.

BARRIERS TO IMPLEMENTATION

There are many challenges to implementing interprofessional education and collaboration, including the long-standing separate systems of dental and medical education, patient financing for dental care, crowded curricula, difficulty in training students and faculty, finding a location for training, scheduling conflicts, and lack of faculty development and administrative support.11–13 Because health profession education and training have traditionally been conducted through separate systems, physicians and other primary care practitioners are not trained to examine the oral cavity, screen for oral-systemic health issues, or provide preventive oral health education.11 Stand-alone dental schools also do not prepare dental students to participate in the comprehensive health care of patients.11 This separation contributes to oral health inequities across populations. Many employers provide basic medical health insurance but not dental benefits. Older adults covered by Medicare and economically disadvantaged individuals covered by Medicaid do not receive dental benefits. Private dental insurance operates under a different model than medical health insurance.11

Integrating interprofessional education into existing programs poses logistical issues related to the timing of semesters, curricula, and class scheduling.14 Many educational institutions house their medical and dental programs on different campuses.14 In addition, many stand-alone dental hygiene programs are not affiliated with medical or dental schools. It may be taxing for educational institutions to find time for training and a location to house multiple disciplines. Online training for students and faculty can be considered; however, face-to-face training or “hands-on” learning is most valuable in preparing students to interact with other health professionals.13 Faculty may also require training in interprofessional education if they have had little exposure to the concept. Many clinical sites where faculty members oversee training lack robust or explicit examples of interprofessional team-based care.13 Faculty training should be experiential and facilitated through interprofessional initiatives that are competency driven and in alignment with student competencies.13 It is also important to ensure the deans and department heads of different disciplines are supportive of interprofessional education.13

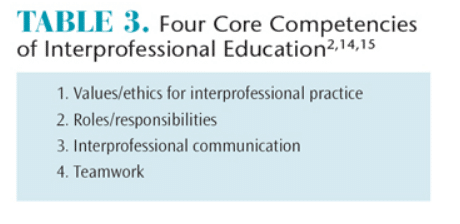

CORE COMPETENCIES

Table 3 lists the four core competencies of interprofessional education.2,14,15 Interprofessional values and ethics should be patient-centered with a community orientation and grounded in a sense of shared purpose to create safe and more effective systems of care. Students and faculty should work with individuals from other professions to maintain a climate of mutual respect and shared values.2,15 Learning interprofessional skills requires an understanding of how professional roles and responsibilities complement each other in patient-centered and community-oriented care. Students and faculty should use the knowledge of their roles and those of other professions to assess and address the health care needs of the patients and populations they serve.2,15 Communication competencies help students and faculty prepare for collaborative practice, and a readiness to work together initiates an effective interprofessional collaboration.2 Presenting information that team members, patients, families, and communities can understand contributes to the maintenance of health and the treatment of disease.2,15

Teamwork behaviors involve cooperating in patient-centered delivery of care; coordinating care with other health professionals so that gaps, redundancies, and errors are avoided; and collaborating with others through shared problem-solving and decision making.2 Working in teams involves sharing expertise and relinquishing some professional autonomy to work closely with others—including patients and communities—to achieve better outcomes.2 Shared accountability, problem solving, and decision making are characteristics of collaborative teamwork. Team members establish a common goal, synthesize their observations and profession-specific expertise, and collaborate and communicate as a team. Joint decision making is valued, and each team member is empowered to assume leadership on patient care issues appropriate to his or her expertise.2,15,16

APPLICATION IN DENTAL HYGIENE AND DENTISTRY

Academic health center schools, as well as other health profession programs are being encouraged to introduce joint learning experiences into their educational programs, so that students will graduate with an understanding of the roles and responsibilities of related health professions and how collaboration can lead to improved care.15 As learning shifts from the classroom to clinical practice, interprofessional work takes on a greater significance. Learning becomes more relationship-based and involves increasingly more complex interactions with others, including patients, families, and communities.1 Interprofessional education may be formal or informal at any point across the education-to-clinical practice continuum. Organized, formal interprofessional education activities provide the basic foundation of collaborative competence. They generally are didactic or simulated and occur in highly supervised clinical environments.1

