SVETIKD/E+/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

SVETIKD/E+/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Essentials of Operatory Preparation, Disinfection, and Sterilization

Oral health professionals must adhere to evidence-based guidelines to ensure the dental operatory is safe for both patients and clinicians.

Professionals and researchers in dentistry, medicine, and public health continue to discover more effective and innovative ways to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2 that causes COVID-19. In dental settings, operatory preparation and disinfection are essential to providing safe patient care. Adequate hand hygiene; proper use of personal protective equipment (PPE); and thoroughly disinfecting environmental surfaces, devices, and equipment are among the most important facets of basic infection control.1–3 Hand hygiene (eg, handwashing or hand sanitizing) is one of the most critical measures for reducing the risk of transmitting organisms to patients and oral health professionals, as it substantially reduces pathogens when performed properly.2,3 Meticulous planning for disinfection and sterilization of all aspects of the dental office, operatory, and equipment is essential for providing safe patient care. As the science related to COVID-19 remains fluid, oral health professionals will need to consistently seek updates on evidence-based guidelines and protocols.

STANDARDS AND PROTOCOLS

Not all states require infection control continuing education for dental personnel, therefore, each oral health professional must strive to implement recommendations that represent current evidence and best practices. The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides guidance on infection control protocols in the dental setting, specifically the 2003 CDC Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings, while the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) is a regulatory agency responsible for enforcing standards. Dental practices are obligated to comply with OSHA’s Bloodborne Pathogens (BBP) Standard (29 CFR 1910.1030) and Hazard Communication Standard (29 CFR 1910.1200).4–6

Because oral health professionals are routinely exposed to blood and other potentially infectious materials (OPIM), OSHA requires employers to instill measures to protect clinicians from such exposure via the provision of PPE, including gloves, masks, protective eyewear, and protective garments; inoculation against hepatitis B; provision of safe work practices, such as safety devices (sharps containers and needle recapping devices); and infection control training at least once per year.4,6

OSHA also stipulates that employers provide training and PPE for employees who handle chemicals.3 Many types of chemicals are used in the dental setting, including surface disinfectants, cleaning and housekeeping agents, and dental materials. Safety data sheets must accompany all chemicals and contain information about safe handling, including methods for storage, disposal, and first aid instructions in the event of accidental exposure. Current safety data sheet information must be kept for every chemical used and be accessible for at-risk employees at all times.3

Noncompliance with any of these regulations may result in OSHA violations.7

OPERATORY SURFACES

The CDC separates operatory surfaces into two categories: clinical contact surfaces (CCS) and housekeeping surfaces. CCS can be directly contaminated either by patients’ fluid particles or contact with oral health professionals’ contaminated gloves. Housekeeping surfaces generally do not contact patient material or pose a lower risk for disease transmission (floors, walls, window, sinks, etc).

The potential for direct patient contact determines the protocols for cleaning and disinfecting surfaces. Other considerations are frequency of hand contact and probable contamination of the surface or area with body fluids or environmental sources of microorganisms (soil, dust, or water).2,3

Frequently touched surfaces can serve as reservoirs for microbial contamination (eg, light handles, switches, drawer knobs, chair controls, etc). As such, barrier protection and/or disinfection of environmental surfaces must be performed prior to and between each patient to minimize the risk of disease transmission and healthcare–associated infections.2,3 Automated controls for soap dispensers, water faucets, and towel dispensers are a convenient way to minimize contamination of frequently touched surfaces.

All items not essential to patient care should be removed from counters such as supply containers, pamphlets, personal items, etc. Disposable items and unit doses should be used whenever possible. Barriers should be implemented for areas and items that are difficult to clean.2,3 The dental operatory contains many items that are difficult to disinfect including irregular surfaces, buttons, switches, electronics, and keyboards. The decision to implement barriers and/or disinfection should be based on evidence-based guidelines and must consider available manpower, cost, and efficiency. Manufacturer-recommended, custom-fit barriers should be used for intraoral cameras, curing lights, lasers, and X-ray sensors that cannot be sterilized but are used intraorally.

All CCS should be cleaned and disinfected at the beginning of the day, between patients, and at the end of the day using a US Environmental Protection Agency-(EPA) registered hospital or intermediate-level disinfectant that remains wet for the recommended contact time.2,3,8 Housekeeping surfaces (eg floors, walls, and sinks) do not pose a significant risk for disease transmission in dental healthcare settings; however, floors and sinks should be cleaned on a daily basis, and spills cleaned up immediately. An EPA-registered low- or intermediate-level disinfectant or detergent designed for general housekeeping purposes should be used in patient-care areas.2,3,8 Per OSHA guidelines, puncture and chemical resistant gloves should be worn when using intermediate-level disinfectant.

