Addressing White Spot Lesions

Determining the cause of these lesions is essential to successful treatment and esthetic improvement.

This course was published in the August 2015 issue and expires August 31, 2018. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVE

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Explain how to make a differential diagnosis between various types of white spot lesions.

- List different treatment modalities for white spot lesions.

- Discuss the esthetic considerations when addressing white spot lesions.

White spot lesions, however, are not only the result of demineralization. Fluorosis, hypomineralization/hypomaturation, and hypoplasia can also cause these lesions. Dental professionals are charged with performing a differential diagnosis to determine the etiology of white spot lesions, as well as providing appropriate treatment planning and esthetic management of the lesions that will meet patient expectations.

While fluoride remains an important factor in the prevention and management of dental caries, widespread exposure from different sources has increased the risk of fluorosis in communities with and without fluoridated drinking water.3 Unlike early caries lesions, dental fluorosis is a developmental disturbance caused by exposure to high concentrations of fluoride during tooth development, which leads to enamel with lower mineral content and increased porosity.4 Fluorosis may present initially as white spot lesions that then progress to brown spots due to the inherent porosity that makes them more susceptible to stain.

Another form of developmental enamel anomaly that results in discoloration is associated with genetic defects and environmental insults such as metabolic conditions and exposure to drugs, chemicals, radiation, and trauma.5 These defects are associated with hypoplasia, hypomineralization, or hypomaturation. Enamel hypoplasia occurs if the matrix formation is affected and results in pits or grooves, or thin and missing enamel. Hypomineralization is due to maturation disturbance, which results in reduced mineralization and commonly presents as soft enamel. Hypomaturation is caused by a reduction in the deposition of minerals at the end stage of mineralization and is characterized by altered translucency affecting the entire tooth, or, in a localized area, it presents as an opacity.6

Considering the wide variety of etiology of white spot lesions, it is imperative to establish a proper diagnosis, which is based on a thorough review of dental and medical history and clinical examination evaluating the location, symmetry, outline form, depth, and opacity of the lesion.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis is essential to the successful treatment of white spot lesions. First, basic information is gathered about the patient’s medical and dental history, including neonatal or early childhood illness, use of drugs and medications, and past infections or trauma related to primary teeth.7

Fluoride exposure is another important factor in the diagnosis. Patients should be asked whether they reside in a community with water fluoridation, their child’s history of fluoride supplementation, amount of toothpaste used, and history of swallowing toothpaste in childhood.7 While the criteria for dental fluorosis is clear, there are circumstances where a final diagnosis may be challenging. Additionally, individual caries risk assessments should be performed so the most appropriate intervention can be implemented before permanent damage is done to tooth structure.

Descriptive clinical presentation of the lesion is another important guide for the diagnostic process. Several classifications and indices are used: Al-Alousi Index,8 Developmental Defects of Enamel Index (DDE),9 and Modified DDE Index.6 According to the Modified DDE Index, developmental defects are differentiated based on three broad visual clinical categories: demarcated opacities, diffuse opacities, and hypoplasia. The extent of the defect is also considered. When selecting treatment options, however, lesion depth is another critical component that can be estimated with the aid of a transilluminator. The transilluminator is positioned on the lingual surface to examine the lesion depth, as a darker color indicates deeper staining (Figure 1).

Demineralization and white spots associated with early noncavitated lesions can be observed on smooth surfaces of teeth along the gingiva and interproximal areas. Based on the International Caries Detection and Assessment System, if no lesion is apparent on a smooth surface when the tooth is wet, but a noncavitated lesion appears once the tooth is adequately dried, the lesion is classified as a code 1. If a noncavitated lesion is apparent both when the tooth is wet and dry, it is classified as a code 2.10 The outline is usually well-defined, following the contour of the gingival tissue. Upon identification of demineralization, it is important to assess the lesion activity to properly plan for management. Predictors of an active lesion include: located in a plaque stagnation area, white in color, dull appearance, and presence of rough surface or surface breakdown. Predictors of an inactive or arrested lesion include: located in a nonplaque stagnation area (above the gingival margin), brown in color, shiny appearance, and intact, smooth, and hard surface.11

Dental fluorosis commonly occurs bilaterally and presents with a thin, diffuse, and lattice-type opacity corresponding to perikymata (ridges on the surface of enamel) running across the tooth surface to an entirely chalky white overall tooth surface.12 The lesion can be localized to a few teeth or can include the full dentition. The lesion’s depth can vary from superficial to deep penetration into the enamel based on the severity of the fluorosis.