The current interprofessional education literature is predominantly centered on dental, nursing, physician assistant, and podiatry students. In 2004, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science in Chicago designed a 1-credit pass/fail course with three components: didactic, service learning, and clinical to facilitate interprofessional education.3 The interdisciplinary family health course at the University of Florida in Gainesville has been providing interprofessional community-based learning experiences for more than 10 years.3 This course is required for all first-year students in the medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, nursing, physical therapy, psychology, and nutrition programs. The course is two semesters and is based on four home visits by an interprofessional team of three students with volunteer families in the local community.3

In 1997, the University of Washington in Seattle established the Center for Health Sciences Interprofessional Education in an effort to integrate teaching, research, and professional activities of the schools of medicine, pharmacy, nursing, social work, public health, and dentistry. More than 50 collaborative interprofessional offerings are available.

In 2005, the New York University (NYU) College of Nursing moved into the NYU College of Dentistry. Since then, the College of Nursing has established a nurse faculty practice in the dental school, in which nurse practitioners are available for consultation on the dental clinic floor.17 Twice weekly, nursing faculty work with dental students as they chart medical histories, educating them about conditions that might impact dental treatment.17 Since 2009, students in dentistry, osteopathic medicine, graduate nursing, physical therapy, and pharmacy at Western University in Pomona, California, have participated in the university’s interprofessional education curriculum, which is designed to progressively advance knowledge and skills through didactic instruction, simulation, and clinical care.16 Students are trained to provide outreach, triage, and patient care to at-risk populations.

A partnership between the University of the Pacific Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry and the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine was established in 2014.18 The two schools recently signed a memorandum of understanding for an interprofessional education program that will provide collaborative learning opportunities between fourth-year UCSF medical students and third-year dental students from the University of the Pacific. The medical students observe oral health care delivery for patients who have moderate to severe medical, developmental, and psychosocial conditions.18

The interprofessional education model at the Louisiana State University (LSU) Health Sciences Center School of Dentistry in New Orleans was developed in 2005. Dental hygiene students work with elementary school nurses in a school-based environment and perform noninvasive oral health screenings for children. Based on collaboration between LSU nursing students and dental hygiene students, the School of Dentistry curriculum now requires residents in advanced dentistry and dental hygiene students to work together as teams. These teams coordinate treatment with the directors of nursing in state developmental centers for people with neurodevelopmental/intellectual disability to increase their clinical competency and experience.19

The oral-systemic connection and interprofessional collaboration are among some of dental education’s key focus areas in the Mesa Community College (MCC) dental hygiene program in Arizona. In 2015, Prendergast et al20 developed the Bedside Oral Exam (BOE) to determine the oral health risks of patients in hospital settings.20 MCC dental hygiene students perform BOEs in pairs under the supervision of hospital staff and faculty. Future plans for this collaboration include dental hygiene students educating other health professionals on the effects of pathogenic oral bacteria on systemic health and the benefits of preventive oral care.20

Northern Arizona University (NAU) in Flagstaff instituted a family health day in 2015 in which the family of students and faculty were invited to participate in hearing tests, blood pressure screenings, nutritional education, glucose screening, and dental hygiene services. Students from different disciplines worked together at the various stations. Students from all disciplines completed a three-question survey after the health fair ended. Most students commented they learned something new from a different discipline, such as how to communicate with students in other programs of study, how to educate families on the importance of health and dental screenings, and how to work in teams. Due to inadequate training of some students prior to the event, however, many felt they did not know how to integrate their particular area of study with other departments while assigned to different stations. Sufficient training of students and faculty prior to the next family health fair will be prioritized to facilitate more efficient and effective education of the community that NAU serves.

CONCLUSION

Oral health professionals can play a major role in medical screening and monitoring of chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension. Research has demonstrated that the status of patients’ diabetes and hypertension can affect both their oral and overall health.15,21 The interprofessional education/collaboration model expands the dental hygienist’s scope of practice to include disease assessment and prevention, chronic disease screening, disease management within an integrated health care system, and managing, communicating, and collaborating with other health professionals.21,22 Administrative leadership, funding, and support from within the academic setting are critical to engage all disciplines. Faculty need to be adequately trained in order to teach students how to ensure high-quality outcomes utilizing a multidisciplinary approach. Tomorrow’s dental hygienist will need to be adequately trained in interprofessionalism to meet the growing demands of a diverse population and provide cost-effective, efficient quality oral health care in a team-based atmosphere.