The first step in the cleaning process is to remove any bioburden in order for disinfectant solutions to be effective within the recommended contact time. High ethyl alcohol solutions kill bacteria and deactivate viruses. The most commonly used disinfectants on the EPA’s list for effectively eliminating the novel coronavirus contain quaternary ammonium, sodium hypochlorite, hypochlorous acid, triethylene glycol and glycolic acid, hydrogen peroxide, chlorine dioxide, isopropanol, peroxyacetic acid, phenolic, ethanol, citric acid, sodium carbonate peroxyhydrate, and/or thymol.2,3,9

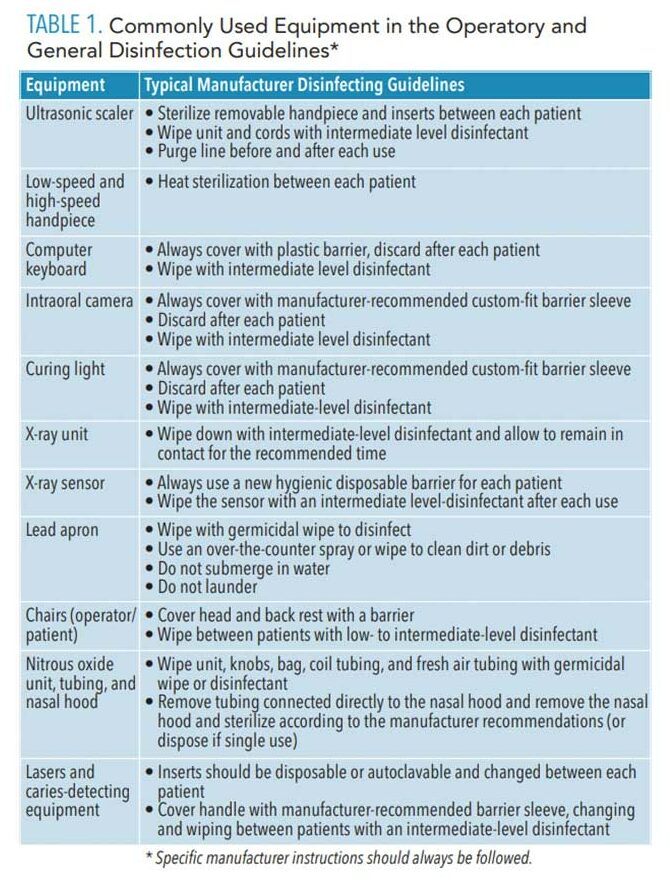

EQUIPMENT

Manufacturer’s information for use should be reviewed to determine the appropriate method and products for the disinfection of dental equipment. Some equipment is sensitive to chemicals; therefore, products should be carefully selected for specific equipment and uses. Table 1 lists the most common equipment found in an operatory and general disinfection guidelines.10–12

As SARS-CoV-2 lingers in the air, it may be wise to wait before disinfecting patient rooms. However, the CDC does not currently recommend a specific wait time. In June 2020, the American Dental Association (ADA) advised oral health professionals to allow some time before disinfecting the operatory.13 Considerations include air flow and filtration rates, number and length of aerosol-generating procedures, patient volume, and use of rubber dams.13 Due to the potential for aerosols to linger, clinicians may consider donning PPE prior to entering the operatory and doffing PPE after they leave the operatory.

DENTAL AEROSOLS

Dental procedures produce aerosols, splatter, and droplets contaminated with microorganisms, saliva, and blood, which may provide a potential route for disease transmission. The creation of aerosols by rotary handpieces, ultrasonic devices, and air water syringes has become a major concern for the potential spread of viruses and microorganisms, including SARS-CoV-2. Until new inventions are available to prevent or capture aerosols, the spread of these potentially harmful aerosols must be minimized. The CDC’s current guidelines recommend avoiding aerosol-producing dental procedures, but when this is not possible, the following strategies should be implemented: preprocedural rinsing, high-volume evacuation (HVE), rubber dams, minimally invasive/atraumatic restorative techniques, hand scaling, and four-handed dentistry.11,12,14,15 An HVE tip measuring 8 mm or greater in diameter attached to an effective evacuation system can remove up to 100 cubic feet of air per minute.15

In addition to traditional HVE tips, many new HVE systems are available to reduce aerosols. OSHA requires employers to establish a respiratory program plan to protect employees from exposure to respiratory hazards. The respirator selected must be adequate to reduce the user’s exposure to aerosols, droplets, chemicals, and other hazards.16

Dental unit waterlines (DUWL) can play a role in the creation of contaminated aerosols. The most common dental unit water sources are municipal water and closed-bottle systems. Both require cleaning and disinfection. Without appropriate maintenance, microorganisms can adhere to the inner surface of waterlines and form a biofilm of organisms that can enter the water stream. Microbial contamination of waterlines pose the greatest risk for older adults and the immunocompromised.17 System design, flow rates, and equipment impact the microbiological quality of operatory water.2