Hypomineralization and hypomaturation lesions present with well demarcated margins, usually affecting one or several teeth with a symmetrical distribution.9 Hypoplasia is characterized by diffuse opacities of white and yellow discoloration, often accompanied with pitting and loss of enamel structure. Slightly different clinical representations of white spot lesions may occur simultaneously.

LESION MANAGEMENT

Minimal intervention is ideal for the management of white spot lesions and should start with remineralization approaches to arrest the disease process and restore enamel strength and function. The patient’s expectations are vital to the decision-making process, as esthetic concerns should be addressed concurrently. No treatment may also be an option.

Ideally, demineralization should be prevented by reducing the frequency of fermentable carbohydrate consumption, decreasing the number of cariogenic bacteria present, and increasing salivary flow. Best evidence for remineralization is the topical use of fluoride based on the patient’s caries risk assessment. In a high-risk patient, a prescription 5,000 ppm fluoride dentifrice may be recommended, in addition to the application of in-office 2.26% fluoride varnish.13 Silver diamine fluoride has recently become available in the United States. Application of this liquid can arrest active dentinal and enamel caries, preventing further disease progression.14,15 However, silver diamine fluoride stains the lesions that it arrests, so its use on permanent anterior teeth may be contraindicated. Calcium phosphate technologies, including amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP); casein phosphopeptide-ACP, or Recaldent®; calcium sodium phosphosilicate, or NovaMin®; and tricalcium phosphate, are also available, though additional research is needed to support their use.11

FIGURE 2B. This is a post-whitening view of the lesions in Figure 2A, demonstrating a blending in of the white spot lesions. COURTESY OF MARCOS VARGAS, BDB, DDS, MS

FIGURE 2B. This is a post-whitening view of the lesions in Figure 2A, demonstrating a blending in of the white spot lesions. COURTESY OF MARCOS VARGAS, BDB, DDS, MS

ESTHETIC CONCERNS

If a white spot lesion is an esthetic concern, tooth whitening should first be considered in the effort to blend the lesion into the natural dentition. Tooth whitening involves diffusion of the whitening material into the enamel and dentin to interact with stain molecules. It also creates micro-morphologic alterations on the tooth surface that affect its optical properties.16 When properly monitored by a dental professional, tooth whitening is safe and effective in improving the appearance and color of teeth.17

Tooth whitening with hydrogen peroxide or carbamide peroxide can be broadly classified into three main categories: dentist-supervised in-office whitening; dentist-dispensed, patient-applied at-home whitening; and over-the counter whitening. Dentist-supervised whitening is performed in the office with highly concentrated materials of up to 40% hydrogen peroxide and is frequently combined with light activating devices. Dentist-dispensed patient-applied at-home whitening uses custom fabricated trays and a wide range of carbamide peroxide gels (7% to 22%). Over-the-counter whitening products are available in strips, paint-on gels, or brush-on adhesive liquids. Current research on the efficacy of in-office whitening vs at-home whitening shows that both techniques provide satisfactory outcomes without significant adverse effects in terms of tooth and gingival sensitivity.18

FIGURE 3B. This post-treatment view shows the teeth in Figure 3A after whitening and microabrasion have been completed.

FIGURE 3B. This post-treatment view shows the teeth in Figure 3A after whitening and microabrasion have been completed.

In many instances, whitening will lighten the tooth color so that the white spot lesion naturally blends in (Figure 2A and Figure 2B). Upon completion of the whitening process, patients can decide if further treatment, such as minimally invasive restorative procedures, is needed to meet their esthetic expectations.