REFERENCES

- National Academy of Sciences. Measuring the Impact of Interprofessional Education on Collaborative Practice and Patient Outcomes, 2015. Available at: nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=21726. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- Interprofessional Collaborative Practice. Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: Report of an Expert Panel. Available at: aacn.nche.edu/education-resources/ipecreport.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- Bridges DR, Davidson RA, Odegard PS, Maki IV, Tomkowiak J. Interprofessional collaboration: three best practice models of interprofessional education. Med Educ Online. 2011;8:16.

- World Health Organization, Department of Human Resources for Health. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education & Collaborative Practice. Available at:?who.int/hrh/resources/ framework_action/en. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- Hettinger L, Gwozdek A .Utilizing community-based education as a springboard for interprofessional collaboration. Access. 2015;11–13.

- Price SS, Funk AD, Shockey AK, et al. Promoting oral health as part of an interprofessional community-based women’s health event. J Dent Ed. 2014;78:1294–1300.

- Commission on Dental Accreditation. Accreditation Standards for Dental Hygiene Programs. Available at:?ada.org/~/media/ coda/files/dh.ashx. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- Edelstein BL. The roles of federal legislation and evolving health care systems in promoting medical-dental collaboration. Calif Dent Assoc J. 2014;42:19–23.

- Robinson LA, Krol DM. Interprofessional education and practice…moving toward collaborative, patient-centered care: part two. Calif Dent Assoc J. 2014;42:617–618.

- Krol DM, Gesko D, Hilton I, Garlan T, McCauley L. Panel proceedings; conference on interprofessional education and practice. California Dental Association and American Dental Education Association. February 2014. Calif Dent Assoc J. 2014;42:622–623.

- Mouradian WE, Lewis CW, Berg JH. Integration of dentistry and medicine and the dentist of the future: the need for the health care team. Calif Dent Assoc J. 2014;42:687–695.

- Conway SE, Smith WJ, Truong TH, Shadid J. Interprofessional pharmacy observation activity for third-year dental students. J Dent Ed. 2014;78:1313–1318.

- Hall LW, Zierler BK. Interprofessional Education and Practice Guide No. 1: developing faculty to effectively facilitate interprofessional education. J Interprof Care. 2015:29:3–7.

- Valachovic RW. Integrating oral and overall health care-on the road to interprofessional practice: building a foundation for interprofessional education and practice. Calif Dent Assoc J. 2014;42:25–27.

- Formicola AJ, Andrieu SC, Buchananan JA, et al. Interprofessional education in US and Canadian dental schools: an ADEA tam study group report. J Dent Ed. 2012;76:1250–1268.

- Friedrichsen S, Martinez TS, Hostetler J, Tang JMW. Innovations in interprofessional education: building collaborative practice skills. Calif Dent Assoc J. 2014;42:627–635.

- Wilder RS. Dental hygienists and interprofessional collaboration: thoughts from 1927. J Den Hyg. 2013;87:108–109.

- University of Pacific Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry. Pacific Dugoni Partners with UCSF School of Medicine on Interprofessional Education Opportunities. Available at: dental.pacific.edu/ News_and_Events/News_Archive/Pacific_Dugoni_Partners_with_UCSF_School_of_Medicine_on_Interprofessional_Education_Opportunities.html. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- Mabry CC, Mosca NG. Interprofessional educational partnerships in school health for children with special oral health needs. J Den Ed. 2006;70:844–850.

- Prendergast V, Kleiman C, King M. The Bedside Oral Exam and the Barrow Oral Care Protocol: translating evidence-based oral care into practice. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2013;29:282–290.

- Robinson L. Interprofessional education and practice….the dentist of the future: part three. Calif Dent Assoc J. 2014;42:685–686.

- Berg JH, Mouradian WE. Integration of dentistry and medicine and the dentist of the future: changes in dental education. Calif Dent Assoc J. 2014;42:697–700.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. August 2015;13(8):28–31.