Waterlines, including handpieces and ultrasonic scalers, should be run or flushed at the beginning of each day and between each patient for 20 seconds to 30 seconds even if anti-retraction valves are present.2,18 The EPA standard for safe drinking water and routine dental care is ≤ 500 CFU/mL but sterile saline or sterile water should be used for surgical procedures.2,14,17,18 The 2003 CDC guidelines recommend bacterial counts should be “as low as reasonably achievable” but must meet the EPA standard for safe drinking water.2

Multiple systems are available for cleaning and maintaining waterlines, including antimicrobial tablets (chemical treatments), filters, and anti-retraction valves to control microbial contaminates and biofilms. DUWLs should be tested regularly based on the specific system recommendations to maintain the established standards.2,17,18

AIRFLOW

Heating, ventilating, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems in a dental facility may disperse aerosol contaminants. COVID-19 has brought attention to the importance of a well-designed and maintained HVAC system to prevent the potential spread of viruses and microorganisms. Operatories should be oriented parallel to the direction of airflow when possible.14 Increasing outside air flow combined with the use of high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters that trap organisms in the HVAC system may improve indoor air quality. Some offices incorporate additional portable air filtration units with HEPA filters to further reduce airborne contamination in the operatory. Air exchange systems should be checked, measured, and monitored to determine if modifications are required. Alternative disinfection methods such as fogging, LED blue lights, and upper-room ultraviolet germicidal irradiation systems are used in medical and dental settings as adjuncts but additional research is needed to determine the effectiveness of these systems.14

CONCLUSION

Dental practices must use evidence-based guidelines and standards when developing and implementing infection control protocols. Patients trust oral health professionals to uphold the highest standards of infection control to ensure a safe environment. Informing patients of additional measures and precautions implemented in the office for their safety will increase confidence in receiving care.

REFERENCES

- Schneiderman MT, Cartee DL. Surface disinfection. In: DePaola L., Grant L, eds. Infection Control in the Dental Office. New York: Springer, Cham; 2019:169–191.

- Kohn WG, Harte JA, Malvitz DM, et al. Guidelines for infection control in dental health care settings—2003. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(RR-17):1–61.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary of Infection Prevention Practices in Dental Settings: Basic Expectations for Safe Care. Available at: cdc.g/v/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/pdf/safe-care2.pdf. Accessed February 21, 2021.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. OSHA Laws & Regulations. Available at: osha.gov/laws-regs/oshact/section5-duties. Accessed February 21, 2021.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Bloodborne Pathogens and Needlestick Prevention. Available at: osha.gov/bloodborne-pathogens. Accessed February 21, 2021.

- Garland K. Infection prevention post-exposure protocols. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2019;17(11):18–20.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. OSHA Penalties. Available at: osha.gov/penalties. Accessed February 21, 2021.

- US Environmental Protection Agency. List N: Disinfectants for Use Against SARS-CoV-2. Available at: epa.gov/pesticide-registration/list-n-disinfectants-use-against-sars-cov-2. Accessed February 21, 2021.

- US Environmental Protection Agency. List N Advanced Search Page: Disinfectants for Coronavirus (COVID-19). Available at: epa.gov/pesticide-registration/list-n-advanced-search-page-disinfectants-coronavirus-covid-19. Accessed February 21, 2021.

- Acosta-Gio E, Bednarsh H, Cuny E, Eklund K, Mills S, Risk D. Sterilization of dental handpieces. AJ J Infect Control. 2017;45:937–938.

- American Dental Association. Summary of ADA Guidance During the COVID-19 Crisis. Available at: success.ada.org/~/media/CPS/Files/COVID/COVID-_9_Int_Guidance_Summary.pdf. Accessed Accessed February 21, 2021.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. ADHA Interim Guidance on Returning to Work. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/ADHA_TaskForceReport.pdf. Accessed February 21, 2021.

- American Dental Association. ADA Responds to Change from CDC on Waiting Period Length. Available at: ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/2020-archive/june/ada-responds-to-change-from-cdc-on-waiting-period-length. Accessed February 21, 2021.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidance for Dental Settings. Interim Infection Prevention and Control Guidance for Dental Settings During the COVID-19 Response. Available at: cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/dental-settings.html. Accessed February 21, 2021.

- Harrel SK, Molinari J. Aerosols and splatter in dentistry, a brief review of the literature and infection control implications. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:429–437.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Respiratory Protection Program Guidelines. Available at: osha.gov/enforcement/directives/cpl-02-02-054. Accessed February 21, 2021.

- American Dental Association. Dental Unit Waterlines. Available at: ada.org/en/member-certer/oral-health-topics/dental-unit-waterlines. Accessed February 21, 2021.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Dental Unit Waterlines. Available at: fda.gov/medical-devices/dental-devices/dental-unit-waterlines. Accessed February 21, 2021.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2021;19(3):22–25.