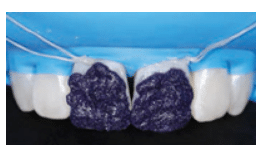

Enamel microabrasion is indicated for intrinsic discoloration or texture alteration due to enamel hypoplasia, amelogenesis imperfecta, or fluorosis.19 It involves a combination of erosion and abrasion of the superficial enamel by a low concentration of hydrochloric acid in conjunction with mechanical rubbing of abrasive silicon carbide particles in a water-soluble mixture.20 The success of microabrasion is related to proper case selection and the performance of a highly precise procedure. Microabrasion is used for superficial defects and is contraindicated in lesions with dentin involvement and deeper opaque stains associated with severe hypoplasia, which may require a restorative approach.21 When overall tooth color change is desired, microabrasion can be preceded or followed by tooth whitening to improve the overall esthetic outcome (Figure 3A and Figure 3B). Proper isolation with a rubber dam is necessary during microabrasion procedures to ensure patient safety. Furthermore, periodic evaluation of the enamel thickness labio-lingually with a mouth mirror is helpful in assessing the amount of enamel removed during the procedure (Figure 4A through Figure 4E). Upon completion of microabrasion, fluoridated prophylaxis paste should be applied to aid in remineralization of the treated surface.

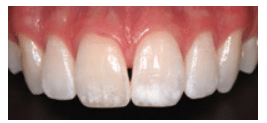

FIGURE 4A. Localized white spot lesions caused by fluorosis affect the incisal thirds of central incisors.

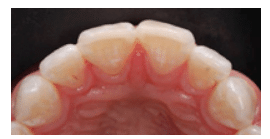

FIGURE 4B. This post-whitening view of the teeth in Figure 4A demonstrates the still evident white spots, which prompted the patient to ask for additional esthetic treatment.

FIGURE 4B. This post-whitening view of the teeth in Figure 4A demonstrates the still evident white spots, which prompted the patient to ask for additional esthetic treatment.

FIGURE 4D. The periodic evaluation of the enamel thickness labio-lingually with the aid of a mouth mirror is recommended to avoid excessive removal of enamel.

FIGURE 4D. The periodic evaluation of the enamel thickness labio-lingually with the aid of a mouth mirror is recommended to avoid excessive removal of enamel.

Resin infiltration with a low viscous, hydrophilic resin material in the porous lesion has been proposed as an innovative treatment for white spot lesions.22 Upon infiltration of the matrix into the lesion, further demineralization can be inhibited. An additional benefit is that the refractive index of the lesion is altered to make it closely comparable to that of the natural tooth, thereby enhancing esthetics.

Resin infiltration consists of 15% hydrochloric acid with a proprietary resin infiltrate. After isolation, the white spot lesion is acid etched with 15% hydrochloric acid for 2 minutes, followed by rinsing and drying with ethanol. The last step involves the application of the resin infiltrate that is then light-cured. Due to the recent introduction of this technique, long-term results on the efficacy and stability of resin infiltration for the treatment of white spot lesions are unavailable. A short-term clinical study found that the esthetic outcome with resin infiltration was satisfactory for the treatment of post-orthodontic white spots.23 A combination of microabrasion followed by resin infiltration can also be used to improve the esthetic outcome of white spot lesions (Figure 5A and 5B).

FIGURE 5A. An unesthetic white spot lesion is located on the upper central incisors. COURTESY OF MARCOS VARGAS, BDB, DDS, MS

FIGURE 5B. This is a post-treatment view of the teeth from Figure 5A after microabrasion and resin infiltration have been performed. COURTESY OF MARCOS VARGAS, BDB, DDS, MS

FIGURE 5B. This is a post-treatment view of the teeth from Figure 5A after microabrasion and resin infiltration have been performed. COURTESY OF MARCOS VARGAS, BDB, DDS, MS

Restorative approaches with direct resin composites are indicated when conservative treatment approaches, such as remineralization, tooth whitening, microabrasion, and resin infiltration, are unsuccessful in removing or masking the white spot lesion. This is often seen in deeper lesions associated with enamel hypoplasia, in which the lesion has to be removed and the lost tooth structure replaced with a composite resin restoration.7

CONCLUSION

White spot lesions of different etiology can cause functional and esthetic concerns that need to be managed properly to meet patients’ expectations. Careful review of medical and dental history and a detailed clinical examination will aid in the differential diagnosis of superficial white spot lesions. Treatment planning and management should emphasize a proper sequencing, starting with the most conservative treatment option. The patient should also be part of the decision-making process from start to finish.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to thank Marcos Vargas, BDB, DDS, MS; Marcela Hernandez, DDS, MS; and Justine Kolker, DDS, MS, PhD, for their help with this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Cochrane NJ, Cai F, Huq NL, Burrow MF, Reynolds EC. New approaches to enhanced remineralization of tooth enamel. J Dent Res. 2010;89:1187–1197.

- Mizrahi E. Enamel demineralization following orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod. 1982;82:62–67.

- Iida H, Kumar JV. The association between enamel fluorosis and dental caries in US schoolchildren. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:855–862.

- Abanto Alvarez J, Rezende KM, et al. Dental fluorosis: exposure, prevention and management. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14:103–107.

- Seow WK. Developmental defects of enamel and dentin: challenges for basic science research and clinical management. Aust Dent J. 2014;59:143–154.

- Clarkson J. Review of terminology, classification, and indices of developmental defects of enamel. Adv Dent Res. 1989;3:104–109.

- Wray A, Welbury R. UK National Clinical Guidelines in Paediatric Dentistry: Treatment of intrinsic discoloration in permanent anterior teeth in children and adolescents. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2001;11:309–315.

- . Al-Alousi W, Jackson D, Compton G, Jenkins OC. Enamel mottling in a fluoride and in a non-fluoride community. Br Dent J. 1975;138:56–60.

- An epidemiological index of developmental defects of dental enamel (DDE Index). Commission on Oral Health, Research and Epidemiology. Int Dent J. 1982;32:159–167.

- ICDAS II—International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS II) Criteria Manual. Available at: icdas.org/uploads/ICDAS%20Criteria %20Manual%20Revised%202009_2.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2015.

- Kwon SR, Kolker J. Implement a minimally invasive approach. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2014;12(8):22–25.

- Fejerskov O, Kidd E. Dental Caries—The Disease and its Clinical Management. 2nd ed. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008.

- American Dental Association Guide: topical fluoride for caries prevention: executive summary of the updated clinical recommendations and supporting systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:1279–1291.

- Peng JJ, Botelho MG, Matinlinna JP. Silver compounds used in dentistry for caries management: a review. J Dent. 2012;40:531–541.

- Beltrán-Aguilar ED. Silver diamine fluoride (SDF) may be better than fluoride varnish and no treatment in arresting and preventing cavitated carious lesions. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2010;10:122–124.

- Kwon SR, Wertz PW. Review of the mechanism of tooth whitening. J Esthet Restor Dent. May 13, 2015. Epub ahead of print.

- American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. Tooth Whitening/Bleaching: Treatment Considerations for Dentists and Their Patients. Chicago: American Dental Association; 2009.

- Auschill TM, Hellwig E, Schmidale S, Sculean A, Arweiler NB. Efficacy, side-effects and patients’ acceptance of different bleaching techniques (OTC, in-office, at-home). Oper Dent. 2005;30:156–163.

- Sunfeld RH, Croll TP, Briso AL, de Alexandre RS, Sundfeld Neto D. Considerations about enamel microabrasion after 18 years. Am J Dent. 2007;20:67–72.

- Croll TP, Helpin ML. Enamel microabrasion: a new approach. J Esthet Dent. 2000;12:64–71.

- Reston EG, Corba DV, Ruschel K, Tovo MF, Barbosa AN. Conservative approach for esthetic treatment of enamel hypoplasia. Oper Dent. 2011;36:340–343.

- Paris S, Meyer-Lueckel H. Inhibition of caries progression by resin infiltration in situ. Caries Res. 2010;44:47–54.

- Knösel M, Eckstein A, Helms HJ. Durability of esthetic improvement following Icon resin infiltration of multibracket-induced white spot lesions compared with no therapy over 6 months: a single-center, split-mouth, randomized clinical trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2013;144:86–96.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. August 2015;13(8):32–35.